“The Most Terrifying Experience”: The U.S. Navy and the Pandemic of 1918

As the novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, continues to shape day-to-day life across the globe, we are repeatedly reminded that what we are experiencing is nothing less than a once-in-a-century pandemic. The title is remarkably apt, for COVID-19 is striking 102 years—almost exactly a century—since one of the greatest public health crises in history. From the spring of 1918 through the first months of 1919, a never-before-encountered strain of influenza wreaked havoc worldwide, killing more people than World War I and leaving a legacy of terror so great survivors were loath to even speak of it.[1] The 1918 influenza pandemic left at least 50 million people dead worldwide.[2] In the United States, it killed an estimated 675,000, claiming over 10 times as many American lives as the war with which it coincided.

The 1918 influenza pandemic was a wartime plague, and it is impossible to understand apart from its context in the midst of the Great War. Indeed, even its (incorrect) name, the Spanish flu, was a product of the war; since Spain was neutral, the Spanish government was among the few that did not censor the alarming reports of the disease ravaging its population, leading to a false impression that it had struck Spain particularly hard.[3] The war made the severity of the pandemic possible, crowding people together in severely congested camps and trenches, moving the infected from one population center to another in mass numbers, placing thousands of people who had never travelled more than a few miles from home in unfamiliar disease environments, and hampering even the most basic of procedures for containing its spread.

At the forefront of the United States’ participation in the war effort, the Navy stands out among American institutions for the severity of its suffering during the pandemic. Indeed, one historian refers to the early weeks of the outbreak as “largely a naval affair.”[4] Naval personnel, crowded on ships and in navy yards, were prime targets for the disease. Those in the theater of combat in Europe were likewise among its victims, and the strains of warfare overshadowed all efforts to combat the virus. Yet the Navy was also at the forefront of the fight against influenza. Navy nurses and doctors put their own lives at risk to treat personnel and civilians alike. Naval officers took the lead in cities across America to bring the pandemic under control. And the Navy’s scientific minds played a key role in researching the virus and seeking a cure. They were not always successful, but their efforts made the pandemic less disastrous than it otherwise would have been, and their endurance through often nightmarish circumstances was every bit as creditable to the ideals of the service as those waging war against Germany. This is their story.

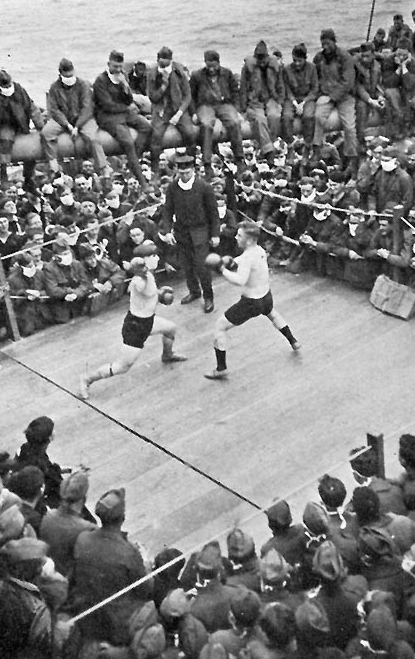

USS Siboney. Boxing match on the ship's forecastle, while she was at sea in the Atlantic Ocean, transporting troops to or from France in 1918–1919. Spectators are wearing masks as a precaution against the spread of influenza. (NH 103264)

In late June of 1918, Vice Admiral William S. Sims, commander of American naval forces in Europe, casually mentioned to his wife that “there is a sort of mild influenza going the rounds” among American forces in Europe, but he was not particularly concerned. The illness, he said, “lasts but a few days,” and he trusted his own solid health to protect him from infection.[5] Other commanders showed less indifference, but it seems no one among the American naval officers in the war zone saw the outbreaks in their ranks as a major threat. Admiral Henry B. Wilson, commanding U.S. naval forces in France, acknowledged a “mild epidemic” among his men a week later but reassured Sims that “there is no reason for alarm.”[6] More ominous news trickled in from American forces serving with the British Grand Fleet in the North Sea, where their commander reported quarantining one of his ships in late May, and by the end of June had “a number of serious cases” resulting in multiple deaths.[7] From the Mediterranean, Rear Admiral Albert P. Niblack reported in passing that two of his ships had been unable to sail on schedule due to major outbreaks, but neither officer expressed any concern that the influenza would hamper their forces’ effectiveness.[8] Similarly, a troop transport noted an outbreak in May that afflicted over 20 percent of the men aboard, but the commanding officer cheerfully reported that all made “uneventful recoveries,” and he found that simply providing ample fresh air was sufficient to restore the afflicted men’s health.[9] Disease was a fact of life aboard crowded ships, and a recent measles outbreak was a source of greater concern than what seemed a mild and only briefly incapacitating strain of the common flu.[10] And for America’s naval leadership, like that of their allies, the ongoing tenacity of the German army dominated their attention. A massive German offensive raged along the Western Front, and French and British generals frantically warned their new allies that the outcome of the war hung in the balance.[11] With the Allied nations struggling to hold the war effort together long enough for American manpower to make a material difference, an attack of seasonal flu barely registered on anyone’s mind.

Still, back in the United States, there were ominous signs. Early in 1918, over 1,000 men at a Ford plant in Detroit contracted the flu, while as far away as California, the famed San Quentin Prison saw over a quarter of its population sickened. About the same time, a uniquely severe strain of influenza struck in remote Haskell County, Kansas. It had run its course by early spring—seemingly, at least—but the grippe, as it was known, travelled with young men from Haskell into Camp Funston, a military cantonment 200 miles away. Over 1,100 men at Funston came down with a flu severe enough to require hospitalization in March 1918. That was only a fraction of the actual number, however, as thousands of other sick men were crammed into whatever medical facilities were available in the area.[12] From there, men were transported to various other facilities around the country, and across the Atlantic to the war in Europe.

The timing of the outbreak in Kansas and its subsequent spread to Camp Funston and then Europe has led many scholars to conclude that Haskell County was the birthplace of the pandemic.[13] Other indicators point to an Asian or European origin, however, and 1916 and 1917 also saw outbreaks of influenza that could conceivably have been forerunners of the great plague of 1918.[14] In his comprehensive study of the pandemic, commissioned by the American Medical Association in the 1920s, bacteriologist Dr. Edwin O. Jordan explored a host of localized outbreaks in late 1916 and early 1917, including Haskell County, that had been posited as the earliest occurrence of the virus. His results, however, were so inconclusive that he was forced to conclude that the “primary origin of the 1918 pandemic cannot be traced with any degree of plausibility to any one of these localized outbreaks.”[15] Historian John M. Barry, a more recent scholar of the 1918 influenza, is far more confident. The key for Barry is the ability to track the pandemic’s spread: “One can trace with perfect definiteness the route of the virus from Haskell to the outside world,” he argues, a crucial factor that every other theory of origin lacks.[16]

Wherever its origin, the spring 1918 influenza epidemic wreaked havoc on a few military installations and left behind an unusually high number of deaths in several cities, though not high enough to attract attention until after the fact. All told it came and went with little impact on the U.S. Navy or the wider war.[17] German General Erich F. W. Ludendorff (conveniently) later cited influenza outbreaks as one of the main reasons his offensive on the Western Front failed. Likewise, the influenza created minor difficulties for Allied armies on the Western Front as many soldiers became incapable of duty during periods of intense combat.[18] Nevertheless, events seemed to back up the casual optimism showed by Sims and his chief of staff, Nathan C. Twining, who had confidently reported in May that the flu did not produce any “serious cases” and that “a prolonged continuance of the epidemic is not anticipated.”[19]

Perhaps Twining was not entirely wrong. The massive difference in deaths between the spring and fall outbreaks has led some to speculate they were different strains of influenza.[20] More likely, the virus did not disappear over the summer; it merely underwent a mutation. Scientists describe this process as “passage”—the adaptation of a pathogen as it transfers itself from one host to another. Sometimes the changing environment drains the pathogen of its ability to kill. The Ebola virus, for example, loses lethality fairly quickly after an outbreak. Other pathogens take the opposite path, however, becoming deadlier as they adapt. The seemingly mild influenza in the spring of 1918 fell in this category and grew increasingly lethal in the summer months. Meanwhile, those observers who had taken special note of it in the spring assumed it had disappeared. “As it smoldered at the roots,” Barry recounts, the process of passage “was sharpening its ferocity.” Far from fizzling out, it was “becoming increasingly efficient at reproducing itself in humans. Passage was forging a killing inferno.”[21]

• • •

For the Navy, the first glimpse of the coming disaster appeared near the top of the chain of command. During a summer tour of Europe shortly after the end of the spring wave in the United States, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt came down with something very much like influenza. After touring the battlefields in France in July, Roosevelt collapsed as he boarded Leviathan (SP-1326) for his return to the United States. Pneumonia set in quickly, and the assistant secretary spent the return voyage confined to a bed and coughing uncontrollably. Upon arrival in New York, he went straight from the ship onto a stretcher and spent the next month confined to his home at Hyde Park. The bout with influenza had dramatic implications for Roosevelt’s life; it scuttled his plans to resign from the Navy Department and enlist for service on the Front. Delirious and bedridden upon coming home, he also missed the chance to conceal letters from his lover, Lucy Mercer, which his wife Eleanor discovered while unpacking his luggage, creating a major crisis in the Roosevelt household. Fortunately for the nation, both Roosevelt and his marriage survived.[22] Others would not be so fortunate.

Despite its length and severity, Roosevelt’s illness raised no warning flags of influenza. His isolated case was recognized as a harbinger of things to come only in retrospect. The first unmistakable signs of the impending inferno in the United States appeared at a naval station in Boston around the same time as Roosevelt was emerging from his convalescence. The Commonwealth Pier served as a way station for men passing through Boston on their way to Europe, and the wartime boom in personnel had left it badly overcrowded. The Surgeon General of the Navy warned the Navy Department that some spaces were crammed with twice as many men as they were built to handle, conditions that “lend themselves to the spread of the disease.”[23] And spread it did. The Commonweath Pier reported three cases on 27 August. On 29 August, it was up to 58. On 3 September, exactly a week after the first disease appeared, 119 new cases were reported. An epidemic had begun. By the end of the second week, the First Naval District, headquartered in Boston, reported over 2,000 personnel stricken with the flu. By then, the outbreak had already spread to the civilian population in Boston and the surrounding area.[24]

This was the beginning in the United States of the second wave of the pandemic. The new wave struck with a severity that brought to mind the horrors of the medieval Black Death. In fact, it went on to claim more lives in one year than the Black Death had taken in over a century. In cities across America, essential services collapsed as phone companies, police and fire departments, social workers, medical personnel, and undertakers all saw their workforces gutted by outbreaks. Bodies were left to rot in homes and in the streets. Social services were overwhelmed by an influx of orphans and no one to take them in. Doctors reported going home late at night to get a few hours’ sleep, only to find the next morning that the section of the hospital devoted to acute cases had been emptied in the night; death had claimed them all, and there were plenty of new patients to take their place. Others recalled driving to and from hospitals on completely deserted roads, no matter the time of day.[25]

Survivors later recalled one of the most prominent factors of the pandemic was the fear that it generated during the fall of 1918. In the hardest-hit cities, people were terrified to go near one another to the point that family members refused to look in on sick, potentially dead relatives, and survivors were trapped in their homes with corpses because no one would come to take the dead away. In all, nearly half the deaths in the United States that fall were the result of this new strain of influenza, and so many perished that the average life expectancy for Americans dropped a full decade.[26] At one particularly bleak moment of the second wave, despair seemed to overtake Dr. Victor C. Vaughan, dean of the University of Michigan Medical School, who was temporarily serving with the Army Medical Department. In a grim report, he added a handwritten note: “If the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear…from the face of the earth within a matter of weeks.”[27]

Part of the reason average life spans took such a hit was that the virus made no distinction between young and old. The norm for influenza epidemics is that those at the beginning and end of their life spans die, but the otherwise healthy person in their twenties or thirties who succumbs is a rare outlier. The 1918 influenza pandemic perversely seemed more likely to claim the young and healthy. The most vulnerable group of all was pregnant women, but people in their twenties through their forties—of either sex and of any prior health condition—made up the highest number of deaths. Besides the tragedy of this—the fact that these victims were, as one doctor put it, “doubly dead in that they died so young”—the death toll among people in the prime of life meant that those tasked with caring for the sick and keeping society functioning were the most likely to be incapacitated.[28]

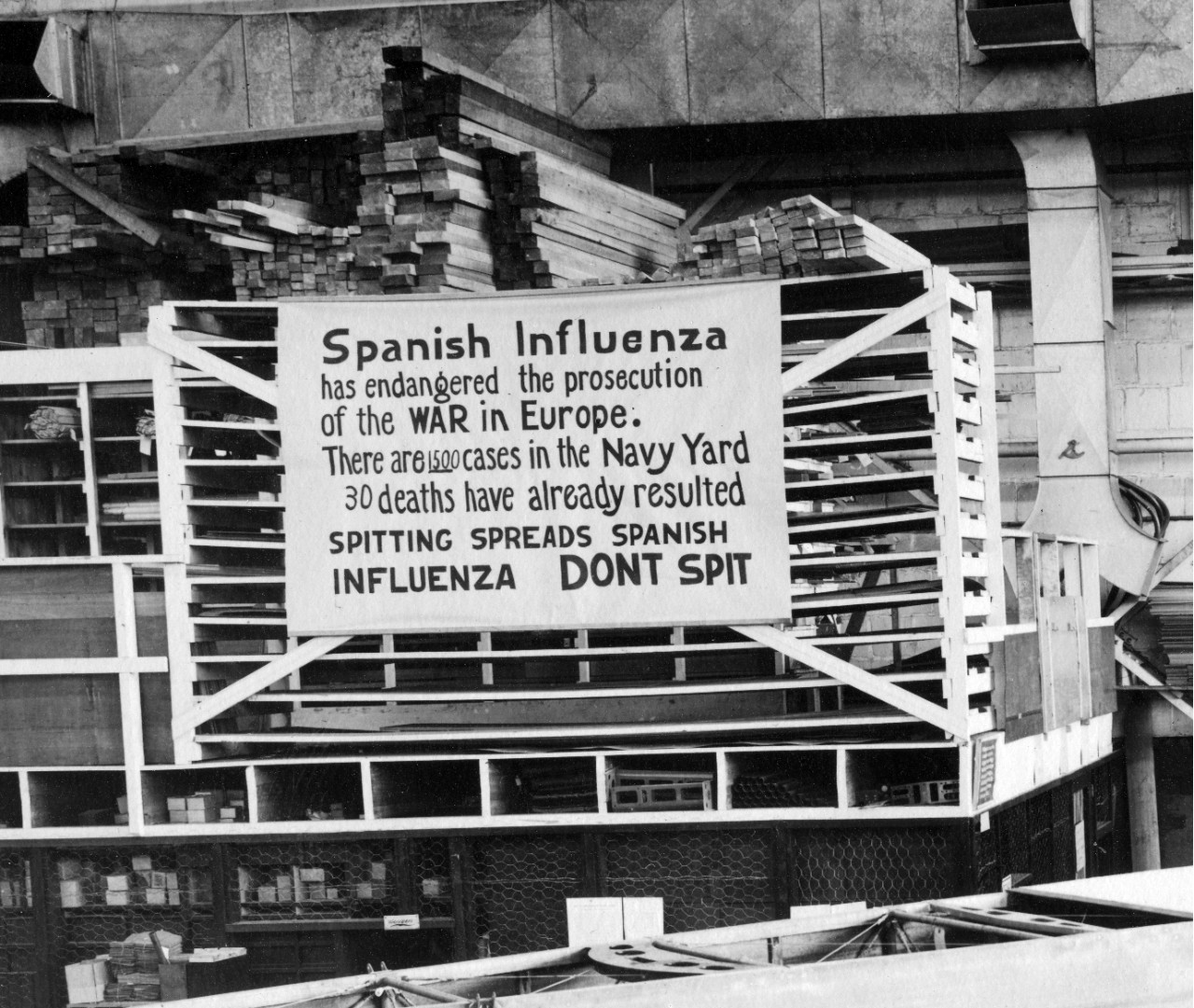

Influenza precaution sign mounted on a wood storage crib at the Naval Aircraft Factory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 19 October 1918. As the sign indicates, the 1918 Influenza was then extremely active in Philadelphia, with many victims in the Philadelphia Navy Yard and the Naval Aircraft Factory. Note the sign’s emphasis on the epidemic's damage to the war effort. This image is cropped from Photo #NH 41731. (NH 41731-A)

The naval installation that suffered the most was the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Over 300 Sailors from Boston arrived there on 7 September at the height of the epidemic in Massachusetts. Within a week, the number of new cases needing hospitalization had filled the base’s medical facilities to overflowing, and Sailors were being sent to local hospitals. Even that was not sufficient, and the Red Cross chapter in the city had to convert a nearby building into an additional emergency hospital, with all of its 500 beds reserved for navy yard patients. Alarmingly, five percent of the naval personnel died, a staggering death toll that would be matched (and exceeded) in cities across the world.[29]

From the navy yard, the virus spread through Philadelphia with a previously unimaginable fury. The local hospital was already overwhelmed on 17 September when five doctors and 14 nurses became patients themselves in the course of a single day. During one week in October, over 4,000 Philadelphians died. One morgue was soon stuffed with over 200 bodies—it was built to hold 36. And this morgue’s situation would have been much worse if the city had been able to keep up with the constant rate of deaths. As it was, bodies lay in homes for days at a time and streets were lined with corpses awaiting someone, anyone, to take them away. A corrupt and often incompetent local government combined with horrific overcrowding in the city’s poor tenements made Philadelphia uniquely vulnerable, but the major source of the crisis was the city’s insistence on going forward with a massive Liberty Loan parade on 28 September. Over 200,000 people crammed the city streets to witness the spectacle. The day before the parade, the city’s director of public health, Dr. Wilmer Krusen, reassured the populace that the parade posed no danger. Two days after the parade, he was forced to concede that Philadelphia was in the midst of an epidemic.[30]

Liberty Loan Parade at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 28 September 1918. Naval Aircraft Factory float, featuring the hull of a F5L patrol seaplane, going south on Broad Street, escorted by Sailors with rifles. Note the crowd of onlookers. This parade, with its associated dense gatherings of people, contributed significantly to the massive outbreak of influenza which struck Philadelphia a few days later. (NH 41730)

Philadelphia suffered the most, but it was far from alone. In cities across America, signs of death were everywhere. The hardest-hit cities tended to be those in close proximity to military bases, and naval stations were sites of some of the worst suffering. In Norfolk, Virginia, home of a major naval base, residents complained that people were “dying by the hundred,” so even though the actual fighting was an ocean away, their hometown had begun to feel “like war.”[31] At the naval hospital in Washington, D.C., the death rate in September assumed “startling proportions,” and every effort to treat patients proved fruitless.[32] In New Orleans, the naval station began sending sick men to a local sanitarium when it ran out of room onsite.[33]

Further west, the city of St. Louis, Missouri, managed to avoid the worst of Philadelphia’s fate by cancelling its own Liberty Loan parade and promptly implementing strict procedures to mitigate its spread, including closing schools, banning large gatherings, and temporarily closing a number of businesses.[34] Quick action led to St. Louis suffering a dramatically lower mortality than many other cities. However, by this point the virus could only be mitigated, not stopped, and its spread across the Midwest impacted the Navy as well. At Naval Station Great Lakes on the Illinois shore of Lake Michigan, a massive outbreak nearly overwhelmed the medical facilities. The station had only just finished adjusting for wartime expansion, which caused the population to balloon from 2,500 to over 45,000. The able oversight of Captain William A. Moffett kept the base running smoothly throughout the expansion, but it left the men under his command particularly vulnerable when the pandemic struck.[35] Decades later, Josie M. Brown recounted her arrival as a Navy nurse in the midst of the outbreak. Almost as soon as her bus reached the gate, Brown recalled,

My supervisor took me to a ward that was supposedly caring for 42 patients. There was a man lying on the bed dying and one was lying on the floor. Another man was on a stretcher waiting for the fellow in the bed to die. We would wrap him in a winding sheet because he had stopped breathing. I don’t know whether he was dead or not, but we wrapped him in a winding sheet and left nothing but the big toe on the left foot out with a shipping tag on it to tell the man’s rank, his nearest of kin, and hometown. And the ambulance carried four litters. It would bring us four live ones and take out four dead ones.

For the rest of the fall, Brown and her fellow nurses worked 16-hour days caring for the overload of patients. She had little time to feel sorry for herself, and besides, the nurses were not alone; “morticians worked day and night” as well, she remembered. The base quickly ran out of caskets and was reduced to using makeshift wooden boxes, but even this did not solve the larger problem—the trucks that carried away the dead could not keep up, and the morgue was left with bodies “stacked one on top of the other…packed almost to the ceiling.”[36] One of Brown’s fellow nurses was haunted for years afterward by the sight of those bodies she described as “stacked…floor to ceiling like cord wood.” The haste with which they wrapped and carted off bodies of those assumed to be dead gave her recurring nightmares of “what it would feel like to be that boy that was at the bottom.”[37]

The virus inexorably made its way westward, finally reaching Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California. Fortunately the commandant there, Captain Harry George, had a good idea of what to expect thanks to advance warning from the Great Lakes station. George made sure sufficient beds were on hand and imposed restrictions on liberty and large gatherings. Mare Island thus never faced the crisis that other Navy installations endured, but the neighboring city of Vallejo was not so lucky. The city population had already ballooned due to the need for civilian manpower at the yard, and the overcrowding made an ideal environment for influenza to spread. Soon, the local hospital was overrun, and an emergency hospital was left with one nurse to deal with the influx of patients. Doctors in the city scrambled to treat the hospitalized and keep up with a daunting slate of house calls, and lost amid the crisis was any effort to keep count of the sick, so the full number stricken in the city will never be known.[38]

The virus also spread to South America, where American forces were among its victims. Rear Admiral William B. Caperton recalled putting in at Brazil in early October, where “there came upon us the most terrifying of experiences…the so called Spanish influenza.” A commercial ship from Lisbon, Portugal, put in with an outbreak underway. Four men were already dead by the time the commercial ship crossed the Atlantic, and illness had ravaged the rest of the crew. “The local health authorities, notwithstanding these, made no effort to quarantine the vessel or her passengers,” Caperton reported, with a result that “was not unexpected to us.” On 7 October, Caperton’s flagship, USS Pittsburgh (CA-4), had only a few cases, but the outbreak in the city was creating hundreds of new patients and the shipyard was barely able to keep its work going. A week later, Pittsburgh had over 600 reported cases, and another 350 that were mild enough for the men to keep working despite their condition just so the ship could function. When his men began to die, Caperton discovered that proper burial of bodies in Rio de Janeiro had become nearly impossible. He made arrangements to bury 16 of his men in a local cemetery, only to find that by the time they got there the graves had already been claimed while “eight hundred bodies in all states of decomposition” were lying out in the open, attracting swarms of buzzards. Meanwhile, in the local hospital, “hundreds of naked bodies lay thrown upon each other like cord wood and at least one instance was known of a live man being dragged out from the piles.”[39]

Such suffering and death was, of course, a source of enormous concern, but by far the biggest threat the pandemic posed to the war effort was on board troop transports. By September, the Navy was carrying 250,000 troops across the Atlantic every month. With thousands of men crammed tightly aboard, the transport ships were an ideal environment for the disease to sweep through. Even a subsequent surgeon general’s report conceded that crowding on some ships qualified as “tenement-like conditions.”[40] A group of newspapermen traveling across the Atlantic on a troop transport were horrified as they watched their vessel take on hundreds more men than she had ever been intended to carry, with the result that many troops were “jammed into most uncomfortable quarters,” while others were forced to sleep out on the decks, regardless of inclement weather. Worse, the ship had suffered an outbreak of influenza on its most recent voyage, but the commanding officer rejected the advice of the troops’ commander and pressed on with the voyage after only the most superficial cleaning and with completely inadequate medical facilities aboard. The result was entirely predictable. Over 400 men came down with influenza on the journey to Europe. Twenty-nine of them died crossing the sea, and another 50 were suffering from pneumonia—the primary cause of death from the flu—when they were discharged in Britain.[41]

The newspaper correspondents wrote the president in hopes of preventing another such disaster, and the Cruiser and Transport Force did begin more aggressive efforts to limit outbreaks aboard ships.[42] But the reality was that the war was climaxing at the same time as the pandemic peaked. The Allied armies and the American Expeditionary Forces had succeeded in beating back the final German push of the summer and were now in the process of finally vanquishing the German war machine. The desperate need for men on the Western Front had to take priority; cutting off transports might breathe new life into beleaguered German armies.[43] At one point, President Woodrow Wilson suggested that the Navy should stop all transports until the pandemic could be gotten under control, but he abandoned the idea after strenuous objections from Army Chief of Staff Peyton C. March. March had to accept a reduction, but the survival of the American Expeditionary Forces demanded that shipments of men arrive continuously, regardless of the risk of outbreaks.[44]

No matter the manpower needs, the Navy refused to allow anyone showing symptoms aboard the transport ships. But with a lengthy incubation period, it was hopeless to try and keep asymptomatic patients from bringing the virus with them.[45] In September, George Washington rejected 450 men showing symptoms before setting sail. By its second day at sea, over 500 new cases clogged the medical facilities.[46] Hospital space in ships became so overwhelmed the infected were placed anywhere that could be found. While travelling aboard Briton, Private Robert J. Wallace recalled being diagnosed with influenza after his temperature topped 103º. The doctor told him to grab a blanket and find space on the deck. He lay there for days, enduring bitter cold, biting winds, and rough seas that quickly washed his mess kit overboard. Although delirious with fever, he did vividly remember the orderlies passing through each morning to cart off the dead all around him who had not lasted through the night; it “made for sober conjecture” regarding his own chances. Even after space opened up in what had been a salon during the ship’s pleasure cruising days, medical attention was still hard to come by. Wallace remembered with heartfelt gratitude a memory he will “record in Heaven” of one angelic nurse who washed his feet after learning that he had kept them in soggy boots for 12 days, but he also recalled a patient next to him begging for a drink of water for hours before succumbing, all without anyone able to take notice of him.[47]

Later in September, the 57th Pioneer Infantry boarded Leviathan short several men who had collapsed from influenza on the march to the pier. Even more who showed symptoms were screened out and removed before departure, but it is doubtful anyone held much hope that none of the more than 9,000 men remaining would come down with the disease during passage. The Atlantic crossing became the stuff of nightmares, and those aboard endured things that

cannot be visualized by anyone who has not actually seen them. Pools of blood from severe nasal hemorrhages of many patients were scattered throughout the compartments, and the attendants were powerless to escape tracking through the mess, because of the narrow passages between the bunks. The decks became wet and slippery, groans and cries of the terrified added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment, and altogether a true inferno reigned supreme.[48]

Conditions below decks grew so grotesque that Army details flatly defied direct orders to go down and clean troop compartments, fearing the germs saturating the air far more than any military justice. Sailors from Leviathan’s crew took on this grim task, and in so doing probably kept the death toll from rising high enough to gut the entire ship.[49]

In Europe, the pandemic took a terrible toll on American forces, both on land and sea. Historians estimate that one in four American soldiers contracted the flu at some point during the war, and over 60,000 soldiers died in the pandemic, more than were claimed by enemy fire. The second wave also hampered the American Expeditionary Forces in other ways. Draft calls ceased in October, and training stateside became almost impossible as the disease ravaged camps.[50] Naval facilities in Europe were generally less impacted than those back in the United States, but influenza still took its toll. An American briefly commanded a British submarine after its captain and executive officer both came down with a sudden onset of the flu, which laid up nearly half the men aboard.[51] At Dunkirk, on the French coast, an American naval aviation station saw 90 percent of its personnel contract the virus, while another air station at St. Trojan, France, had multiple days where all functions ceased because too many of the men there were stricken. Likewise, the vitally important destroyer force operating out of Queenstown, Ireland, had to immobilize some of its ships that October because there were not enough healthy Sailors to man them. Still, the Navy refused to let the flu impede the war effort too much. A destroyer at Brest, France, had so many sick that one of the Navy’s medical officers was preparing to pull the entire crew ashore to fumigate the ship, but his plans were interrupted by a report of a vessel being torpedoed nearby. Immediately, every man “slid into place, fever, headache, bone ache and all, and away she beat it to sea and helped pick up the survivors.”[52]

American naval forces in the Mediterranean suffered, sometimes grievously, as well. One commander worried that one or more of the ships in his subchaser detachment would be rendered inoperable because so many of his officers were laid up with the flu, while from Greece another fretted that his subchaser crews were in a constant state of flux because so many kept being taken from their ships to medical facilities.[53] In Gibraltar, a Brazilian squadron delayed joining the American and Allied navies there. Influenza had just ravaged the Brazilian crews, and when the British admiral in command at Gibraltar warned them they would be coming into another serious outbreak, they opted to wait. Niblack lamented to Sims that containing the spread on the station was nearly impossible because of the hopelessness of trying to quarantine when so many thousands of civilian workers passed through daily, and besides, the nearby town was “a pest hole.” Still, Niblack remained more or less cheerfully resigned through the ordeal. The flu “is going to go around the world and nothing can stop it,” he explained to Sims, so best to “let it take its course.”[54]

Niblack’s stoic attitude likely pleased Sims, who also tried to avoid being overly distressed. Even as the pandemic raged around him in London, Sims remained supremely unconcerned (or at least maintained that appearance). During the span of a week in mid-October, 2,225 Londoners died, topping the city’s death toll from all the dreaded zeppelin bombings of the entire war. Yet at the end of the month, Sims reassured his wife that, although the epidemic was “pretty severe,” it was mainly confined to those with poor medical care, and its impact on the city was actually “comparatively little.”[55] It is possible some of his nonchalance was more to maintain morale and prevent his wife from worrying—throughout his time in Europe, he consistently downplayed the risks to his own personal safety in his letters to her. As the situation became increasingly serious, Sims did begin taking more drastic measures, including restricting leave and requesting additional hospital ships. He warned the Navy Department that an unacceptable loss of life could spark a congressional investigation.[56] Still, he was quick to seize on good news. After over 40 cases in the American destroyer flotilla at Queenstown, Ireland, began to show improvement, Sims confidently asserted to the Secretary of the Navy that “the epidemic has practically ceased.” A month later, he came down with influenza himself. Fortunately, he survived and managed to resume his duties after being confined to bed for a week.[57]

Sims’s outlook highlights the fact that, despite the horrific impact the pandemic had worldwide, it stayed in the shadow of what was, at the time, the greatest war humanity had ever seen. In his postwar memoir, Victory at Sea, Sims never even mentioned influenza. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels likewise ignored the pandemic in his extensive postwar writings. General John J. Pershing, commander of the entire American war effort, devoted less than a page of his two-volume account of the war to the impact of influenza.[58] The pandemic of 1918 was one of the worst diseases in history, but for American military leaders on land and sea, it was a secondary enemy. No matter how bad the situation became, Germany was always the predominant concern, and every effort against the virus had to be subordinated to winning the war.

This downplaying of the virus reflected, in part, the Navy’s and the U.S. government’s efforts to maintain morale in spite of the crisis. The press was discouraged from causing undue concern (by the Wilson administration’s definition of “undue”), and the Navy followed suit by refusing to give the press too much information that might be detrimental to the war effort. The Army officer tasked with overseeing the health of personnel at American shipyards assured the Associated Press that the “so-called Spanish influenza is nothing more or less than old fashioned grippe.” Federal and state public health officials echoed this sentiment, assuring readers that there was nothing at all to be overly alarmed about. Even what reporters knew did not make its way unfiltered to the public. Wartime frequently brings with it reductions on freedom of the press, but no war in American history saw stricter censorship—voluntary and otherwise—than the Great War.[59] Newspapermen were used to shading the truth and casting every event in the most rousing patriotic terms possible. Thus, when it came to covering a plague sweeping through the nation at the height of the war, the press “reported on the disease with the same mixture of truth and half-truth, truth and distortion, truth and lies with which they reported everything else.”[60]

Naval Training Station, San Francisco, California. Crowded sleeping area extemporized on the Drill Hall floor of the Main Barracks, with sneeze screens erected as a precaution against the spread of influenza. Photographed during World War I, probably in the latter part of 1918. Signs on the wall at left forbid spitting on the floor. (NH 41871)

Of course, for Americans living in Philadelphia, Chicago, or anywhere else ravaged by the virus, journalistic downplaying of the situation fooled no one. The same was certainly true for those in the Navy confronted directly by the impact of the pandemic. American naval forces operating with the British in the North Sea did not need Sims, Pershing, or any journalist to tell them the pandemic was a crisis. By November, Royal Navy Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman reported that the British Grand Fleet was experiencing seven deaths per day; one British vessel lost 18 men. At least two British battle cruisers became functionally useless due to the number of men aboard incapacitated by the disease, and many other ships were badly undermanned. Among the American battleships, Arkansas (BB-33) suffered an outbreak that left over 250 men stricken and 11 dead, and Rodman had to postpone badly needed gunnery practice for his ships despite the fact that they still consistently underperformed their British counterparts in accuracy and rate of fire.[61] British and American officers alike nervously watched for the German fleet to come out for battle, having long hoped for just such an event but now fearful the fleet’s ravaged manpower would leave it at risk if a major naval battle were forced on it.[62] No such battle ever took place. In late October, when the outcome of the war was no longer in doubt, German admirals did briefly plan for a desperation assault on the Allied fleet, but an entirely different epidemic had swept through their ranks by the time they were ready to strike. German sailors succumbed to war-weariness and mutiny, flatly refusing to engage in a pointless expedition.[63]

It was fortunate for those Germans that their mutiny was successful, for had they attacked the fleet at that late stage of the war, they would have met an enemy enjoying very real progress fighting back against its epidemic. Thanks to rigid adherence to rules of quarantine, the Grand Fleet managed to achieve a measure of diminution of influenza. The severity of the outbreak on Arkansas did not spread to other ships, so Florida (BB-30) could miraculously report no cases, and only a single man was lost to the flu on New York (BB-34).[64] While desperate attempts to develop a vaccine or cure were proving fruitless, the world did find ways to mitigate the virus’s impact and slow its spread. Even if such efforts never lived up to the population’s hopes (and certainly not their wishes), they did keep the death toll from becoming even worse and helped pave the way for the second wave of the virus to run its course by the end of the year.

• • •

Americans were urged to avoid crowded spaces, especially poorly ventilated ones, steer clear of infected persons, and maintain good hygiene.[65] As the 1918 pandemic grew worse, stricter measures were put in place. Across the country, local governments banned large gatherings and mandated the use of masks. In addition to public information campaigns to encourage proper cleanliness and sanitation, those who engaged in behaviors that risked spreading the disease could face legal consequences, including heavy fines for spitting on the sidewalk. Some cities passed ordinances against handshakes. Even in the areas most severely impacted, such measures generated opposition. At a time when Philadelphia was suffering thousands of deaths every day, a writer at the Philadelphia Inquirer complained that while “crowds gather in congested eating places and press into elevators and hang to the straps of illy-ventilated street cars, it is a little difficult to understand what is to be gained by shutting up well ventilated churches and theatres.” The only possible answer must be that “authorities [are] going daft.” In truth, shutting down churches and theaters did seem to have no impact at all on the spread or mortality rate of the virus, but city officials across the nation were desperate to find any measures at all that might contain the disaster, and so strict closures remained in place.[66]

In their efforts to combat the pandemic, local officials repeatedly turned to nearby military facilities for assistance, and everywhere there was a naval station there was a substantial role for the Navy to play in helping surrounding towns. For many naval officers stationed in the United States, the line between aiding local governments and taking over their jobs became blurry. In Vallejo, California, the city adjacent to the Mare Island Navy Shipyard, a Navy corpsman had essentially taken over management of the overwhelmed local hospital. By 30 October, the situation had become so dire that a delegation met with the city council and demanded that “the entire situation [be] placed under the command of CAPT Harry George to be handled by his medical forces.” The relationship between the city and the navy yard was already close, although George canceled all liberty into the city as soon as the first patient at the yard was hospitalized. Still, naval personnel continued to take part in vaccination programs at local schools, and medical officers at Mare Island continued to provide counsel to the city government. By late October, it was obvious more help was needed. The city council did not go quite as far as the delegation demanded, but it did send a long overdue appeal to George for greater assistance. Two days later, another temporary hospital opened, almost entirely staffed by naval personnel.[67]

In Philadelphia, the city government was thoroughly unprepared to deal with the crisis, having atrophied under shameless corruption and machine politics for years. Officers operating out of the Philadelphia navy yard tried to exert pressure on the mayor’s office to do more, and one Philadelphia doctor wrote to the Navy’s Surgeon General, William C. Braisted, and essentially asked the Navy to declare martial law in the city. Braisted refused to endorse such a request, but the Army and Navy did agree to cease drafting doctors from Philadelphia and to hold off on calling up those few who had been drafted but had not yet left the city. In short order, federal intervention was rendered unnecessary when the leading families of Philadelphia decided to take charge of the situation. Under the auspices of the local Council of National Defense, the men and especially the women boasting the most prestigious bloodlines all but seized control of the city government, and despite the rather undemocratic character of the takeover, Philadelphia’s handling of the crisis soon saw marked improvement. There was only so much they could accomplish, however, and the disease continued to ravage the city until it had run its natural course.[68]

From transport ships to naval stations to the front lines of the war at sea, American naval officers desperately tried to protect their stations from outbreaks. Such efforts were no guarantee, however. Even the most scrupulous captains sometimes witnessed the virus hammer his vessel.[69] Dealing with the virus usually fell under the responsibility of the local commanders, and there was little in the way of a uniform, Navy-wide effort at stopping the disease’s progress. Still, most places followed similar patterns. Liberty was restricted, especially to towns facing serious outbreaks.[70] Across the Navy, there was a continual emphasis on cleanliness and proper hygiene. The demands of wartime often took precedence over this, of course, but the pandemic served to drive home the importance of keeping spaces sanitary.[71]

For the Navy’s medical personnel, service in the Cruiser and Transport Force meant being surrounded by the virus constantly during voyage after voyage, and stopovers in port, whether in Europe or back in the U.S., were usually brief and devoted to preparing for plunging back into the same conditions again on the next transatlantic crossing. After the war, Secretary Daniels singled out these men for particular praise.[72] Their heroic service, and enforcement of quarantining and mitigation efforts, did bear fruit, even under conditions where at least some spreading was inevitable. Transport ships contained the virus by “rigidly” enforcing regulations for “the continual wearing of gauze coverings over the mouth and nose, except when eating.” Although difficult given the number of men aboard ship, officers worked to ensure everyone as much time in the open air on deck as possible. In some cases, these efforts yielded impressive results. On the same cruise that saw over 500 cases on its second day at sea, George Washington managed to arrest the spread and achieve a remarkable reduction in the number of new cases by the time it reached France—although 77 men did not survive the voyage.[73] Thanks to careful attention to standard methods of containing the virus, the troop transports managed to keep the virus from getting completely out of control. By the end of the war, these ships had earned an enviable record in controlling the virus—being aboard a transport ship was actually safer than living in the worst-impacted cities or Army encampments.[74] After the war, Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, who had commanded the Cruiser and Transport Forces of the Atlantic Fleet, calculated a total of 789 influenza deaths aboard his ships, with a roughly six percent mortality rate among those who became infected. While tragic, considering the conditions the force had to work under Gleaves was justly proud at what the ships under his command accomplished, which he credited to scrupulous medical procedures as well as a rigid attention to cleanliness.[75]

In some ways, the U.S. Navy, and its Army counterpart, made gains combatting the virus at the home front’s expense. Even before influenza struck, the government had known the war effort would require an enormous influx of medical personnel, and in the spring of 1917, the best and brightest of America’s doctors and nurses had been inducted into the service. In most areas, the military had already claimed one out of every three or four doctors and nurses by the time the pandemic hit. In the early months of the war, the military had also done a good job selecting the most skillful, most qualified of the medical profession for the service, leaving behind a great many whom the Council of National Defense rated as incompetent. Even—especially—in the worst days of the pandemic, the military’s desire for nurses was insatiable. Yet no matter how many nurses they added to their ranks, Army and Navy facilities seemed just as overwhelmed as civilian hospitals when the number of cases peaked. At one Army encampment, desperate parents and sweethearts offered bribes to nurses to ensure their loved one received treatment.[76]

For those in the medical field, treating the infected carried enormous risks. Despite the best sanitation efforts, it was impossible to spend hours every day surrounded by infected patients without jeopardizing one’s own health, and the dead inevitably included many in the medical field. With the Navy suffering a disproportionate impact from the virus, Navy nurses were naturally among the most vulnerable. Josie Brown at the Great Lakes naval training station escaped the worst wave in the fall of 1918, but influenza finally caught up with her during the spring 1919 wave. “I ran a temperature of 104º or 105º for days; I just don’t remember how many days,” she recalled. Her symptoms obvious, doctors did not bother formally diagnosing her with the flu; they just did what they could to keep her alive. Placed in a curtained-off area of the hospital for sick women, Brown had her head, neck, and chest covered in ice and waited out the disease. “My heart pounded so hard that it rattled the ice; everything was rattling, including the chartboard and bedsprings,” she remembered.[77]

Brown survived, but the pandemic inevitably took its toll on nurses. In Philadelphia, Emma Snyder was among the first to look after the Navy’s Sailors who were hospitalized. Within days, she was dead, her life cut short at 23 years. A hospital in Boston had so many of its nurses fall sick that it flatly refused to accept any new patients. The Red Cross rushed a dozen additional nurses to alleviate the situation, but almost immediately the flu struck down eight of them, and eventually killed two.[78] With the Navy at the forefront of the pandemic, it was inevitable that the Navy’s nurses would be among the dead. All told, 32 Navy nurses died from the pandemic. Three of these nurses were posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for their service.[79]

The crisis of the 1918 pandemic prompted a massive effort from the American medical community to find some form of treatment that could reduce the impact of the virus, and the Navy was one of the leaders in this effort. Among the most celebrated men commissioned into the Navy at the start of the outbreak was Paul A. Lewis, who became a lieutenant commander in 1918 at the age of 39. Widely recognized as one of the most brilliant young medical scientists in the world, Lewis had already identified the virus that caused polio and developed a vaccine that had been proven to cure the disease in monkeys. Now he turned his attention to influenza. Working out of the Philadelphia navy yard and University of Pennsylvania, Lewis threw himself into researching the pandemic. Most of his efforts were directed toward finding a vaccine or serum that could be proven effective against the disease. In this, he was never entirely successful. Yet, Lewis continued working even after the pandemic ended and he returned to civilian life. His research contributed to the discovery by his protégé Richard E. Shope that influenza was caused by a virus. Lewis did not live to see this finding confirmed, however—his research in infectious disease eventually cost him his life. He died in 1929 in Brazil when he contracted the virulent strain of yellow fever he had come to study.[80]

In addition to large-scale experimentation by Lewis and others, Navy doctors across the country, and beyond, experimented on a smaller scale to try and reduce the number of sick and dying. At the naval hospital in Washington, D.C., doctors used blood from patients who made quick recoveries to produce a so-called immune serum. It seems to have been effective. A staggering one out of every four patients that contracted pneumonia were dying by the time doctors began administering the serum, but of the 46 patients with pneumonia who were treated with the serum, only three died.[81] Transports also became the site of experimentation. Lieutenant W. F. McNally of the Navy Medical Corps worked with 100 patients over a six month period. He found success in having the sick gargle a medicinal solution regularly and also vaccinated patients with a bacterin made from mild strains of the virus. He was forced to concede, however, that the small sample size, incomplete records, and inability to conduct lab work limited the usefulness of his studies.[82] These results were certainly promising, and no doubt the survivors whom McNally treated were extremely grateful, but it was never possible to test the serum in a more rigorous fashion. Systematic efforts to practice medical science aboard transports were rare. Wartime functions took precedence even over treating the pandemic, and postwar studies of the effectiveness of various efforts to use vaccines and serums found inconclusive results. In his comprehensive analysis of the pandemic, Jordan conceded that efforts such as those discussed above were “apparently of benefit in some cases,” but none offered “convincing evidence of general therapeutic efficacy.”[83] Despite the best efforts of American medical science, and despite a myriad of different vaccines and serums developed at scattered locations nationwide, no general treatment was ever found; the 1918 pandemic ended on its own timetable rather than on medical science. That said, recipients of experimental treatments developed at the local level on ships and stations across the country likely took a less clinical attitude than Jordan. Many of them could, with good reason, credit serums and vaccines with their survival. While Lewis and countless others like him regretted never finding a general cure during the pandemic, each person who survived—whether from experimental treatments or merely doctors and nurses offering the best medical care they could amid the circumstances—represented one small victory over the pandemic.

• • •

The pandemic did not depart with the war. Although the second, most severe wave had run its course by Christmas 1918, another wave struck in the spring of 1919. The final wave was less severe but still exacted a terrible toll, and indeed, the second wave that preceded it is really the only possible standard by which it can be compared favorably.[84] In fact, the third wave had a higher mortality rate for those who came down with it, but enough of the world’s population had immunity by that point that the actual number of dead was smaller.[85]

The third wave had repercussions for world events beyond just the number of dead. While taking part in the peace negotiations in Paris, President Wilson’s longtime adviser, Edward M. House, contracted influenza for the third time. Wilson himself came down with it in the midst of peace talks, and it may have contributed to his willingness to concede to virtually all of Britain’s and France’s demands. In October of 1919, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke that left him unable to function as president for the rest of his term. His wife and closest advisers concealed his condition from the public until he left office, but he was little more than a figurehead for the last three months of his second term. Whether his stroke was an aftereffect of influenza is impossible to say with certainty, but doctors did find strong evidence that the strain of influenza that caused the pandemic frequently led to long-term cognitive damage in survivors, including a marked increase in the number of Parkinson’s disease cases throughout the 1920s. The final year of Wilson’s administration, and his dreams of a merciful peace for Germany, may have been among the 1918 pandemic’s last victims.[86]

For the Navy, the third wave struck just when it was scrambling to bring two million Americans home from Europe. The return of virtually the entire American Expeditionary Forces was completed in a remarkably short time, with the job mostly done by the end of September. At its peak, the Cruiser and Transport Force was returning over 300,000 men every month. The most immediate result of this was that medical personnel knew they would be among the last to demobilize. As for the passengers, living conditions became more noteworthy than influenza for the return trip. Wartime necessity of course meant that most were willing to accept overcrowded and unpleasant conditions for the journey over. For the return trip, officers and men eager to get back home willingly signed up for extremely crowded ships that were sailing immediately, only to gripe almost as soon as they were at sea about living accommodations.[87] That did not mean the flu was nonexistent. Thirty-three men died of pneumonia resulting from influenza over nine voyages by Leviathan, but this was still a dramatic drop from the fall, when the same ship had once recorded 31 deaths in a single day.[88]

The recurrence of influenza forced the Navy to recall several nurses who had been deactivated and to keep nurses in place who had originally volunteered only for the duration of the war. Unlike the fall wave, when Navy hospitals were completely overwhelmed, there were enough nurses in place for the spring wave that patients (and healthcare workers) endured “under less trying conditions” than had been in place at the height of the pandemic. Navy-wide, the impact of the 1919 wave was similar to that of the world as a whole—serious, but tame compared to the horrors of the previous fall.[89]

By mid-March, the third and final wave had peaked and begun its decline. Although survivors had good reason to fear it would return, nothing like the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 ever came back. The year 1920 was still very bad for the flu, recording either the second- or third-most influenza-related deaths of the century, depending on which sources one consults. Even by then, however, the virus had mutated into a less severe form, and by that point a massive swath of the world’s population enjoyed immunity to this particular strain.[90] This likely helps explain the relatively mild impact of the spring wave on returning troop transports—a great majority of those being ferried back home had already been exposed to the virus on the journey over or during their time in Europe.

• • •

Although overshadowed in history and in memory by the global war it coincided with, the 1918 pandemic had left its mark on society in a major way. For the United States, roughly 675,000 died, and for the world, the death toll was anywhere from 20 to 50 million, though more recent studies place it even higher than that. Just the raw numbers of dead fail to tell the whole story. While the pandemic was at its height, the American Actuarial Society estimated that, given how many were cut down in the prime of life, the flu shaved an average of 25 years off its victims’ lives, with the loss of some 10 million years of human life in the United States alone. Such numbers are, of course, speculative, but more concrete are the financial costs to American life insurance companies. Nearly every life insurance company in the country suffered heavy losses, and one estimated that the number of claims during the worst period in October was over seven times what had occurred the previous year.[91]

For the Navy, historians estimate that some 40 percent of personnel came down with influenza at some point during the pandemic. The final body count for the Navy was officially 4,158 dead out of 121,225 admitted for symptoms (a 3.4 percent mortality rate).[92] Identifying the exact number of victims is an imprecise science, particularly for a pandemic as widespread as this one. At least one person who lived through it recognized this fact. Brown survived her bout with influenza and went on to a career in nursing. Decades later, she still recalled the dreadful things she witnessed, but not how many bodies the Great Lakes naval station sent away. “I suppose no one knows how many died,” she told a later interviewer; “they just lost track of them.”[93]

─Thomas Sheppard, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, September 2020

_______________________________________________

[1] James F. Armstrong, “Philadelphia, Nurses, and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918,” Navy Medicine 92, no. 2 (March–April 2001): 16–20, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/philadelphia-nurses-and-the-spanish-influenza-pandemic-of-1918.html; John G. M. Sharp, “The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Naval Training Station Hampton Roads and the Norfolk Naval Hospital,” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), Washington, DC, 27 April 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/g/the-great-influenza-pandemic-of-1918-at-the-norfolk-naval-shipyard-naval-training-station-hampton-roads-ad-the-norfolk-naval-hosptial.html.

[2] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html; (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22148/).

[3] Edwin O. Jordan, Epidemic Influenza: A Survey (Chicago: American Medical Association, 1927), 63, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/f/flu/8580flu.0016.858/--epidemic-influenza-a-survey?view=toc.

[4] Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 59.

[5] William S. Sims to Anne H. Sims, 29 June 1918, Box 10, William S. Sims Papers (WSS), Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (LC), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/june-1918/vice-admiral-william-68.html.

[6] Henry B. Wilson to William S. Sims, 7 July 1918, Entry 520, Box 440, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC (NARA).

[7] Hugh Rodman to Josephus Daniels, 8 June 1918, Entry 520, Box 381, RG 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC and College Park, MD (DNA), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/june-1918/rear-admiral-hugh-ro.html; Rodman to Daniels, 29 June 1918, Entry 520, Box 381, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/june-1918/rear-admiral-hugh-ro-2.html.

[8] Albert P. Niblack to Sims, 3 June 1918, Entry 520, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/june-1918/rear-admiral-albert.html; Niblack to Sims, 10 June 1918, Entry 520, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/june-1918/rear-admiral-albert.html.

[9] Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1919 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1920), 2195.

[10] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 23–33; John Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 109–110, 148–150.

[11] Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994), 420.

[12] Barry, Great Influenza, 91–97; Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 23–24.

[13] Barry, Great Influenza, 92, 454–456; Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 27–28.

[14] Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 60–64, 73–76; Jeffery K. Taubenberger, “The Origin and Virulence of the 1918 ‘Spanish’ Influenza Virus,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 150, no. 1 (March 2006): 90.

[15] Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 76.

[16] Barry, Great Influenza, 455.

[17] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 23–33; Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 97; Capt. Thomas L. Snyder, “The Great Flu Crisis at Mare Island Navy Yard, and Vallejo, California.” Navy Medicine 94, no. 5 (September–October 2003): 25–29, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/great-flu-crisis-at-mare-island-navy-yard.html.

[18] Barry, Great Influenza, 171.

[19] Nathan C. Twining to Daniels, 21 May 1918, Entry 517B, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/may-1918/captain-nathan-c-twi.html.

[20] Barry, Great Influenza, 176. Barry acknowledges this theory exists, but rejects it.

[21] Barry, Great Influenza, 177–178.

[22] H. W. Brands, Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 119–121.

[23] William C. Braisted to Daniels, 7 September 1918, Roll 47, Josephus Daniels Papers, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/september-1918/surgeon-general-of-t.html.

[24] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 43–49.

[25] Barry, Great Influenza, 333.

[26] Barry, Great Influenza, 238; Taubenberger, “Origin and Virulence,” 90.

[27] Barry, Great Influenza, 365.

[28] Barry, Great Influenza, 238–240.

[29] Barry, Great Influenza, 200–202.

[30] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 73–80; Barry, Great Influenza, 197–205, 220–224.

[31] Rogue River Courier, October 1918, quoted in Sharp, “Pandemic at Norfolk.”

[32] R. M. Kennedy, “Influenza at the U.S. Naval Hospital, Washington D.C.,” United States Medical Bulletin 13, no. 2 (1919): 355, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/influenza-at-the-united-states-naval-hospital-washington-d-c.html.

[33] “New Orleans, Louisiana,” Influenza Encyclopedia, accessed August 2020, http://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-neworleans.html.

[34] “St. Louis, Missouri,” Influenza Encyclopedia, accessed August 2020, http://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-stlouis.html; Meagan Flynn, “What Happens if Parades aren’t Cancelled during Pandemics?,” Washington Post, 12 March 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/03/12/pandemic-parade-flu-coronavirus/.

[35] Francis Buzzell, The Great Lakes Naval Training Station: A History (Boston: Small, Maynard and Company, 1919), 7–8.

[36] Josie Brown, interview by Rachel Wedeking, “A Winding Sheet and a Wooden Box,” Navy Medicine 77, no. 3 (May–June 1986), 18–19, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/a-winding-sheet-and-a-wooden-box.html.

[37] Quoted in Barry, Great Influenza, 202.

[38] Snyder, “Mare Island Navy Yard.”

[39] Personal Account by William B. Caperton of the 1918 Influenza on Armored Cruiser No. 4, USS Pittsburgh, at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, NHHC, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/admiral-william-b-caperton-of-the-1918-influenza-on-armored-cruiser-no-4-uss-pittsburgh.html.

[40] Annual Reports, 2096.

[41] Frank P. Glass, The Birmingham News, et al. to Woodrow Wilson, 9 October 1918, Box 24, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/frank-p-glass-chairm.html.

[42] Sims to William S. Benson, 11 October 1918, Box 49, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/vice-admiral-william-2.html; Sims to Sims, 15 October 1918, Box 10, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/vice-admiral-william-36.html.

[43] Kathleen M. Fargey, “The Deadliest Enemy,” Army History 111 (Spring 2019): 30.

[44] Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1968), 83–84.

[45] Simsadus, “General Bulletin No. 11,” 2 November 1918, Box 24, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/november-1918/staff-of-vice-admira.html.

[46] Albert Gleaves, A History of the Transport Service: Adventures and Experiences of United States Transports and Cruisers in the World War (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1921), 190.

[47] Robert J. Wallace to Crosby, 10 February 1970, in Forgotten Pandemic, 129–131.

[48] John T. Cushing and Arthur F. Stone, Vermont and the World War, 1917-1919 (Burlington, VT: Free Press Printing Company, 1928), 6, quoted in Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 131.

[49] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 131.

[50] Coffman, War to End All Wars, 81–84; Gilbert, First World War, 520.

[51] Lisle A. Rose, America’s Sailors in the Great War: Seas, Skies, and Submarines (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2017), 190.

[52] William N. Still, Crisis at Sea: The United States Navy in European Waters in World War I (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2006), 217–221.

[53] Arthur J. Hepburn to Simsadus, 28 September 1918, Entry 530, Box 413, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/september-1918/captain-arthur-j-hep.html; Charles P. Nelson to Sims, 26 October 1918, Box 75, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/commander-charles-p-2.html.

[54] Niblack to Sims, 18 October 1918, Box 24, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/rear-admiral-albert-0.html; Niblack to Sims, 29 October 1918, Box 76, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/rear-admiral-albert-1.html.

[55] Sims to Sims, 26 October 1918, Box 10, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/vice-admiral-william-14.html; Gilbert, First World War, 479.

[56] Still, Crisis at Sea, 224.

[57] Sims to Daniels, 17 October 1918, Entry 517B, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/october-1918/vice-admiral-william-6.html; Twining to Benson, 29 November 1918, Box 49, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/november-1918/captain-nathan-c-twi.html.

[58] William S. Sims, The Victory at Sea, Classics of Naval Literature (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1984), originally published in 1920; Josephus Daniels, Our Navy at War (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1922); Josephus Daniels, The Wilson Era: Years of War and After, 1917–1923 (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1946); John J. Pershing, My Experiences in the World War (New York: Frederick A. Stokes and Company, 1931), 2:327–328.

[59] David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 25–26; A. Scott Berg, Wilson (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013), 453–455.

[60] Barry, Great Influenza, 334–341.

[61] Rodman to Sims, 2 November 1918, Entry 520, Box 381, RG 45, DNA, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/november-1918/rear-admiral-hugh-ro-0.html.

[62] Jerry W. Jones, U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 68–69.

[63] Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 773–776.

[64] Rodman to Sims, 2 November 1918; Simsadus, “General Bulletin No. 12,” 5 November 1918, Box 24, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/november-1918/general-bulletin-12.html; Jones, U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I, 68–69.

[65] Directive from Washington, D.C. regarding treatment and procedures, 26 September 1918, RG 181, National Archives, New York, NY, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/records-list.html.

[66] Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 October 1918, quoted in Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 77. For another perspective on the effectiveness of closures, see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862334/.

[67] Snyder, “Mare Island Navy Yard.”

[68] Barry, Great Influenza, 202, 322–332.

[69] Henry B. Price to Sims, 9 November 1918, Box 79, WSS, LC, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/documentary-histories/wwi/november-1918/captain-henry-b-pric.html.

[70] Still, Crisis at Sea, 220.

[71] 1919 Annual Reports, 2194, 2207.

[72] 1919 Annual Reports, 108–109.

[73] Gleaves, Transport Service, 190–191.

[74] Benedict Crowell and Robert Forrest Wilson, How America Went to War: The Road to France (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1921), 2: 445.

[75] Gleaves, Transport Service, 190–191.

[76] Barry, Great Influenza, 216, 318–320.

[77] Brown, interview.

[78] Barry, Great Influenza, 187, 202, 204.

[79] Naval History and Heritage Command, “Influenza of 1918 (Spanish Flu) and the U.S. Navy,” https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/influenza-of-1918-spanish-flu-and-the-us-navy.html.

[80] Barry, Great Influenza, 1–4, 200–201, 281–287, 443–447.

[81] Kennedy, “Washington Naval Hospital.”

[82] W. F. McNally, “Influenza on a Naval Transport,” United States Naval Medical Bulletin 13, no. 1 (1919): 168–170, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/i/influenza/influenza-on-a-naval-transport.html.

[83] Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 303–304; see also Barry, Great Influenza, 358–359.

[84] Barry, Great Influenza, 374.

[85] Jordan, Epidemic Influenza, 107–108.

[86] Barry, Great Influenza, 378–386.

[87] 1919 Annual Reports, 111.

[88] Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1920 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1921), 755; Crowell and Wilson, Road to France, 445.

[89] 1920 Annual Reports, 745, 939–940.

[90] Barry, Great Influenza, 390–391.

[91] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 298.

[92] Crosby, Forgotten Pandemic, 121; Influenza of 1918 (Spanish Flu) and the U.S. Navy.

[93] Brown, interview.