Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On May 16, 1919, three U.S. Navy Curtiss NC seaplanes attempted to take off for the initial leg of the first transatlantic flight from Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, to the Azores. At 1,200 miles, it was the longest leg of the journey, and it was estimated to take about 15 hours. However, although NC-4 was able to get airborne, NC-1 and NC-3 could not get off the bay’s surface, and NC-4 had to return to the Canadian island. After weight and balance shifting on NC-1 and NC-3, all three aircraft were finally able to get in the air later that day. In anticipation of the historic flight, 22 Navy ships were strategically stationed along the preplanned route at approximately 50-nautical-mile intervals, poised to engage searchlights and fire pyrotechnics to assist the seaplanes during the night portion of the flight. Initially, the seaplanes flew in formation, but as night fell, only NC-4’s running lights worked, so Cmdr. John H. Towers, overall commander of the flight, ordered the seaplanes dispersed to avoid the risk of an airborne collision.

As daylight broke the following day, the seaplanes ran into heavy fog banks that made navigation extremely dangerous, as the pilots found it difficult to find the horizon and maintain a level flight. Although the seaplanes were equipped with the latest navigation equipment, they were essentially lost in the fog. As it became increasingly hazardous to continue flying, NC-1 and NC-3 were forced to land in the open ocean. Both aircraft suffered enough damage that further flight was deemed impossible. The crews were subsequently rescued by ships in the vicinity of their landings. The lone NC-4, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read, at one point went into a spin in the fog, but luckily was able to get a glimpse of the sun and managed to pull out. The aircraft reached the Azores later that day.

On May 20, NC-4 took off for Lisbon, Portugal, but had to turn back about 150 nautical miles out due to mechanical problems. After receiving repairs, the seaplane took off again on May 27, flying over 13 U.S. Navy ships before landing on the Tagus River at Lisbon that evening. The second leg of the trip took 9 hours and 43 minutes, with NC-4 thus becoming the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic (Charles A. Lindbergh’s flight in 1927 was the first nonstop transatlantic flight). On May 31, NC-4 flew from Lisbon to Plymouth, England, but mechanical problems once again plagued the flight. The crew had to make two stops en route before NC-4 finally arrived at Plymouth, becoming the first aircraft to fly from the United States to England. Huge crowds, a 21-gun salute from a British warship, and an escort by the Royal Air Force met NC-4 as it flew into British airspace. Once on the ground, the crew of NC-4 met the crews of NC-1 and NC-3 in London, received decorations from King George V, and then traveled to Paris, where they met with President Woodrow Wilson, who was negotiating the Versailles Treaty that formally ended World War I. After all the pomp and circumstance, NC-4 was dismantled and shipped back to the United States. Upon their return stateside, the three crews embarked on a goodwill tour of the East and Gulf Coasts. Read, the flight commander of NC-4, was awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, and the entire crew of NC-4 received the Navy Cross. Towers was awarded the Navy Cross for leading the mission.

For a brief period, NC-4 was displayed in New York’s Central Park before it was donated to the Smithsonian in 1920. Only the hull was displayed by the Smithsonian, as the museum did not have a space large enough to fit the massive seaplane. In anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the flight, N-4 went through an extensive restoration, and it was displayed on the National Mall in Washington, DC, for the anniversary. In 1974, the Smithsonian donated NC-4 back to the Navy, and it’s currently on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. For more naval aviation firsts, visit NHHC’s website.

Vietnam War@50: Mayaguez Incident

On April 17, 1975, Khmer Rouge guerillas defeated Cambodian government forces and captured that country’s capital. With the defeat of South Vietnam and fall of Saigon less than two weeks later, Southeast Asia was now dominated by Communist movements. In May 1975, a brief but violent engagement took place between the United States and Khmer Rouge fighters. The incident stemmed from a hostage situation that involved a U.S.-registered container ship and its crew. It was to be the final combat action of the Vietnam War.

On May 12, 1975, a Khmer Rouge patrol boat approached container ship Mayaguez near the uninhabited Cambodian island of Poulo Wai. The patrol boat forced Mayaguez to stop via warning shots, including one from a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Khmer Rouge fighters then boarded the American vessel, claiming the ship was in Cambodian waters. At the time, the United States and Khmer Rouge used different interpretations of the extent of territorial waters. Claiming that Mayaguez had violated Cambodian waters, the Khmer Rouge vessel seized the American ship and took its captain and 39 crewmembers hostage. Distress signals were sent from Mayaguez before the crew was detained, and an initial report on the situation reached Washington, DC, by that afternoon.

The next day, U.S. Navy P-3 reconnaissance aircraft located Mayaguez, which had been moved to Koh Tang, an island around 30 miles from the Cambodian mainland. Plans for a rescue operation were immediately put into motion, and Koh Tang was put under continuous aerial surveillance. After Khmer Rouge patrol boats fired on U.S. reconnaissance aircraft, the boats were sunk in retaliation. Then, a two-pronged rescue operation was developed: U.S. Marine units would board Mayaguez with support from frigate USS Harold E. Holt (DE-1074), while a separate U.S. Marine detachment, transported by U.S. Air Force CH-53 and HH-53 helicopters, would assault Koh Tang. Both actions would begin early on the morning of May 15.

On the day of the operation, Marines boarded Mayaguez very easily. However, the Marines quickly discovered that Mayaguez was completely abandoned and took possession of the ship. Attention shifted to landing operations on Koh Tang, where Khmer Rouge resistance was proving to be much stiffer than anticipated. Estimates ranged between 200–300 enemy combatants. Three of the five helicopters in the initial U.S. landing were shot down, with two crashing on the northeastern beach of the island and one crashing into the ocean around a mile offshore. By the time the first assault wave had landed, the majority of participating U.S. helicopters had been destroyed or disabled. However, more than 130 Marines and a handful of Air Force personnel had been successfully landed on Koh Tang. Around three hours after the operation began, the Mayaguez hostages’ situation shifted dramatically. A fishing boat waving a white flag approached Koh Tang and was intercepted by destroyer USS Henry B. Wilson (DDG-7). Aboard the fishing boat was the crew of Mayaguez. The ship’s captain reported that Khmer Rouge fighters had moved them to another island the previous day, briefly interrogated them, and then freed them. The crew’s captors hoped that this would encourage the United States to call off bombing sorties on ports and naval bases on the Cambodian mainland, which had begun that morning as well.

With Mayaguez recovered and under tow, and the ship’s crew safely back on their ship, U.S. operations shifted toward the successful extraction of all military personnel on Koh Tang. This initially required the insertion of more Marines to stabilize the situation on the ground, particularly because the U.S. landing force on the island was split into three separate groups. Additional helicopter-delivered reinforcements resulted in a total of around 230 Americans on the island, enough to maintain a defensive perimeter while withdrawals were underway. Helicopters began to extract the Marines during the afternoon and throughout the evening while facing heavy enemy fire as the perimeter continued to shrink with each successful extraction. Darkness also complicated operations, but the last Marines were reportedly picked up from Koh Tang just after 8 p.m. During the operation, 41 U.S. service members were killed in action: 25 Air Force pilots, aircrew, and security force personnel; 14 Marines; and 2 Navy corpsmen. Of the casualties, 23 Air Force personnel were lost in a helicopter crash in Thailand in preparation for the operation, and the remaining 18 service members lost their lives on and around the island of Koh Tang. The final 41 names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, represent those lost in the Mayaguez incident.

McCann Rescue Chamber

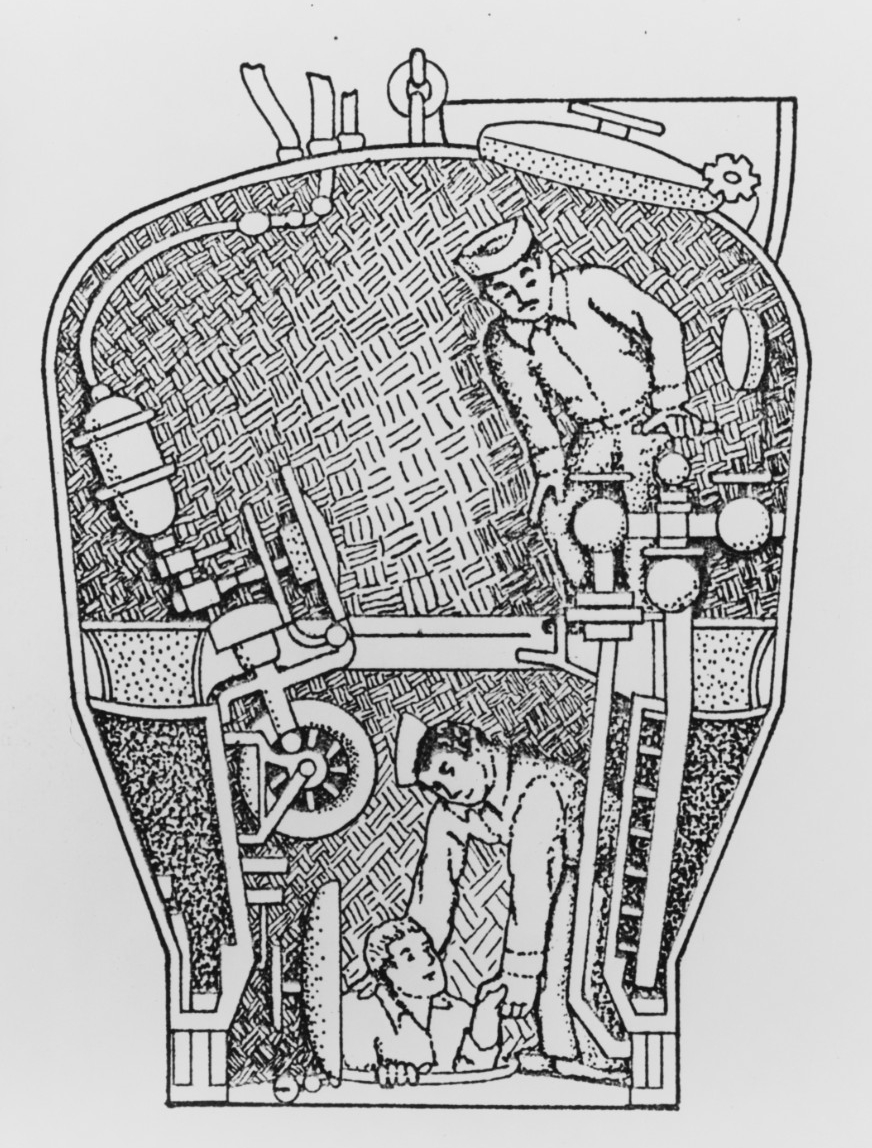

On May 24–25, 1939, Vice Adm. Allan R. McCann’s rescue chamber became the first deep-water device that was used to save crewmembers on a sunken submarine. On May 23, 1939, USS Squalus (SS-192) flooded and sank off Portsmouth, New Hampshire, after a main engine air-induction valve was left open. Twenty-six of its crew, trapped in the flooded aft compartments, drowned; however, 33 managed to survive in the forward part of the submarine. Lt. Cmdr. Charles Momsen, the initial designer of the chamber, led the rescue effort during four submersions to retrieve all the survivors successfully from a depth of 243 feet. Four Navy divers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic actions during the rescue.

Under Momsen’s direction, the Bureau of Construction and Repair had begun developing the rescue chamber in 1928. After extensive testing and experimenting, Momsen was reassigned within the bureau to design an underwater breathing apparatus for submarine escape—which became known as the Momsen lung, his most famous invention. The bureau placed then–Lt. Cmdr. McCann in charge of the design revisions Momsen had planned for the rescue chamber. McCann directed the development of the chamber for a year and a half; once completed in 1930, the bell was introduced by the Navy as the McCann rescue chamber. The chamber worked by coupling with a submarine’s escape hatch. The lower compartment of the chamber was cleared of water by blowing it into the chamber’s ballast tanks. Once the pressurized air in the lower chamber was released into the upper compartment and vented to the surface, the chamber and submarine are at equal pressure. The submarine’s escape hatch could be opened, and the trapped submariners could enter the rescue chamber for transport to the surface.

The loss of USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963 and USS Scorpion (SSN-589) in 1968 in extremely deep water—without the possibility of rescue—caused the Navy to completely rethink submarine design, maintenance, and operations to reduce the number of unrecoverable submarine accidents. This would lead to the Submarine Safety Program, an ongoing quality-assurance effort by Sailors and contractors to ensure the safety of the submarine fleet, covering everything from welds to operating procedures. For decades, the Navy has invested in developing and maintaining the ability to locate and rescue crews of downed submarines. Today, the Undersea Rescue Command (URC) is home to the Navy’s submarine rescue specialists. URC provides operational, administrative, maintenance, and logistical oversight of the Navy's shallow- and deep-water rescue systems as well as the remotely operated vehicle intervention system. URC uses a combination of active duty Sailors, Reserve personnel, and government contractors to provide worldwide submarine rescue coverage for United States and foreign submarines. URC is the sole U.S. provider for submarine rescues for the Navy.

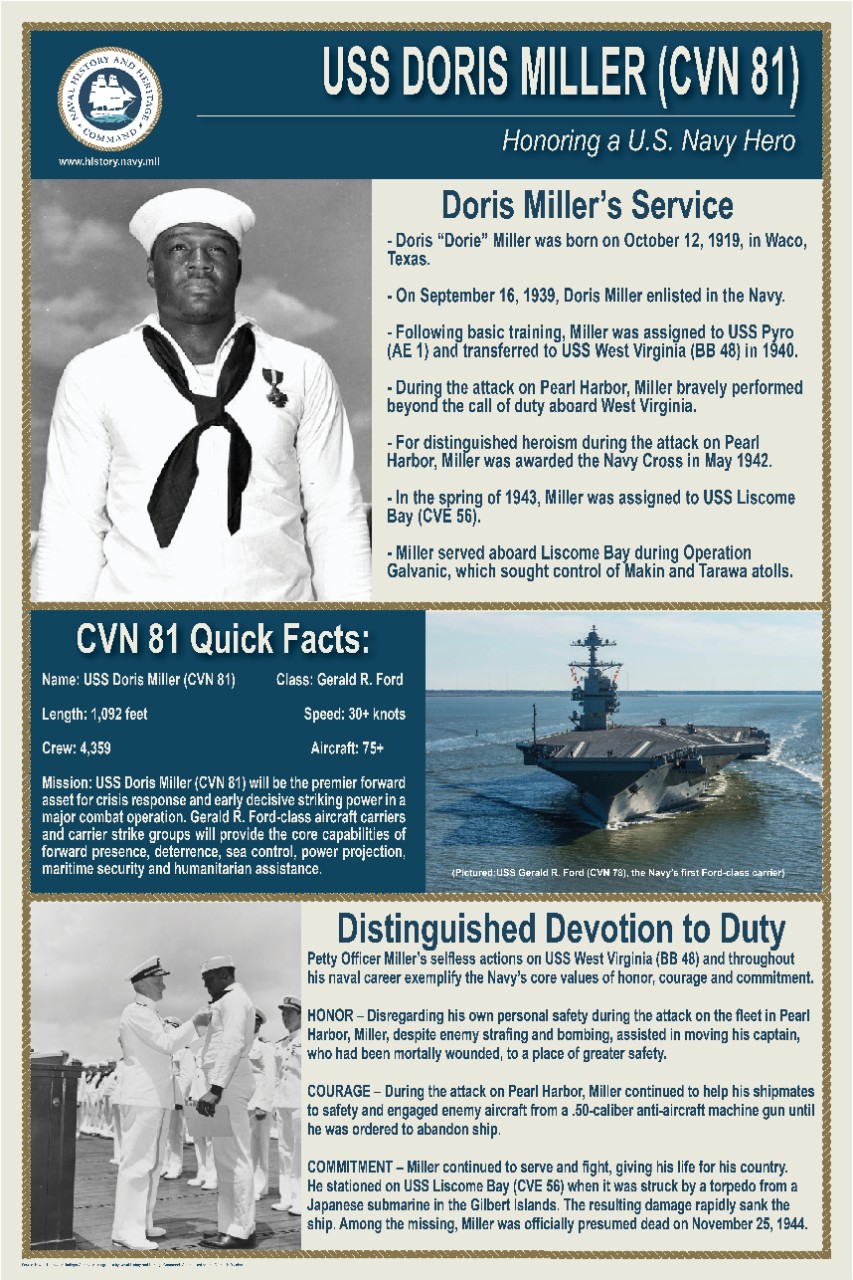

Miller Receives Navy Cross

On May 27, 1942, Mess Attendant Second Class Doris Miller, known as “Dorie” to his shipmates and friends, was awarded the Navy Cross for his acts of heroism during the Pearl Harbor attack. He was the first African American to be so honored. Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, presented the medal to Miller during a ceremony on board USS Enterprise (CV-6). “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, and I'm sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts,” said Nimitz.

Born in Waco, Texas, on Oct. 12, 1919, Miller was one of four brothers, all children of sharecroppers Henrietta and Conery Miller. When he was a teenager, Miller enrolled at A. J. Moore High School in Waco and during his extracurricular activities and support for the school became its star fullback on the football team. As a child of subsistence farmers, he was forced to drop out of school to work the family farm. In addition, he supplemented the family income by working as a cook in a small restaurant. On Sept. 16, 1939, less than a month before he turned 20 years old, Miller enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a mess attendant third class to “see the world” and earn money for his family. Following training at Naval Training Station Norfolk, Virginia, Miller was assigned to ammunition ship USS Pyro (AE-1), on which he served as a mess attendant and, on Jan. 2, 1940, was transferred to USS West Virginia (BB-48), where he became the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion due to his physical prowess.

Just before 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, Miller was collecting laundry when the first bombs of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor blasted the anchored West Virginia. When general quarters was sounded, he headed for his assigned battle station only to discover that torpedo damage had destroyed it. He then went on deck and was ordered to carry wounded fellow Sailors to safety. Next, he was ordered to the bridge to aid the mortally wounded captain of the ship. Miller subsequently manned a .50-caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine gun, which he was not trained for, until it ran out of ammunition. (At the time, African American Sailors serving in the segregated steward’s branch of the Navy were not given gunnery training.) He was later ordered to abandon ship. Miller told Navy officials he believed he had hit one of the attacking Japanese aircraft, but it was never actually confirmed due to the volume of fire from ships and shore. During the attack, West Virginia suffered 130 killed and 52 wounded. The ship was eventually repaired and served in the Pacific theater through the end of World War II.

Following Christmas leave in 1942, when he saw his home and family in Waco for the last time, Miller first reported to USS Indianapolis (CA-35) and then reported for duty aboard the newly constructed escort carrier USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56) in the spring of 1943. While serving on the ship, he participated in Operation Galvanic, the seizure of the Makin and Tarawa atolls in the Gilbert Islands. On Nov. 24, 1943, during the operation, Liscome Bay was torpedoed and sunk by Japanese submarine I-175. Miller was among the 644 crewmembers that were killed (272 of the ship’s crew were rescued).

In addition to the Navy Cross, Miller was awarded the Purple Heart, American Defense Service Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. Named in his honor, USS Miller (DE/FF-1091) was commissioned on June 30, 1973, and served until it was decommissioned in 1995. The Navy’s newest Gerald R. Ford–class aircraft carrier, USS Doris Miller (CVN-81), still under construction, will be the only aircraft carrier named for an enlisted Sailor and the first named for an African American.