Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

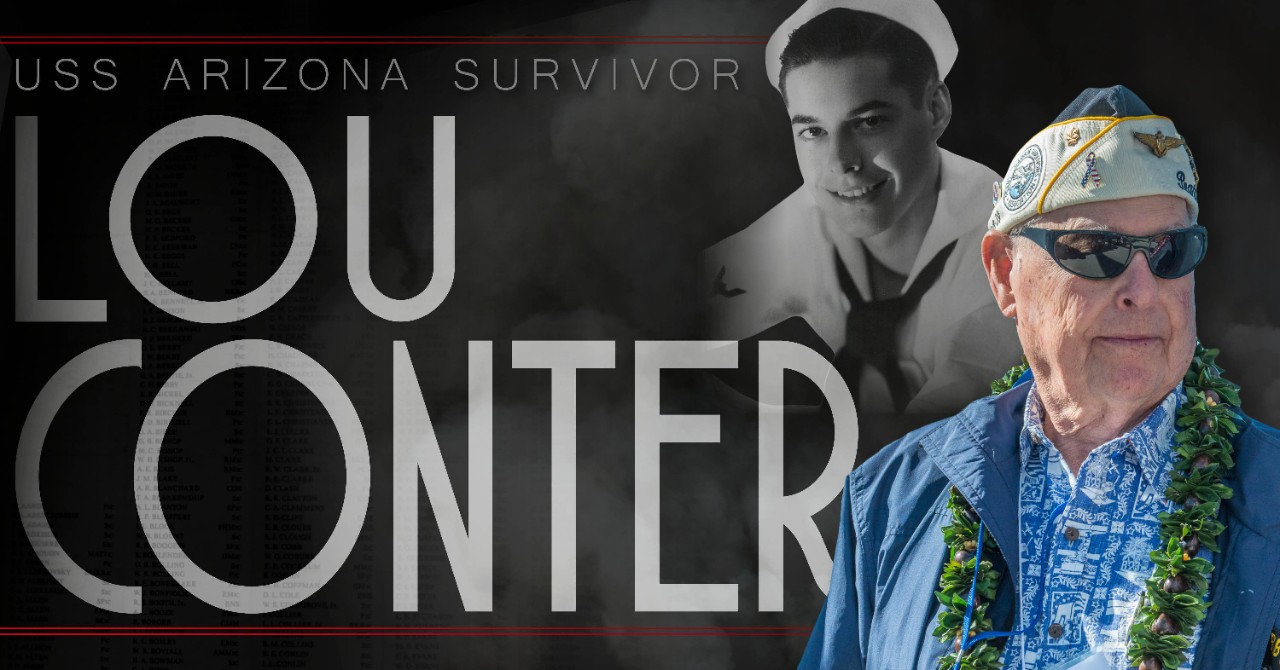

Last Survivor of Arizona Passes Away

On April 1, 2024, the last survivor from the crew of the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) during the Pearl Harbor attack has died. Lt. Cmdr. Louis A. “Lou” Conter passed away peacefully at his home in Grass Valley, California. He was 102. Born on Sept. 13, 1921, in Ojibwa, Wisconsin, to Nicholas and Lottie Conter, his family, to include two sisters, later moved to a farm outside Denver, Colorado. After he turned 18, Conter enlisted in the U.S. Navy in November 1939, where he was paid $17 a month. Following basic training at San Diego, he reported to his first ship, Arizona, at Long Beach, California, as an apprentice seaman. In March 1940, Arizona and the rest of the Battle Fleet were ordered to remain at Pearl Harbor following a major fleet exercise. On Nov. 1, 1941, Conter was selected for the enlisted pilot training program and received orders to return to the United States for training at Pensacola, Florida. Although he was scheduled to transit back aboard SS Lurline, his commander, Capt. Franklin Van Valkenburgh, directed him to remain onboard Arizona for a ride Stateside during a scheduled anti-aircraft weapons upgrade at Long Beach in December. Following a night-firing exercise, Arizona entered Pearl Harbor on Dec. 5 in company with battleships USS Nevada (BB-36) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37). The following day, Arizona took the repair ship USS Vestal (AR-1) on its port side.

On the morning of Dec. 7, Conter had just reported to the quarterdeck for duty as quartermaster of the watch when the first Japanese planes began to appear over the horizon. Japanese aircraft from six fleet carriers struck the Pacific Fleet as it lay in port, and in the ensuing two attack waves wreaked devastation on the battleship line and on air and military facilities defending Pearl Harbor. Onboard Arizona, the ship’s air raid alarm went off at about 7:55 a.m., and it went to general quarters soon thereafter. Conter was on his way to the bridge when a fourth bomb hit Arizona, which resulted in a catastrophic powder magazine explosion that killed or mortally wounded 1,177 of the 1,512 crew. During the attack, Conter rescued men from the flames, assisted in fighting fires, and helped evacuate the wounded. In all, Arizona alone suffered more than half the casualties of the Pearl Harbor attack. After the attack, Conter was assigned duty as a diver to go into the sunken ship to retrieve his fallen shipmates until it was deemed too dangerous to continue that work.

When the dust had settled at Pearl Harbor, Conter reported to Pensacola in January 1942 and completed flight school later that year. During World War II, he flew 2,000 flight hours during 200 combat missions as an enlisted pilot in PBY Catalina flying boats, mostly along the northern coast of New Guinea. He earned a Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in rescuing more than 200 Australian coastwatchers on New Guinea who had been trapped by a Japanese division’s surprise landing. During the war, Conter was shot down twice. In September 1943, his aircraft was hit by Japanese ground fire, forcing his burning plane to crash land into the ocean. Conter and the crew survived a day in the water, fighting off sharks, before reaching the shore and hiding in the jungle until they were rescued by an underwater demolition team. Two months later, Conter’s plane was shot down by friendly fire while attempting to rescue the crew of a U.S. Army Air Forces B-25 bomber. Although the nose gunner was killed, the rest of his crew survived and the B-25 crew was saved.

After the war, Conter was released from active duty, but he remained in the U.S. Naval Reserve. During periodic activations, he trained as an air intelligence officer. After North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, Conter was recalled to active duty and received training in the AD Skyraider single-engine attack bomber. In May 1951, he deployed in support of the Korean War as the air group intelligence officer onboard USS Bonhomme Richard (CV-31). During the deployment, Conter flew 29 missions in the Skyraider over North Korea and flew multiple coastal missions in support of guerilla insertion and intelligence collection.

After the Korean War, Conter was the first Navy officer to attend the Army’s Special Operations School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In 1955, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Navy’s first SERE (survival, evasion, resistance, and escape) courses at Brunswick, Maine, and North Island in San Diego. In 1958, in response to congressional complaints about the severity of SERE training, Cmdr. James Stockdale was ordered to go through the course incognito and report his assessment. After completing SERE training, Stockdale reported that it was the most demanding and challenging training he’d ever had, but also the best, and well worth it. After he was released from a North Vietnamese prison camp in 1973, Stockdale credited the SERE course for his survival. “Without that training, I would have never lived through my seven and a half years in a POW camp.”

Throughout the rest of his naval career, Conter conducted multiple sensitive clandestine intelligence collection and direct action missions. After establishing another SERE school in Hawaii, Conter retired from the U.S. Navy in December 1967 after 28 years of service. Following his service to the nation, he embarked on a successful career in real estate development.

In December 2019, Conter was the speaker at the interment of the ashes of Lauren Bruner, the last Arizona survivor to return to his shipmates aboard the battleship. He had attended the memorial service at Pearl Harbor almost every year since 1991. At the age of 99, he wrote an autobiography with authors Annette C. Hull and Warren R. Hull, The Lou Conter Story: From USS Arizona Survivor to Unsung American Hero. Conter is survived by his daughter Louann Daley, son’s James, Jeff, and Tony and stepson Ron Fudge. He also had numerous grandchildren, great grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. The family is scheduled to bury him on April 23 in Grass Valley, next to his late wife Valerie, who passed away in 2016. They were married for 45 years.

America Strikes Back

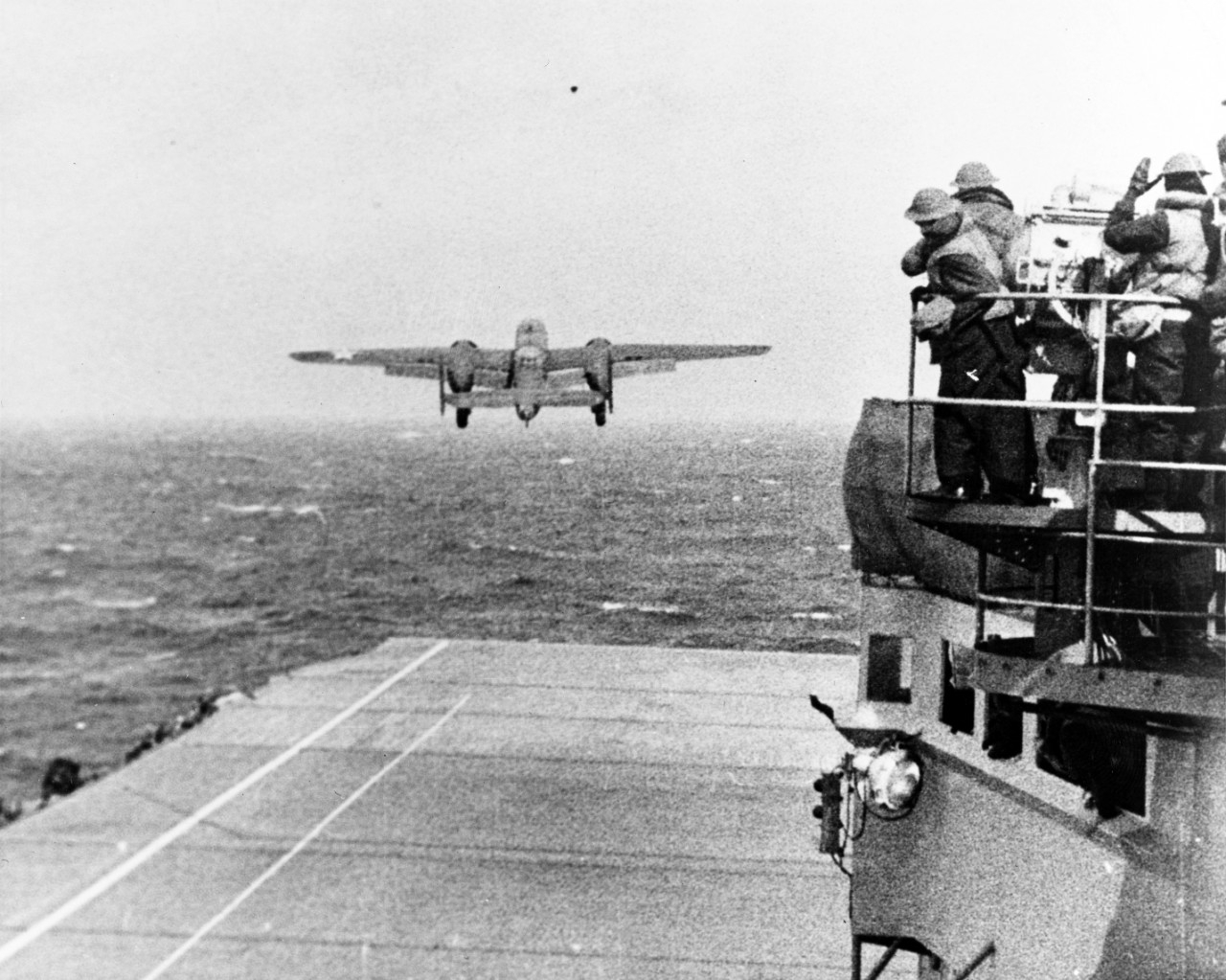

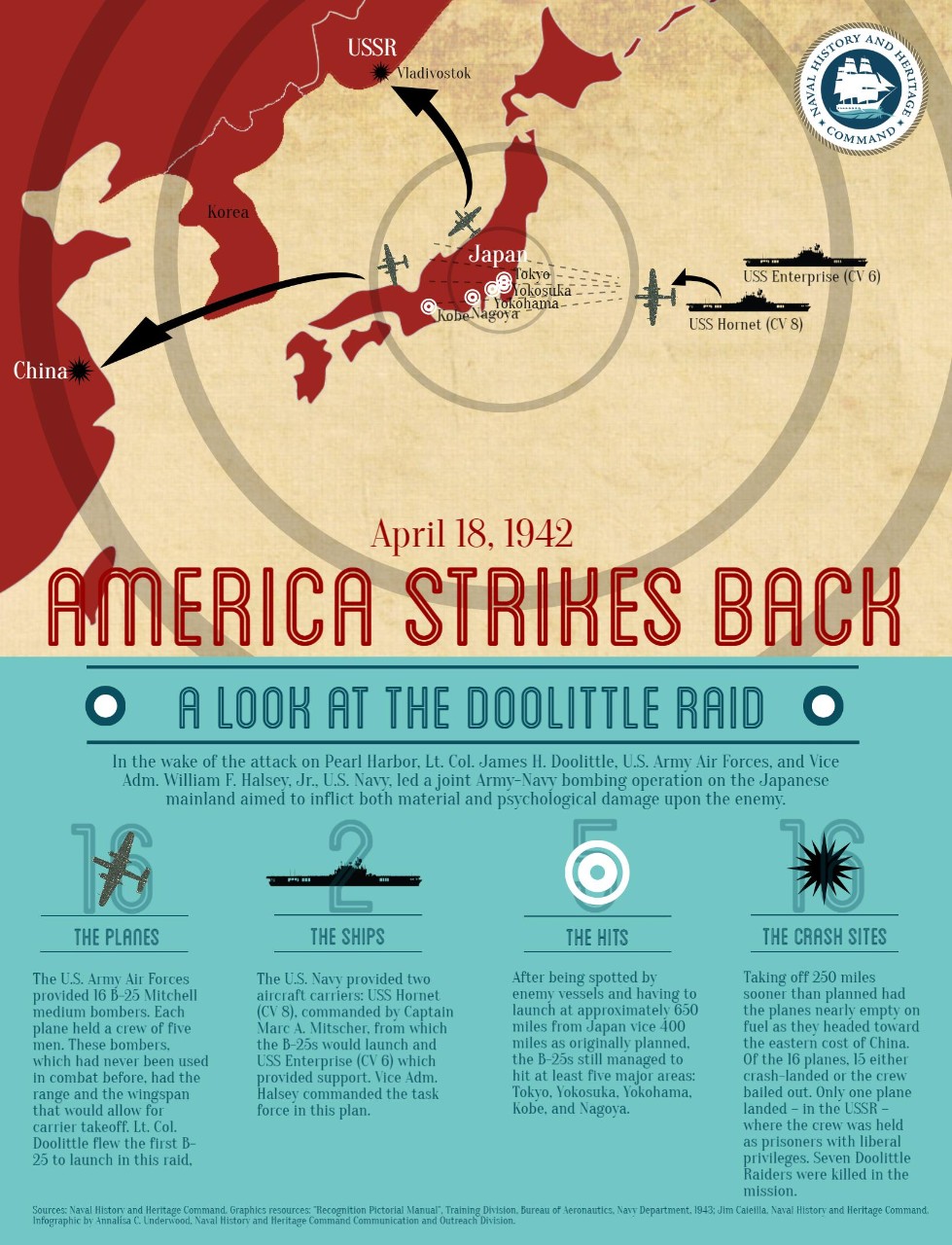

On April 18, 1942, 16 Army Air Forces B-25 bombers launched from the deck of aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) approximately 650 miles off Japan. The Doolittle Raid was conceived in the aftermath of the Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack, which marked the entry of the United States into World War II. The mission’s goal was to attack Japanese industrial centers in an effort to inflict both “material and psychological” damage on the enemy. Planners hoped the attack would provoke the enemy to recall forces elsewhere in the Pacific in order to defend its homeland. Originally, the plan called for bombers to be launched from, and recovered by, an aircraft carrier. Research disclosed that the North American B-25 Mitchell was the best-suited aircraft for the mission. Tests off Norfolk, Virginia, soon revealed that while a B-25 could take off with comparative ease, landing on a carrier was next to impossible.

Following this evaluation, planners decided to transport the aircraft to a point in the Pacific east of Tokyo. The first plane would drop incendiaries, the others would follow with high explosive bombs. The aircraft would then proceed to either the east coast of China or to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. However, Joseph Stalin’s unwillingness to provoke Japan compelled the selection of proposed landing sites to be in China. At a secret conference in San Francisco, Army Air Force Lt. Col. James Doolittle, who was designated to lead the attack, met with Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., who would command the task force that would take Doolittle’s aircraft within range of the Japanese Empire. They agreed the launch point would be somewhere within 600 miles due east from Tokyo, though, if discovered, Task Force 16 (TF-16) would launch the planes early.

In preparation for the mission, 24 planes were drawn from the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 17th Bombardment Group. The aircraft had additional fuel tanks installed, and all equipment deemed unnecessary was removed. In early 1942, intensive training began with the all-volunteer crews. The mission was considered extremely dangerous and would require a great amount of skill. Some even considered it a suicide mission. Crews practiced intensive cross-country flying, night flying, and navigation, as well as low-altitude approaches to targets, rapid bombing, and evasive action. Beginning on March 31, 16 B-25s were loaded onto Hornet at Alameda, California, and the ship steamed to rendezvous with aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) to form part of Halsey’s TF-16.

Monitoring U.S. Navy radio traffic, the Japanese deduced that a carrier-led attack on the home islands was a possibility after April 14. The Japanese were expecting the Americans to approach within 200 miles of Japan as they had done in early naval raids in the Marshalls and Gilberts, and at Wake and Marcus. In anticipation, the Japanese 26th Air Flotilla launched 29 medium bombers equipped with torpedoes, escorted by 24 carrier fighters equipped to find TF-16. On April 18, TF-16 was within 650 miles of Japan when one of the Japanese early-warning picket boats, which operated at intervals offshore, discovered the task force and radioed a sighting report. Although Halsey had agreed to take TF-16 closer to Japan, he recognized the potential for mission failure and ordered the 16 B-25s launched.

The deployment of long-range U.S. Army Air Force bombers took the Japanese by surprise. Taking a little over an hour to launch, the B-25s hit targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Kobe, and Nagoya, against little opposition. Bombs from the B-25s damaged aircraft carrier Ryuho at Yokosuka and thus delayed its completion. Of the 16 B-25s, 15 crashed in occupied China, where the Japanese inflicted brutal reprisals against the Chinese populace in the Chekiang province, who had aided the downed fliers. One B-25 landed intact at Vladivostok, where the Soviets interned it and its crew.

Although the material damage inflicted by Doolittle’s raiders proved minuscule, the psychological effect of the American air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous. Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed unlikely by the Japanese naval general staff, had occurred mostly unobstructed. The Doolittle Raid dissolved the residual doubts harbored within the naval general staff whether or not a thrust against the U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out the previously unengaged U.S. carriers, should be attempted. The Japanese army, previously reluctant about the operation, went along with the navy’s plan.

Maritime Mascots and Their Loyal Service

During World War II, June 26, 1945, was a tough day for U.S. Navy minesweepers. While operating at Balikpapan, Borneo, both YMS-39 and YMS-365 set off mines and sank. YMS-39 triggered a magnetic mine, partly disintegrated, capsized, and sank in less than one minute, losing four of its crew. YMS-365 triggered an influence mine and then hit a Japanese contact mine. Incredibly, no one was killed aboard YMS-365; however, 18 were wounded. While abandoning ship, some of the crew were initially trapped in the wreckage, including the commanding officer, which necessitated some heroic rescue efforts. Just as the ship broke in two, the last man was rescued. Well, almost the last. After the crew was safely on YMS-364, the mascot dog of YMS-365, “Doc,” was seen swimming out of the wreckage and perching himself on the capsized bow. After YMS-364 was ordered to sink YMS-365 with gunfire before it drifted to the Japanese-held shore, the survivors of YMS-365 implored the commanding officer to let them rescue the dog. After obtaining permission, YMS-364 backed within 25 feet of the floating hull, but attempts to get Doc to jump in the water and swim toward safety failed. So, Chief Motor Machinist’s Mate Edwin Johnson jumped into the water and swam toward the ship’s beloved mascot. Doc then jumped in the water and furiously “dog-paddled” to YMS-364, beating Johnson back to the ship. Doc, who had been aboard YMS-365 for more than two years, returned with the crew to California afterward, reportedly living happily ever after.

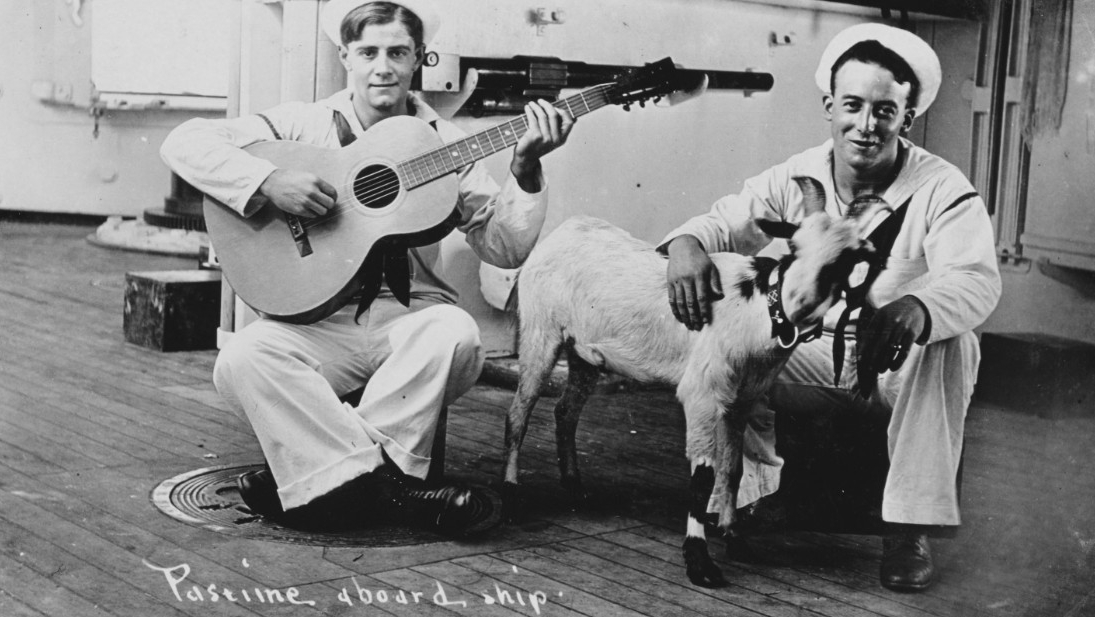

Mascots have a long history in the U.S. Navy. In the early days, larger ships kept livestock onboard as a source of fresh meat and milk. Exotic birds and monkeys were often part of the crew as well. Mascots usually served a meaningful purpose and provided companionship for Sailors on extended cruises. Cats were probably the most useful in terms of disease control. Dangerous to the crew, cats ate mice and rats that are often carriers of disease. In addition, rodents would often cause damage to ropes, woodwork, and electrical equipment as well as damage food supplies and cargos. Traditionally, Sailors have been known to be superstitious about cats and many considered them good luck. There have also been some obscure ship mascots. For example, auxiliary cruiser Buffalo hosted “Teddy,” an Alaskan bear cub, during the 1914 Alaskan Radio Expedition. From the late 1960s to early 1970s, a dwarf buffalo named Tamaraw joined the Navy from his native island of Mindoro in the Philippines. He even attained the rank of ensign and was issued “dog tags” and an identification card.

Probably the most recognizable mascots for the Navy that have stood the test of time are goats. In the early days, goats provided fresh milk, cheese, and butter and were the only livestock that was able to maintain “sea legs,” in any weather and under all conditions. Goats can eat anything as well. There was no need to store special feed as Sailors used goats as walking garbage disposals. In the early 20th century, goats began to serve a different purpose. The Navy’s first goat mascot, “El Cid,” was the pet aboard the armored cruiser New York. In 1893, crewmembers from the ship brought El Cid to Annapolis, Maryland, for the Army-Navy football game, which the Navy won 11–7. Midshipmen attributed the victory to the presence of the goat. From that point forward, the academy’s tradition of having a goat as a mascot was established. After the game, El Cid was renamed Bill. The name was borrowed from a pet goat kept by Cmdr. Colby M. Chester, commandant of the Naval Academy from 1891 to 1894. “Bill the Goat” is the official mascot of the U.S. Naval Academy to this day.

Some mascots have even become somewhat famous for their antics. Often featured in stateside newsreels and radio shows during World War II, Sinbad the four-legged Sailor was known to fancy boilermakers and draft beer in every watering hole from the New York docks to Boston’s Sculley Square. However, the biggest complaint about Sinbad was that he never paid for his drinks when ashore. Often known for his bad behavior and lack of discipline, he was court-martialed twice during his career—once for upsetting the locals by chasing sheep in Greenland and on another occasion for going AWOL in New York. Sinbad saw combat action (kind of) as well. On Feb. 22, 1943, USCGC Campbell (WPG-32) endured a 12-hour attack by six German submarines. During the engagement, Campbell rammed one of the submarines, nearly sinking it. Unfortunately, Sinbad snoozed through most of the attack. Regardless of his rowdy or sometimes lethargic behavior, Sinbad was so much a cherished part of the crew that when Samuel Eliot Morison had a coat of arms designed for Campbell, a drawing of Sinbad was placed on top. From loyal companions to working animals to famous friends, the loyal service of mascots has brought joy and comfort to those around them for centuries.

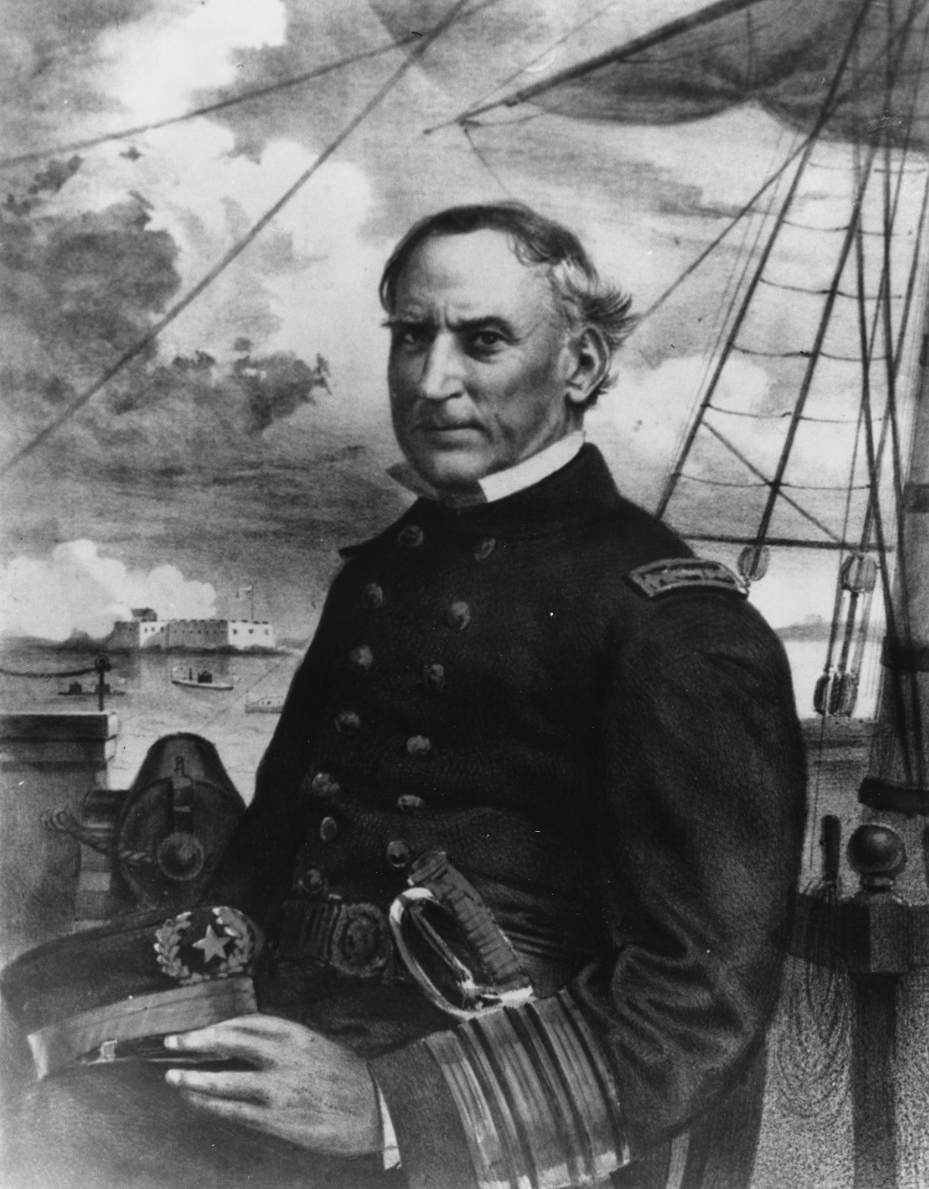

Today in Naval History—New Orleans Campaign

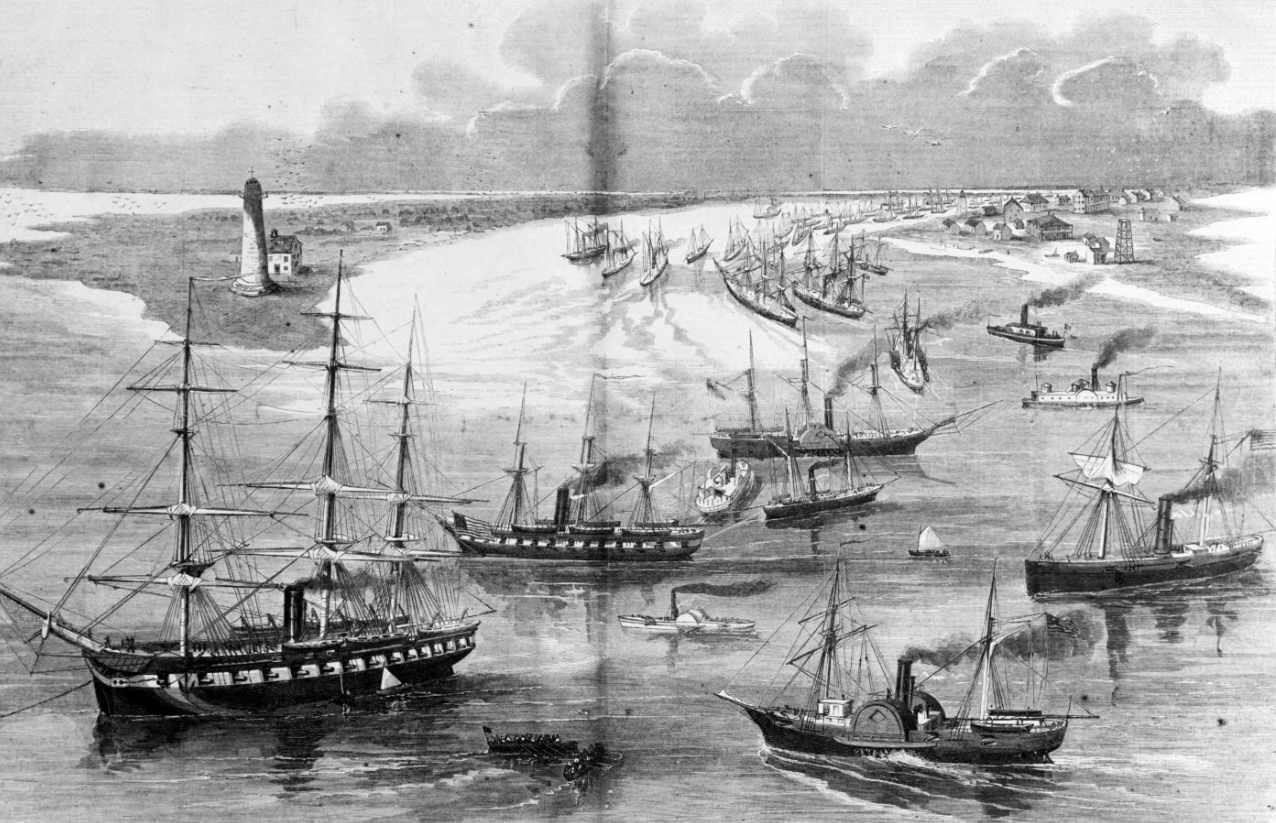

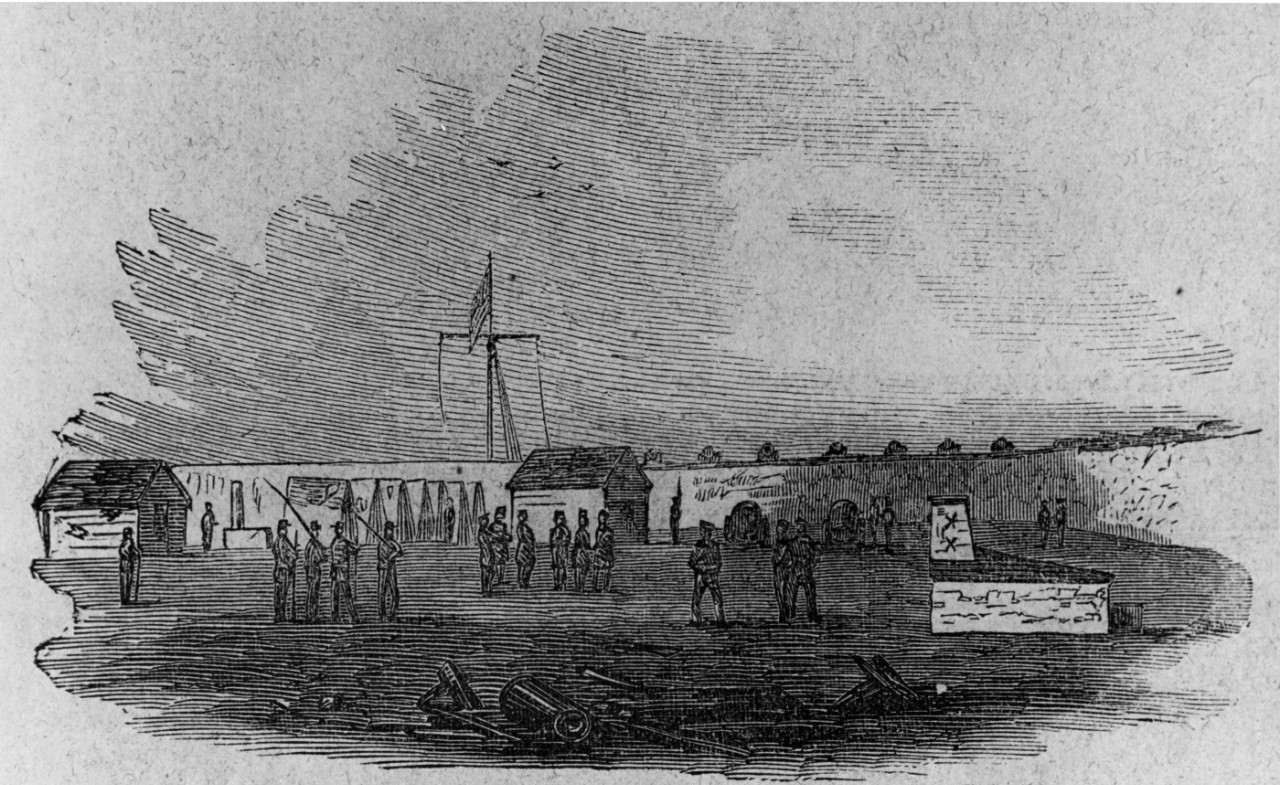

On April 16, 1862, during the Civil War, a U.S. Navy fleet under the command of Adm. David G. Farragut began its bombardment of Confederate fortifications at the mouth of the Mississippi River—Forts Jackson and St. Philip. During the first phase of the engagement, Lt. David D. Porter, who was charged with a semi-independent flotilla of mortar schooners to accompany Farragut’s force, fired long range into the forts. Most of the initial bombardment was focused on Fort Jackson due to its proximity and size. Porter believed that once Fort Jackson fell, St. Philip would follow shortly thereafter. Positioned behind a curve in the river and camouflaged by trees, it was difficult for the Confederate forts to return fire on Porter’s flotilla. After two days of attacks, Brig. Gen. Johnson K. Duncan, commander of both forts, sought additional help from the Confederate navy. Reluctantly, Capt. William Whittle designated the unfinished Louisiana as a floating battery to be placed above the forts in the river. Duncan requested the ironclad be positioned farther downstream, but Louisiana’s captain, Cmdr. Charles F. McIntosh, explained that the ship’s unfinished condition, especially its lack of steam power, did not allow the vessel to be placed directly under enemy fire. The ironclad was present only to help prevent the further intrusion of Farragut’s fleet.

Although return fire from the Confederate forts continued to fall short of the mortar fleet, the bombardment was not as successful as Farragut had hoped. He began to grow impatient and started preparing for the next phase of the attack. Reconnaissance of the forts and the approach to New Orleans revealed a defensive chain of hulks (sunken decommissioned ships) that stretched across the river just below the forts. Farragut ordered three Unadilla-class gunboats (Kineo, Itasca, and Pinola) to break the defensive chain. After three days, the crews of the gunboats managed to open a small gap in the barrier. Although not exactly what Farragut had in mind, the gap allowed his ships to pass in single file. At 2 a.m. on April 24, with his ships organized into three divisions, Farragut took advantage of the cover of darkness and ordered the attack. At 3:45 a.m., the forts began to fire on the first division under the command of Capt. Theodorus Bailey. Cayuga, Bailey’s flagship, was the first to pass the forts at around 4 a.m. and the first to engage the Confederate ships waiting above the forts. The first ships in Bailey’s division were able to engage much of the Confederate fleet before they were even able to get underway. As more ships from Bailey’s division passed the forts, it became a challenge distinguishing friend from foe, especially as the smoke from the exchange of fire began to fill the air. The last of the ships from Bailey’s first division mixed with Farragut’s heavy warships in the second division, but all remained afloat and continued forward through the gap. As they were forced to dodge burning rafts as they moved upriver, most of the Confederate defensive efforts seemed to be directed at the heaviest warships of Farragut’s division. The third and final division, under Capt. Henry Bell, was caught by heavy fire as daylight exposed their positions. Ultimately, 14 of the 17 Union ships made it past the forts. Confederate forces lost 12 ships, including ironclad ram Manassas.

After passing the forts, Farragut did not wait for the Army to continue the attack on the forts. Anchoring that night, his fleet was underway the following morning. After the batteries at Chalmette, Louisiana, were quickly silenced, Farragut anchored his ships off New Orleans on the afternoon of April 25, and Bailey was subsequently sent to demand the surrender of New Orleans. Confederate Maj. Gen. Mansfield Lovell had already evacuated his troops from the city, so it lacked any real military defense against the U.S. Navy’s guns. The mayor and the city council attempted to negotiate terms; however, after three days, Farragut grew tired of waiting for a surrender and sent a contingent ashore to run up the U.S. flag.

However, the battle for the forts was not over after Farragut’s ships passed up the river. Porter continued bombardment operations in preparation for a land assault by Army Gen. Benjamin Butler’s soldiers. After Farragut’s fleet had passed the forts, Butler assumed that Farragut’s fleet would wait for the Union Army before continuing to New Orleans. By the time Butler’s troops had landed on the Gulf-side crossing in the rear of Fort St. Philip, Farragut’s fleet was already in New Orleans and was unable to support an assault on the fort. Butler was disappointed with Farragut’s decision because he was unable to bring his troop transports to New Orleans until the forts had been reduced or had surrendered. Although he had brought scaling ladders to assault the rear of Fort St. Philip, he made no further attempt to do so. On the night of April 27–28, the garrison at Fort Jackson mutinied. Although this action did not directly affect Fort St. Philip, the incident and the interdependent nature of the two forts ultimately forced the surrender both of the forts to Porter.

On May 1, 1862, Butler and the Union Army took responsibility for the occupation of New Orleans. Farragut continued up the Mississippi River with his squadron to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He received the surrender of Baton Rouge and Natchez, Mississippi, before heading for Vicksburg, Mississippi, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. The Union victory at Memphis in June allowed the Western Gunboat Flotilla to descend to Vicksburg and rendezvous with Farragut in July 1862. A year later, the city of Vicksburg was under siege by combined U.S. forces under the command of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Porter. The Union occupation of New Orleans opened the way for a convergence on Vicksburg that wrestled control of the Mississippi River from the Confederacy.