Final Voyage Home

The Return of the Unknown Soldier

Since his interment, the Unknown Soldier of World War I has become a powerful symbol—for remembrance, for solidarity, for understanding, and for reflection. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a marble sarcophagus with the remains of three unidentified service members that rests within the nation’s most hallowed grounds, represents many things to Americans. It also means a great deal to the hundreds of thousands of visitors from foreign nations that make the journey to Arlington National Cemetery every year. Honoring fallen heroes from any military resonates with much of humankind. However, many Americans do not know that the U.S. Navy played an important role in returning the Unknown Soldier to U.S. soil.

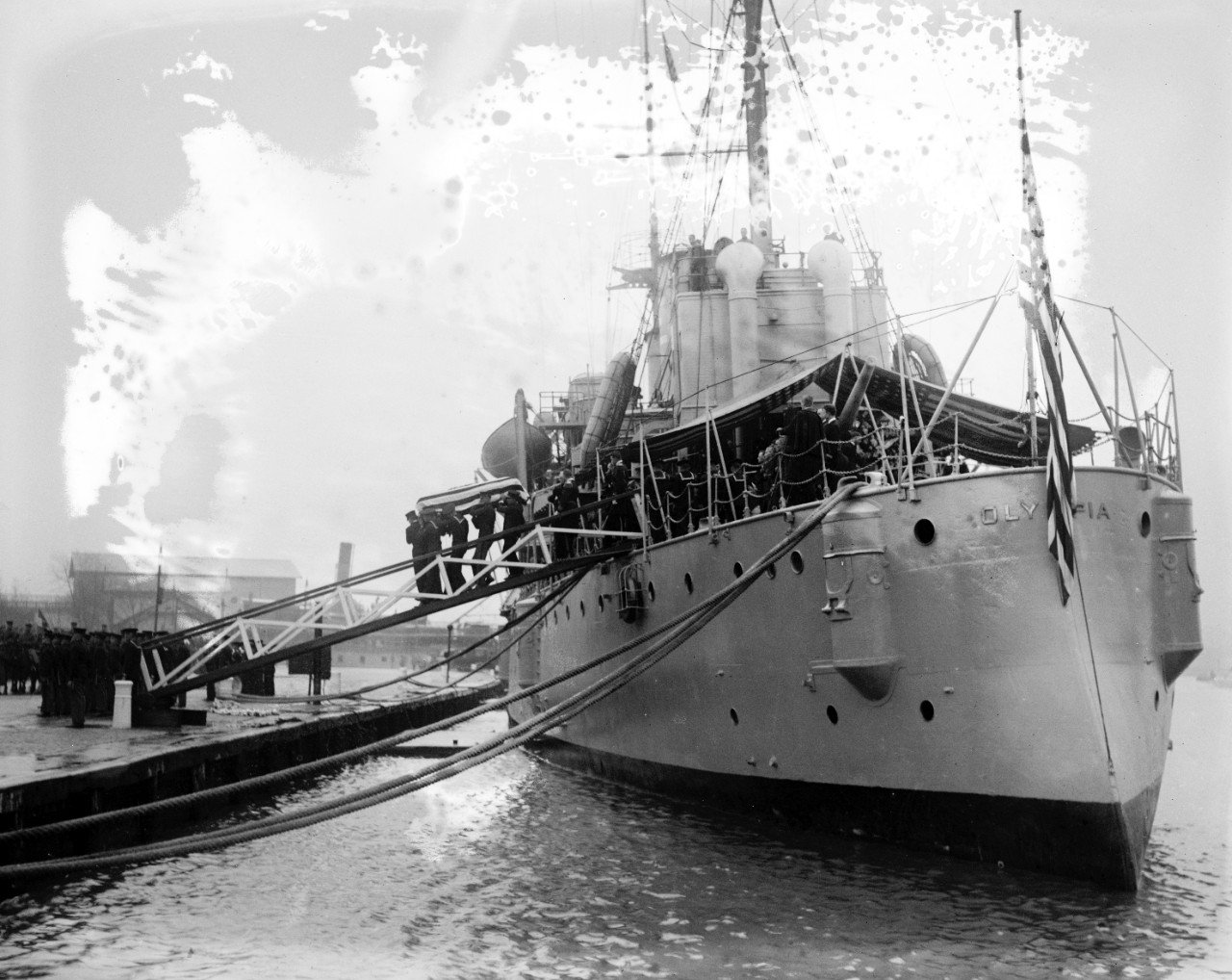

Navy involvement began after Congress “approved the burial of an unidentified American soldier from World War I in the plaza of the new Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery” on 4 February 1921.1 This meant that the country needed a vessel to transport the unidentified soldier from France across thousands of miles of open Atlantic Ocean. The Navy assigned this mission to USS Olympia (CL-15). Almost eight months after the congressional resolution, Olympia departed from her homeport in Philadelphia and began the long voyage to the French coast.

On Memorial Day 1921, Sergeant Edward F. Younger, a member of Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry, U.S. Army, stood in a large city hall in Châlons-sur-Marne, France. He had been wounded twice during the recent conflict and had also been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for combat valor. Younger, at that time serving with the Army of Occupation in the German Rhineland area, had been chosen to select the Unknown from four caskets. There was no reference to race, creed, or rank. The remains in front of him were identical, unmarked, and unnamed. Younger walked solemnly around the caskets and then chose the third from his left, marking it with a bouquet of white roses.

Olympia arrived in port Plymouth, England, on 14 October, in time to provide full honors to the Unknown Warrior of Britain, and for her crew to assist in the ceremony through the streets of London that ended at Westminster Abbey. After drilling and parading on 17 October and recognizing another nation’s fallen brother, the crew returned to the ship and left six days later for Le Havre, France, to continue their primary mission.2

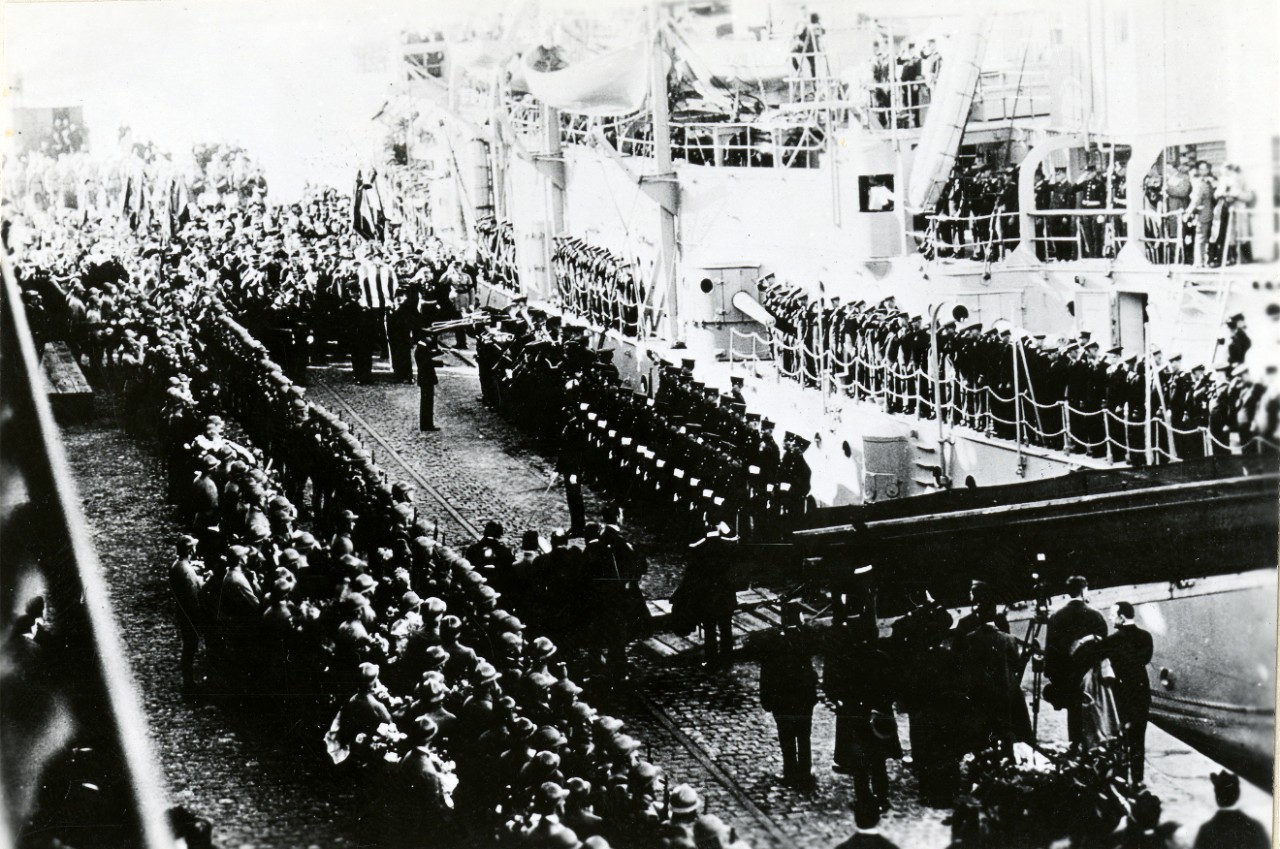

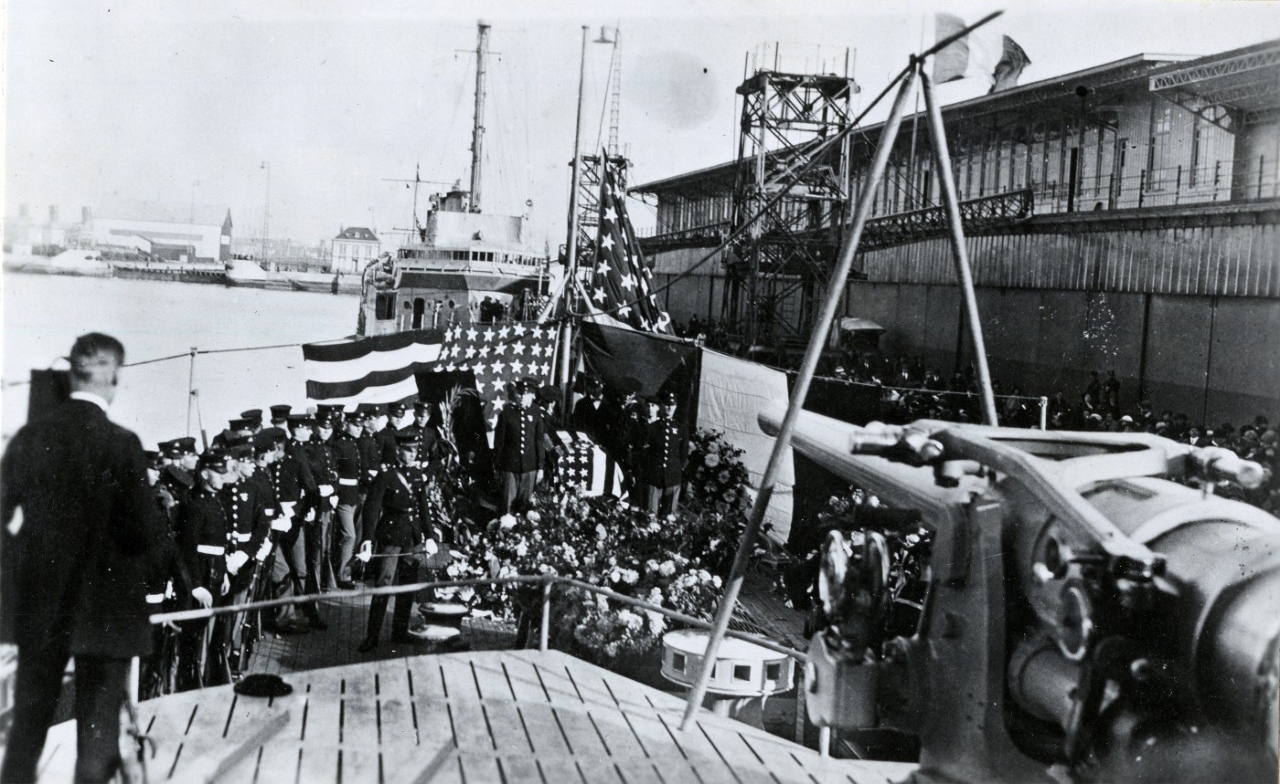

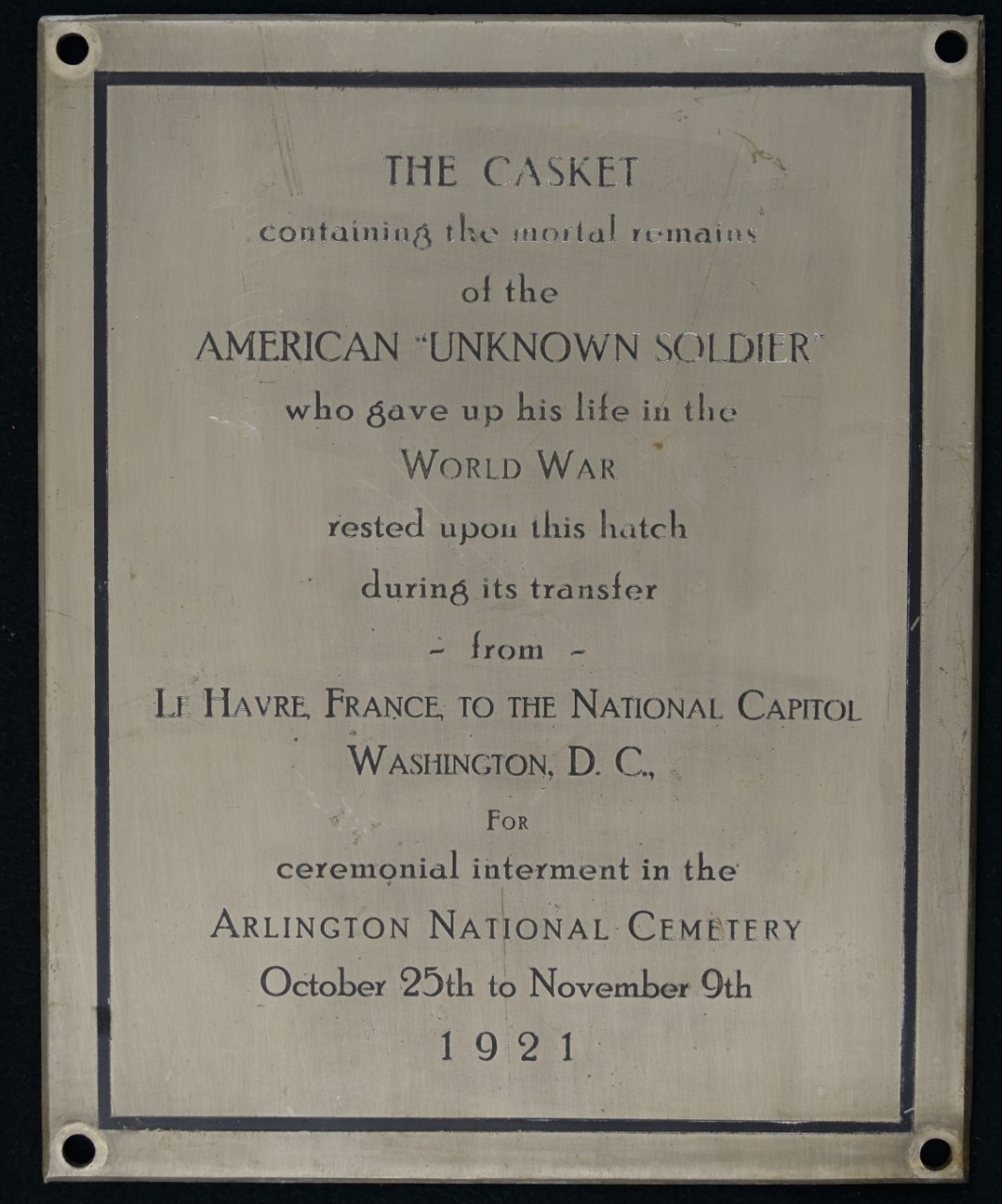

The transfer of the Unknown Soldier to the Olympia followed with much fanfare. The crew stood at the ready at 2:20 in the afternoon of 25 October.3 When the Army detail bearing the Unknown Soldier got near the gangway, it was relieved by six Sailors and two Marines from the ship’s company. The men walked up the gangway and set the casket on the deck of the heavily decorated stern, surrounded by a sea of flowers. Remarkably, a box of earth removed from the battlefields of France accompanied the Unknown on Olympia. It was intended to line the fallen American warrior’s grave.4 The casket was too large to be moved below and was secured to the deck. As a respectful send-off, French local officials, dignitaries, and even schoolchildren placed more flowers and wreaths all over the casket. The heaping piles eventually flooded the deck. When she was ready to depart, Olympia, with the stars and stripes at half-mast, began pulling away from the dock and was met by the destroyer USS Reuben James (DD-245) for a full escort into the open waters. Six French naval vessels following closely port and starboard.5

Unfortunately, the 14-day passage was not easy. The remnants of multiple hurricanes made travel on the high seas perilous. Heavy waves, high winds and turbulent rain threatened the crew and the ship. The honor guard, a detachment of 38 Marines led by Captain Graves B. Erskine, risked their lives to stand watch and protect the remains of the Unknown. Because of the intense weather, which caused endless work for the ship’s stokers keeping the boilers fueled, Olympia burned through over 950 tons of coal to cross the Atlantic, leaving only 63 tons of coal left in her bunkers when she reached Washington Navy Yard, her final destination. The restless Atlantic was calm again as the vessel reached the eastern shore of Virginia on 7 November, offering the crew some relief after the perilous crossing allowing them to prepare the ship’s schedule for the upcoming ceremony.

The cruiser moored downriver from her destination, the Washington Navy Yard, on 8 November. Destroyers USS Crowninshield (DD-134), USS Barney (DD-149), USS Blakeley (DD-150), USS Bernadou (DD-153), and the veteran battleship USS North Dakota (BB-29) joined the historic flagship to escort her up the Potomac River. Olympia made her way into the Anacostia River, then known as the Eastern Branch, to get to the Washington Navy Yard.6 Pier 3 was selected as the best location for off-loading the casket. High-ranking and well-known military and civilian officials, including Secretary of the Navy Edwin Deby and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Robert Coontz, were present. The gray, overcast skies with a slight drizzle of rain made it seem as if the weather had adapted to the somber event. Sections of rope hit the aft deck as the crew carefully unlashed the casket and removed the waterproof canvas cover from the top of the custom-made housing. The Associated Press reported that

Along her rails stood her crew in long lines of dark blue, rigid at attention and with a solemn expression uncommon to the young faces beneath the jaunty sailor hats.... At attention stood five sailors and marines as guards of honor for the dead at each corner and the head of his bier. Just as the ship's bell clanged out the quick, double strokes of “eight bells” the sailors' four o'clock and the hour set for arrival, the bugles rang again and the crew again lined the rails far above the dock.7

The remains were lifted out of the transit box, hoisted onto the shoulders of the bearers, and steadily carried down the gangway. The boatswain lifted his small metal call to his mouth and piped the Unknown “over the side,” a standard honor for outgoing high-ranking officers now bestowed on this icon. The Navy and Marine bearers transferred the casket to a detachment from the Army’s 3rd Cavalry Regiment.8 The entire ceremonial movement of the Unknown from the deck of the ship to the awaiting caisson lasted a total of six minutes.9 Records do not identify the sailors and Marines who removed the casket from Olympia nor the detachment of other military personnel that lifted and escorted the Unknown Soldier to the Capitol Building. It appears that officials decided to omit their names from the record to maintain anonymity, allowing the casket to be the focal point of the story.

Lines of U.S. Navy sailors marched in the procession through the streets of downtown Washington, DC. They followed the caisson as it made its way out of the Navy Yard, traveled west on M Street, northwest on New Jersey Avenue, and held fast in the shadow of the dome of the Capitol Building. While the Unknown Soldier lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda, Navy personnel were part of the Honor Guard standing watch at the catafalque, the same plinth that had previously held the caskets of three assassinated presidents. Situated at each corner, one Sailor, one Marine, one Soldier, and one National Guardsman stood at attention next to the casket.10 After one day of standing watch and seeing almost 100,000 mourners, sailors joined the honor cordon, arranging themselves just outside the main doors of the Capitol. Two Navy chief petty officers, Chief Gunner’s Mate James Delaney, in charge of the Armed Guard aboard troop transport SS Campana, and Chief Water Tender Charles Leo O’Connor, assigned to troop transport USS Mount Vernon (ID 4508), were selected as honorary body bearers by General of the Armies John J. Pershing. These men were part of the eight-person detail that carried the casket from the Capitol Rotunda, down the east staircase, and into the awaiting carriage. Three flag officers, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, Rear Admiral Charles Peshall Plunkett (who had commanded the Navy’s heavy railway artillery in France), and Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet Rear Admiral Henry B. Wilson, were appointed “honorary pallbearers” because of their service during World War I.

A contingent of bluejackets from the Washington Navy Yard, with members of the other three services, made up the Composite Foot Regiment and acted as the primary military escort for the five-mile procession. Following them were four clergymen, including Captain John B. Frazier of the Navy. The honorary pallbearers and the body bearers escorted the horse-drawn caisson. President Warren Harding walked alongside Pershing, Vice President Calvin Coolidge and CNO Koontz walked together, as did 27th President and current Chief Justice William H. Taft with Admiral Hilary P. Jones. Former President Woodrow Wilson’s carriage followed with multiple civilian and military formations that included one of 327 Medal of Honor recipients and another containing three service members from each U.S. state and territory.11 The Navy remained on point as the procession continued northwest on Pennsylvania Avenue and then north on 15th Street. It then headed west toward the White House, and around Washington Circle until reaching M Street. On M Street, the lead officials continued south over the Aqueduct Bridge, later rebuilt and called the Francis Scott Key Bridge, that connected Georgetown to Rosslyn, Virginia.12

The procession arrived at Arlington National Cemetery and made its way to the Memorial Amphitheater, where thousands of visitors awaited. The casket was placed on a plinth for the funeral ceremony. Onlookers patiently listened to the chaplains, stood for two minutes of respectful silence, heard the President’s address, watched as the foreign dignitaries bestowed the highest military awards on the Unknown, listened to the music of the military bands and sang hymns, and watched the pallbearers, including Delaney and O’Connor, set the Unknown on the vault to be steadily lowered into the ground.13 A field artillery detachment fired a 21-gun salute and the sole bugler played “Taps” to honor the fallen. The hero was laid to rest and “wrapped in the tender embraces of the flag which he gave his life in battle, the boy who through some village street had lightly marched away to war was home again.”14

The Unknown Soldier represents all members from every branch of service who made the utmost sacrifice. Unfortunately, the remains laid to rest on 11 November 1921 did not mark an end to future wars. The tomb, now filled with the remains of combatants from three American conflicts—World War I, World War II, and the Korean War—provides a site for reflection and remembrance just outside of the hustle and bustle of the nation’s capital. It represents a legacy of courage and a focal point for the somber acknowledgement of men and women who gave their all for their nation. In November 1921, the remains of an anonymous serviceman returned home. However, he was never truly unknown: he was claimed as a son, father, and brother by the entire nation.

To the Unknown Soldier: Thank you for your service! We honor you, stand by you, and we will continue the watch.

—Wesley R. Schwenk, National Museum of the U.S. Navy

____________

1 United States Congress, 66th Session, Public Resolution 67, 4 March 1921.

2 J. R. Neubiser, The Society of the Honor Guard, Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, “With the Hand of God He Will be Delivered Home.”

3 Ensign L. K. Cleveland, Record Group 24: Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007. Logbooks of U.S. Navy Ships, 1801–1940. USS Olympia 01/01/1921–12/31/1921. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA hereafter), Washington, DC. NAID 148844639, 482.

4 Maryland Independent (Port Tobacco, MD), 4 November 1921, 1.

5 “The Unknown Soldier of the World War,” RG 111, Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, H-1137. NARA, College Park, MD. 26 February 1936.

6 Lieutenant Junior Grade R. N. Wilder, Record Group 24: Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007. Logbooks of U.S. Navy Ships, 1801-1940. USS Olympia 01/01/1921–12/31/1921. NARA, Washington, D.C. NAID 148844639, 508–509.

7 Associated Press, “Body of ‘The Unknown Soldier’ Arrives Home,” Night Report, 9 November 1921, A.

8 Troops E, F, and G were present after being called in from nearby Fort Myer. A bier is a stand or frame on which a casket is placed to either lie in state or be transported to a gravesite before the funeral proceedings.

9 Lieutenant Junior Grade R. N. Wilder, Record Group 24: Records of Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007. Logbooks of U.S. Navy Ships, 1801–1940. USS Olympia 01/01/1921– 12/31/1921. NARA, Washington, DC. NAID 148844639, 510–11.

10 Associated Press, “Ceremonies at Capital and March to Cemetery, President Eulogizes Dead; Military Leaders, Supreme Court Justices and Members of Congress Participate in Funeral Procession,” Washington, DC, 11 November 1921.

11 “Order of Procession with Unknown Soldier,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), 10 November 1921, 1.

12 Mossman, B. C., and H. W. Stark, The Last Salute: Civilian and Military Funerals, 1921–1969 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army 1991).

13 “Funeral Ship Due at 4 P.M,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), 9 November 1921, 1–2. A vault is the mechanism used to lower a casket gently into the ground during burial.

14 “Ceremonies for Escort,” The Washington Times (Washington, DC), 10 November 1921, 10; “Hero Comes Home,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), 10 November 1921, 1.