Note: NHHC will not publish Navy History Matters on Dec. 27, 2022. We will resume our biweekly compilation of naval history on Jan. 10, 2023. Happy Holidays!

Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

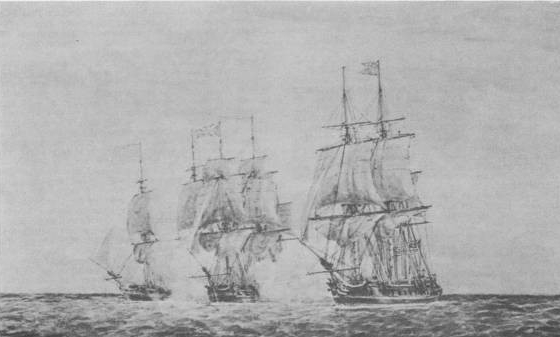

On Dec. 13, 1775, the Continental Congress approved the construction of five ships of 32 guns, five ships of 28 guns, and three ships of 24 guns at an estimated cost of $866,666. The first 13 frigates authorized to be built were Hancock, Randolph, Raleigh, Warren, Washington, Congress, Effingham, Providence, Trumbull, Virginia, Boston, Delaware, and Montgomery. The approval for the construction of the ships came after news arrived that King George III had refused the “Olive Branch Petition” (Congress’s final effort for peace with England) and that he had declared the colonies to be in a state of open rebellion. In addition to the commitment of building the new ships, Congress passed a series of resolutions to strengthen American naval forces. They included the purchase of more ships, allocation of funds to the naval committee, mobilization of American marines, approval of naval rules and regulations modeled after the Royal Navy’s Articles of War, and authorization to capture or destroy all British vessels involved in the suppression of the colonies’ budding revolution.

The petition to strengthen the Continental Navy had been gaining momentum for months leading up to the authorization of the 13 frigates. On Aug. 26, the assembly of the colony of Rhode Island sent delegates to Philadelphia to request that “a fleet of sufficient force for the protection of these colonies” be established. Although Congress had in the past urged individual colonies to mount their own defenses, the Rhode Island delegates made the case that securing American ports and waters would be more than any one colony could accomplish and Congress agreed. On Oct. 13, an advisory committee was created and staffed by John Langdon of New Hampshire, Silas Deane of Connecticut, and John Adams of Massachusetts. In addition to protecting American trade from British blockade and intimidation, the committee made the recommendation to intercept British ships loaded with supplies for enemy troops already in North America. Congress approved and directed that Massachusetts supply Gen. George Washington, then stationed at Massachusetts, with an armed schooner and a sloop for the purpose of seizing British supply ships. At the same time, Connecticut and Rhode Island would arm merchant vessels to patrol for British transports. These small actions found—surprisingly—immediate success against the powerful Royal Navy. On their heels, Congress committed to naval expansion in three key ways: by purchasing four more ships of war, expanding the naval committee to seven participants, and extending a naval force from the south of New England all the way to Georgia.

Over the course of the American Revolution, the Continental Navy sent to sea more than 50 armed vessels of various types. These seized enemy supplies and carried correspondence and diplomats to Europe, returning with needed munitions. They took nearly 200 British vessels as prizes, some off the coast of the British Isles themselves, contributing to the demoralization of the enemy and forcing the British to divert warships to protect convoys and trade routes. Of note, the threat of raids conducted on British coastal towns by Capt. John Paul Jones kept the British public on edge.

After the colonies had gained their independence, the Continental Navy was deemed irrelevant and decommissioned. The Articles of Confederation, which were implemented in 1781 and bound the former colonies into a loose arrangement of sovereign states, did not provide sufficient central government taxation powers for anything as expensive as building ships and maintaining a navy. The impact on American merchant shipping by Barbary pirates and by strained diplomatic relations with Great Britain and France soon became apparent. However, it would not be until 1794 that the United States would begin to reestablish the U.S. Navy.

Great White Fleet Began Global Cruise

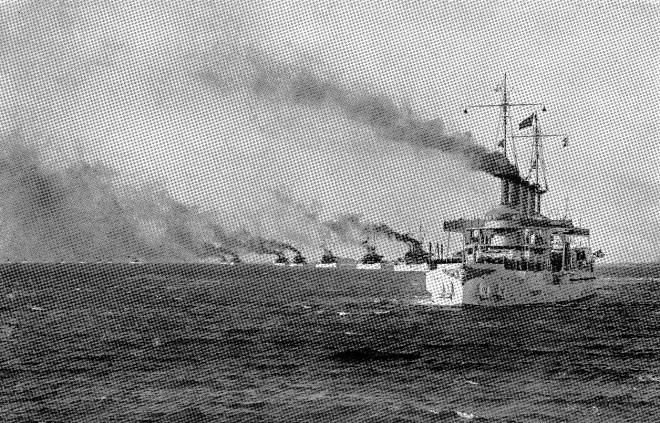

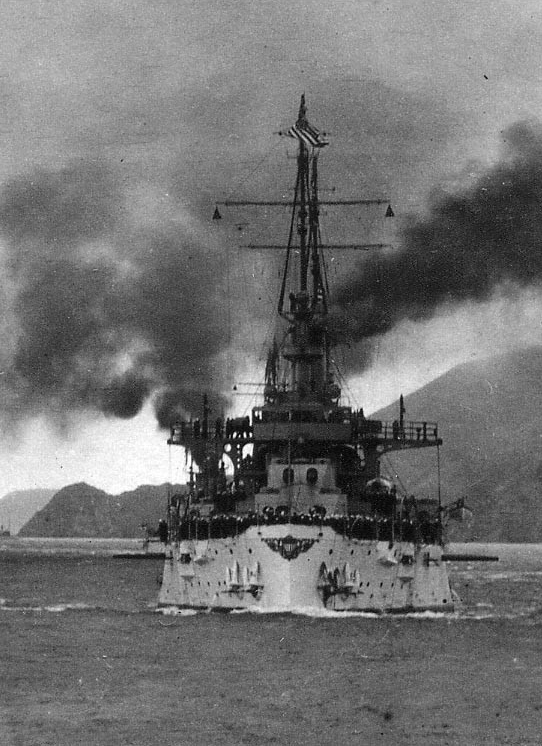

On a warm, cloudy morning on Dec. 16, 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, a force of 16 battleships bristling with guns and painted sparkling white, departed Hampton Roads, Virginia, to begin what would become a 43,000-mile, 14-month circumnavigation of the globe. The four-mile-long armada’s world tour included 20 port calls on six continents. Fourteen thousand Sailors and Marines participated in the three-leg voyage, leaving a lasting legacy at home and abroad. It was widely considered one of the greatest peacetime achievements of the U.S. Navy, and it made Roosevelt’s message clear: “America is a respected world power, with a strong Navy leading the way.”

The Great White Fleet cruise had dual origins—a diplomatic crisis with Japan and a need to test new U.S. battleships. On June 27, 1907, at the height of tensions in Japanese-American relations, Roosevelt decided to send the Atlantic battleship fleet to the Pacific in the fall. With nearly all U.S. battleships in the Atlantic Fleet, the U.S. naval force in the Pacific was no match for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Aware of this situation, residents on the U.S. West Coast felt vulnerable to an attack. Coinciding with tensions with Japan, the Atlantic Fleet possessed a sufficient number of new first-class battleships available for sustained operations. Roosevelt seized the opportunity and ordered these ships to the Pacific. The exercise would test the new battleships’ mechanical systems and their ability to reach the Pacific in good condition to engage an enemy, as well as bolster the security of the West Coast. On July 2, Secretary of the Navy Victor Metcalf announced that the fleet would steam around Cape Horn on a practice cruise and would later make its way to the San Francisco Bay. He mentioned nothing about the fleet’s route back to the Atlantic, because he wanted to remain flexible in case a circumnavigation of the globe proved impractical. The administration would wait with an announcement of intent until the fleet reached the west coast of Mexico. If it had no major mechanical difficulties, the U.S. government would officially state that the fleet would return to the Atlantic by way of Australia, the Philippines, the Suez Canal, and the Mediterranean.

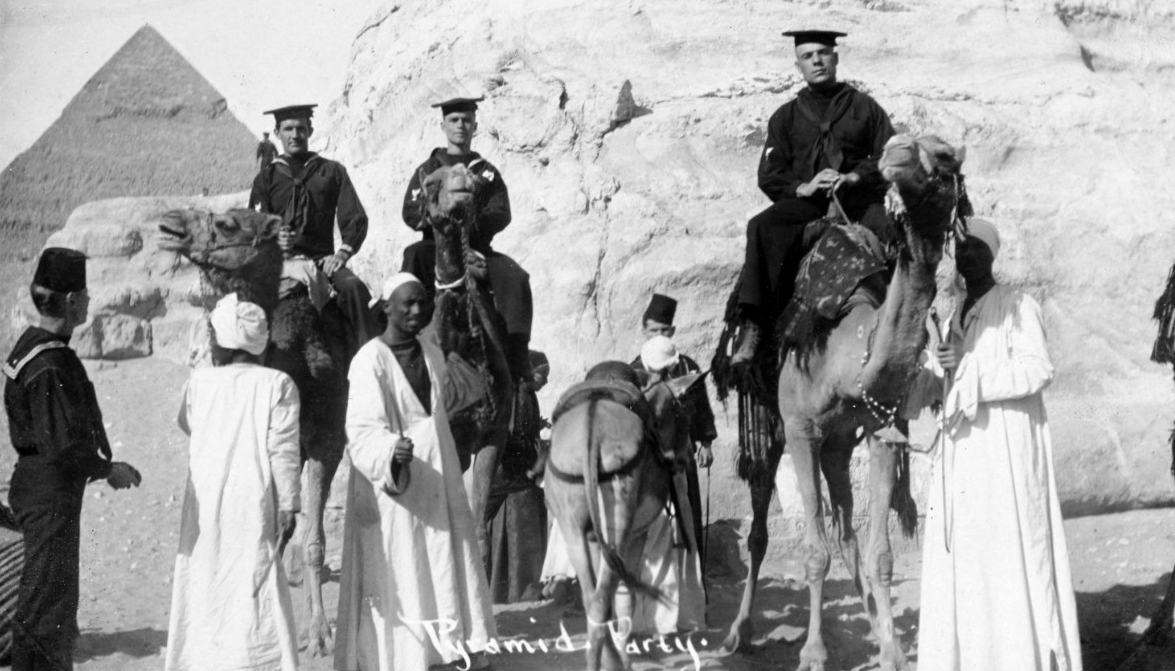

When the first leg of the trip began, the battleships departed Hampton Roads for their first stop, at Port of Spain, Trinidad, where they anchored on Dec. 23 to coal. The fleet crossed the line on Jan. 6 and anchored in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, six days later. From there, it proceeded south to Punta Arenas, Chile, where the ships stopped once again to coal. After passing through the Strait of Magellan without any problems, the fleet paraded through the harbor of Valparaiso, Chile, without stopping, then continued north. On Feb. 20, it arrived at Callao, Peru. During every port call, officers attended formal receptions and Sailors enjoyed liberty ashore. After pausing a month in Magdalena Bay off Mexico’s Baja California, the fleet reentered U.S. territory and dropped anchor at Coronado, California, on April 14. Four days later, the fleet steamed north to Los Angeles. On the way to San Francisco, the fleet visited Santa Barbara, Monterey, and Santa Cruz. Over the course of nearly three months, elements of the fleet visited cities up and down the West Coast. The entire fleet visited Seattle. Some of its ships went into dry dock at Bellingham, Washington, to have their hulls cleaned, while others returned to San Francisco.

On July 7, 1908, the entire fleet departed San Francisco for the second leg of the cruise across the Pacific. On July 16, the fleet arrived at Honolulu, Hawaii, where the officers enjoyed luaus and sailing regattas. The ships departed six days later, reaching Auckland, New Zealand, on Aug. 9. After six days of festivities there, the fleet proceeded to Australia, spending nearly a month visiting the ports of Sydney, Melbourne, and Albany. On their way to Japan, the fleet made a stop at Manila, Philippine Islands, where a cholera epidemic prevented Sailors from taking liberty in the city. Yokohama, Japan, extended its hospitality to the fleet for a week, beginning Oct. 18. Following a visit to Amoy (present-day Xiamen), China, the fleet practiced gunnery in Manila Bay.

On Dec. 1, the Great White Fleet departed Manila for the third and final leg of the cruise. It made way through the South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, and the Indian Ocean to Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where it remained for a week. After traversing the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden, and the Red Sea, the fleet arrived at Suez, Egypt, on Jan. 3, 1909. It then passed through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean Sea. In January, the fleet split up to make several port calls, including Algiers, Tripoli, Naples, Marseille, Athens, and Malta, while several ships were detached to aid victims of an earthquake and a tidal wave on Sicily. By Feb. 6, the fleet had rejoined at Gibraltar. On Feb. 22, the Great White Fleet arrived back home in Hampton Roads, completing a circumnavigation of the globe just two weeks before Roosevelt left office.

The world cruise of the Great White Fleet was a diplomatic victory. Besides demonstrating that the United States could project power globally, it improved relations with many countries, notably Australia and Japan. The cruise also fulfilled Roosevelt’s expectation that the Great White Fleet would help educate the American public about naval operations and stimulate widespread support for the U.S. Navy. Moreover, it provided Navy personnel with practical experience in sea duty and ship handling, leading to improved formation steaming, fuel economy, and morale.

Shortly after their arrival back home, the ships underwent major changes to their appearance. New cage masts with fire-control tops replaced old-style masts with fighting tops, and the ships were repainted battleship gray. All too soon, though, they would become obsolete with the launching of the Royal Navy’s HMS Dreadnought, which revolutionized naval power with its steam turbines and all-big-gun armament. Nonetheless, the world cruise of the Great White Fleet invigorated a national commitment to naval power and inspired the United States to have a Navy second to none.

Navy SEALs Established 60 Years Ago

Beginning in January 1962, in response to President John F. Kennedy’s desire for the services to develop unconventional warfare capabilities, the U.S. Navy established SEAL (Sea, Air, Land) Teams 1 and 2 with the mission of conducting counter-guerilla warfare and clandestine operations in riverine and maritime environments. During the Vietnam War, SEAL involvement began immediately and was initially advisory in nature. SEALs instructed South Vietnamese troops in tactics, conducting a training course for the Biet Hai commandos. In February 1966, a SEAL Team 1 detachment arrived in Vietnam to conduct direct-action missions. Eventually, eight SEAL platoons would have a presence in the country on a continuous basis for much of the conflict. Post-Vietnam operations included Urgent Fury (Grenada 1983); Earnest Will (Persian Gulf 1987–90); Just Cause (Panama 1989–90); and Desert Shield/Desert Storm (1990–91). Additionally, SEALs conducted operations in Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, and Liberia.

In response to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, SEALs had boots on the ground in Afghanistan by October. The first military flag officer to set foot in Afghanistan was a Navy SEAL, who was in charge of special operations for U.S. Central Command. During Operation Enduring Freedom, SEALs carried out hundreds of special reconnaissance and direct action missions. SEALs also operated in the Philippines and on the Horn of Africa as part of the global war on terrorism. On May 2, 2011, SEAL Team 6 raided an al-Qaeda compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, killing the mastermind behind the Sept. 11 attacks—Osama bin Laden. Operation Iraqi Freedom was the largest SEAL deployment in its history. SEALs were instrumental in numerous special reconnaissance and direct action missions to include the security of oil infrastructures and offshore gas and oil terminals; waterway clearance operations that enabled humanitarian aid; capture-or-kill high-value targeting; and raids on suspected chemical, biological, and radiological warfare sites.

U.S. naval special warfare traces its roots to the scouts and raiders, naval combat demolition units, combat swimmers, underwater demolition teams (UDTs), and motor torpedo boat squadrons of World War II. On Aug. 15, 1942, to meet the need for a beach reconnaissance force, selected Navy and Army personnel began joint training at Amphibious Training Base Little Creek, Virginia. Scouts and raiders were trained to identify and reconnoiter the objective beach, maintain a position on a designated beach prior to a landing, and guide the assault to the landing beach. The first group of trained operators included Capt. Phil H. Bucklew—known as the “Father of Naval Special Warfare”—who saw action during the invasions of North Africa, Salerno, Sicily, Anzio, Normandy, and southern France. A second group of scouts and raiders, code-named Special Service Unit 1, was established on July 7, 1943, as a joint and combined operations force whose first mission was on New Guinea. Later operations included Gasmata, Arawe, Cape Gloucester, and New Britain. Inter-service conflicts soon arose over operational matters, and all non-Navy personnel were subsequently reassigned. The unit was renamed the 7th Amphibious Scouts, and it conducted operations in the Pacific for the duration of the war, participating in more than 40 landings. A third team was formed, and operated mostly in China. To bolster the Navy’s operational ranks, Adm. Ernest J. King ordered 120 officers and 900 men be trained for “Amphibious Roger” at Fort Pierce, Florida. Combat demolition units were formed as well. Lt. Cmdr. Draper L. Kauffman—known as a founding father of naval combat demolition tactics—established a school to train personnel to eliminate obstacles on an enemy-held beach prior to an invasion. Combat demolition units operated extensively throughout the European and Pacific theaters. At the conclusion of the war, rapid demobilization reduced the number of active duty UDTs to just two on each American coast.

During the Korean War, one of the remaining UDTs expanded to three teams with a combined strength of 300 operators. As part of a Special Operations Group, UDTs conducted demolition raids on railroad tunnels and bridges along the Korean coast. The “frogmen,” as they became to be known, also participated in the amphibious landing at Inchon, mine-clearing operations in Wonsan Harbor, and Operation Fishnet. For more on naval special warfare, visit NHHC’s website.

Confederate Batteries Attacked on Christmas Day

On Dec. 25, 1863, Confederate batteries on Johns Island attacked the gunboat Marblehead near Legareville, South Carolina, in the Stono River. The Confederates were trying to neutralize the fire support that Marblehead was providing for U.S. Army troops on the shore. After about an hour, the Confederates broke off the engagement and withdrew. Although the ship was moderately damaged, Marblehead’s crew was still able to capture two of the enemy's 8‑inch seacoast howitzers before heading north for repairs and reassignment. Marblehead would never return to action during the Civil War and served out the rest of its career as a practice ship for the U.S. Naval Academy.

The Christmas Day Battle of Legareville was the Confederates’ attempt to surprise Union forces, who had a small force of about 200 infantrymen just outside the South Carolina city. Marblehead was the lone Union ship providing direct support to land forces. Sloop Pawnee and mortar schooner C. P. Williams were posted farther down the inlet. At around 6 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on the ship. Lt. Cmdr. Richard W. Meade, commander of Marblehead and still wearing his nightclothes, ran to the deck and ordered his crew to return fire. Another Confederate battery was also firing on the Union infantrymen. Confederate Col. Powhatan Page had a distinct advantage over the Union troops in numbers of men, but he refused to advance until Marblehead had been destroyed. By 7:30 a.m., the Confederates withdrew due to their inability to keep Marblehead out of the fight. Both the Union forces and Confederates had three killed. Page blamed poor artillery for the inconclusive battle, although Marblehead was hit 20 times.

For his actions on that day, Boatswain’s Mate William Farley received the Medal of Honor for inspiring his men to keep up rapid, effective fire during the engagement. Quartermaster James Miller also received the nation’s highest honor for his courage under fierce hostile fire, and Contraband Robert Blake, who was an escaped slave, was the third of the Marblehead crew to receive the medal. Blake, “while serving the rifle gun carried out his duties bravely throughout the engagement, which resulted in the enemy's abandonment of their positions, leaving a caisson and one gun behind.”