The Phinney Site: An Archaeological Investigation of a Revolutionary War Site

During the mid-1990's, Brent Phinney, owner of a sawmill and steel fabrication shop in Brewer, Maine, discovered the remains of a wooden shipwreck in shallow water just off the eastern shoreline of the Penobscot River. In June 1998, Phinney contacted Warren Riess, Research Associate Professor of History and Marine Sciences, University of Maine (Darling Marine Center), who in turn contacted representatives of the Naval Historical Center (NHC) Underwater Archaeology (UA) Branch. UA initiated the first phase of the Penobscot Expedition Archaeological Project by conducting a reconnaissance site investigation of the Phinney Site in fall 1999 and 2000. Analysis of the shipwreck and its associated artifact assemblage led NHC archaeologists to conclude that the Phinney Site represented the remains of a small eighteenth-century vessel that comprised one of the ill-fated American fleet that participated in the Penobscot Expedition of 1779.

The Penobscot Expedition

In June 1779, the British sent a contingent of soldiers to Majabagaduce, Massachusetts (present-day Castine, Maine) and established the military and political headquarters of a new colony for loyalist subjects fleeing the rebellious colonies. In addition, the new fortification (Fort George) served as a source of protection for British shipping operating in the Bay of Fundy and along the coast of Nova Scotia, and prevented a land assault against southern Canada by American forces. On 24 July 1779 a combined American naval and land force of approximately 40 ships and almost 3,000 men under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall entered Penobscot Bay and laid siege to the new fort. Just as victory appeared to be within their grasp, the Americans were forced into a disorganized retreat up the Penobscot River by a British relief squadron that arrived at the entrance to the bay during the first half of August.

The British squadron was commanded by Sir George Collier and comprised of six vessels: the 64-gun line-of-battle ship Raisonable, 32-gun frigates Blonde and Virginia, 28-gun frigate Greyhound, and 20-gun frigates Galatea and Camilla. As the opposing fleet closed in on the mouth of the bay, an American lookout vessel rushed to the flagship Warren to alert the Commodore. Saltonstall, greatly unnerved by the news, hastily convened a council of war. At its conclusion, all members voted unanimously to evacuate the land forces and retreat up the Penobscot River. During the early morning hours of 14 August, the Continental Army deserted their lines and re-embarked their troops and equipment aboard transports.

The transports attempted to run up the river, but were hampered by a lack of wind. The same problem prevented the American fleet's armed vessels and privateers from effectively forming a defensive crescent around the retreating transports. A sea breeze finally materialized during the early afternoon, allowing the British squadron to enter the harbor under full sail. As the first of the British frigates drew within firing range of the American fleet, Commodore Saltonstall signaled to all of his subordinates that it was every man for himself. Panic rapidly consumed the Americans-three vessels (the New Hampshire State brig Hampden and privateers Hunter and Defence) attempted to escape along the west side of Long Island, but were cut off by Blonde, Camilla, and Galatea and either captured or scuttled. Several of the transports now had the wind in their favor but were unable to sail against the ebbing tide. As the British ships fired the first of several cannon salvos, the crews of most of the fleeing transports ran their vessels ashore, set them ablaze, and scattered into the countryside. A total of nine transports were captured. The rest of the American fleet-all of the naval vessels and some of the privateers and transports-escaped into the Penobscot River.

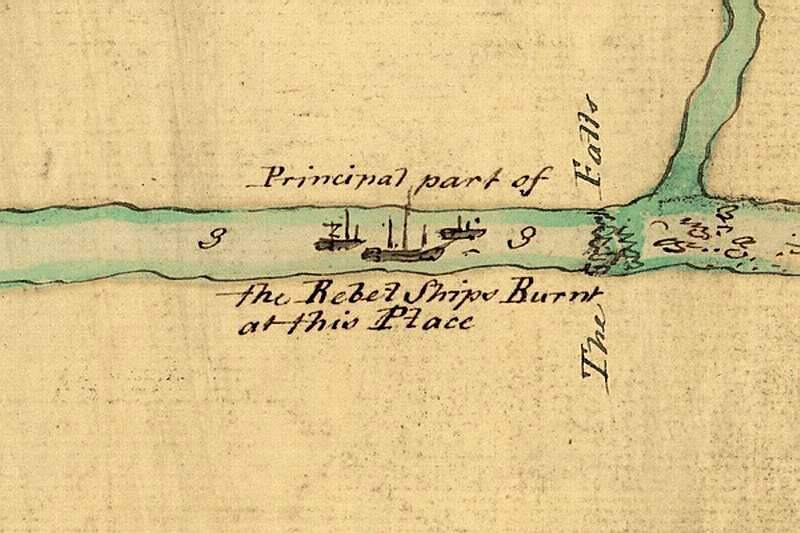

The surviving American vessels managed to progress upriver, albeit slowly and with considerable effort from their crews. Unfortunately, some ships began to lag behind the others. Many, including the ordnance transport Samuel, were abandoned and torched near the present-day town of Winterport. Other vessels, including the Continental Navy vessels Warren, Providence, and Diligent; the Massachusetts State Navy ships Tyrannicide, Active, and Hazzard; a small number of privateers, and one surviving transport (the sloop Pidgeon), continued to slowly move north toward the river's head. The Warren's progress was severely hindered by its massive size, and it was soon unable to keep up with the rest of the fleet. Consequently, Saltonstall ordered his crew to heave to and anchor the flagship near Oak Point. The rest of the fleet pressed on, finally coming to anchor around midnight 14 August. The following morning, they resumed the journey, sailing as far as the falls at Bangor. Unable to proceed further upriver, the commanders of the remaining vessels in the expedition made preparations for a final stand against the British. Of the approximately 40 American ships that sailed into Penobscot Bay on 25 July, only ten survived the retreat to Bangor. The once powerful armada was now comprised of two small Continental Navy vessels, three Massachusetts State Navy brigs, four privateers, and one unarmed transport.

On the night of 15 August, American General Solomon Lovell appeared aboard Providence and informed the naval officers that Saltonstall needed assistance to tow theWarren upriver. News that the flagship had not yet been destroyed invigorated the men, and numerous boats were promptly manned and sent down to Oak Point. Despite such good tidings, the privateer crews began scuttling their vessels during the early morning hours of August 16. The first vessel to be destroyed was the transport Pigeon, followed shortly thereafter by Hector and Black Prince. Monmouth exploded as flames from Black Prince reached its deck guns and powder stores. A few hours later, a messenger arrived from Oak Point with news that the Warren had been set ablaze on Saltonstall's orders and was already consumed. The same fate befell the privateers downriver. With no other option left to them, the officers and crew of the remaining ships abandoned their craft and set them on fire. Since most were "half a pistol shot" or less apart, the flames rapidly spread from one vessel to another. By late afternoon 16 August, the river near Bangor was filled with the smoldering hulks of ships that had either exploded or burned to the waterline and slipped beneath the water. Only forty-eight hours after Collier's British squadron arrived at the mouth of Penobscot Bay, most of the American fleet lay in ruins along the course of the river.

Archaeological Investigations at the Phinney Site

Presently, the remains of approximately 30 watercraft associated with the Penobscot Expedition are believed to be in the Penobscot Bay and River system, all of which are potentially significant cultural and historical resources. Because the majority of these sites are near populated areas, they risk the detrimental impacts of natural forces (erosion, decomposition, etc.), land and water development, and the depredations of opportunistic relic hunters. Consequently, submerged archaeological resources associated with the Penobscot Expedition are the focus of a number of research projects, including one developed by the Naval Historical Center.

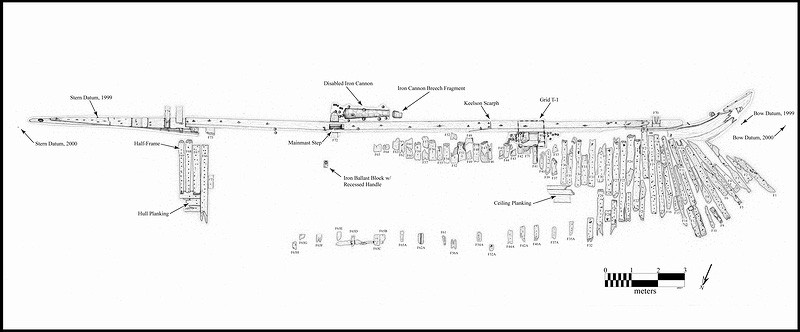

Over the course of two field seasons (1999 and 2000), NHC archaeologists conducted a brief examination and assessment of the Phinney Site's exposed components, and initiated limited test excavation, artifact recovery, and documentation of the ship's architecture. A myriad of artifacts were recovered from the hull remains. The artifact assemblage included numerous ceramic and glass fragments, a wide variety of iron and lead shot, a copper-alloy shoe buckle, wooden sheaves (pulleys for block and tackle), a fragment of copper sheathing, and a partially burned wooden rigging block. The presence of the burned block and numerous fragments of charcoal and charred wood within the wreck remains indicate that the ship burned before it sank. Two broken iron cannon were discovered laying parallel to the wreck's centerline, but were not recovered. In situ examination of both specimens revealed that they are colonial-era 4-pounders with an estimated weight of 11 or 12 hundredweight each. The positions of both guns within the hull, combined with their inoperable state, strongly suggest that they were stowed in the ship as ballast.

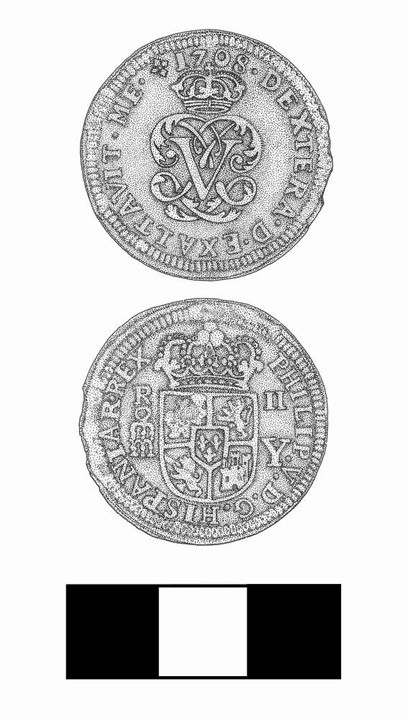

During the 2000 field season, a small silver coin was located at the base of the vessel's mainmast step mortise. Conservation and analysis of the coin revealed that it is a Spanish 2-reales produced at the Royal Mint Mill in Segovia, Spain in 1708 (during the reign of Philip V). The specimen was the result of a method of production called roller-mill (or roller-struck) coining. The 2-Reale coin, also known in the English colonies as a pistareen, enjoyed wide circulation in the English colonies of North America prior to, during, and after the American Revolution. In fact, it is estimated that half of the coins in colonial America were various denominations of Spanish reales. While most of the coins used in the English colonies were minted in the New World, some Spanish coins minted in Spain circulated as well. The coins minted in Spain were referred to as "new plate" since they were 20-percent lighter than Spanish colonial coins. The pistareen was one of these coins. Since most coinage in the American colonies remained in circulation years after being issued, the presence of a low-denomination 1708 coin aboard a suspected Revolutionary War-era vessel is not at all surprising.

The vessel's surviving hull structure is remarkably well preserved, and consists of a variety of components including the keel, keelson, apron, stem, sternpost, floors, and cant frames. The ship's architecture compares favorably to previously-investigated eighteenth-century shipwrecks, including the privateer Defence (scuttled during the Penobscot Expedition), British collier Betsey (scuttled at Yorktown, Virginia in the closing days of the American Revolution), the Devereaux Cove Wreck (believed to be a scuttled transport from the Penobscot Expedition), the Terrence Bay Wreck (a mid-eighteenth century fishing schooner wrecked near Halifax, Nova Scotia), and the Reader's Point sloop (a middle-to-late eighteenth century vessel abandoned in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica). The Phinney Site likely was rigged as either a brig or schooner, based on its preserved keel length (approximately 80 feet), the relative positions of the main and foremast steps, its scantlings, projected tonnage (244.2 tons) and other attributes. All of the aforementioned compare favorably with characteristics of mid-eighteenth century brigs and schooners observed in both the archaeological and historical records. Wood samples recovered from a variety of hull components indicate that the ship was manufactured predominantly from white and red oak, while sediment samples obtained from the bilge revealed the presence of pollen from a variety of plants native to the northeastern United States. When taken together, both the wood and pollen samples point to a vessel that was likely constructed and outfitted in an American shipyard, and that operated primarily in North American waters.

There is now little doubt of the Phinney Site's association with the Penobscot Expedition; however, the exact identity of the vessel that the wreck represents remains an open question. Detailed analysis of the hull and artifact assemblage has enabled UA staff to establish a temporal framework (American Revolution-era) and nationality (American) for the wreck. Further, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the vessel was heavily armed, either as a Continental or State Navy warship or commissioned privateer. Despite these clues, no "smoking gun" that positively identifies the Phinney Site has yet been uncovered. Consequently, historical research has been initiated at a number of archives in an attempt to find pertinent documents such as ship plans, logbooks, and maps. As they are located, these items will be examined to assess the attributes of American vessels that served in the Penobscot Expedition and determine the final disposition of those scuttled during the final days of the engagement. NHC archaeologists continue to conduct periodic site visits to determine the wreck's state of preservation, and may initiate additional archaeological investigations as time and funding permit.