Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Forts Henry and Donelson

Tennessee

6–16 February 1862

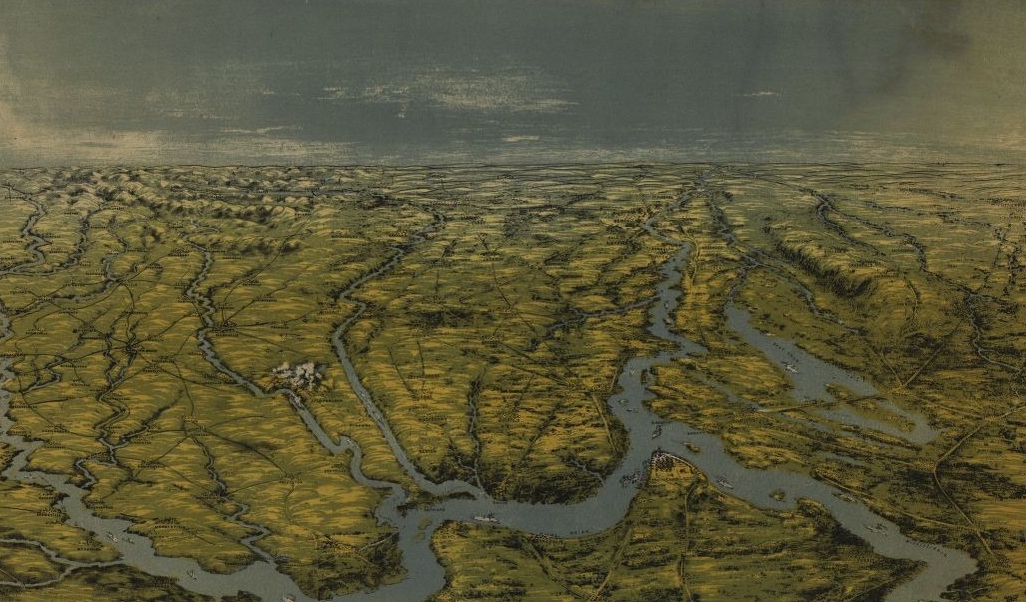

Panoramic view looking south from Cairo, Illinois, showing parts of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas. (Library of Congress [LC], 99447069)

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, United States Navy (USN)

Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, U.S Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Fort Henry

Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, Confederate States Army (CSA)

Fort Donelson

Brigadier General John Floyd, CSA

Brigadier General Gideon Pillow, CSA

Brigadier General Simon Buckner, CSA

BACKGROUND

The electorate of Tennessee initially voted against secession in February 1861. After the call to arms in April, the governor of Tennessee, Isham Harris, refused to send troops to support the federal government.[1] Harris did not wait for the state legislature to make a final decision on secession and appointed Gideon Pillow in charge of the organization of a provisional army for the defense of Tennessee. Confederate Secretary of War Leroy P. Walker wrote to Harris with the confidence that Tennessee would soon join the Confederacy.[2] Without a navy, fortifications built on the banks of the western rivers were the South’s best option for defending its inland waterways. Walker requested permission from the governor to build a defensive fortification on the banks of the Mississippi River at Memphis. Harris assured Walker of his loyalty to the Confederate cause and promised the fulfillment of Walker’s request. In April 1861, Harris began planning for the defense of his state as if the state legislature had already voted in favor of secession.

Harris’ ambition to protect the largest artery for commerce and communication in his dominion left him blind to the holes in his planning. The defenses along the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers were neglected compared to those on the Mississippi river. Harris may have been overconfident in the continued neutrality of Kentucky in this conflict, but he did his due diligence in the defense of his state. In May 1861, Brigadier General Daniel S. Donelson led a surveying team along the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers. The engineers assigned to the team, Adna Anderson and William F. Foster, selected sites for two forts between the two rivers. The first site that they selected was located on the western bank of the Cumberland, and a second site was on the eastern bank of the Tennessee. The site on the Cumberland River was never challenged by the team leadership, but the site on the Tennessee river was moved twice. The final position on the Tennessee River was not the one that the engineers had selected.

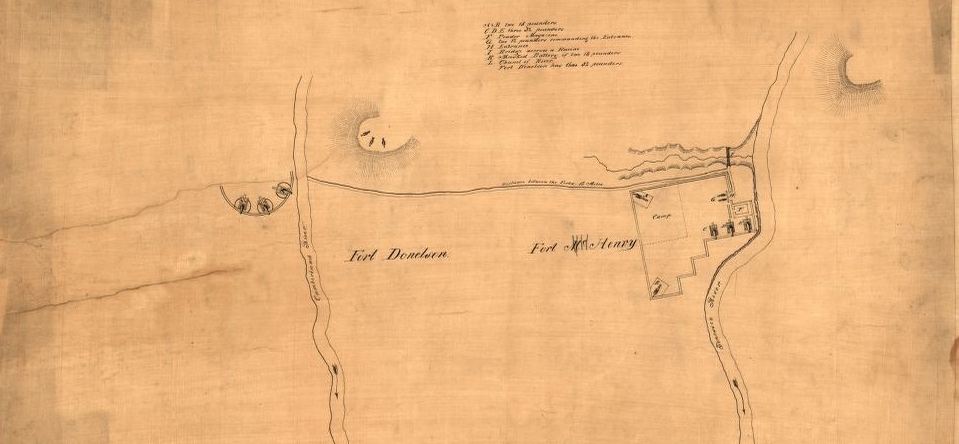

Original map depicting Forts Henry and Donelson, 1862. This map is not drawn to scale. (LC, 80691156)

Whether it was Harris’s influence or the will of the people, Tennessee became the last state to dissolve its connection with the federal government in June 1861. On June 29, the provisional army of Tennessee formally transferred into service of the Confederacy. The state-appointed leader of the provisional army, Gideon Pillow, did not receive the commission to major general that he had expected. Instead, he was granted a commission as a brigadier general assigned to Major General Leonidas Polk.[3] Polk hurried to fortify his positions along the Mississippi river. The defense of the Mississippi River was the top priority to the Confederate high command, but not high enough. In December 1861, Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory did begin planning for the construction and conversion of vessels to establish a fleet on the Mississippi River.[4] However, the facilities, manpower, and funding for shipbuilding along the Mississippi were limited. The Confederate navy was still almost non-existent on the river in the spring of 1862.

To the north, Governor Richard Yates mobilized his state of Illinois to oppose this rebellion within three days of the surrender of Fort Sumter. He swiftly safeguarded the state’s southernmost town of Cairo at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.[5] He believed this position was vital to the movement of U.S. forces on the western rivers, and he was correct. The U.S. Army soon established a base of operations at Cairo and began stopping river traffic headed south.

In April 1861, Winfield Scott, commander in chief of the U.S. Army, presented the “Anaconda” plan, which included a general blockade of the coast and a joint movement down the Mississippi River. The problem was that there was no Navy presence on inland waterways in April 1861. All inland waterways were under the jurisdiction of the War Department. Secretary of Navy Gideon Welles did not wish to assume more responsibilities, but he did send Commander John Rodgers to serve as an advisor. In this new role, Rodgers served under the supervision and bankroll of the War Department.[6] Within three months of his arrival in Cairo, Rodgers established a small flotilla of converted riverboats on the Mississippi.

At the end of August, the fleet consisted of three timberclads and nine ironclads with a contract for 38 mortar boats. Despite this accomplishment, Rodgers had often overstepped his purview. Welles bowed to pressure from Major General John C. Fremont and replaced Rodgers with a more senior officer. In September, Captain Andrew H. Foote arrived to take command of the new Western Flotilla.[7] Despite frustration with his orphaned command, Foote did his best with limited resources and frequent, carefully worded letters to his superiors.[8] Foote understood his obligation to cooperate fully with the Army in the campaign for control of the Mississippi River.

In the same month as Captain Foote’s arrival in Cairo, the new Army commander of the District of Southeast Missouri arrived there: Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant. The two officers had a bit of a rocky start with arguments centered around the sharing of resources, but they at least agreed on the need for coordinated movements against the enemy. Within a week of their introduction, Grant and Foote engaged in their first joint operation: the seizure of Paducah in the neutral state of Kentucky. The capture of Paducah solidified a line of advance down the Cumberland River and provided an excellent vantage point for the Western Flotilla to observe the enemy fortifications and prepare to break through their line of defense at its center.

PRELUDE

In September 1861, Major General Albert Sidney Johnston took over the command of Department No. 2 in the western theater, with Polk acting as his subordinate. The size of this department had grown since June. Johnston controlled an area that amounted to two thirds of the new Confederacy. Johnston sent Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman to take command of both Fort Henry and Donelson. As an engineer, Tilghman immediately understood the vulnerability of Fort Henry. He assigned a contingent to build a new fort on the high bluffs of the opposite bank, which had previously been unacceptable because of the neutrality of Kentucky. Construction began in December, but it was not yet equipped in February 1862 when the U.S. forces mobilized for movement down the Tennessee River. Johnston and Tilghman knew their weak point, but they had no time to correct the mistake before the spring floods brought the U.S. forces up the river from Paducah.

Brigadier General Charles F. Smith began gathering intelligence as soon as he received command at Paducah in September. He accompanied river patrols upstream to determine the strength of the forts on the two rivers.[9] On 22 January, Lexington came into range of the guns at Fort Henry for a brief and uneventful exchange of fire during a final reconnaissance mission.[10] The high water of the spring months was ideal for this campaign as the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers could only be navigated by small steamers throughout most of the year. When General Frémont was replaced, Grant sought approval of the new commander, General Henry Halleck, to attack Fort Henry. Both Foote and Grant wrote to Halleck for permission to move against Fort Henry with their combined forces.[11] On 27 January, Lincoln impatiently issued General War Order No. 1, which required a combined Union advance within a month. On 30 January, Halleck finally gave permission for an assault on Fort Henry. The combined influence of Lincoln, Grant, and Foote ultimately had the desired effect of moving Halleck to acquiesce to Grant’s plan of attack.

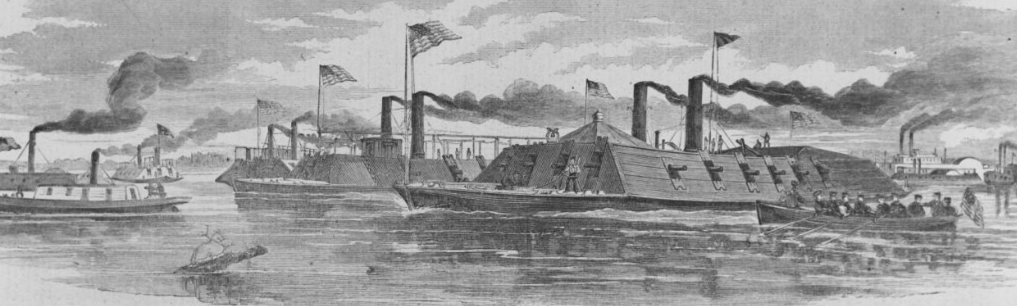

Western Gunboat Flotilla afloat on the Mississippi River, including (left to right) Mound City, Essex, Cairo, Saint Louis, Louisville, Benton, Pittsburg, and Lexington. This is a line engraving based on a sketch by Alexander Simplot. published in Harper's Weekly, 1862. (Naval History and Heritage Command [NHHC], NH 59002)

THE BATTLE

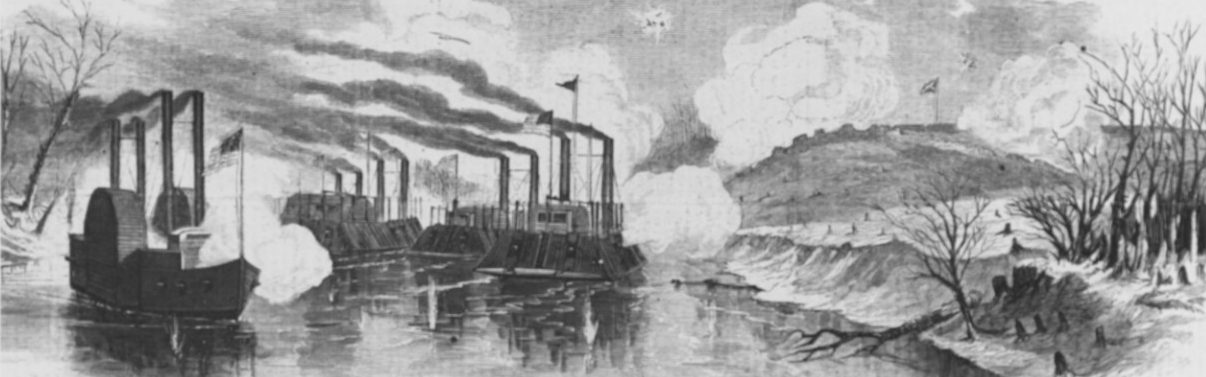

On 2 February, Foote’s expedition departed from Cairo. The Union fleet numbered seven gunboats, including four ironclads—Cincinnati, Essex, Carondelet, and St. Louis— and three timberclads—Conestoga, Tyler, and Lexington. The army transports followed, carrying most of the 15,000 soldiers. One company was assigned to the gunboats as sharpshooters.[12] Grant and his forces planned to move overland from their encampment five miles north to Fort Henry. Heavy rains delayed this march, and the same rain that bogged down the land forces aided the gunboats in arriving at their destination ahead of their land complement. The mines anchored by the Confederates on the river bottom in the approaches to the fort were also rendered useless by the high water levels. At noon on 6 February, Foote commenced his attack on the fort without Grant.

With the ironclads in the front, the fleet approached Fort Henry. The firing began at 1,700 yards and continued unabated until the vessels were within reach of the fort’s guns. The U.S. Navy gunboats outgunned the fort and Tilgman knew that he would not be able to hold it. He began sending his troops overland to Fort Donelson. He stayed with his artillerymen to distract the gunboats as a trail of retreating soldiers exited the rear of the fort. The Confederate artillery fired until seven of their 11 guns were rendered useless. Tilghman surrendered his nearly empty fort to Foote before Grant’s troops arrived on foot. The small contingent of gunboats completed their work almost unscathed—only Essex was damaged by the return fire from the fort. Twenty-nine of her crew, including her commander, Captain David Dixon Porter, were among those injured in the brief exchange. Grant reported his victory to Halleck, declaring that “Fort Henry is ours. The gunboats silenced the batteries before the investment was completed.”[13] After the surrender of the fort, Foote secured the prisoners and moved forward with plans to destroy the railroad bridge farther south over the Tennessee River, which connected Bowling Green to Columbus. It seemed like earthen fortifications were no match for the ironclad gunboats.

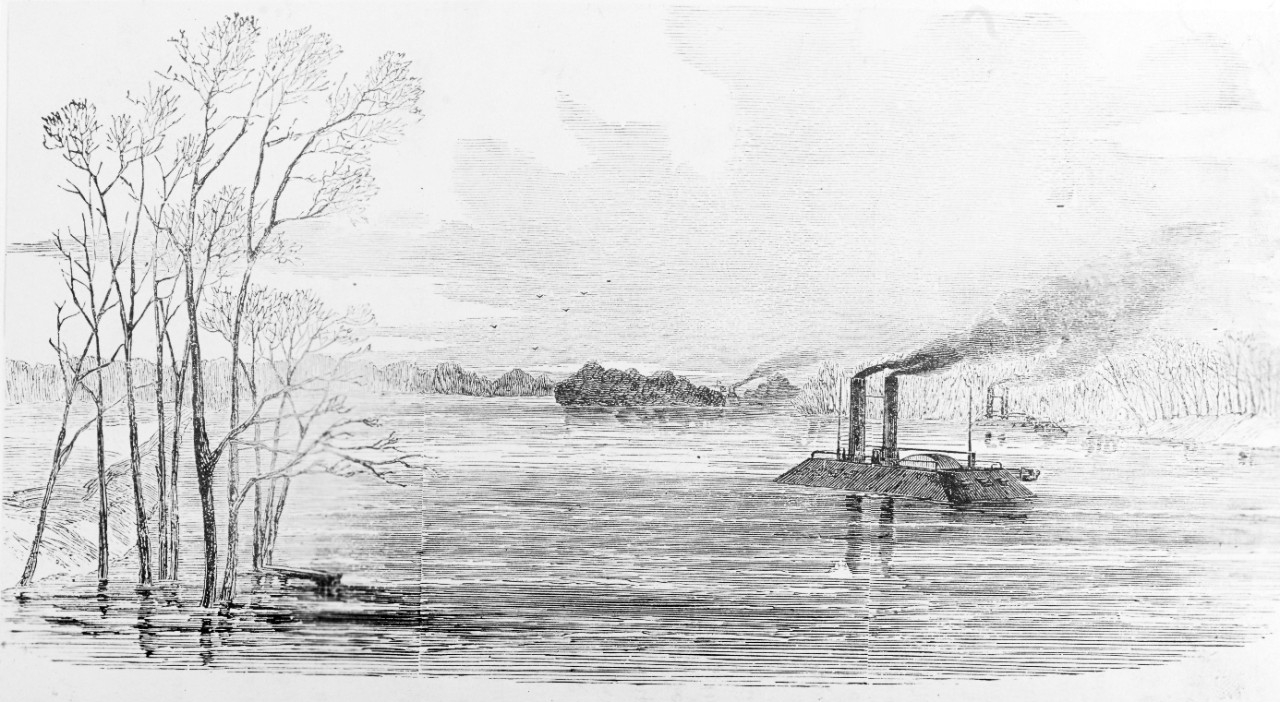

With no other obstacles in his way, Lieutenant Seth Phelps followed Foote’s plan to destroy the railroad bridge to the south. Reaching the bridge, Phelps spotted a group of Confederate steamers in retreat. He left the crew of Tyler to see to the bridge while he pursued the enemy. Five hours later, all three Confederate steamers—Samuel Orr, Appleton Belle, and Lynn Boyd—were destroyed by their own sailors.[14] Further ascending the river, Phelps captured a half-finished Confederate vessel, Eastport.[15] The flotilla reached the state line with Alabama, three hundred miles from the mouth of the Tennessee River. As they approached Florence, Confederates torched three more steamboats—Sam Kirkman, Julius Smith, and Dunbar—to prevent their capture.[16] Despite these efforts, the timberclad contingent successfully captured three steamers—Sallie Wood, Muscle, and Eastport. Eastport was quite a prize as she was already being prepared for conversion to an ironclad. After reaching Florence, the timberclads were recalled north to support the attack on Fort Donelson.

After the fall of Fort Henry, Foote had returned with his damaged vessels to Cairo for repairs. Nevertheless, Grant was determined to move on to Fort Donelson.[17] He performed his reconnaissance and awaited the cooperation of Foote and his gunboats. On the morning of the 12th, Grant decided to put his 15,000 soldiers in motion. Over the next two days, Grant’s forces surrounded the fort. In response to Grant’s movement, Johnston sent reinforcements under Brigadier General John B. Floyd to Fort Donelson. These reinforcements arrived before Grant had encircled the fort and before Foote’s gunboats.

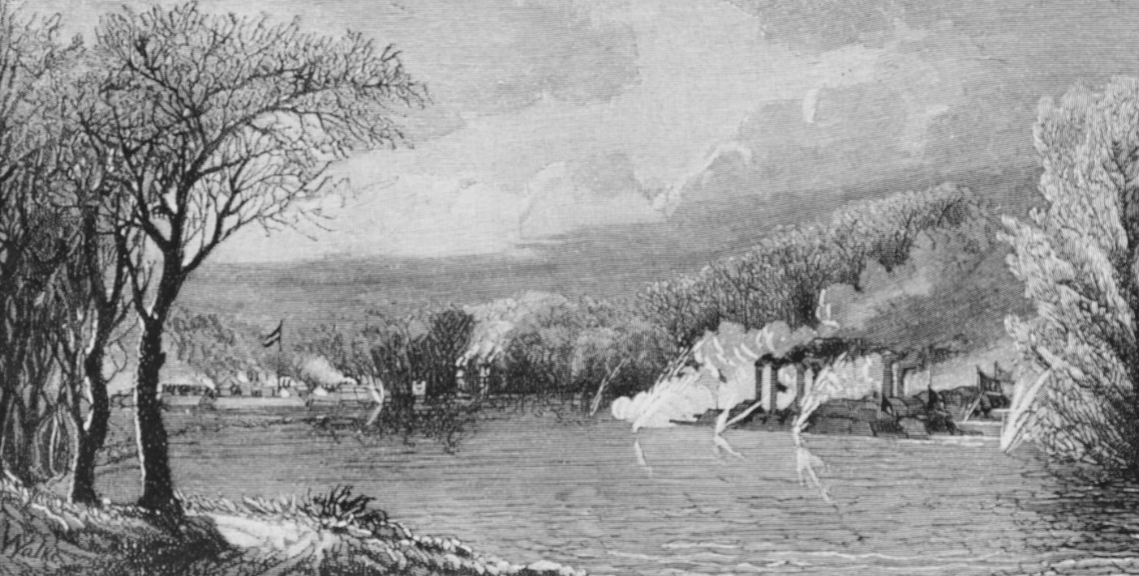

Although Foote felt that this movement to Fort Donelson was unnecessarily urgent, he conceded to the urging from both Grant and Halleck.[18] He quickly transferred men from the disabled boats and prepared to leave Cairo again. After he recalled the timberclads from their mission on the Tennessee river, Foote left Cairo with four of his ironclad steamers—Carondelet, Louisville, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.[19] Carondelet was the first of the gunboats to arrive on scene at Fort Donelson on the evening of 13 February. The next morning at 0900, Foote and Grant were in consultation. Foote wanted to wait for the mortar boats, but Grant wanted him to attempt to recreate his success at Fort Henry. Unfortunately for Foote, the batteries at Fort Donelson were better emplaced, and therefore had a more effective field of fire. At point-blank range, the fire from the fort disabled three of the four ironclads within a few hours.[20] Foote himself was injured during the bombardment while aboard St. Louis. The gunboats were forced to fall back. Grant began preparing for a siege, and the three Confederate brigadier generals inside the fort planned their next move.

Before the naval bombardment, the Confederate command at the fort had intended to attack the land forces that were quickly surrounding them. Following the capture of Fort Henry, General Johnston knew the risk to the stability of the center of his defensive line. He wrote, “The capture of that fort by the enemy gives them the control of the navigation of the Tennessee River, and their gunboats are now ascending the river to Florence.... Should Fort Donelson be taken it will open the route to the enemy to Nashville.”[21] Planning for every contingency, he saw the threat posed by the Union gunboats and he prepared his forces in the area to fall back to Nashville if Fort Donelson fell.

U.S. Navy detachment from Western Gunboat Flotilla bombards the water batteries at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, 14 February 1862. Left to right: Tyler, Conestoga, Carondelet, Pittsburg, Louisville, and St. Louis. This line engraving is based on a sketch by Alexander Simplot later published in Harper's Weekly in 1862. (NHHC, NH 58898)

Arriving with the reinforcements arrived, Brigadier General John B. Floyd had assumed command of Fort Donelson. He was undeniably caught off guard by the entire battle. The advice of his subordinates, Gideon Pillow and Simon Buckner, did not improve upon his indecisiveness. In a final effort to break out of the fort, Buckner and Pillow attacked the entrenched enemy with Pillow advancing on the right. Fire from Louisville and St. Louis lent support to Grant’s divisions as they drove back the Confederates.[22] This attempt by the besieged forces fell short of success as Pillow prematurely ended his sally and retreated back to the fort. After a series of changes in command for personal reasons, Floyd and Pillow left with their aides in the night. For their abandonment of their post, both of them were later relieved of command. Disgusted by his superiors, Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest received permission from Buckner to fight his way out with his Confederate cavalry before the surrender. Brigadier General Simon B. Buckner was left to request terms for surrender for approximately 15,000 soldiers under his command.[23] Grant responded that only an unconditional and immediate surrender would be accepted. Soon after, Buckner acceded to these terms, surrendering Fort Donelson and its garrison.

AFTERMATH

The success of the U.S. forces on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers forced a general retreat of the Confederate forces in the western theater. Polk prepared to abandon Columbus, and those forces on the left flank fell back to Nashville. Tennessee was now vulnerable. Following this defeat, Governor Harris offered all possible resources to Johnston in exchange for the protection of the state of Tennessee. He was informed that Johnston intended to offer no further defense of Nashville.[24] General Johnston instructed Polk to begin withdrawing his forces south to New Madrid.

In celebration of the successful capture of Fort Henry, General Halleck wrote to Washington: “The flag of the Union is re-established on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed.”[25] After the surrender of Fort Donelson, Foote returned to Cairo to carry out repairs and to prepare for what he expected to be a continuation of the campaign on the Cumberland river. A few days later, he left Cairo, aboard Conestoga, for an armed reconnaissance along the Cumberland. Halleck had given orders to Grant that the gunboats should not go beyond Clarksville. Foote later claimed he never received any relay of these orders from Grant, but he went only as a far as Clarksville.[26] He arrived to find the town deserted. The way was clear, but the Army command delayed any further advance beyond Clarksville.

Although both Grant and Foote agreed that the best way to make good on their success was an advance toward Nashville, Grant’s superiors disagreed. General McClellan gave orders to ready gunboats for a demonstration at Columbus on the Mississippi River.[27] After two days of back-and-forth telegrams, Foote finally conceded to an armed reconnaissance toward Columbus.[28] Foote was frustrated with this distraction from the movement toward Nashville. He wrote to his wife that “It was jealousy on the part of McClellan and Halleck.”[29] He was determined to be independent from now on and only to follow the orders of the Secretary of the Navy or the President himself.[30] Although the cooperation between Grant and Foote successfully won Forts Henry and Donelson, the infighting within the Army command triggered a breakdown in Foote’s willingness to serve at the discretion of the Army.[31]

The high waters in the spring of 1862 continued to allow the flotilla to ascend the rivers to Nashville, but there was no further advance in February.[32] Foote continued to operate reconnaissance missions along the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers while he waited for a plan from the army.[33] He resented the delay, which he blamed on Halleck. [34] In the last week of February, Nashville was abandoned by the enemy before Foote was granted orders to attack. The gunboats finally reached the empty city in March.

Foote continued to command the Western Flotilla until May 1862 despite the injury to his foot received during the bombardment of Fort Donelson. As the focus shifted back to the Mississippi River after the fall of Nashville, Foote had a new partner for his next joint operation: Brigadier General John Pope of the Army of the Mississippi. The Confederates had fallen back 60 miles from Columbus to Island No. 10, near New Madrid, on the Mississippi. Pope prepared to attack the new position with support from Foote and his gunboats.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Riverine Warfare: The US Navy's Operations on Inland Waters

Navy Civil War Chronology (NHHC Library)

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Forts Heiman, Henry, and Donelson | American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org)

History & Culture National Park Service: Civil War Series (nps.gov)

FURTHER READING

Laver, Harry. “Learning the Art of Joint Operations: Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy.” Joint Force Quarterly 97. March 31, 2020.

Quarstein, John V. “Capture of Forts Henry and Donelson.” Mariners’ Blog. Mariners’ Museum and Park Museum. February 5, 2021.

Smith, Timothy B. Grant Invades Tennessee: The 1862 Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016.

***

NOTES

[1] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter ORA), 128 vols. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 3, Vol. 1(1899), 81.

[2] ORA, Ser. 1, Vol. 52, Pt. 2 (1898): 56.

[3] ORA, 1, 52 (Pt.2):118.

[4] Edward McCaul, To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Naval Campaign for Memphis (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 11.

[5] John McMurray Lansden, A History of the City of Cairo, Illinois (Chicago, IL: R. R. Donnelley & Sons, 1910), 130–1.

[6] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereafter ORN), 30 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), Series 1, Vol. 22 (1890), 280.

[7] ORN, 1, 22:307.

[8] ORN, 1, 22:314.

[9] ORA, 1, 4(1882):308; ORA 4:345; ORA, 1, 7(1902):73.

[10] ORA, 1, 7:74.

[11] ORN, 1, 22:314; ORN, 1, 22:524.

[12] ORA, 1, 7:126.

[13] ORA, 1,7:124.

[14] ORN, 1, 22:570; ORA, 1, 7:864; Memphis Daily Avalanche, TN, 8 Feb 1862; Memphis Daily Avalanche, 11 Feb 1862.

[15] ORA, 1, 7:154.

[16] ORA, 1, 7:155.

[17] ORA, 1, 7:125.

[18] ORN, 1, 22:585.

[19] ORN, 1, 22:550.

[20] ORN, 1, 22:618.

[21] Naval History Division, Riverine Warfare: The U.S. Navy’s Operations on Inland Waters (Washington: GPO, 1969), 25.

[22] ORN, 1, 22:618.

[23] ORN, 1, 22:614.

[24] Isham G. Harris, “Governor’s Message,” Memphis Daily Avalanche, TN, 12 March 1862, 2.

[25] ORA, 1, 7:590.

[26] ORN, 1, 22:616; ORN, 1, 22:623.

[27] ORN, 1, 22:622.

[28] ORN, 1, 22:624.

[29] ORN, 1, 22:626.

[30] ORN, 1, 22:626.

[31] The Western Flotilla remained under the control of the U.S. Army until October 1862 when it was transferred to the Navy and renamed the Mississippi River Squadron.

[32] ORN, 1, 22:640.

[33] ORN, 1, 22:632.

[34] ORN, 1, 22:635.