Historical Summary of the U.S. Naval Railway Batteries

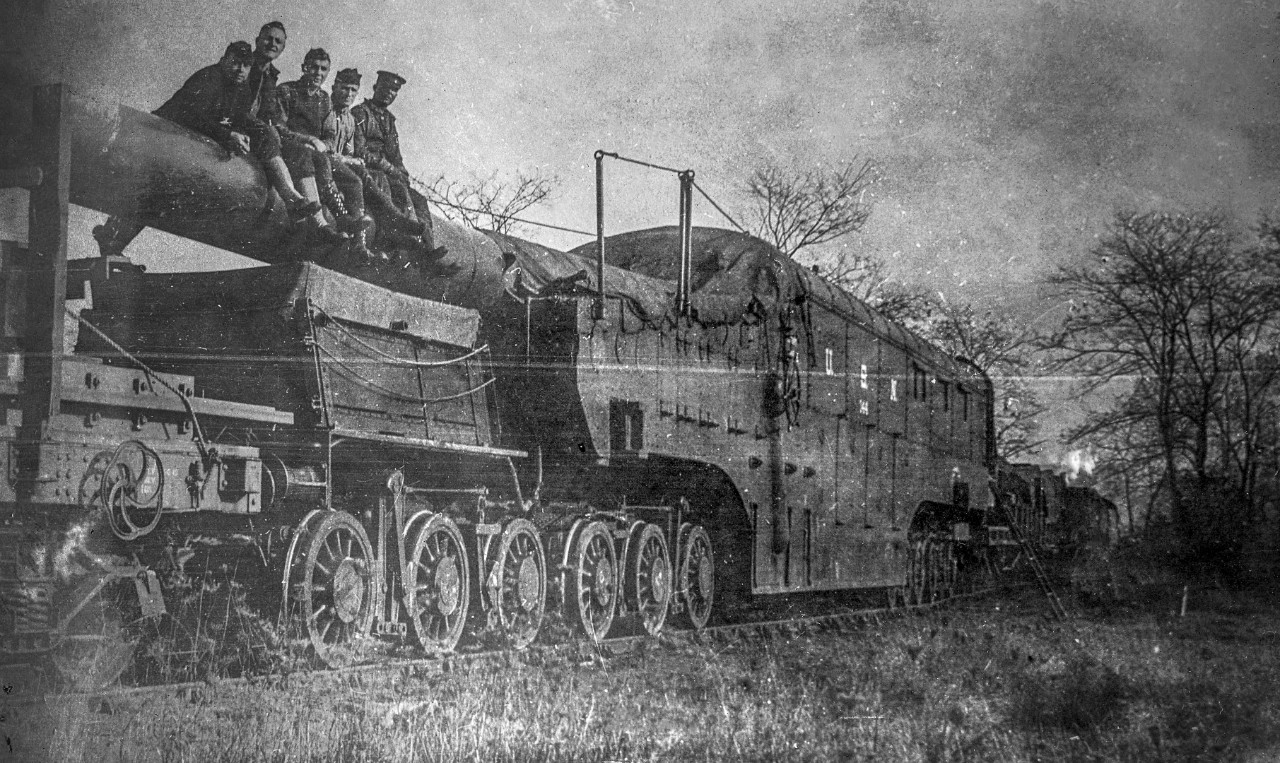

Artillery dominated the battlefields of Europe throughout World War I. Advances in artillery technology and design in the later 19th century had created a new generation of guns and howitzers with enhanced range and accuracy. At the outbreak of the war, however, none of the armies possessed railway guns, the idea for which was relatively new.[1] As the fighting on the Western Front solidified in the fall of 1914, military leaders realized the importance of mobile, long-range, heavy artillery for striking targets deep behind enemy lines. Constructed by the French army in late 1914, the first railway guns of the war were makeshift designs created by mounting older coastal defense guns and naval warship guns onto commercial railway wagons. British and German forces fielded railway guns in 1915 and 1916, respectively, increasing the range and firepower of their artillery. The U.S. Navy deployed five purpose-built railway guns in France during the final stages of the war, firing nearly 800 rounds in support of advancing American and Allied forces.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the Navy was already developing long-range artillery chiefly to counter the German army’s heavy guns capable of bombarding the English Channel ports used by the Allies. The Navy’s initial idea was to employ several 14-inch 50-caliber Mark IV naval rifles, with a complete train of equipment for each gun, on railway mountings behind British lines in France, but changing military conditions prevented British authorities from stating definitively at which port these batteries were to be debarked. The Navy then offered the guns to General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, who readily accepted them. Captain Charles P. Plunkett was assigned as commanding officer of the U.S. naval railway batteries, and he soon began assembling and training officers and enlisted personnel at three sites: the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, D.C.; the Naval Proving Ground in Indian Head, MD; and the Army proving ground in Sandy Hook, NJ. The first gun mount was complete and ready for firing on 25 April 1918; the last was ready four weeks later.

With Saint-Nazaire on France’s western coast as the designated port of debarkation, the U.S. naval railway batteries and their equipment were transported across the Atlantic in successive stages during the summer of 1918. The five batteries were assigned to the First Army’s Railway Artillery Reserve, but were organized to operate as independent units under the command of Plunkett (recently promoted to rear admiral) and his chief deputies, Lieutenant Commanders Garret L. Schuyler and Joel W. Bunkley. After successful field testing of Battery no. 2 near the village of Heilles, 37 miles north of Paris, the gun unit travelled in late August to the outskirts of Rethondes, near Compiègne, to bombard a railroad hub more than 20 miles away at Tergnier. Battery no. 1 completed field testing at Nuisemont, near Troyes, and went into action in early September at Soissons, bombarding railway yards in Laon some 21 miles away. The other battery units soon went in action near Verdun against German communication, supply, and transport centers along on the Metz-Sedan line.

Owing to the vast distances at which the naval batteries engaged their targets, first-hand battle damage assessments usually had to wait until after German forces had retreated from ground they had previously held. According to a subsequent account by then-Commander Joel W. Bunkley, “the shell craters of the 14-inch projectiles were easy to identify” when inspecting former targets of the batteries at Laon. “They differed from the holes made by the large bombs,” Bunkley explained, “in that they were deeper, larger, and of a remarkably uniform size... One shot was sufficient to completely wreck a railroad line of three tracks for a distance of one hundred yards, tearing up the rails, shattering the ties, and blowing an enormous crater in the roadbed.”[2]

While they operated well behind the front lines and were not subject to the constant bombardment received by more forward positions, the U.S. naval railway batteries were hardly immune from enemy fire. Many of the units took counter-fire from German artillery. German observation planes flew above their positions during the day, and bomber aircraft were active at night. The units lost only one Sailor to enemy fire, Shipfitter First Class A. P. Sharpe, who died on 29 October from injuries sustained in the explosion of a German shell near Thierville-sur-Meuse. Several other Sailors were wounded in the blast that killed SF1 Sharpe.

The U.S. naval railway batteries operated right up to the end of hostilities on the morning of 11 November 1918. Batteries 4 and 5 fired on German positions at Longuyon until minutes before the armistice went into effect at 11:00 a.m. In the weeks that followed, the five battery units, their guns, and auxiliary equipment travelled to Saint-Nazaire and Brest, the two main ports from which they would return to the United States. The vast majority of the officers and men arrived in New York by Christmas Eve. Their battlefield service in northern France during World War I is also explored elsewhere on this site:

and

Gregory Bereiter, Ph.D.,

Histories Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Bunkley, J. W. “The Woozlefinch: The Navy 14-Inch Railway Guns.” Proceedings 57.5 (May 1931): 584–598.

Bye, L. B. “U.S. Naval Railway Batteries.” Proceedings 45.6 (June 1919): 909–956.

Hogg, Ian V. Allied Artillery of World War One. Ramsbury: Crowood Press, 1998.

Marble, Sanders, ed. King of Battle: Artillery in World War I. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Naval Historical Center. The United States Naval Railway Batteries in France. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1988. Reprint.

Romanych, Marc, and Greg Heuer. Railway Guns of World War I. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Strong, Paul, and Sanders Marble. Artillery in the Great War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2011.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Confederate forces fielded an improvised rail-mounted artillery piece in 1862 during the American Civil War. The gun was a 32-pound naval rifle mounted on a flat railway wagon. Union forces subsequently built two guns similar in design to the Confederate model.

[2] J. W. Bunkley, “The Woozlefinch: The Navy 14-Inch Railway Guns,” Proceedings 57.5 (May 1931): 587–588.