Attacking the U-Boat: The North Sea Mine Barrage

In the history of the United States Navy, World War I is considered a model of combined operations. The Navy worked closely with its allies, especially with the British Royal Navy. American naval units merged with their British counterparts to form commands that appeared seamless and models of unity and cooperation. Yet, tensions remained, and the North Sea mine barrage is a manifestation of this.

There were those among the leadership of the U.S. Navy, including Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William S. Benson, who believed that the British strategy in combating the German U-boat campaign was “lethargic and essentially defensive.”1 The American leadership instead advocated an aggressive policy: attacking the U-boats in their home ports, or, if that was infeasible, preventing U-boats from reaching the high seas where detection and destruction were difficult. Thus, the idea for the North Sea mine barrage was born.

The Americans actually proposed the idea of a barrage a few days after this country’s entry into the war. The British Admiralty, however, firmly rejected it. In the months that followed, the Americans repeatedly advanced the scheme, and the British (supported by the American commander in European waters, Vice Admiral William S. Sims) just as repeatedly rejected it.

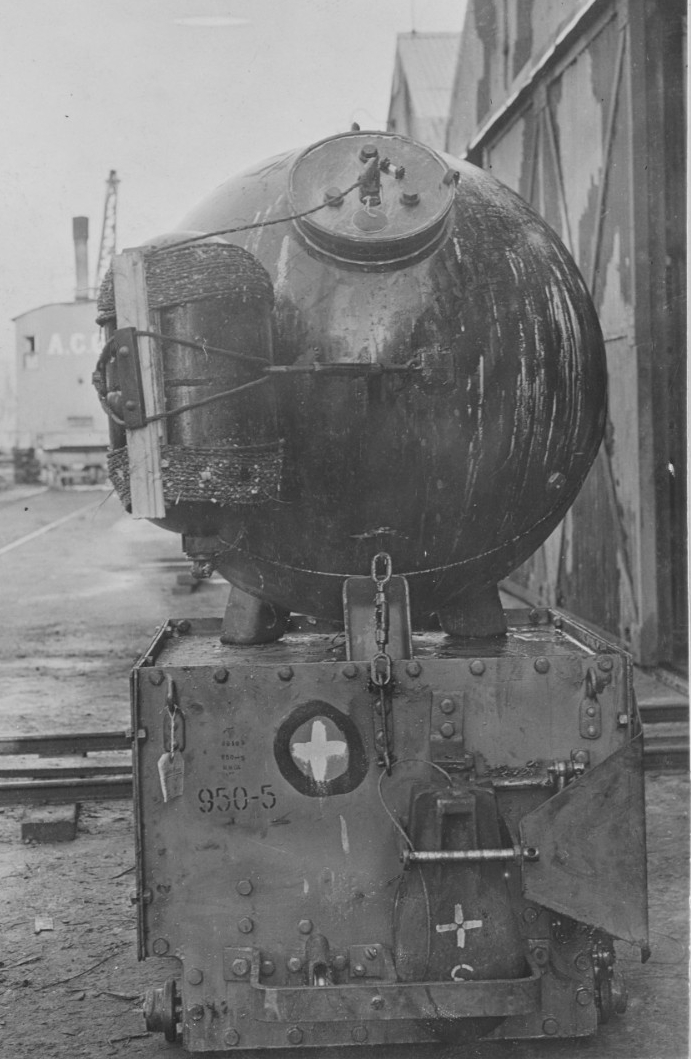

Finally, in the autumn of 1917, the British began at least to entertain the idea of a barrage. The impelling factor was the development by the Americans of a mine, the Mark VI, “peculiarly adaptable for use against submarines.”2 Also, as the British were seeking more and more resources from the Americans, it was good to appear to value their key naval ally’s opinions. As a result, when Admiral Alfred T. Mayo, the commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, led a Navy mission to England in September 1917, the British gave the barrage what Mayo considered to be qualified approval: If the U.S. provided the mines and skilled personnel to assemble them, the British would cooperate.

__________

1 Dean C. Allard, "Anglo-American Naval Differences During World War I," Military Affairs, No. 44 (April 1980), 78.

2 “Commander Simon P. Fullinwider, USN, to Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, USN, 17 December 1918,” Simon P. Fullinwider Papers, Smithsonian Institution, Museum of American History, Division of Military History and Diplomacy, Washington, DC.

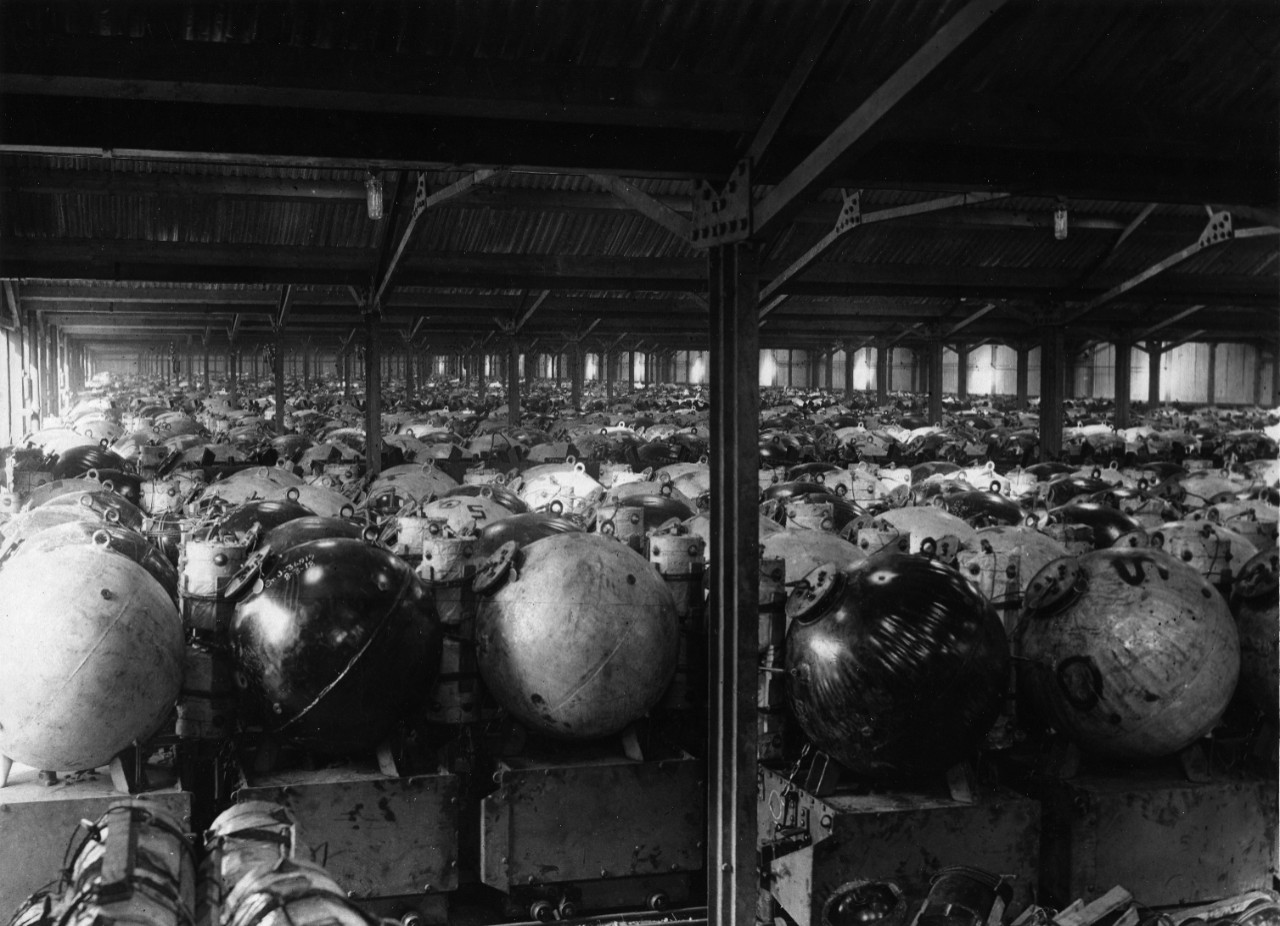

Manufacturing the mines was done in the best American mode. The mine was divided into seven constituent parts, each according to a separate and standardized design, and then each of those parts was assigned to a different manufacturing facility, including a number of automobile factories that could produce only a limited number of cars during the war and so had excess capacity. From these factories, the parts were shipped to a mine-loading plant at St. Juliens Creek, near Norfolk, Virginia, where they were loaded on a fleet of 24 mine-carrying ships, landed on the western coast of Scotland after the Atlantic passage, and then shipped by rail to the final assembly facilities at Bases 17 and 18 in Invergordon and Inverness, Scotland. Two of the mine carriers left the U.S. each week and made the round trip is some two months’ time. The process became so efficient that producing 1,000 mines per day was easy and roughly 4,000 were shipped each week.3

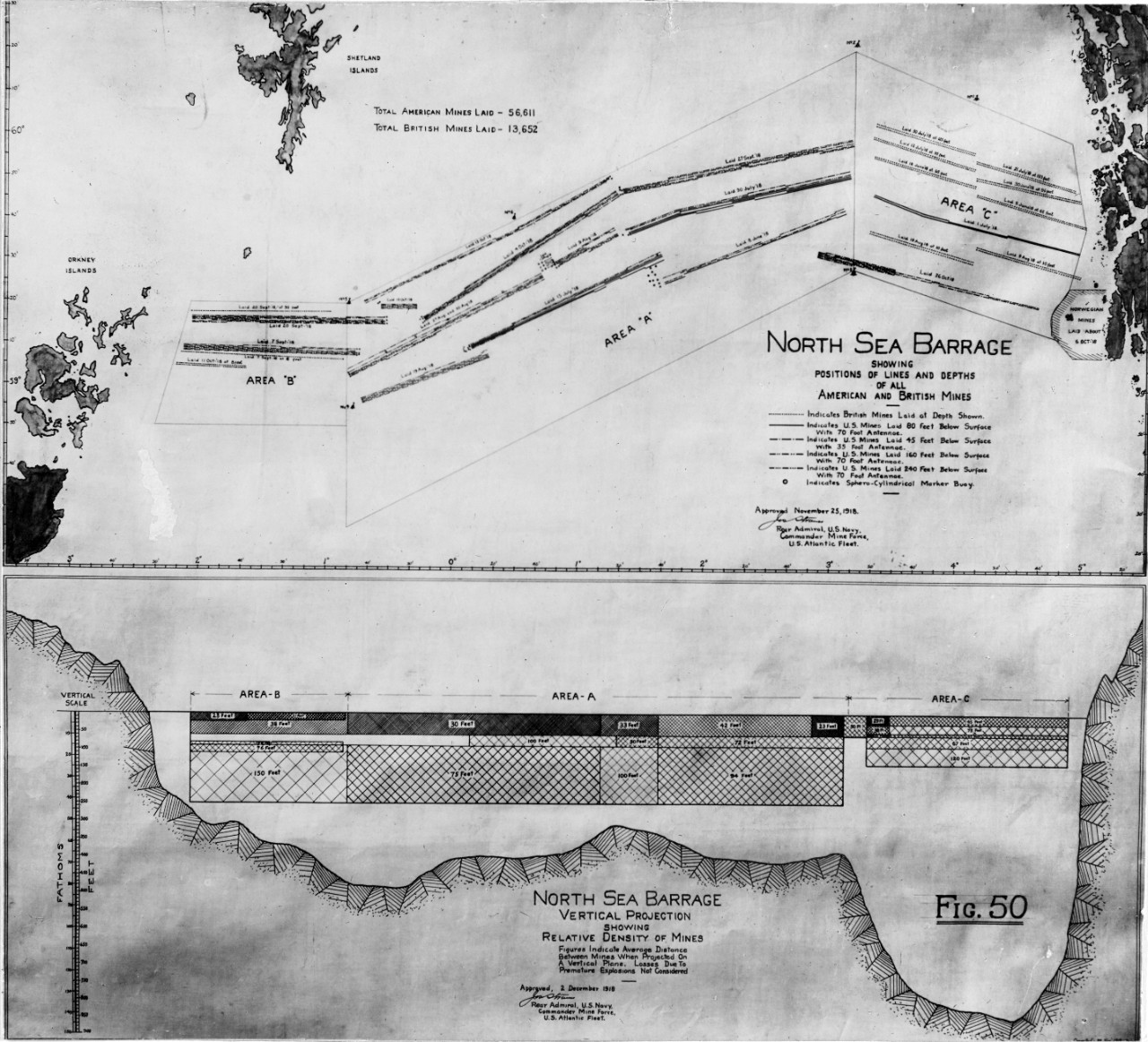

Production at such a rate was necessary because the scope of the project was equally impressive. The North Sea barrage, laid on an axis extending from Aberdeen, Scotland, to Ekersund, Norway, totaled “10,000 tons of TNT, 150 shiploads of it, spread over an area 230 miles long [the approximate distance from New York to Washington, DC] by 25 miles wide and reaching from near the surface to 240 below—70,000 anchored mines each containing 300 pounds of explosive.” It took five months and 15 expeditions, starting on 8 June, to lay down the barrage.4

__________

3 Historical Section, Navy Department, The Northern Barrage and Other Mining Activities (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 53–58.

4 Captain Reginald R. Belknap, USN, The Yankee Mining Squadron or Laying the North Sea Mine Barrage (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1920), 17.

The men who created this mine barrier were unsung heroes. They overcame a number of issues, most notably the difficulty getting sufficient numbers of personnel for this service. According to Rear Admiral Daniel Mannix, then a lieutenant commander commanding one of the minelayers, volunteers were few because the mines were filled with a “new and terrible explosive” (TNT), which terrified many, and because Navy men disliked minelaying on principle, referring to it as “rat-catching,” and observed that in battle you might surrender but if a mine on a minelayer exploded “you made a hole in the water that…took three months to fill up.”5

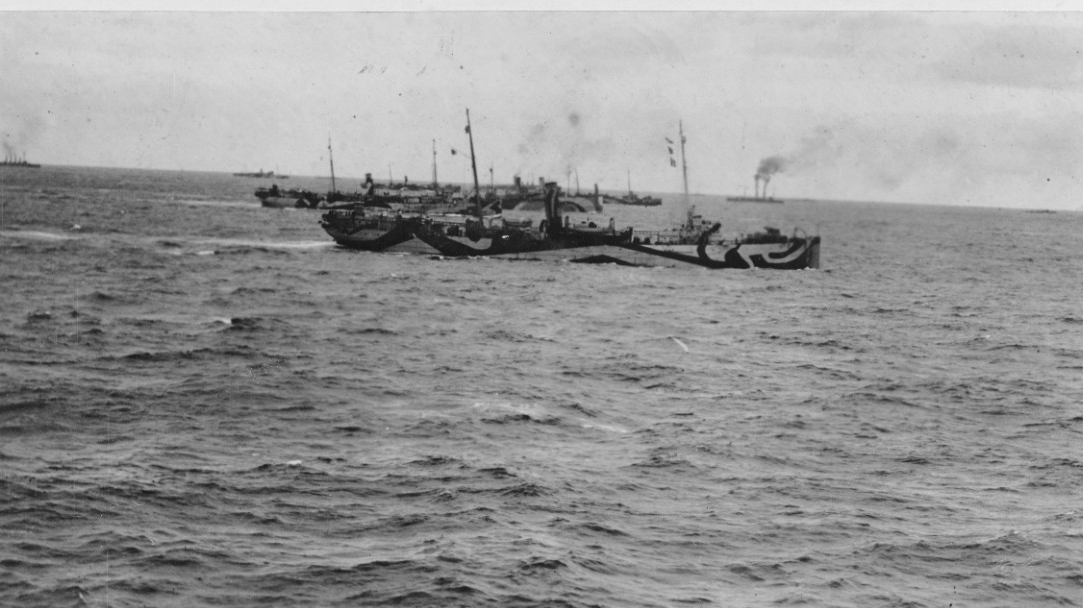

Despite this, the crews worked efficiently and well. Runs varied from 46 miles on the first expedition to over 60 on subsequent trips and lasted approximately two days. During these runs, the number of mines laid varied according to the availability and requirements, but the numbers were always impressive. On the tenth expedition, for example, 5,520 mines were planted in 3 hours and 50 minutes.

___________

5 Rear Admiral Daniel P. Mannix III, USN (Ret.), The Old Navy (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983) 221.

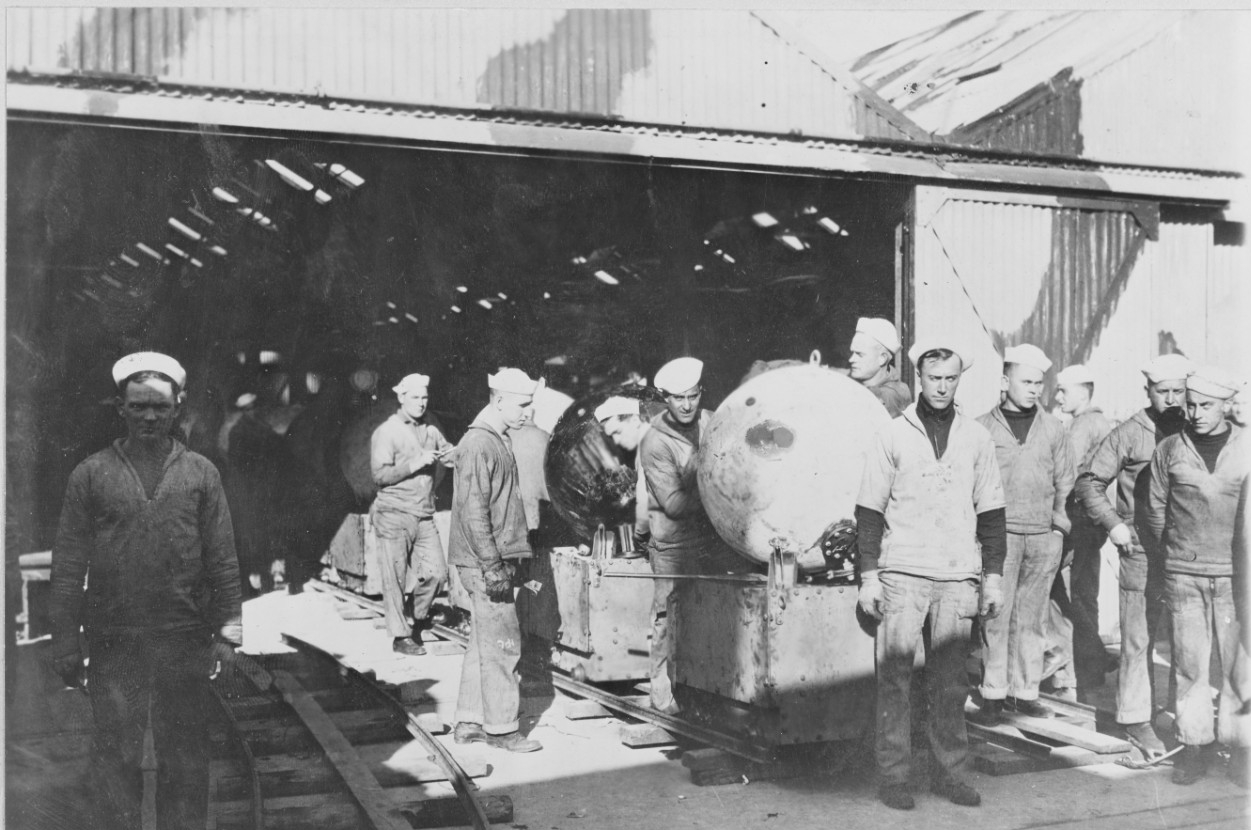

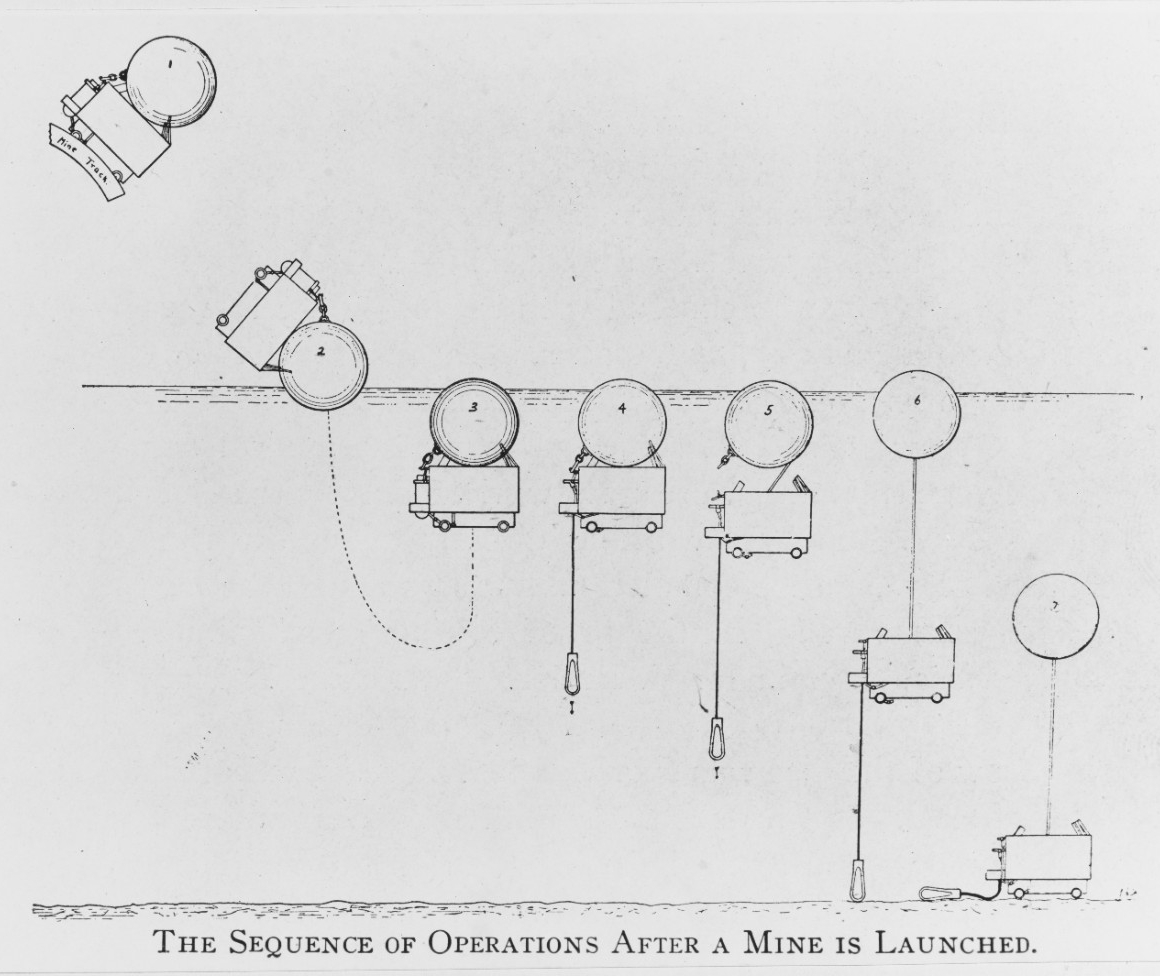

The mines were lined up on rails, the number depending on the size of the minelayer, and were pushed manually toward the “barn door” opening in the stern of the launching deck. As a compartment emptied, the doors to it closed, and doors on another compartment opened, the moveable section of mine track adjusted, and the mines in that compartment were hauled out. When a planter had dropped all its mines, another planter steamed alongside and quickly took its station. On average, the planters dropped a mine every four to twelve seconds and the entire drop took four to seven hours.

This feat was accomplished despite the fact that equipment was substandard.6 The flagship of the squadron was a former cruiser built in 1890. USS Quinnebaug (S.P. 1687) was a typical minelayer: a “frail” old ex-merchantmen with “completely shot” engines.7 On at least two occasions, Quinnebaug’s cargo deck spontaneously burst into flame because the ship’s ventilation system did not work well enough to remove gas fumes.8

The weather and sea conditions could be abysmal. Fog, recalled one officer, was a “major problem,” but “we handled that pretty well, keeping in formation by means of towing spars and very skillful handling of ships.”9 The expeditions also encountered high winds, rain, and rough seas.

There was also the ever-present danger of a German attack. The minelayers dodged torpedoes and German mines while wondering when the German fleet might sally against them.10 Always in the back of their minds was the question that should one of the minelayers be torpedoed with mines aboard and “blown to atoms, would the explosion detonate mines on the other ships and all of them go up together?” Luckily, that question was never answered.11

__________

6 Belknap, Yankee Mining Squadron, 46–48.

9 John P. Corrigan, Tin Ensign: Mine Planting in the North Sea (New York: Exposition Press, 1971); William N. Still, Jr., Crisis at Sea: The United States Navy in European Waters in World War I (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2006), 440.

Were all this work and bravery worth it? In other words, was the barrage effective and worth the cost? Secretary of the Navy Daniels was confident that it was. He wrote that “not laying the barrage earlier—in fact, at the earliest possible moment—was, in my opinion, the greatest naval error of the War.” And, although the cost was huge, it was less than the cost of “an average month’s loss of shipping” to submarine attack and “less than the cost of a single day of the war as a whole.”12 Historians are not so sure. The best estimate is that six German submarines were destroyed and that it affected the morale and efficiency of the German submarine service. However, other historians have argued that the resources spent on the barrage would have been more profitably used elsewhere. In the end, the question can never be determined definitively because the barrage was still unfinished when the war ended: The Norwegians had not yet mined their territorial waters, leaving the Germans a path through the minefield to open sea.13

Finally, it should be remembered that just as the barrage was nearing completion the war ended and those 70,000 mines had to be cleared. For the next 11 months, the Navy worked on removing the mines and successfully did so with another herculean effort, which is detailed elsewhere on this site.

—Dennis Conrad, Ph.D., Histories Branch, Navy History and Heritage Command, May 2018

__________

12 Quoted in Ernest K. Lindley, Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Career in Progressive Democracy (Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1931), 160.

13 Still, Crisis at Sea, 443.

For Further Reading

Belknap, Captain Reginald R., USN. The Yankee Mining Squadron or Laying the North Sea Mine Barrage. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1920.

Historical Section, Navy Department. The Northern Barrage and Other Mining Activities. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920.

Mannix III, Rear Admiral Daniel P., USN (Ret.) The Old Navy. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983.

Corrigan, John P. Tin Ensign: Mine Planting in the North Sea. New York: Exposition Press, 1971.

Still, Jr., William N. Crisis at Sea: The United States Navy in European Waters in World War I. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2006.