Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Memphis

Tennessee

6 June 1862

Union Leadership:

Commander Charles H. Davis, U.S. Navy (USN)

Colonel Charles Ellet, Jr., U.S. Army (USA)

Confederate Leadership:

Captain Joseph E. Montgomery, River Defense Service

Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson, Missouri State Guard

BACKGROUND

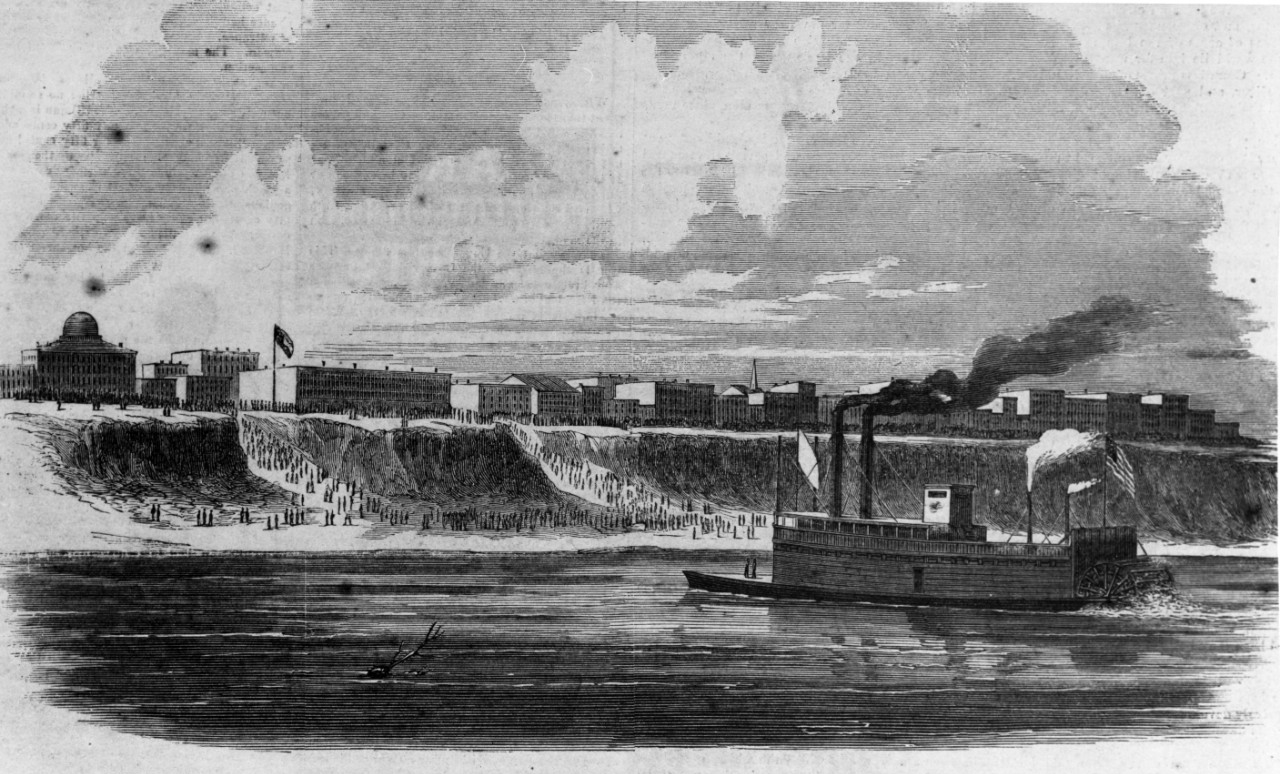

Map of the city of Memphis, Tennessee, including Fort Pickering and Hopefield, Arkansas, c. 1858 (Library of Congress [LC], 2012586237).

In 1860, cotton was the largest industry in the city of Memphis, Tennessee. [1] This inland port was shipping almost 400,000 bales of cotton in a year. The westward expansion of this labor-intensive industry gave rise to political tensions in 1861 that threatened to rip the state apart. In 1861, the debate over secession divided the electorate of Tennessee. Those in the mountainous eastern half of the state were inclined to remain in the Union. That does not mean that every citizen in west Tennessee was for secession. As this crisis intensified, as many as 5,000 citizens left Memphis for the North.[2] In June 1861, the state became the 11th and the last to secede despite contention within its borders. Among the demands upon joining the new confederacy, the state legislature called attention to the need to defend their western waters.[3] Rumors of Union shipbuilding upriver in Cairo, Illinois, sparked concerns, especially in the cities on the Mississippi River, which included Memphis.

In April 1861, the U.S. Navy had no presence on the Mississippi, but neither did the Confederacy. Both sides recognized the significance of controlling the Mississippi River. The U.S. Army cooperated with the Navy to establish a flotilla capable of descending from Cairo, with the goal of reclaiming control of the entire river navigation all the way to New Orleans. This joint venture quickly gained momentum until the Western Gunboat Flotilla had become a formidable opponent for the fledging Confederate Navy.

In March 1861, the new Confederate secretary of the navy, Stephen Mallory, received his first allocation of money. He immediately began acquiring vessels to convert into gunboats. However, Mallory knew that he would never be able to equal the number of vessels in the U.S. Navy. To combat this inequality, Mallory was determined to rely on technological innovation.[4] He wanted to do more than convert ships, he wanted to build ironclads. In August 1861, a Memphis riverboat operator, John T. Shirley, received a contract to build two ironclads. He started construction in October, but there were immediate delays due to lack of skilled labor and materials.[5]

While Shirley was struggling to build ironclads in Memphis, Commander John Rodgers, USN, handed over the first three converted gunboats of the U.S. Army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla—Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga—to Captain Andrew H. Foote. The first ironclads contracted by Rodgers were completed in January 1862. A few months later, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton authorized Colonel Charles Ellet, Jr., a civil engineer, to build a fleet of steam rams on the Mississippi River.[6] With the completion of Ellet’s rams, the U.S. Army now had two separate riverine commands operating on the Mississippi River in 1862.

The Confederate government, like their U.S. counterparts, divided responsibilities for defense on the Mississippi between their army and their navy. Captain George N. Hollins, Confederate States Navy (CSN), was in the command of the defenses afloat on the Mississippi River and off the coast of Louisiana.[7] Concern for the defense of New Orleans and the Mississippi River sparked a new initiative in January 1862. Joseph E. Montgomery and James H. Townsend, both former riverboat captains, received permission to establish a River Defense Fleet, independent of the Confederate Navy, based at New Orleans.[8] Montgomery became the commander of the small fleet.[9] Although acknowledged as a captain, he was not a commissioned officer in the Confederate Navy. In the spring of 1862, Montgomery and his fleet headed up the Mississippi River to support the Confederate Navy and to confront the U.S. Navy’s Western Gunboat Flotilla.

PRELUDE

After loss of Forts Henry and Donelson, Mallory ordered Hollins to take six gunboats to Memphis.[10] On 7 February, after hearing the news of Fort Henry’s fall, General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Confederate Army of the Mississippi, already seemed to know what came next. He wrote, “Island No. 10 and Fort Pillow will likewise be defended to the last extremity, aided also by Hollins’ gunboats, which will then retire to the vicinity of Memphis, where another bold stand will be made.”[11] Hollins’s small fleet lacked the numbers and the armament to challenge the Western Gunboat Flotilla. Hollins knew it, writing to Mallory, “I see nothing that I can do against them in fight.”[12] After the fall of New Madrid, Hollins transported the retreating Confederate soldiers across the Mississippi before retreating downriver.

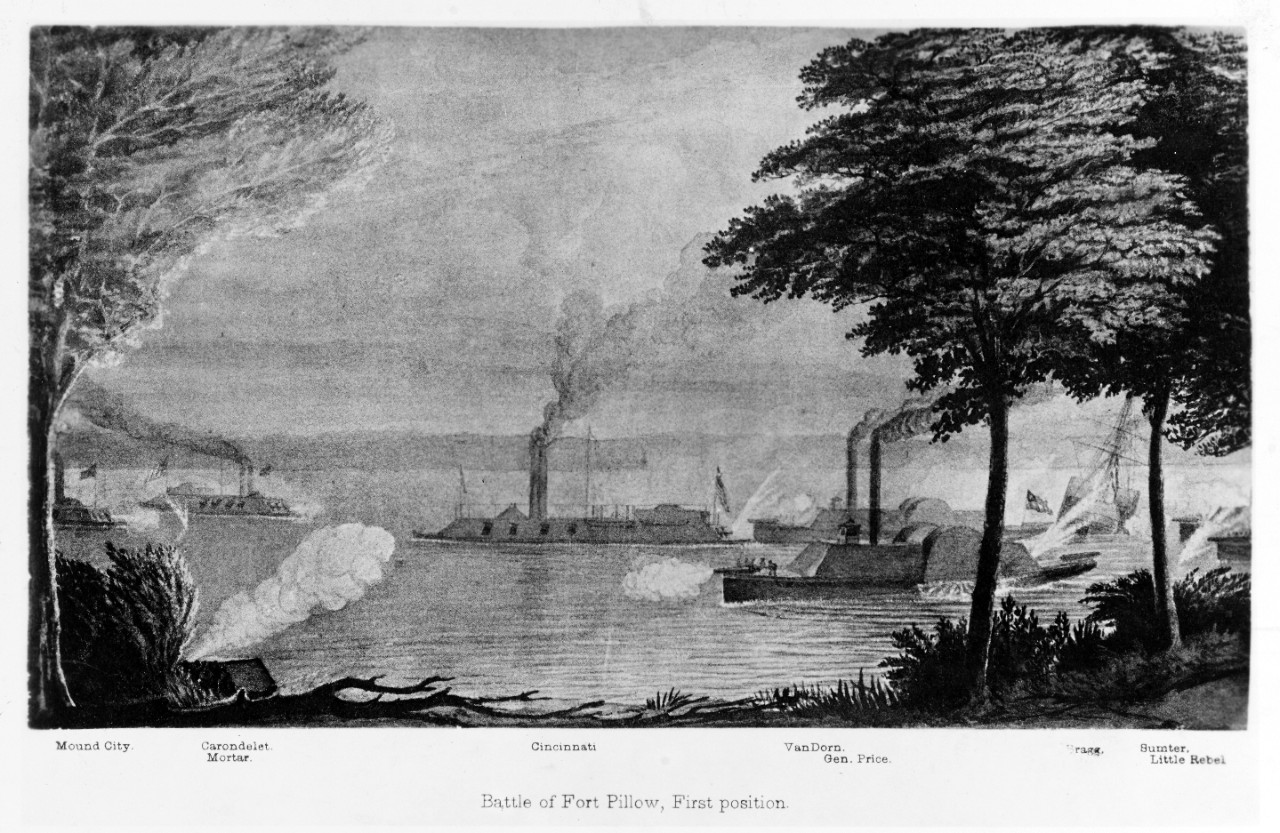

In March 1862, General Earl Van Dorn, General Bragg, and General Sterling Price, of Montgomery’s River Defense Fleet, were sent north to Memphis.[13] General Sumter and General Beauregard followed in April.[14] General M. Jeff Thompson and Little Rebel arrived on 11 April after completing their conversion to cotton-clad rams with “double pine bulkheads filled with compressed cotton bales.”[15] This ragtag fleet joined the Confederate flotilla at Fort Pillow following Hollins’s retreat from New Madrid.

On 10 April, Hollins wrote to Mallory that the enemy had passed Island No. 10. Mallory replied, “Do not let the enemy get the boats at Memphis.” The secretary of the navy also sent a telegram to Lieutenant Charles McBlair, CSN, based in Memphis. He advised him to hurry the completion of Arkansas.[16] The completion of the ironclad was essential to the Confederate Navy’s ability to preserve their control of the river’s navigation between Memphis and New Orleans.

Within a day of passing Island No. 10 with his flotilla, Foote advanced to Fort Pillow with seven gunboats: Benton, Cincinnati, Mound City, Cairo, St. Louis, Carondelet, and Pittsburg.[17] Pope and Foote planned for a joint attack on the fort. Before they could put their plan into action, Pope received new orders from his commanding officer. General Henry Halleck ordered Pope to lead his 21,000 soldiers to an advance on Corinth, which obligated Pope to abandon Foote and their plan to attack Fort Pillow. Pope left behind only two regiments, intended to land and occupy the fort only if the enemy abandoned it. After the departure of Pope’s army, Foote continued to use the mortar boats to harass the garrison of the fort, but he knew that the shrunken contingent left by Pope would not be able to hold the fort.[18] Foote put all his hopes for continuing his advance downriver on the fall of Corinth and the return of the Army of the Mississippi.[19]

While Foote felt that he could not advance without the army, his Confederate counterpart continued to retreat downstream. Hollins seemed to fear the enemy, refusing any direct confrontation. The support of his flotilla at the battle for New Madrid had slowed the Federal advance, but the Confederates could not stop it. After ferrying the retreating Confederate soldiers across the river to Tiptonville, Hollins had taken his gunboats further south to Fort Pillow to avoid any further confrontation with the enemy. At this point, Hollins received news from New Orleans that caused him to leave his post without waiting for a response from Mallory.[20] Command of the two remaining Confederate naval vessels near Fort Pillow—Livingston and General Polk֫—fell to his second in command.[21] Commander Robert Pinkney seemed to agree with Hollins that he could do little to stop the advance of the Federal flotilla. Due to his inaction, General Beauregard convinced Pinkney to remove his guns from his boats and mount them on shore at Randolph, five miles south of Fort Pillow.[22] General M. Jeff Thompson and his battalion, known as the “Swamp Rats,” joined the River Defense Fleet as sharpshooters and gunners aboard the vessels.[23] Montgomery arrived to command the vessels of the River Defense Fleet.[24] Neither Montgomery nor Thompson could convince Pinkney to attack the enemy.[25] Pinkney’s lack of initiative following the battle for Island No. 10 left the River Defense Fleet to act alone against Foote’s flotilla.

The stalemate at Fort Pillow allowed the work on the ironclads at Memphis to continue until 25 April. However, when news reached Lieutenant McBlair that the enemy had attacked New Orleans, he realized that he had run out of time. [26] He arranged to tow the newly commissioned Arkansas to Yazoo City north of Vicksburg on the Yazoo River. He ordered the unfinished Tennessee burned in the dry dock. With the fall of New Orleans, McBlair feared entrapment at Memphis between two advancing Federal flotillas. Running and hiding seemed to be the only option until he completed the construction of Arkansas.

Meanwhile, Foote waited for Pope’s return, but Halleck’s campaign against Corinth dragged on. Injured during the February attack on Fort Donelson, Foote suffered from a wound that refused to heal. On 9 May, Foote finally gave in to the pain and relinquished his command of the flotilla to Commander Charles H. Davis. Foote expected to return to the command of the flotilla,[27] but he never did. A day later, Montgomery finally sought to put an end to the siege of the fort.

Montgomery’s fleet at Fort Pillow consisted of eight vessels (with Colonel Lovell being the last to make the journey from New Orleans).[28] On the morning of 10 May, the Confederate rams left anchor and steamed toward the enemy. General Bragg and General Sumter headed straight for its target, the gunboat Cincinnati, which guarded the mortar boat firing on the fort.[29] Both of the Confederate rams struck Cincinnati. Both Cincinnati and Mound City fell out of the fight. The Federal flotilla managed to damage General Bragg, which drifted to safety. The battle was brief, barely one hour in length, but significant. It represented the first Confederate naval offensive on the Mississippi River. The Confederates claimed a victory in this last naval encounter before Memphis.

Ellet’s rams missed the encounter at the Plum Point Bend. Following his arrival on 25 May, Ellet immediately proposed a joint effort to run the batteries of Fort Pillow. Five days later, he was still waiting for a reply from Davis. When he did receive a reply, it was not the news that he wanted. Davis continued to decline to cooperate with Ellet. Davis did not seem to understand how Ellet fit in the command structure, even asking Ellet for clarification. Ellet explained that he was not under Davis’s authority and that he hoped to avoid another disaster as had recently occurred at Plum Point Bend.[30]

There would be no other opportunity for Ellet to prove himself at Fort Pillow. Following Beauregard’s withdrawal from Corinth, the garrison evacuated the fort on the night of 4–5 June. They also abandoned Randolph. Preparing to advance to Memphis, two Federal naval forces continued to operate separately despite their common purpose. Ellet had missed his chance to confront the enemy fleet below the fort. Davis made no mention of Ellet’s command during his preparations.[31] He remarked that if his fleet encountered the enemy before reaching Memphis that “they would detain us but a short time.”[32] Davis did not underestimate the enemy fleet, but he lacked Ellet’s impatience to confront it.

After leaving Fort Pillow, the River Defense Fleet fell back to Memphis to replenish their coal supplies.[33] Thompson requested the removal of his soldiers from the fleet. Thompson was not against cooperating with the fleet, but he could no longer tolerate his men serving aboard the vessels of the fleet.[34] The next day, he watched from the shoreline as the Federal fleet descended on the River Defense Fleet above Memphis. He was not the first to abandon Montgomery’s fleet to their fate. Pinkney retreated from Fort Randolph and kept going, running and hiding on the Yazoo River.[35] Only the remaining vessels of the River Defense Fleet waited to defend Memphis.

BATTLE

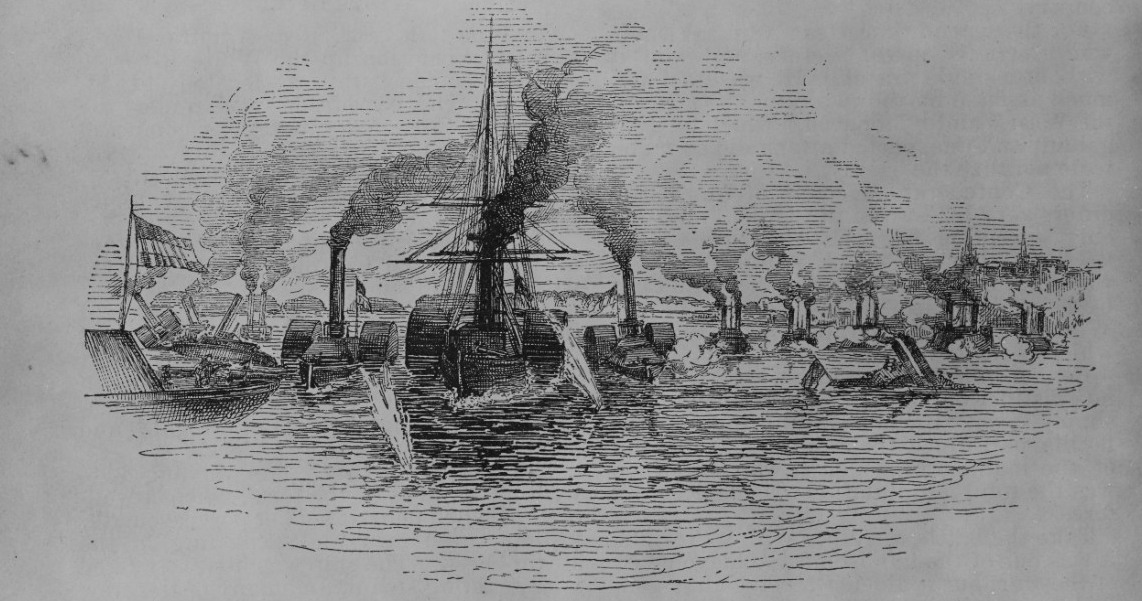

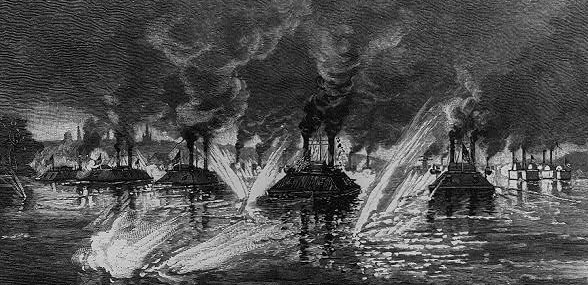

The Federal fleet advances south toward the Confederate fleet guarding the city of Memphis, 6 June 1862. (LC, 2004667779)

At 0400 on 6 June 1862, Carondelet, Benton, St. Louis, Cairo, and Louisville, under Davis’s command, approached Memphis. The gunboats were accompanied by four of Ellet’s rams—Queen of the West, Lancaster, Switzerland, and Monarch. As they approached, Monarch and Queen of the West led the way.

Watching the approach of the Federal gunboats, Thompson attempted to coordinate with Montgomery to provide reinforcements. Unfortunately, Thompson’s battalion was already at the railroad depot awaiting transport to Grenada. Montgomery asked Thompson to recall his men and await a tug at the landing at Fort Pickering, south of the city. [36] When Thompson arrived at the landing with his men, it was too late. All he could do was watch the confrontation unfold from the shoreline.

Montgomery did have enough coal to supply all of his vessels on a retreat to Vicksburg. Unwilling to destroy his fleet, Montgomery prepared to fight. Even without Thompson’s men acting sharpshooters and gunners, the rams were not helpless. Montgomery positioned General M. Jeff Thompson and Colonel Lovell above the city at the front of the action. What followed was confusion. Queen of the West immediately struck Colonel Lovell. Another blow from the Federal ram Monarch sunk the cotton-clad ram. CSS General Sumter retaliated, hitting and sinking Queen of the West. CSS General Price hit Lancaster (which remained afloat) before pursuing the ironclad Eastport, which quickly maneuvered out of harm’s way. General Beauregard and General Price collided with each other in the melee of battle. The burning General M. Jeff Thompson ran aground.[37] The crew abandoned the ship before its magazine blew up.[38]

A Federal ram, Monarch, struck the Confederate flagship, Little Rebel, and Montgomery was forced to abandon his ship.[39] His crew and he escaped ashore.[40] The U.S. Navy reported capturing 161 crewmembers in this battle,[41] but many more died in the water. Only General Van Dorn escaped destruction or capture, running and hiding up the Yazoo River. After helplessly watching the destruction of the fleet, Thompson and his cavalry left the city behind. With no army and no fleet, Thompson knew there was no hope of holding Memphis.[42] In one day, the U.S. Navy, working with Ellet’s rams, destroyed the River Defense Fleet, and the Confederacy lost Memphis.

AFTERMATH

The following day, the mayor surrendered the city of Memphis to Captain Davis. This victory solidified Federal control of western Tennessee and opened navigation of the Mississippi River all the way to Vicksburg. Occupied by the U.S. Army, the city became a base for future operations on the river.

In the aftermath of this surrender, the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, demanded inquiries into the reasoning for the retreat from Corinth and the failure to protect Memphis.[43] Davis seemed to understand that the loss of Memphis resulted from a series of events that started with the decision to abandon the Memphis and Charleston railroad. On the same day, Davis wrote to Brigadier General Martin L. Smith at Vicksburg, asking about the status of the ironclad Arkansas and the defenses at Vicksburg. He wrote that “Disasters above and below increase the value of your position.”[44] The enemy threatened Vicksburg from both sides now.

In Memphis, Davis and Ellet were busy raising the sunken enemy ships and arguing over which vessel was to be allocated to which flotilla, dividing the spoils of their victory. Utilizing the occupied navy yard, they repaired their vessels and prepared for the next action. Davis did not immediately proceed to Vicksburg out of caution. Before he found the courage move to Vicksburg, Halleck requested support from Davis for an army operation in northern Arkansas. Davis sent ships up the White River instead of down the Mississippi. This action delayed his move to Vicksburg for another two weeks. Finally, Farragut personally “invited” Davis to join him at Vicksburg.[45] Ellet’s rams were already there waiting with Farragut.

In the weeks after the battle, Charles Ellet suffered from a wound sustained during the action on 6 June. His brother, Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Ellet, assumed command of his fleet. Charles Ellet, Jr., died on 21 June while his brother was on his way to Vicksburg. Alfred made contact with Farragut after he arrived by sending soldiers across the peninsula to rendezvous with his fleet. Davis did not arrive until messages relayed by Ellet reached him. Davis finally left Memphis on the last day of June, leaving the city in the care of General Ulysses S. Grant, the district commander, who had recently established his headquarters there. The city remained under Federal control through the end of the war.

Vicksburg refused to surrender to Farragut in July 1862. The naval campaign to capture the city failed. Despite the cooperation of Davis, Ellet, and Farragut, this conquest demanded a joint operation and the U.S. Army remained engaged elsewhere in July 1862. The fall of Memphis cleared the way to Vicksburg, but Vicksburg was to hold out until July 1863.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

A Most Curious Battle: Memphis, June 6, 1862, Emerging Civil War.

The Battle of Memphis and Its Fallen Federal Leader, Emerging Civil War.

Battle of Memphis, Mariners’ Blog, the Mariners’ Museum and Park.

Memphis I, National Park Service.

FURTHER READING

Chatelain, Neil. Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2021.

Hearn, Chester G. Ellet's Brigade: The Strangest Outfit of All. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Joiner, Gary D. Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron. Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

Lewis, Gene D., Charles Ellet, Jr.: The Engineer and Individualist, 1810–1862. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1968.

McCaul, Edward B. To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Naval Campaign for Memphis. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2014.

Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. The Civil War on the Mississippi: Union Sailors, Gunboat Captains, and the Campaign to Control the River. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2016.

***

NOTES

[1] Wayne Dowdy, History of Cotton in Memphis, C-Span, 17 September 2018.

[2] Charles L. Lufkin, “The Northern Exodus from Memphis During the Secession Crisis,” West Tennessee Historical Society Papers 42 (1988): 6–29.

[3] J. Thomas Scharf, History of the Confederate States Navy (New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1887), 303.

[4] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereafter ORN), 30 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1894–1922), Series 2, Vol. 2 (1921) 69.

[5] ORN, 2, 1 (1921), 782–83.

[6] ORN, 1, 23 (1910), 106.

[7] U.S. Navy Department, Office of Naval Records and Library, Register of Officers of the Confederate States Navy, 1861-1865 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1931), 91; read more about George N. Hollins on the blog Emerging Civil War.

[8] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter ORA), 128 vols. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 52, Pt. 1 (1898), 37; Edward B. McCaul, Jr., To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Naval Campaign for Memphis (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2014), 13.

[9] McCaul, 14.

[10] ORN, 1, 22 (1908), 824.

[11] ORA, 1, 7 (1882), 862.

[12] ORN, 2, 1, 519.

[13] James L. Mooney, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy,, 1963), 522—23.

[14] Mooney, 522, 525.

[15] Mooney, 524–5.

[16] ORN, 2, 1, 798.

[17] ORN, 1, 23, 3.

[18] ORN, 1, 23, 71.

[19] ORN, 1, 23, 9.

[20] ORN, 1, 22, 842.

[21] ORN, 2, 1, 520.

[22] ORN, 1, 23, 697–98; ORN, 1, 23, 54.

[23] ORN, 1, 23, 26, 57.

[24] ORA, 1, 52, pt. 1, 38.

[25] McCaul, 89.

[26] ORN, 2, 1, 798.

[27] ORN, 1, 23, 22.

[28] Mooney, 510.

[29] ORN, 1, 23, 54.

[30] ORN, 1, 23, 36–39.

[31] ORN, 1, 23, 47–48.

[32] ORN, 1, 23, 54.

[33] ORA, 1, 52, pt. 1, 39.

[34] ORN, 1, 23, 699–700.

[35] Scharf, 338.

[36] ORA, 1, 10, pt. 1, 913.

[37] ORA, 1, 52, pt. 1, 39–40.

[38] “General M. Jeff Thompson,” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), last accessed 13 June 2022.

[39] “Little Rebel,” NHHC, last accessed 13 June 2022.

[40] ORA, 1, 52, pt. 1, 39.

[41] ORA, 1, 52, pt. 40

[42] ORA, 1, 10, pt. 1, 913.

[43] ORA, 10, pt. 1, 786.

[44] ORA, 15, 754.

[45] ORN, 1, 23, 231.