Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Vicksburg

Mississippi

18 April–4 July 1863

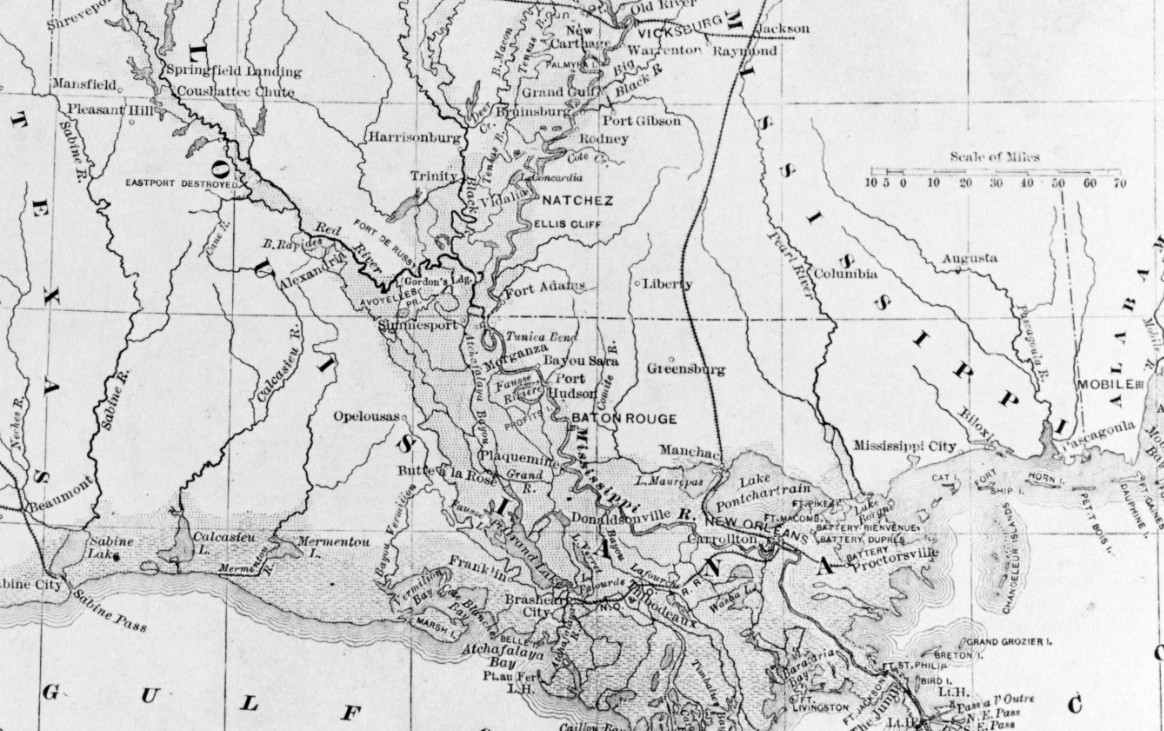

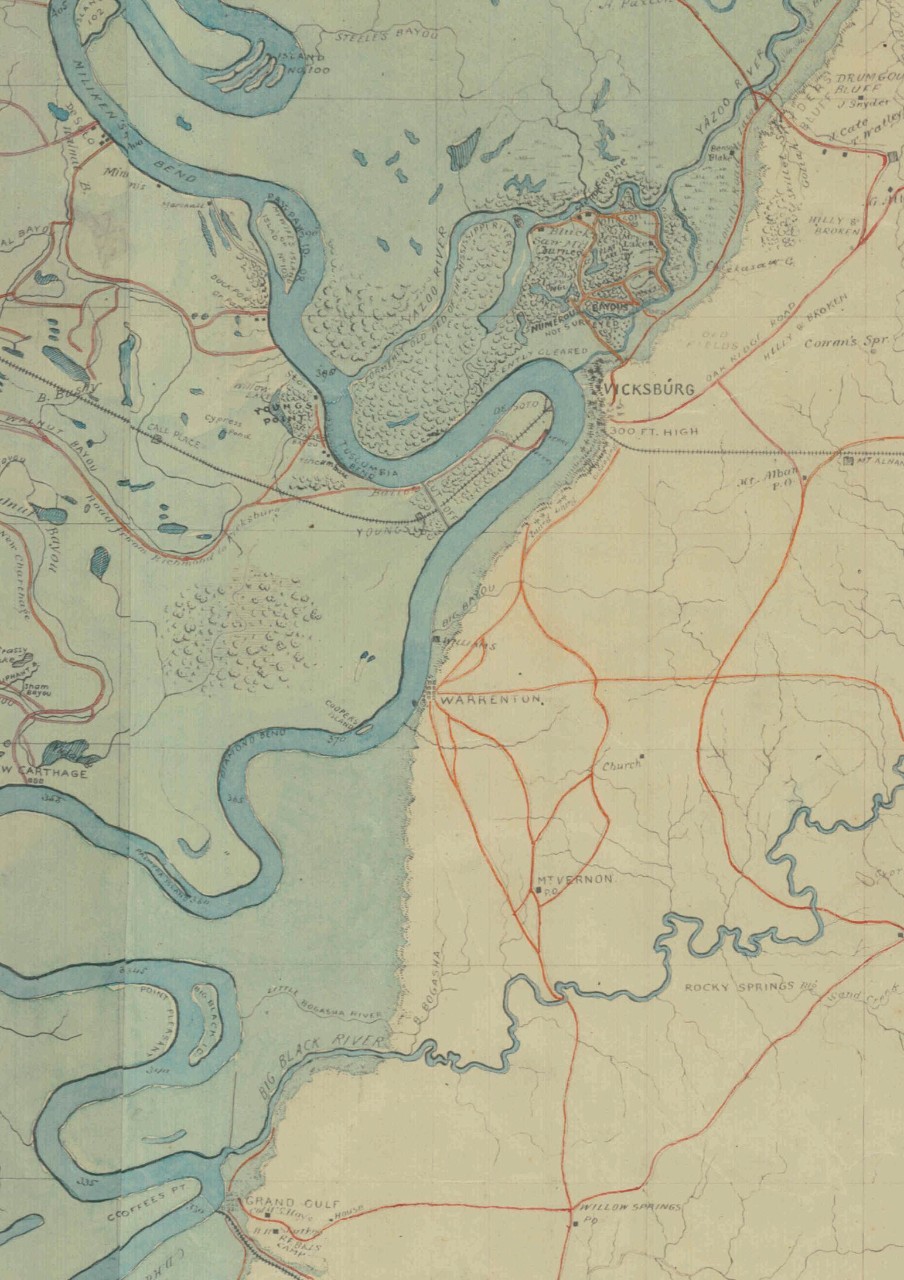

Selection from U.S. Army, Department of the Gulf, Map No. 2, New Orleans to Vicksburg, January 1863. (National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], 86455566).

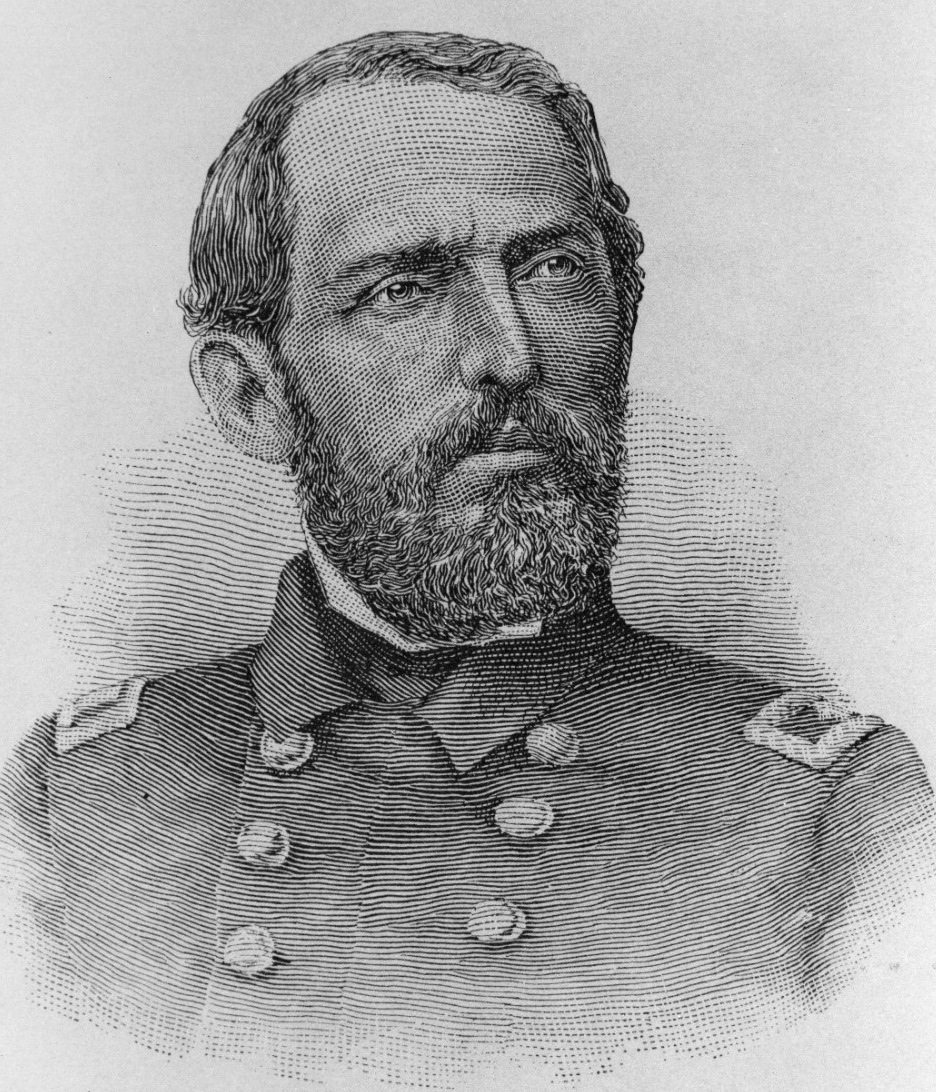

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

(Acting) Rear Admiral David D. Porter, Unites States Navy (USN)

Major General Ulysses S. Grant, United States Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, Confederate States Army

BACKGROUND

Vicksburg is situated on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River. At the beginning of the American Civil War, it was one of a series of Confederate citadels intended to ensure the Confederacy’s control of this vital supply line. In 1861, the Confederacy had no brown-water navy, nor did the United States government, but that soon began to change. The War Department provided the funding to build what became the Western Gunboat Flotilla. In 1862, its commander, Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, cooperated with Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant to launch a joint advance down the Mississippi. Their plans aligned with the national strategy, which called for the naval forces to blockade the coasts and to take control of the Mississippi River in an effort to squeeze the fight out of the rebellion.

In February 1862, Foote and Grant captured both Forts Henry and Donelson. Within days, the Confederates evacuated the city of Columbus. They fortified a new position at Island No. 10, which fell on 7 April 1862. A few weeks later, Flag Officer David Farragut and elements of his West Gulf Blockading Squadron ran past the two forts defending the mouth of the Mississippi River. On 1 May 1862, Major General Benjamin Butler and 5,000 Federal soldiers occupied the city. The capture of New Orleans left the Confederate river fortifications vulnerable on multiple fronts, with the Western Gunboat Flotilla descending to Island No. 10 and the West Gulf Blockading Squadron at New Orleans.

After allowing time to repair and resupply his vessels, Farragut seized the initiative to ascend the river. His first targets were the cities of Baton Rouge and Natchez.[1] His advance was halted at Vicksburg when the city refused to surrender.[2] After a brief reconnaissance, Farragut returned to New Orleans to resupply and prepare his fleet for riverine warfare.

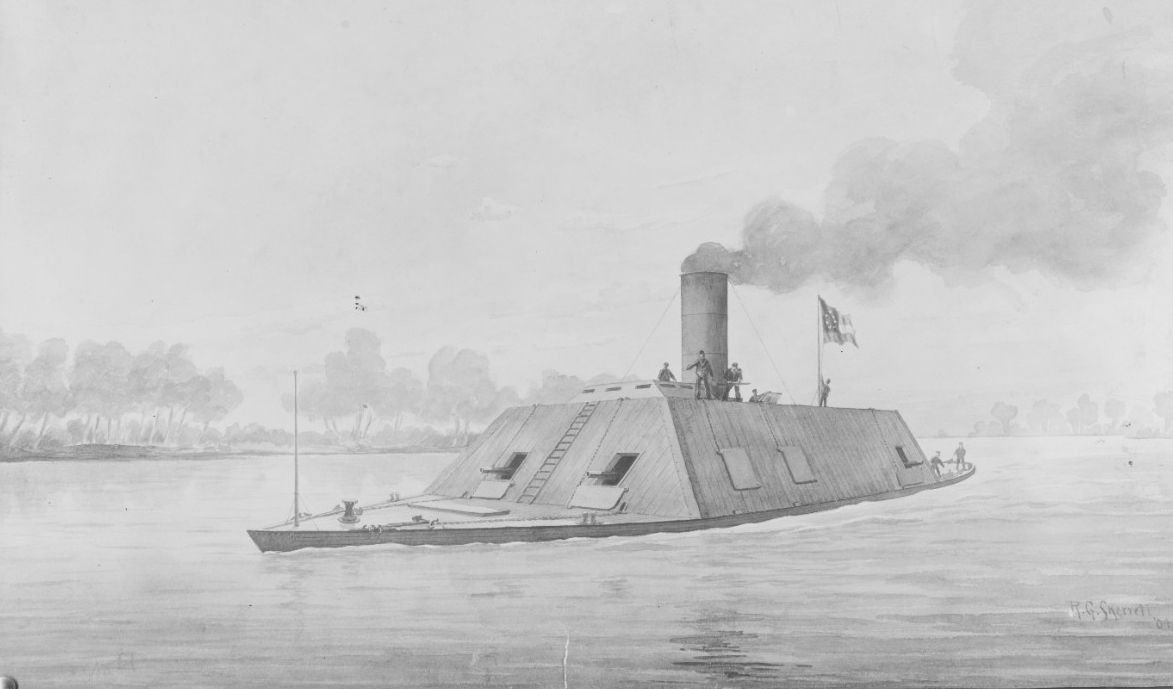

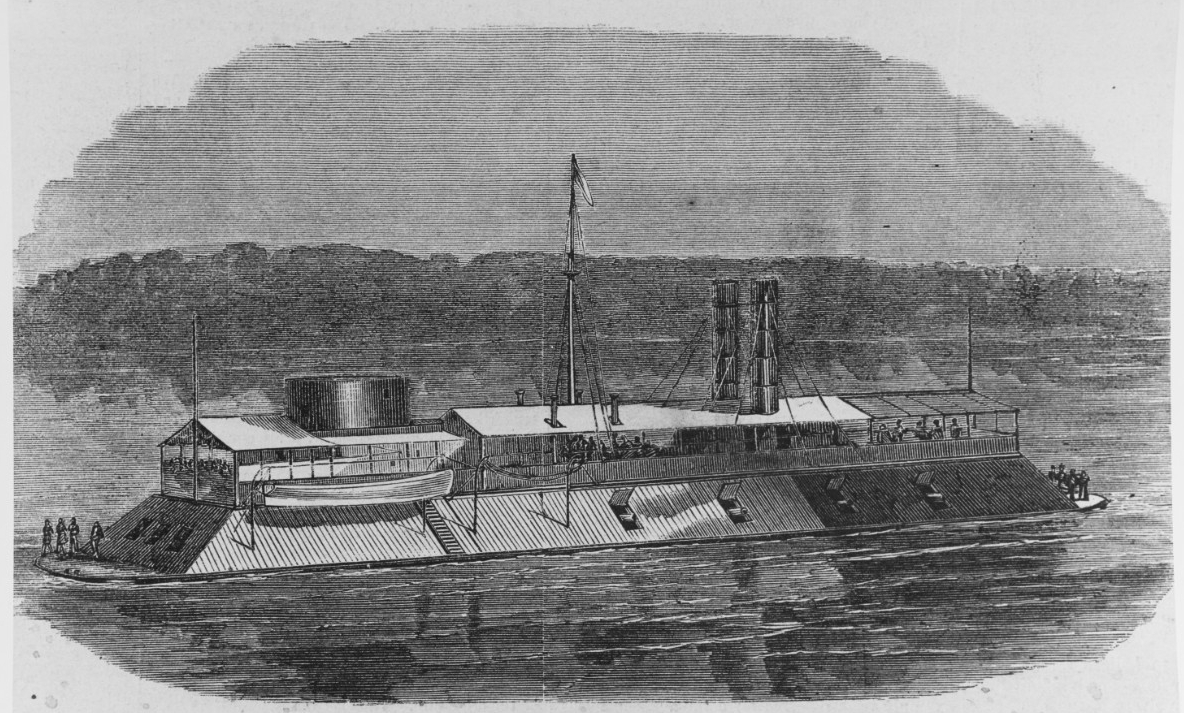

Eight vessels were all that remained of the Confederacy’s River Defense Fleet after the destruction of the vessels at New Orleans. Protecting the approach to Memphis, the small flotilla managed a minor success at Plum Point Bend on 10 May 1862 before the evacuation of Fort Pillow and their withdrawal to Memphis. This delaying action allowed time for the destruction or removal of the Confederate ironclads under construction at Memphis. The unfinished CSS Arkansas was moved to safety in a makeshift yard on the Yazoo River.

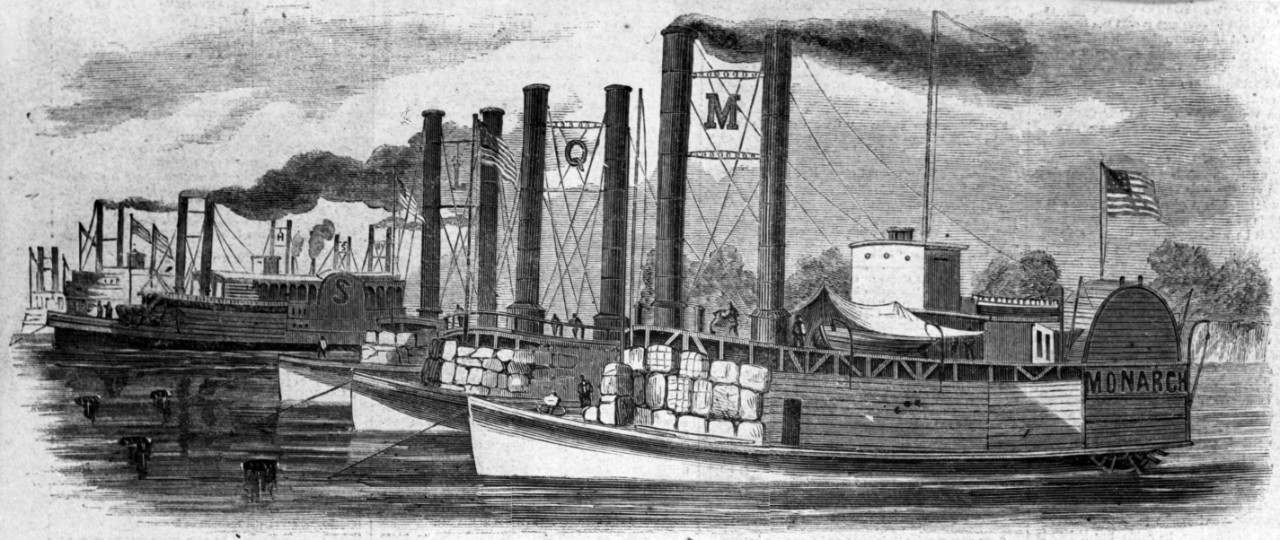

Flag Officer Charles H. Davis replaced Foote in command of the Western Gunboat Flotilla in the midst of their siege of Fort Pillow. In late May, Colonel Charles Ellet, Jr. arrived with the U.S. Army’s riverine rams under his direction. After they confirmed the Confederate evacuation of Fort Pillow, Davis and Ellet moved for a joint attack on Memphis. On 6 June, the advancing Federal flotilla destroyed most of the Confederate ships defending Memphis. A few escaped up the tributaries of the Mississippi, but the River Defense Fleet was destroyed as a unified force. Unfortunately, Charles Ellet was wounded during the battle, and he died two weeks later. His younger brother Alfred took command of the Ram Fleet. The combined U.S Army-Navy flotilla regrouped and prepared to continue their push downstream to Vicksburg.

Under pressure from the President and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, Farragut reluctantly returned to Vicksburg accompanied by Commander David Porter and his flotilla of mortar vessels. He also brought with him an army detachment of 3,000 men under command of Brigadier General Thomas Williams. This small formation had little hope of taking Vicksburg without additional support. [3] Their purpose was to occupy the city if the naval force succeeded in obtaining its surrender.

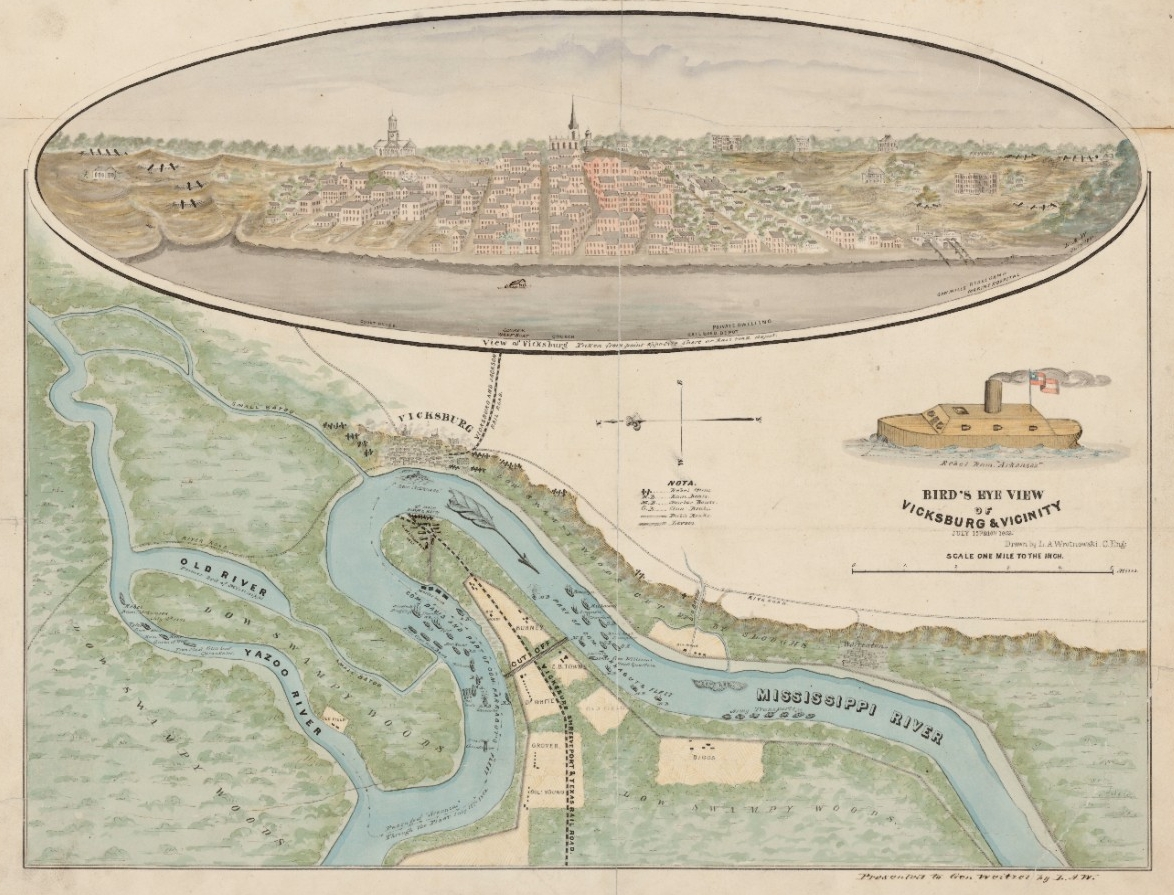

On 25 June, Ellet’s rams arrived above Vicksburg ahead of Davis’s squadron. Having learned from a local that Farragut had arrived below Vicksburg, Ellet sent a message with a party across the peninsula to make contact with the other fleet.[4] Although initially faced with suspicions, Ellet finally received orders to wait at the mouth of the Yazoo until Farragut passed Vicksburg.[5] Meanwhile, Farragut asked Davis to “come down and help [him] take Vicksburg.”[6] Farragut took eight vessels past the Confederate batteries. Meanwhile, Williams began construction of the canal across the De Soto Point peninsula opposite the city. Unfortunately, the heat, malaria, and other illnesses soon forced an end to the excavation.

Bird's Eye View of Vicksburg & Vicinity, 15–6 July 1862, drawn by L.A. Wrotnowski and C. Eng. (NARA, 102279584)

The city officials in Vicksburg had no intention of surrendering to the U.S. Navy. They had the advantage of geography. Commander Porter quickly recognized the challenge posed by the Confederate position. In his report to Welles, Porter wrote that, “ships and mortar vessels can keep full possession of the river and places near the water’s edge, but they can not crawl up hills 300 feet high.”[7] Porter recognized the difficulty of their position.

The president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, did not intend to relinquish Vicksburg without a fight. After the loss of New Orleans, he decided that a change in leadership was necesssary. He chose Major General Earl Van Dorn to command the Department of Southern Mississippi and Eastern Louisiana. Van Dorn arrived in Vicksburg in late June. He quickly sent a message to Lieutenant Isaac Brown, the man responsible for the ironclad ram still under construction on the Yazoo River.[8] Brown, in command of the unfinished Arkansas, was offended that Van Dorn should complain about delays in its construction when he was still waiting on men for his crew. He was not pleased to be hurried, replying, “I would prefer burning the Arkansas in the Yazoo River to hurling the vessel against the enemy.”[9] More than two weeks later, Brown was forced to move the unfinished ram as the water levels were dropping. Arkansas started down the Yazoo River with orders to attack the enemy fleet, run down to the Gulf of Mexico, and head toward Mobile.[10] These orders put Arkansas on a course to confront a Federal reconnaissance mission in search of the ironclad.

On 15 July 1862, Commander Henry Walke, of Carondelet, headed up the Yazoo River with Tyler and the ram Queen of the West.[11] They had not gone far when they encountered CSS Arkansas making its way out to the Mississippi. Stuck in the path of the Confederate ram, Carondelet was damaged while Tyler and Queen of the West fell back downriver. The appearance of Arkansas surprised the Federal fleet waiting above Vicksburg. [12]

Arkansas, fired upon the fleet—Lieutenant Brown was determined to cause as much damage to the enemy as possible while allowing the current to carry his failing vessel toward the protection of the batteries at Vicksburg. This act by a single vessel enraged Farragut. At the same time, his desire for retribution could not keep him in Vicksburg as the water level continued to drop. Major General Henry Halleck informed the Secretary of the War that he could not currently offer any aid to take Vicksburg.[13] On 24 July, Farragut withdrew his vessels south. Davis reluctantly withdrew north to Helena, Arkansas.

Lieutenant Brown had successfully defended Vicksburg and preserved the Confederacy’s hold on this last stretch of the Mississippi. Unfortunately, he was wounded and forced to turn over command of the ironclad. With the enemy retreating, Van Dorn ordered Brown’s replacement, Lieutenant Henry Stevens, to continue south to assist in the Confederate army’s efforts to retake Baton Rouge.[14] The ram never reached Baton Rouge. On 6 August 1862, Lieutenant Stevens was forced to scuttle the vessel after repeated engine failures left it dead in the water.[15]![]()

The destruction of Arkansas put an end to Van Dorn’s hopes of reclaiming Baton Rouge as a second stronghold on the Mississippi. Retreating from Baton Rouge, the Confederate army fortified Port Hudson below the mouth to the Red River to prevent disruption of shipping between the two rivers.

Six months into 1862, the partnership between Vicksburg and Port Hudson was all that remained to protect the Confederacy’s hold on the Mississippi River and to maintain their connection with the trans-Mississippi region of Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

PRELUDE

On 14 October, Jefferson Davis decided to replace Van Dorn with Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Van Dorn was demoted to a cavalry commander. Pemberton established his headquarters at Jackson, east of Vicksburg, to await Grant’s next move.

In October 1862, the U.S. Navy was granted control of the 15 vessels of the Western Gunboat Flotilla. It was renamed the Mississippi River Squadron and placed under the command of Admiral David D. Porter. As early as the end of October, Porter informed the Secretary of the Navy that he was ready to cooperate with the army in a move against Vicksburg.[16] Porter felt that a joint operation could result in the fall of Vicksburg if they moved quickly.[17] The new organization meant that Porter did not have to take orders from the army, but nor could he issue orders to the army. Porter was not idle while he waited. He continued to purchase vessels to be converted to gunboats. He added 54 to his squadron.[18]

In November 1862, Major General Ulysses S. Grant began advancing his first offensive toward Vicksburg. Grant first sought to move down the east side of the Mississippi River using the Mississippi Central Railroad as his supply line from the north. He planned to advance overland from Grenada to Vicksburg while Porter’s gunboats escorted transports carrying 40,000 men under Major General William T. Sherman from Helena, Arkansas, down the Mississippi River.[19] Confederate cavalry hampered Grant’s operations and prevented his advance south to join forces with Sherman. On 29 December, Sherman’s forces turned back from the Confederate defenses north of Vicksburg at Chickasaw Bayou. Grant would have to find another way forward in the spring. At the end of 1862, the United States government held the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg and south of Port Hudson. A stretch of 240 miles was still held by the Confederacy.

On 2 February 1863, Porter sent Charles Ellet aboard Queen of the West past the batteries at Vicksburg to judge the strength of their defenses. Porter was impressed by what he learned, writing to Welles that “a better system of defense was never devised.”[20] Once past Vicksburg, Ellet received orders to continue downstream and to establish a blockade of Confederate supplies from the Red River. Porter’s assessment of the city’s defenses failed to reveal any weaknesses. The batteries on the bluff and on the water were too powerful. Grant decided to initiate construction of a series of canals, first resurrecting the idea to cross the De Soto peninsula. Each attempt was intended to allow for an amphibious assault that outflanked the city’s defenses. Attempt after attempt failed as the army and Navy commanders worked through the difficulties of coordinating their assault on Vicksburg.

At the end of March, Grant finally decided it was time to change his strategy. The only way to catch Pemberton off his guard was to maneuver around Vicksburg and attack from the south. This maneuver involved coordinating a tedious march through the swamps on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River from Milliken’s Bend to New Carthage. This march had been impossible until now due to the winter flooding of the delta. Once the army arrived below Vicksburg, they would require transport to get back across the river. Grant asked Porter to escort his transports directly past the batteries at Vicksburg to rendezvous with his soldiers. At the same time, Federal cavalry provided the diversion. He was taking his men far from a supply base and into enemy territory. Grant knew that “the co-operation of the navy was absolutely essential to the success (even to the contemplation) of such an enterprise. I had no more authority to command Porter than he had to command me.”[21] In mid-April 1863, Porter’s fleet rested on the east side of the Yazoo preparing to make their run as soon as Grant’s soldiers were in position.

BATTLE

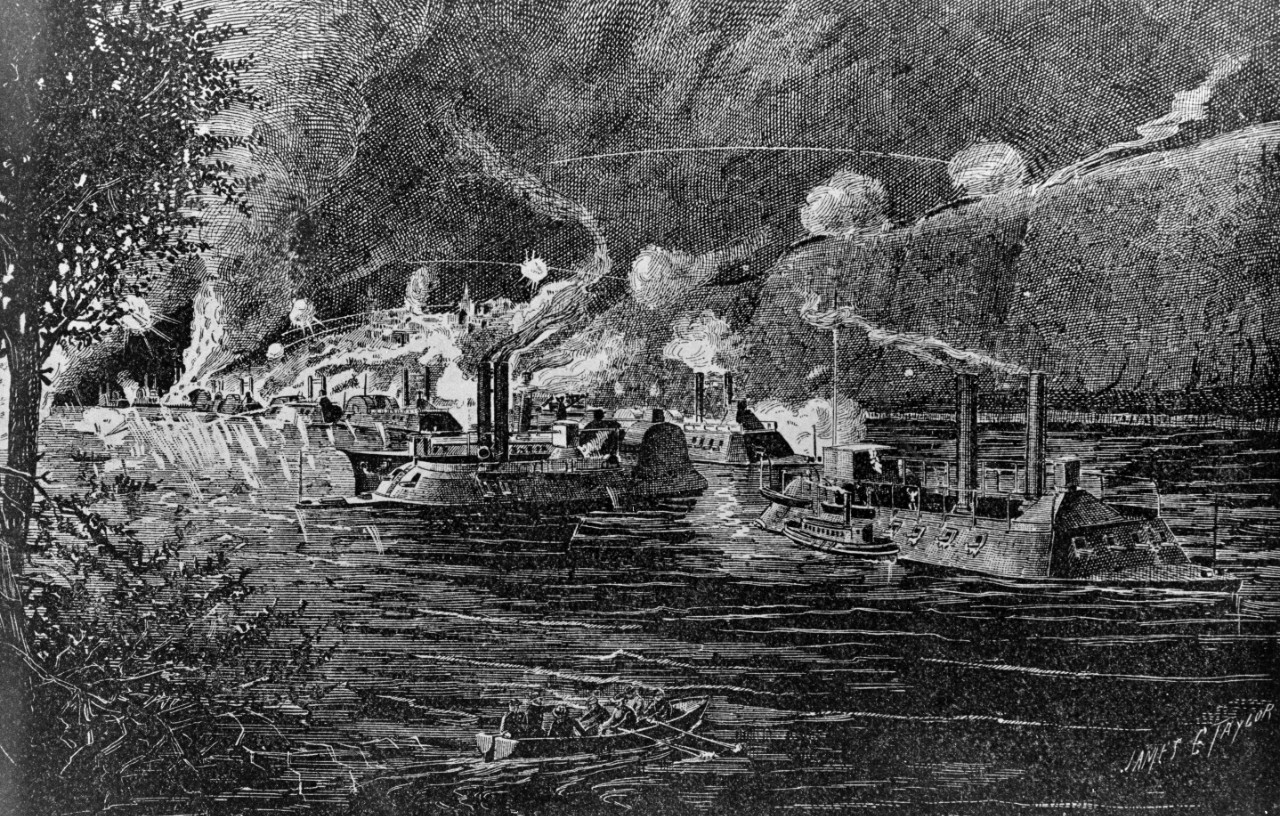

On the night of 16 April 1863, Acting Rear Admiral David Porter led his flotilla past the batteries at Vicksburg. Porter, aboard his flagship Benton, led the run followed by six gunboats–Lafayette, Louisville, Mound City, Pittsburg, Carondelet, and Tuscumbia–escorting three transports, all towing loaded coal barges. They suffered 12 casualties and only lost one army transport. Downstream, the Confederate garrison at Grand Gulf watched burning bales of cotton and fragments of boats float by them. They knew the Federal gunboats were making repairs 30 miles upriver from their position.[22]

After arriving at Grand Gulf, Porter decided to consult with Grant before launched an assault.[23] Meanwhile, the gunboats left at Grand Gulf continued to fire upon the Confederate garrison to impede them in the process of fortifying their position.

On 25 April, Porter wrote to Fox that “when the water falls, the army can march on to the city by many directions, but then we must have an army, not a skeleton of one.”[24] The need for reinforcements to prevent a drawn-out siege was dire. To prevent reinforcements from Vicksburg being sent to Grand Gulf, Grant and Porter arranged for a joint feint north of Vicksburg up the Yazoo River. Lieutenant Commander K. R. Breese was to cooperate with Sherman to distract Pemberton from Grant’s movements in the south.

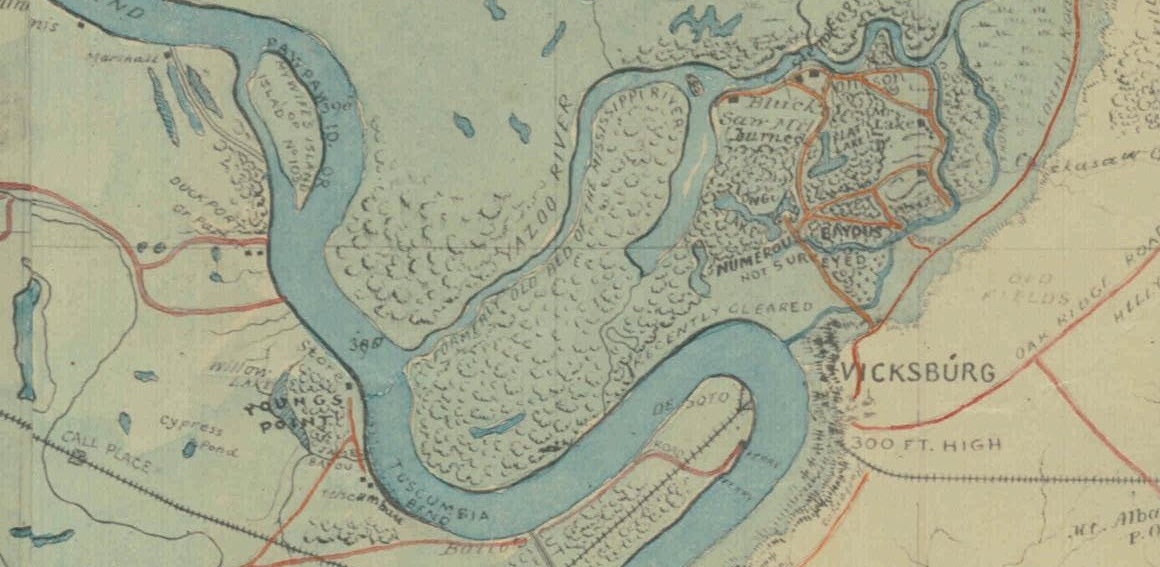

In preparation for landing Grant’s soldiers, Porter’s squadron—Benton, Lafayette, Tuscumbia, Carondelet, Louisville, Mound City, and Pittsburgh—attacked the batteries at Grand Gulf. Five hours and thirty-five minutes later, the gunboats had only achieved partial success, not enough to secure a landing.[25] Grant decided to cross the river farther south and outflank the forts at Grand Gulf. That same evening, transports ferried the soldiers across the river to a landing at a deserted plantation near the small town of Bruinsburg, Mississippi, 10 miles south of Grand Gulf and 30 miles south of Vicksburg.

U.S. Army, Department of the Gulf, Map No. 2, New Orleans to Vicksburg, January 1863. Note: Observe the town of Grand Gulf on the river south of Vicksburg. (NARA, 86455566)

The transports carried 37,000 soldiers across the Mississippi, the largest amphibious landing in U.S. history until 1942.[26] This crossing opened the way for Grant to begin his overland campaign to take Vicksburg as his soldiers marched north toward Port Gibson without a supply train. The ensuing battle at Port Gibson ended in a victory for Grant. He gained a strategic crossroads that connected his army to Grand Gulf, Vicksburg, and Jackson. Outflanked, the Confederate garrison at Grand Gulf was forced to abandon their fortifications on the river. Grant did not head straight north for Vicksburg. Moving northeast, Grant headed for the Southern Railroad connecting Vicksburg to Jackson.

Operating on the margins of Grant’s overland campaign, Porter continued to use his squadron to impede any supply lines to Vicksburg. Porter went south to join Admiral Farragut to assist in clearing the Red River.[27] When news of the defeat of the Federal army at Chancellorsville reached Porter, he expressed uncertainty about the success of Grant’s campaign.[28] After Grant secured the city of Jackson, he moved west back toward Vicksburg. Although Grant had tried to avoid a siege, his success at Champion Hill and Big Black Bridge trapped the Confederate army at Vicksburg.

On 18 May, Porter sent Breese, in command of a small flotilla—Choctaw, De Kalb, Linden, Romeo, Petrel and Forest Rose—up the Yazoo River to open communications with Grant and Sherman,[29] thus allowing Porter to continue to support their operations more effectively. After the abandonment of Haynes’ Bluff near Sherman’s position, Porter ordered the destruction of the water batteries on the bluff before pushing his gunboats further up the river to Yazoo City. They destroyed what remained of the makeshift navy yard being managed by Lieutenant Isaac Brown, the former captain of Arkansas.[30]

During each of Grant’s assaults, Porter sent gunboats to shell the city as a distraction. On 19 May, Benton, Carondelet, Mound City, and Tuscumbia, fired from just out of range of the city’s lower water batteries during Grant’s first assault. As Grant pushed in from the east, Sherman moved to the northeast while Porter’s gunboats kept up a steady rotation, moving upriver to fire and falling back downstream for more ammunition. Porter used his gunboats to “keep the people alarmed.”[31] The mortar boats worked through the nights to fire on the town toward the same goal.[32] Two assaults by Grant on 19 May and 22 May failed to break the stalemate. The siege had begun.

As Grant’s army pressed in from all side on land, Porter’s gunboats continued to harass the enemy whenever possible and to provide support to the army. He wished to prevent the erection or fortification of batteries facing the river.[33] With no Confederate naval vessels operating in the area, these batteries were the only source of contention for the gunboats. Typically, Porter kept his vessels just out of range of these powerful weapons unless requested. On 27 May, Sherman made a request for assistance. Porter ordered Cincinnati to enfilade rifle pits on the northern end of the Confederate river batteries. Sherman believed the Confederate position lacked the heavy guns to damage the ironclads. Unfortunately, Sherman’s intelligence was wrong. The artillery fire from the Confederate position sunk the ironclad. Many of the 25 sailors who died in this disaster received commendations for their bravery. Porter did not blame Sherman for his misinformation, although he regretted the loss.[34] Along the river, his gunboats continued firing in rotation upon the batteries to prevent their reinforcement.[35] Other than the loss of Cincinnati, Porter’s problems consisted of shortages of coal and ammunition.

As the weeks passed, Porter continued to suggest new tactics and willingly offered any resources that might help to break the stalemate. During a visit to the trenches with Sherman, Porter offered to mount naval guns in a shore battery.[36] Lieutenant Commander Thomas Selfridge did the work of hauling the heavy guns ashore and supervised their fire.[37] Selfridge’s success inspired Porter to set up more shore batteries. As the weeks wore on, the water level began to fall on the river. Porter kept the boats to the canal side.[38] The falling river did not threaten his riverine fleet as it had affected Farragut’s deep-draft seagoing vessels in the past summer, but that did not mean that the water level was not a concern. Frustrated with the length of this siege, Porter wrote to Welles that “if we do not get Vicksburg now, we never will.”[39] Determined to contain the enemy atop the hill, Porter kept a careful eye on any movement that suggested an escape for the besieged garrison.[40] Finally, after 47 days under siege, Pemberton surrendered the garrison on 4 July 1863.

AFTERMATH

The Federal victory at Vicksburg divided the Confederacy in two. Pemberton surrendered an army of almost 30,000 men to Grant. The concurrent Federal victory at the battle of Gettysburg boosted morale in the North. Although the fighting continued for another two years, the city’s fall was a turning point in the war. The running of the batteries at Vicksburg on 16 April 1863 was the most famous event in the the Navy’s involvement in the Vicksburg campaign. This tactic had already been successful at Fort Donelson and Island No. 10, [41] but the repetition of this success at Vicksburg did not diminish its significance. This bold move from Porter’s squadron commenced a campaign that ended in the capture of Vicksburg.

Grant had already established a history of collaborating well with the Navy during the campaign to take Forts Henry and Donelson. Grant and Porter forged a solid working relationship in the early days of the campaign against Vicksburg that carried them through the siege. In his after-action report, Porter recognized the vital role played by the Army in their investment of Vicksburg.[42] Porter knew the importance of the Army’s role in their success from his past experience at Vicksburg in July 1862. Likewise, Grant later mentioned in his memoirs, “The co-operation of the navy was absolutely essential to the success (even to the contemplation) of such an enterprise.” [43] Sherman also directly expressed his gratitude for Porter’s role.[44] The Navy’s support for Grant’s army did not stopped after Porter put Grant’s soldiers ashore at Bruinsburg. He continued to offer support to the Army throughout this campaign beyond the beachhead. The successful partnership between Grant and Porter helped to establish a new standard for future joint operations.

The fall of Vicksburg ensured the subsequent surrender at Port Hudson five days later. Farragut had not interfered with Porter’s handling of the Vicksburg campaign of 1863, nor did he remain in the Mississippi long after this the fall of the city. For his own role in their success, Porter received his permanent promotion to rear admiral.[45] He subsequently assumed command of the entire Mississippi river. This shift allowed Farragut and his Western Gulf Blockading Squadron to return to New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. In May 1864, Porter created 10 operational naval districts to manage his command.[46] He encouraged cooperation between the commanders of each district, but he ensured that no commander could give vessels to another district except in the case of an emergency.[47] The Mississippi River belonged to Porter’s squadron and he intended to keep it.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Letter, 1863

Letter on Sinking of USS Cincinnati, 1863

USS Black Hawk Engagement Report, 1863

Vicksburg Campaign, January–July 1863

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

The Vicksburg Campaign: Approaching the Bastion City, American Battlefield Trust.

The Vicksburg Campaign, November 1862–July 1863, U.S. Army.

Vicksburg National Military Park, U.S. National Park Service.

FURTHER READING

Chatelain, Neil. Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2021.

Gabel, Christopher. Staff Ride Handbook for the Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862–July 1863 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College, 2001. [PDF]

Joiner, Gary D. Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron. Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

McCaul, Edward B. To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Naval Campaign for Memphis. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2014.

Smith, Myron J. After Vicksburg: The Civil War on Western Waters, 1863–1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2021.

Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. The Civil War on the Mississippi: Union Sailors, Gunboat Captains, and the Campaign to Control the River. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2016.

***

NOTES

[1] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Vol. 18 (Washington: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1904), 579.

[2] ORN, 1, 18, 493.

[3] “Letters of General Thomas Williams, 1862,” The American Historical Review 14, no. 2 (1909): 322.

[4] ORN, 1, 23 (1910), 242.

[5] ORN, 1, 23, 243.

[6] ORN, 1, 23, 197.

[7] ORN, 1, 18, 641

[8] ORN, 1, 18, 650.

[9] ORN, 1, 18, 650.

[10] ORN, 1, 18, 652.

[11] ORN, 1, 19 (1905), 41.

[12] Edward McCaul, To Retain Command of the Mississippi: The Civil War Campaign for Memphis (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 158.

[13] United States War Department, The War Of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 17, pt. 2 (Washington: GPO, 1887), 97.

[14] ORA, 1, 15 (1886) 14.

[15] Myron J. Smith, The CSS Arkansas: A Confederate Ironclad on Western Waters (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, Inc., 2011), 277–84.

[16] ORN, 1, 17, pt. 2, 320–21.

[17] Gustavus Vasa Fox, Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Vol. 2 (New York: De Vinne Press, 1920), 141.

[18] ORN, 1, 23, 396.

[19] ORN, 1, 23, 397.

[20] Gary D. Joiner, Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron (Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007), 110.

[21]] Grant, Vol. 1, 1885, 461.

[22] ORN, 1, 24, 552–54; ORN, 1, 24, 566.

[23]ORN, 1, 24, 576.

[24] D. D. Porter to G.V. Fox, 25 April 1863, in Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Vol.2, 176.

[25] ORN, 1, 24, 610.

[26] Note: Kristopher White, of American Battlefield Trust, relates this event to “Grant’s D-Day,” cited in Chris Mackowski and Dan Welch, The Summer of ’63: Vicksburg and Tullahoma: Favorite Stories and Fresh Perspectives from the Historians at Emerging Civil War (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2021), 10.

[27] David D. Porter, The Naval History of the Civil War (New York: Sherman Publishing Company, 1886), 317.

[28] D.D. Porter to G. V. Fox, 14 May 1863, in Confidential Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox, Vol.2, 182.

[29] ORN, 1, 25, 5.

[30] ORN, 1, 25, 8.

[31] ORN, 1, 25, 18.

[32] ORN, 1, 25, 21.

[33] ORN, 1, 25, 48.

[34] ORN, 1, 25, 38–41.

[35] ORN, 1, 25, 48.

[36] ORN, 1, 25, 56.

[37] ORN, 1, 25, 57.

[38] ORN, 1, 25, 62.

[39] ORN, 1, 25, 66.

[40] ORN, 1, 25, 72.

[41] Joiner, Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron, 130.

[42] ORN, 1, 25, 103–104.

[43] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (New York: Charles L. Webster and Co., 1894), 272.

[44] ORN, 1, 25, 106.

[45] ORN, 1, 25, 111.

[46] ORN, 1, 26, 329–30.

[47] ORN, 1, 25, 335.