Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Island No. 10

Missouri

28 February–8 April 1862

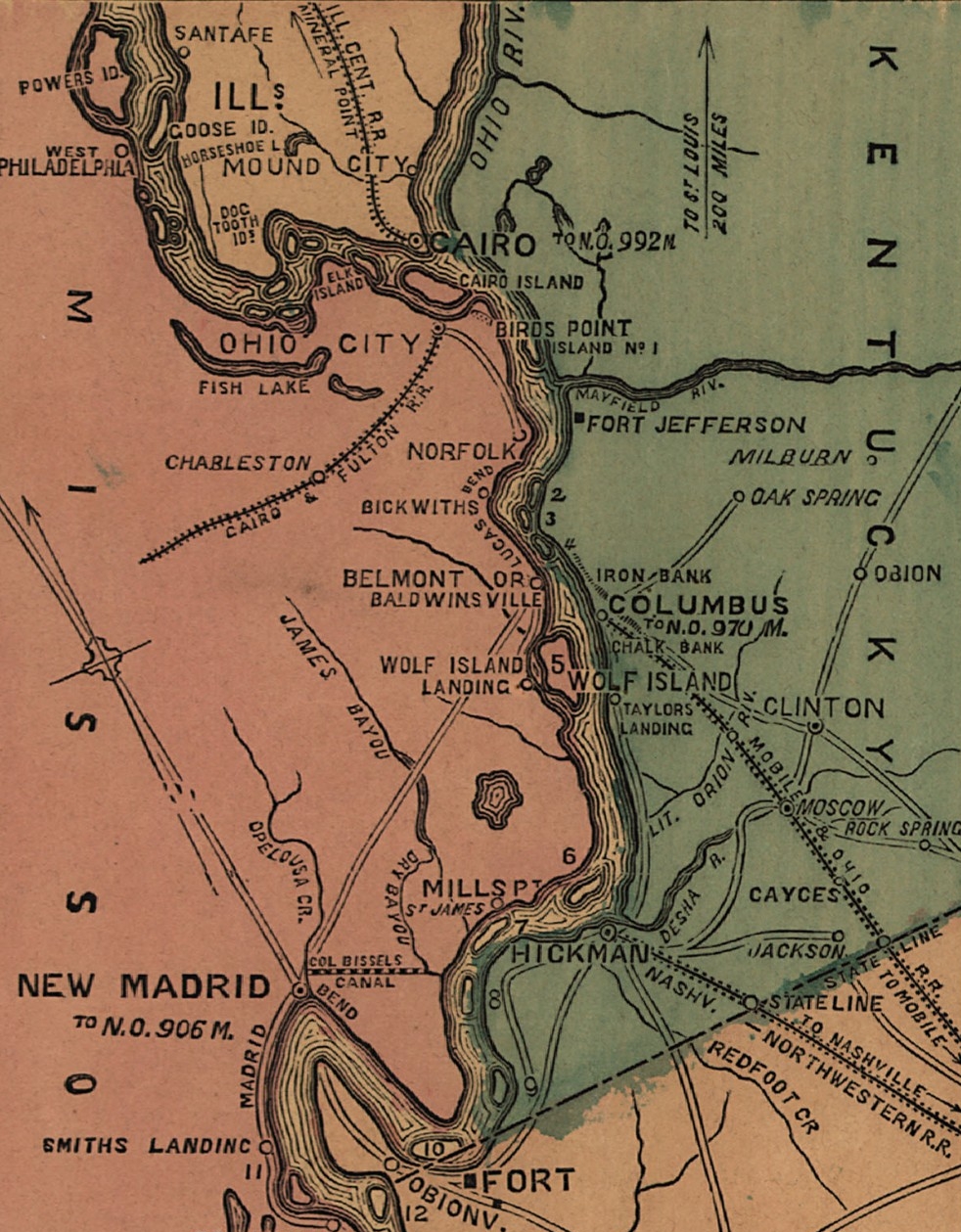

Selection from Lloyd's New Map of the Mississippi River from Cairo to its Mouth, c. 1863. (Library of Congress [LC], 99447107)

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, U.S. Navy (USN)

Brigadier General John Pope, U.S. Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Flag Officer George N. Hollins, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

Brigadier General John P. McCown, Confederate States Army (CSA)

Brigadier General William W. Mackall, CSA [1]

BACKGROUND

Island No. 10 derived its name from the fact that it was the tenth island south of the convergence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers at Cairo, Illinois. Located on an S-bend in the Mississippi River, the island was in the first bend, and the town of New Madrid rested in the second bend. The swampy lowlands on either shore of the river at this point prevented any attempt to flank the batteries on the river. The only approach to the peninsula across from the island was from the south.

In 1861, General Leonidas Polk was the Confederate commander in the western theater prior to the appointment of Albert Sidney Johnston. In August, Polk assigned Gideon Pillow, a brigadier general formerly of the provisional army of Tennessee, to the task of establishing a battery at Island No. 10 to protect river navigation below the island. Pillow anticipated briefly occupying New Madrid as a base of operations, but he was dissatisfied with its fortification.[2] On 14 August, Polk sent Captain Asa Gray, a topographical engineer, to further assess the ground.[3] In disagreement with Pillow, Gray saw the value of Island No. 10.

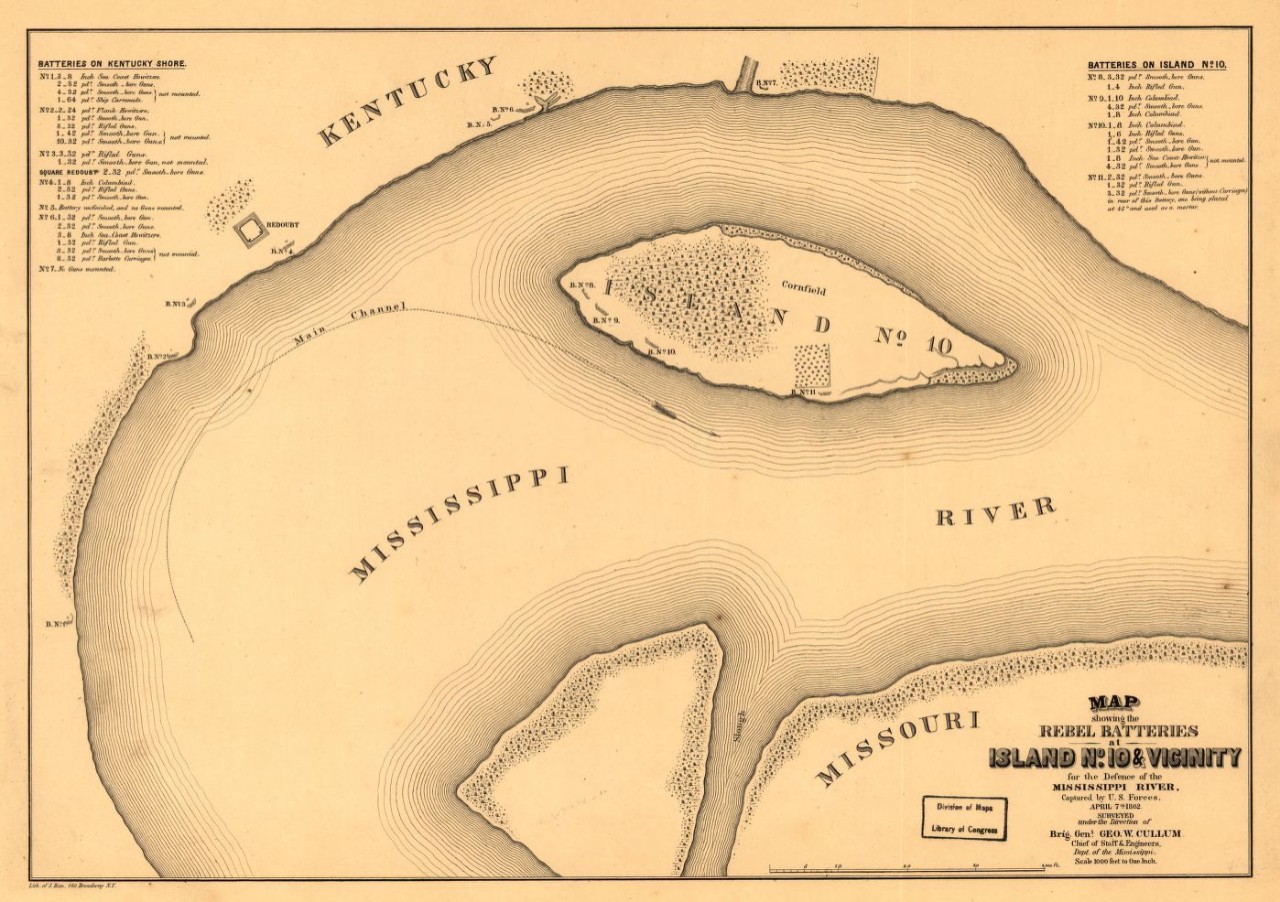

Map showing the Confederate batteries in the vicinity of Island No. 10, April 1862. (LC, 99447231)

Gray also believed Columbus, north of Madrid, was an important point for occupation and fortification, but only if the Federal forces were the first to violate Kentucky’s neutrality.[4] Without waiting for the Federal forces to make the first move, Polk gave orders for Pillow to move from New Madrid to Columbus in September, thus becoming the first to violate the state’s neutrality.[5]![]() This move frustrated Gray. He felt the absence of strong topographical features invited an enemy attack before he was prepared, even if the ground would ultimately prove unfavorable to defeat. He hoped that a Union attack would be put off until the spring.[6]

This move frustrated Gray. He felt the absence of strong topographical features invited an enemy attack before he was prepared, even if the ground would ultimately prove unfavorable to defeat. He hoped that a Union attack would be put off until the spring.[6]![]() Rising water flooding the surrounding swamplands in this season promised to strengthen the Confederate position naturally.[7] In the meantime, Gray requested more workers to hurry his preparations.[8]

Rising water flooding the surrounding swamplands in this season promised to strengthen the Confederate position naturally.[7] In the meantime, Gray requested more workers to hurry his preparations.[8]

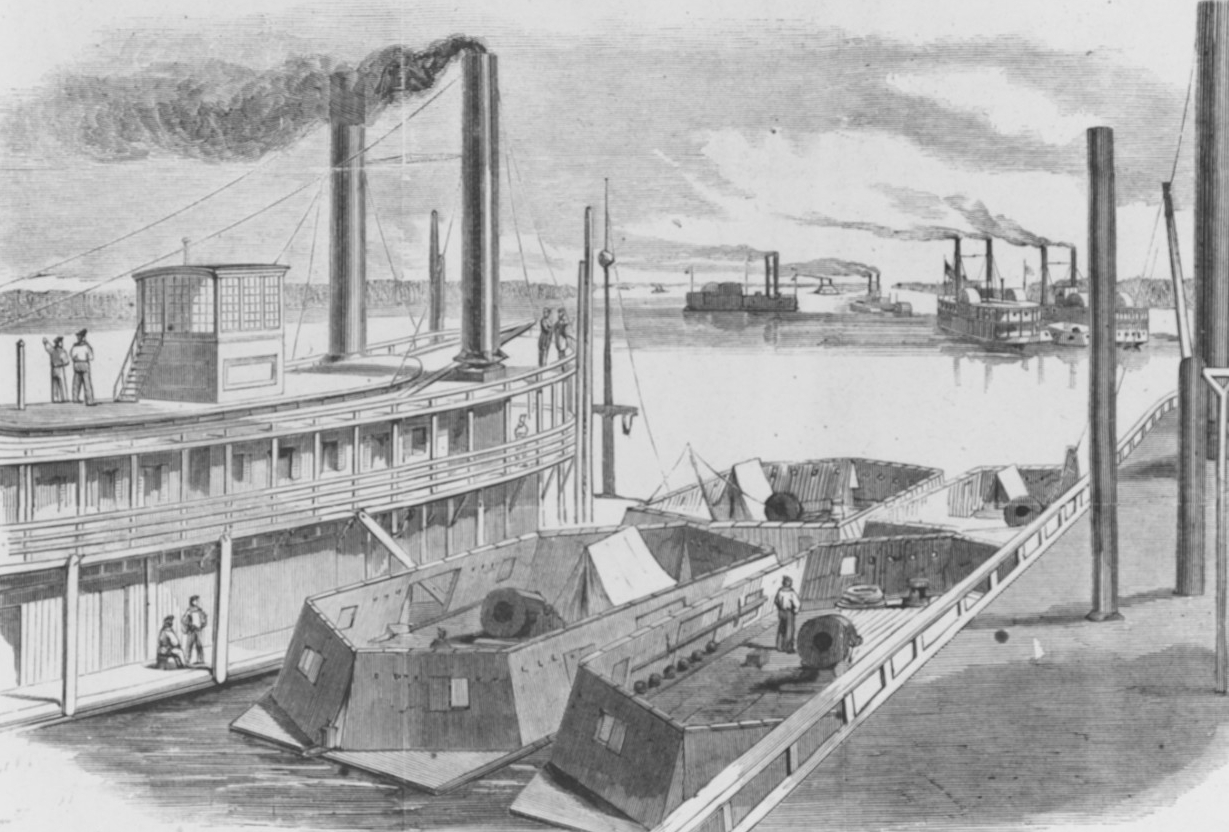

While the Confederate army was braced to defend the Mississippi River from the north, their navy prepared the defenses at the mouth of the river. Flag Officer George N. Hollins, CSN, was in charge of the Confederate vessels at New Orleans.[9] At the start of war, neither side had naval units on the Mississippi River, but the Federals had spent months building a force that included ironclad gunboats. Hollins and the rest of the Confederate navy were focused on the blockade and the defense of the major coastal cities rather than inland waterways. It seemed as if the Confederate forts along the Mississippi River would be sufficient to retain control of its navigation south of Cairo. Pillow and Polk made repeated requests for armed vessels to support their positions.[10] They were less and less confident in their position as they continued to receive the news of the expanding Union flotilla based at Cairo.

Keeping control of the Mississippi River was too important to continue to ignore the developing situation at Cairo. Between November 1861 and January 1862, Hollins dispatched five wooden gunboats to Columbus: General Polk, McRae, Ivy, Livingston, and Jackson.[11] The floating battery New Orleans arrived at Columbus in December. Pontchartrain and Maurepas joined the fleet in February and March.[12] None of these vessels had the firepower to launch an offensive, but they did provide reassurance to Polk and his staff against their fear of the enemy ironclad gunboats that patrolled the river between Columbus and Cairo.

PRELUDE

The U.S. Army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla, under the command of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, forced the surrender of the Confederate garrison at Fort Henry in less than a day. The damage inflicted on his ironclad flagship Essex did little to diminish the success of the flotilla’s first exchange of blows with the enemy. On 14 February, Foote arrived at Fort Donelson with six gunboats, four of them ironclad. This joint operation proved more challenging than the conquest of Fort Henry for the small riverine force, but no less successful.

Following the surrender of Fort Donelson, Foote returned to Cairo to repair his vessels. Although Foote himself was injured in the foot during the bombardment of the second fort, he left Cairo on crutches almost as soon as he arrived. Both Foote and his Army counterpart, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, hoped to strike Nashville. To their disappointment, Major General Henry Halleck, in command of all Federal armies in the West, dictated that the gunboats go no farther on the Cumberland River than Clarksville, Tennessee.[13] Nashville was within the district boundaries of the Army of the Ohio under General Don Carlos Buell. Whether due to Halleck’s own jealousy of Grant’s success or his reluctance to give aid to his district rival for command in the West, Halleck delayed Foote’s advance to Nashville. This delay allowed the Confederates the time they needed to withdraw with their supplies.

While he waited, Foote wrote to his wife of his frustration with the army. He no longer wished to “obey any orders except the Secretary’s and President’s.”[14] Halleck allowed the Confederates to make a slow withdrawal from Nashville and turned back to the Mississippi River, ordering Foote to lead an armed reconnaissance down the river to Columbus, Kentucky.[15] Foote affirmed for Halleck that the Confederates still held the town and showed no sign yet of moving their batteries. With this knowledge, Halleck finally sent Foote’s gunboats to Nashville, only to rescind his order upon hearing that the town had been abandoned. [16] With Nashville now emptied of troops and supplies, it was not a difficult conquest.

Still on crutches, Foote prepared for the campaign down the Mississippi River with caution. He received regular messages from both Major General George B. McClellan, the current general-in-chief of all Union armies, and from Halleck to get his gunboats into position immediately. However, Foote refused to be pressured into a new campaign against a fortified position after his experience at Fort Donelson. The possession of Clarksville and Nashville presented little danger to his gunboats; the Confederate fortifications on the Mississippi River were far more risky.

In the aftermath of the events at Forts Henry and Donelson, General Albert S. Johnston, in command of the Confederate forces in the Western Theater, made the difficult decision to withdraw his forces from Tennessee and Kentucky. Despite rumors printed in the newspapers that Hollins’ gunboats were en route to purge the rivers of the enemy, there were no plans to take the gunboats beyond Columbus.[17] General Pierre G. T. Beauregard had recently superseded Polk in command of the Confederate forces in the Upper Mississippi River Valley. Beauregard supported a withdrawal from Columbus and ordered Polk into motion. Polk was reluctant to cede his position, but Beauregard had Johnston’s support.

As the Confederate army prepared its withdrawal to Island No. 10, the Confederate navy sent more vessels upriver. On 19 February, Stephen Mallory, the Confederate secretary of the navy, sent a telegram to Hollins, then at New Orleans. Mallory ordered Hollins to travel himself to Memphis, and then on to Columbus if no other orders interceded his movement.[18] A small squadron of Confederate gunboats and the floating battery New Orleans had been anchored at Columbus since December. Hollins was concerned about taking more vessels away from New Orleans, feeling that the situation in Columbus was a trap and that he was leaving the port city vulnerable.[19] On 1 March, Columbus was evacuated.

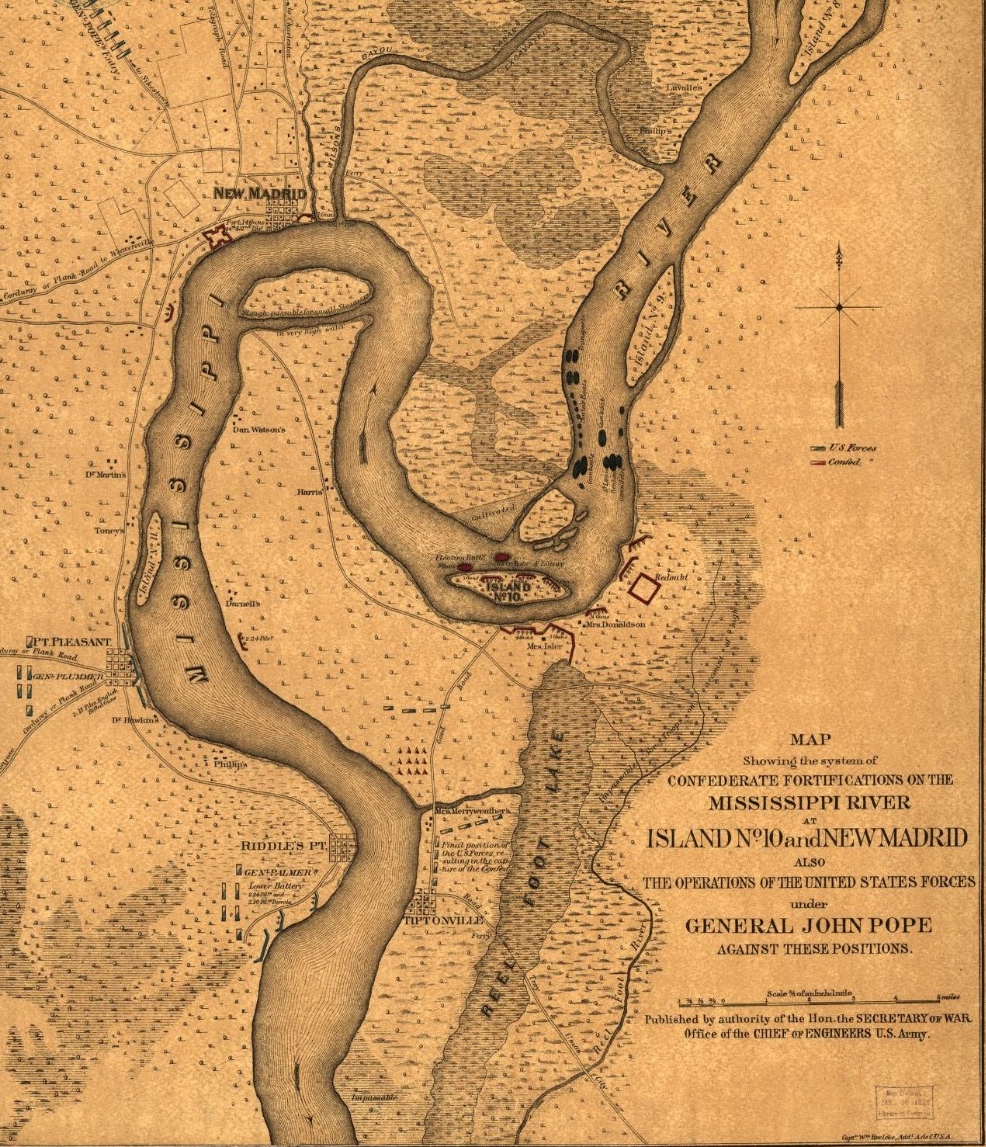

Map of the Mississippi River at Island No. 10 and New Madrid, c. 1862. Note the marked location of the floating battery below Island No. 10. (LC, 99447230)

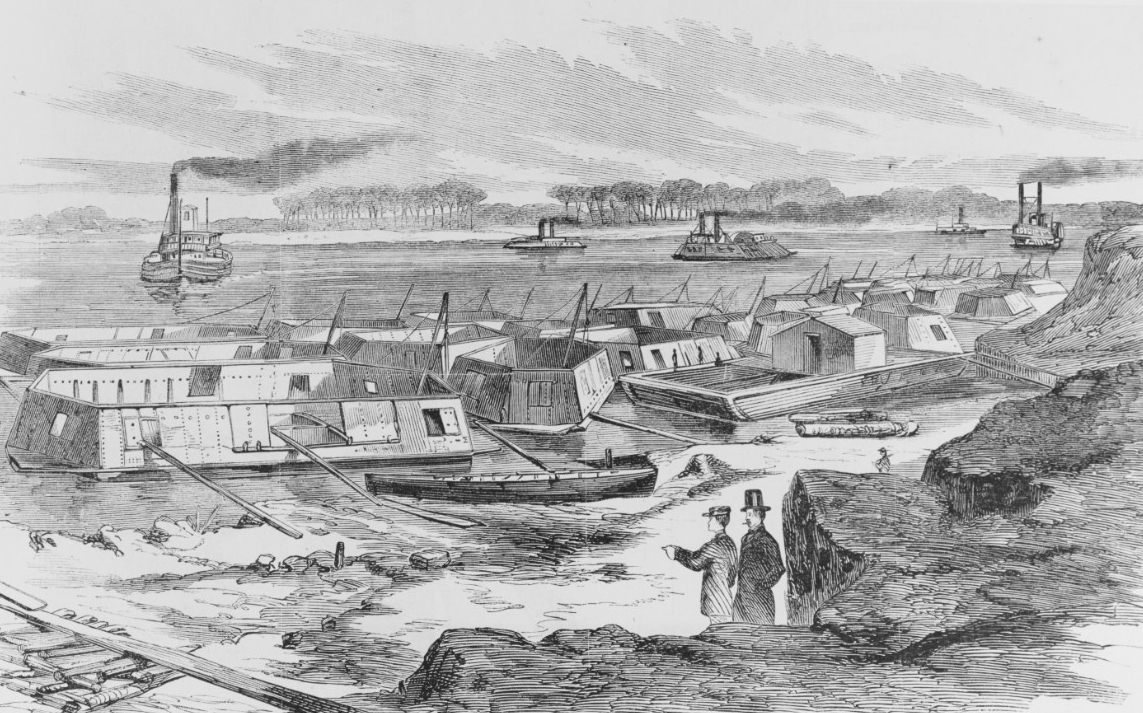

The floating battery was subsequently moved down from Columbus to Island No. 10.[20] Polk was confident that even if New Madrid had to be abandoned, his forces could hold the island with support from the Tennessee side, and, therefore, keep control of the river. On 3 March, Foote arrived in Columbus with a small flotilla to find the town emptied of troops and munitions. The Confederate forces had reestablished a new line of defense further south on the Mississippi at Island No. 10 and New Madrid. Polk withdrew even farther south to Jackson, Tennessee. Foote traveled back to Cairo to prepare for the next move and to coordinate with Halleck’s appointee to the new Army of the Mississippi. Halleck selected Brigadier General John Pope to command this new army and ordered him to clear all enemy obstacles along the upper Mississippi River Valley.

The Confederate evacuation of Columbus necessitated the expansion of the defenses at Island No. 10. Polk assigned Brigadier General John P. McCown to New Madrid on 25 February 1862. McCown brought his division of 5,000 men with him as reinforcements. With the 2,000 already assigned to the garrison, his numbers averaged 7,000. He began strengthening the unfinished works.[21] Flag Officer Hollins provided more reinforcements with five gunboats, four of which were at New Madrid and another at Madrid Bend. Unfortunately, the gunboats were all wooden, and Hollins understood their ineffectiveness against ironclad vessels. On land, McCown lacked the numbers to do more than defend his position.[22] Reinforced and ready, the Confederate army and navy forces at New Madrid waited for the Federals to take the offensive.

BATTLE

The natural barriers provided by the spring floods forced the Federals to march overland 50 miles to attack New Madrid from the west. On muddy roads in the midst of winter, this march was difficult but not impossible. On 28 February, Pope and his soldiers departed Commerce, Missouri. Upon his departure, he made a request to Halleck for gun and mortar boats to move to Columbus in preparation for his attack on New Madrid.[23] After four days of trudging through the mud, Pope settled into camp on the outskirts of New Madrid. Out of range of the enemy guns, he assessed the Confederate fortifications. The strength of their fortifications and the four gunboats on the river behind them gave him pause. Pope made the decision to send for heavy artillery and more troops rather than risk open assault.

Halleck relayed Pope’s requests for gunboats to Foote, but Foote refused to move his gunboats into position. Foote subsequently wrote to Gideon Welles, the Secretary of Navy. He was frustrated with the pressure being applied by the Army. He felt his force was not adequately prepared for this campaign.[24] Unwilling to accept Foote’s reasoning, Halleck reiterated the necessity of making an “immediate demonstration at Island No. 10, and, if possible, assist General Pope at New Madrid.”[25] With each passing day, Halleck became more impatient. As the days passed, Foote continued to assert his independence and delay his departure for Columbus.

On 10 March, Halleck wrote to his chief of staff in Cairo to send the siege guns to Pope. In the same letter, he begged the question, “Why can’t Commodore Foote move to-morrow? It is all important. By delay he spoils all my plans.”[26] On the same day, Foote finally declared that he would be ready in two days with the proviso that he needed more soldiers “to occupy after we have taken Island No. 10 and New Madrid.”[27] The siege guns arrived from Cairo on 13 March. Pope advised Captain J.A. Mower, in charge of the guns, to concentrate fire on the gunboats and the enemy’s floating battery.[28] Pope had little ammunition for his new guns, which forced him to repeat his request for gunboats.[29] However, Pope was surprised the next morning when the enemy had fled across the river.[30] Hollins’ fleet had ferried the retreating Confederate infantry across the river before putting down anchor downstream near Tiptonville.[31] Both sides claimed about 50 killed or wounded in this 15-day siege.[32]

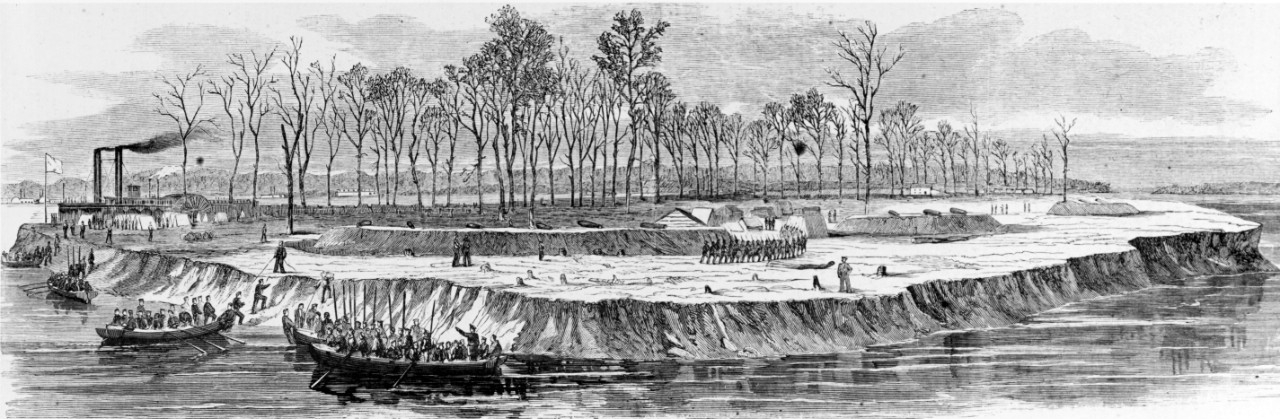

This small victory did not solve the problem of Island No. 10 for the Federals. Although Pope had gained ownership of the town of New Madrid, the battery at Island No. 10 and those across the river remained engaged. The Federal gunboats could not outflank the batteries and the army could not push farther south without control of the river.

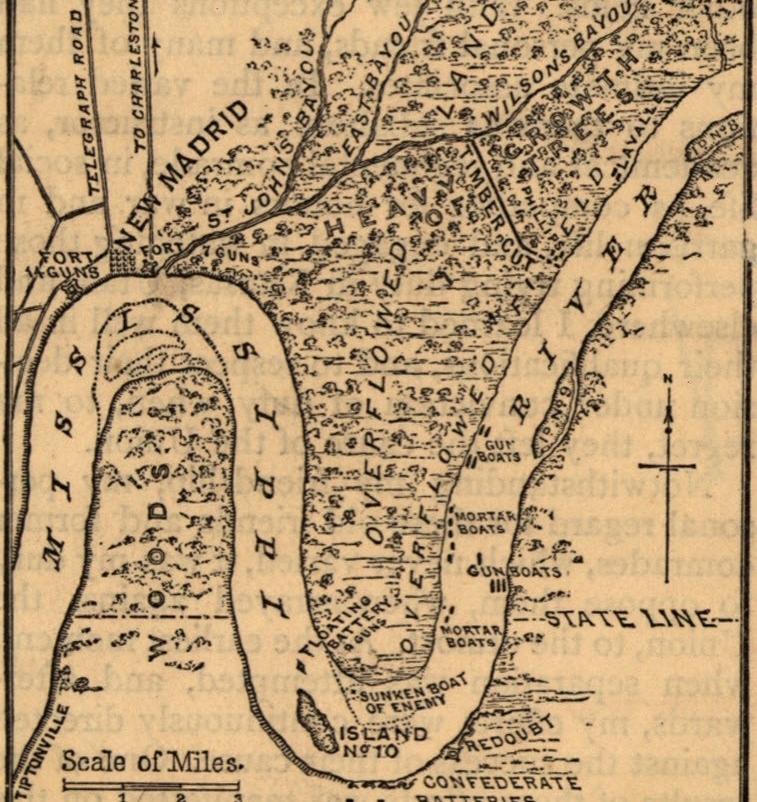

Map showing the Confederate fortifications along the river in the vicinity of Island No. 10 and the U.S. Army position at New Madrid. (LC, 99447227)

On 15 March, Foote approached Island No. 10. He began his bombardment of the island and its batteries with his mortar boats. Foote’s flotilla included seven ironclad gunboats and ten mortar boats. Each boat carried a heavy 13-inch seacoast mortar on a vertical pivot. However, these vessels were unwieldly and required tugs to move them. Although each mortar could fire a 200-pound shell a little over two miles, the bends of the Mississippi River would make it difficult to employ this heavy ordnance to its full effect. Foote was reluctant to engage the gunboats and risk damage like what he had seen at Fort Donelson. Halleck had the idea of establishing a heavy battery on the shoreline in an effort to bolster the efforts of the flotilla, but Pope did not have the guns necessary to fire across the river. Therefore, Pope and his subordinates came up with the idea to build a canal through the swamps to bring the transports that would allow them to ferry their force across the river.[33]

A few days into the Federal naval bombardment at Island No. 10, the Confederate high command decided to make some changes. Although they had lost New Madrid, Beauregard and Polk were convinced that the island was secure.[34] Johnston was calling for reinforcements, and Beauregard and Polk chose to send McCown and replace him in his command of the remaining forces near Madrid Bend. Brigadier General William W. Mackall took over from McCown on 31 March 1862.[35] Mackall’s biggest concern for his new command was the morale of his troops. He believed his position was secure until the river began to drop in late spring.[36] Hollins’ fleet remained at anchor near Tiptonville, resupplying the garrison on the island by night. Mackall and his superiors underestimated Pope’s determination to cross the river and the courage of the captain of the ironclad Carondelet.

The Federal engineers completed the 12 miles of canal in 19 days. The finished passage allowed for the draft of steamboats and barges, but not gunboats. Meanwhile, Pope never ceased to pressure Foote to run his ironclads past the island. Finally, Commander Henry Walke, captain of Carondelet, volunteered for the mission after a meeting on 29 March. On 4 April, Walke made his run with a volunteer crew under the cover of darkness. Two days later, Lieutenant Commander Egbert Thompson and the crew of Pittsburg made the same run on a stormy night. Four transport steamers were brought through the newly constructed canal on the night of 6 April. The presence of the gunboats and the threat of Pope’s soldiers crossing the river below Island No. 10 forced Mackall to withdraw farther inland. Retreating overland and cut off below on the river, the Confederates sank the gunboat Grampus and six other transports to prevent them falling into enemy hands.[37] On 7 April, two Confederate officers surrendered the isolated river battery at Island No. 10 to Foote.[38] On 8 April, Mackall surrendered the remaining forces near Tiptonville.

AFTERMATH

The loss of New Madrid and Island No. 10 left only Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River between Foote’s flotilla and Memphis. The Federal victory at Island No. 10 earned John Pope the title of major general and new orders to report back east. Although Pope gave little credit to Foote in his after-action reports, neither the flag officer’s role nor the courage of Captain Walke went unnoticed.[39] Foote and his flotilla pressed on to Fort Pillow with Pope and his transports. However, Pope did not linger at Fort Pillow. Halleck ordered him to Pittsburg Landing to join the march on Corinth in the aftermath of the Battle of Shiloh Church on 6֪–7 April 1862. Foote was left alone to continue the campaign to gain control of the Mississippi River. After Pope’s departure, Foote lacked the infantry to take the fort or to continue the campaign to strike Memphis. Foote’s injury to his foot continued to plague him. In early May, he soon put in for a leave of absence to seek treatment. He intended to return, but he never did resume command of his flotilla.

In the aftermath of this Confederate defeat at Island No. 10, Commodore Hollins seemed more determined than ever to avoid a face-to-face confrontation with the Federal ironclads. He rejected the instructions of Secretary Mallory to “strike a blow when and where you can." Hollins protested that he could do nothing against the ironclad gunboats of the enemy.[40]

The reluctance by Hollins to face the ironclads prompted General Beauregard to suggest that the guns be removed from Hollins’ gunboats as the wooden gunboats were “very frail in comparison with those of the enemy, and would not, I apprehend, endure a long encounter with them.”[41] Hollins left his fleet to return to New Orleans after receiving news of the appearance of the enemy there. He later faced a court of inquiry for his actions. Despite Hollins’ own reluctance to contend with the ironclads, the Confederate River Defense Fleet attacked the Federal squadron at Fort Pillow on 10 May 1862 before retreating to Memphis. The Confederate navy continued to impede the Federal forces on the Mississippi River until their last stand at Memphis in June 1862.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Riverine Warfare: The US Navy's Operations on Inland Waters

Navy Civil War Chronology (NHHC Library)

Island #10 Campaign, March–April 1862

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Gunboats on the Mississippi, American Battlefield Trust

Unvexed Waters: Mississippi River Squadron, Part 2, Emerging Civil War.

FURTHER READING

Daniel, Larry J., and Lynn N. Bock. Island No. 10: Struggle for the Mississippi Valley. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1996.

Tomblin, Barbara. The Civil War on the Mississippi: Union Sailors, Gunboat Captains, and the Campaign to Control the River. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2017.

Bowery, Charles R., Jr. The Civil War in the Western Theater, 1862. The U.S. Army Campaigns of the Civil War. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2014 [PDF].

***

NOTES

[1] Mackall replaced McCown on 31 March 1862 in command of the Confederate forces in the vicinity of Island No. 10.

[2] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 3 (Washington: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1881), 630 (hereafter cited as ORA).

[3] ORA, 1, 3, 651.

[4] ORA, 1, 3, 687.

[5] ORA, 1, 4 (1882), 188.

[6] ORA, 1, 3, 703; ORA, 1, 8 (1883), 141.

[7] ORA, 1, 8, 142.

[8] ORA, 1, 3, 705.

[9] ORA, 1, 3, 708.

[10]ORA, 1, 3, 739; U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Vol. 22 (Washington: (GPO, 1908), 794 (hereafter cited as ORN).

[11] ORN, 1, 22, 845; for further reading on this journey, see Neil P. Chatelain, Fought Like Devils: The Confederate Gunboat McRae (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2014).

[12] Myron J. Smith,Timberclads in the Civil War: the Lexington, Conestoga and Tyler on the Western Waters (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013), 179.

[13] ORN, 1, 22, 616; ORN, 1, 22, 623.

[14] ORN, 1, 22, 626.

[15] ORN, 1, 22, 626.

[16] ORN, 1, 22, 635.

[17] Clarksville Chronicle, 14 February 1862; Evening Bulletin (Charlotte, NC), 21 February 1862.

[18] ORN, 1, 22, 824.

[19] ORN, 1, 22, 824.

[20] ORN, 1, 22, 832.

[21] ORA, 1, 8, 125–26.

[22] ORN, 1, 22, 831.

[23] ORA, 1, 8, 570.

[24] ORN, 1, 22, 652.

[25] ORN, 1, 22, 656.

[26] ORN, 1, 22, 664.

[27] ORN, 1, 22, 665.

[28] John Pope, edited by Peter Cozzens, Robert I. Girardi, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 49–50; ORA, 1, 8, 614; ORN, 1, 22, 754.

[29] ORA, 1, 8, 612.

[30] ORA, 1, 8, 613.

[31] ORN, 2, 1 (1921), 798.

[32] ORA, 1, 8, 614.

[33] Pope, 51–52.

[34] Neil P. Chatelain, Defending the Arteries of the Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020), 110.

[35] ORA, 1, 8, 133.

[36] ORA, 1, 8, 809.

[37] ORA, 1, 8, 78.

[38] ORN, 1, 22, 720.

[39] ORN, 1, 22, 728–35.

[40] ORN, 1, 22, 839.

[41] ORN, 1, 23 (1910), 698.