USN Railway Batteries in World War I

World War I, the Great War, a war to end all wars. A phrase first coined by British author H. G. Wells in his collection of essays The War that will End War published in 1914. A theme that has reverberated through discourse on the war ever since. This first total war, “was [instead] an all-embracing conflict reaching far and wide across the continents. It premiered devilish new weapons and created new methods of mass slaughter.”[1]

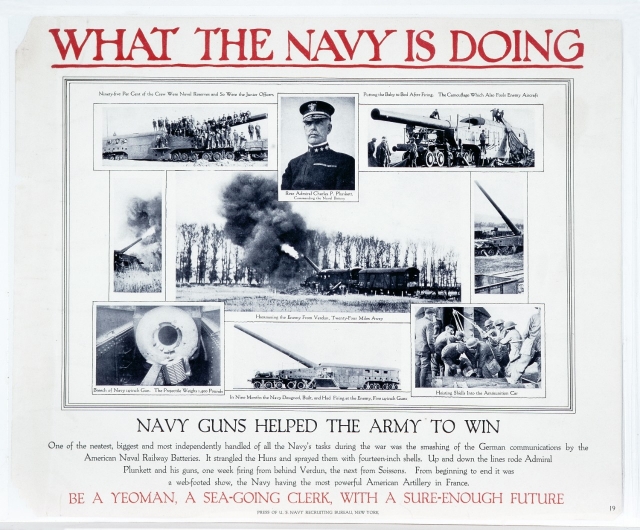

The United States of America entered the war in April 1917 unprepared and underequipped for the changing landscape of warfare which was evolving on the Western Front. “In the prewar army, the infantryman was a rifleman, nothing more and nothing less.” [2] “The United States Army was similarly lacking the other weapons ….. such as artillery, tanks, and aircraft.”[3] By the end of the war all the services were better placed to fight this type of newly mechanized warfare. The Navy’s contribution to the war effort is perhaps best known in the North Sea Mine Barrage, logistical support for the American Expeditionary Force, and offensive operations in the European theatre. The Navy also contributed to the development of long-range railway guns for use by the Allied forces.

By the beginning of World War I the Germans had developed sophisticated long range artillery such as; the Leugenboom guns that enabled them to bombard Dunkirk from a distance of over 24 miles. The bombardment lasted from April 28, 1915 until the army retreated in 1918. [4] The Allies needed to combat this initiative or suffer possible loss of the channel ports. Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, “became convinced that a way must be found by means of very powerful long-range naval guns not only to reply to the Leugenboom batteries but also to bombard the German supply and concentration positions behind the front.”[5] The batteries would need to be mobile and self-sustaining.

The solution was to mount a 14-inch 50 caliber Mark IV Navy Rifle onto a mobile mount in this case a railway carriage specifically designed to carry the gun and its slide. The 14 inch guns were readily available, developed for use on battle cruisers; a redesign of the ship left the guns available for use. [6] On November 26, 1917 the Navy Department approved the construction of five 14-inch railway mounts; the contract for the gun cars was awarded to Baldwin Locomotive Works Pennsylvania with the first mount being completed on April 25th 1918.[7] The Naval Batteries were commanded by Captain C. P. Plunkett (later Rear Admiral) and manned by crews of sailors.

The batteries consisted of officers and enlisted personnel to include:

1 commanding officer 1 aid 1 medical officer 1 supply and pay officer 1 clerk 5 battery officers 5 fire-control officers 5 gunners 5 machinists 5 chief gunner’s mates 15 gunner’s mates 5 carpenters mates first class |

|

16 assistant cooks and mess attendants 12 radio operators 1 hospital steward 6 hospital apprentices 6 firemen 6 trainmen 60 fire-control observers 35 seamen (gun crew) 115 general ratings. 11 cooks 5 blacksmiths 5 machinists’ mates’ first class |

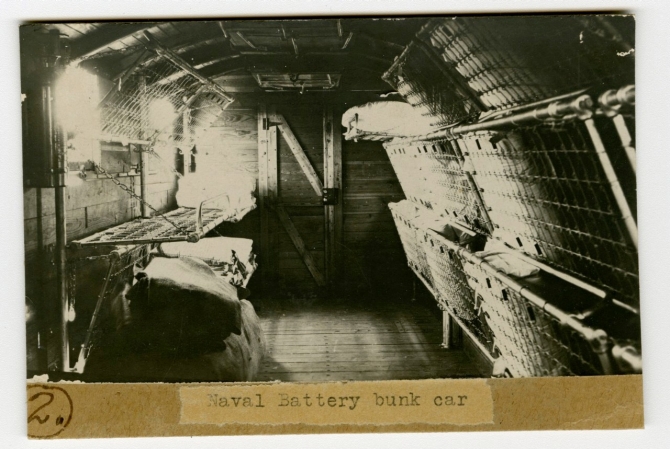

The batteries were supported by ammunition cars, auxiliary cars, and staff cars providing all necessary equipment for a mobile base.

The men were initially sent to the Naval Proving Ground Indianhead, Maryland, Naval Gun Factory, Washington DC and Sandy Hook Proving ground New Jersey to train how to; “put the guns in place, load and fire them, disassemble [them]…..They were [also] required to operate trains, operate locomotives, to[learn how to] build railway track.” [8]

The disassembled batteries were shipped to St Nazaire in France where they were reassembled by the battery crews. The first two trains of the original five commissioned by the Navy were ready for service on August 18th and 19th 1918. The batteries continued to operate until the Armistice was signed on November 11th 1918. The railway batteries were assigned to the Railway Artillery Reserve of the First American Army, and used in support of the war effort by both American and French forces. The RAR adopted the affectionate insignia the, “woozlefinch” or ozzlefinch. The insignia represented a “fictitious specimen that was neither flesh, fish nor fowl. This, from the fact that they were always needed at any time at any point along the front. Thus the batteries became five of the biggest “Woozlefinches” ever in existence.”[9]

The batteries were deployed to support ground offensives, bombarding the communication and supply networks of the Germans. “The fire was usually withheld until several hours after an Infantry attack…then bombard[s] the railway centers at a moment when they were the most crowded.”[10] The batteries were very effective not only as a demoralizing force on the overstretched German forces but tactically they achieved their goals. The batteries succeeded in cutting the main railroad communication and supply lines at Longuyon, Conflans and Montmédy. [11]

The sailors were not living in trenches, dealing with the same level of unsanitary living conditions that infantrymen endured. They were not subject to the same level and ferocity of bombardment that a front line position received, but their living conditions were spartan. The report by the Surgeon General of the United States Navy provides some interesting insights into daily life in the battery cars. Ventilation was an issue; the lumber used in the construction of the cars was shrinking as it cured causing gaps in the walls. “This was the cause of no little discomfort for frequently the bedding was wet from blowing rains.”[12] Lighting and heating were similar areas of concern with too few kerosene lamps and only one stove at the center of the car causing cold spots and uneven heating. Cleanliness was an issue with the ashes and coal dust from the stove, dugouts used by the battery crews were infested with lice.

The batteries although not situated on the front line did come under artillery fire and inadvertently mustard gas. Injuries did occur, at Soissons three American engineers, who were not Navy personnel were killed. Cars were derailed and on October 28th three men from Battery No 4 were wounded by enemy fire. Shipfitter 1st Class A.P. Sharpe U.S.N.R.F died as a result of his injuries.[13]

With the end of the war the United States naval batteries were disbanded at St. Nazaire. Property was transferred to the U.S. Army Quartermaster and the majority of the men were shipped home. 21 men and Lieutenant E. D. Duckett remained in St. Nazaire, to secure the guns for shipment back to the United States. These few remaining sailors finally left France on December 17, 1918.[14]

The advent of new technologies during the inter-war period negated the continued use and development of railway battery guns. Naval History and Heritage Command is fortunate to have in its collection one of the few surviving examples of a railway battery gun and mount. The battery serial number 148 is one of six Mk I mounts ordered by the Army after the successful Sandy Hook Proving Ground trials. The battery was completed in July 1918 and shipped to France. It was in the process of being reassembled when the war ended. The battery was returned to the United States in March 1919 and after a request from the Bureau of Ordnance was transferred to Dahlgren proving ground to be used in armor tests in 1922. The battery was transferred to NHHC in 1987 and incorporated into the Navy’s historical artifact collection. The current 14” gun barrel in the mount is a MK II Mod 0 and is not original to the mount.

The mount is a visual reminder of the ability of the Navy to be innovative, to problem solve, and under tight deadlines to successfully procure and implement a new programs. These skills would be tested again during World War II.

[1] Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War (New York : Oxford University Press 2013), page xx.

[2] Mark, Ethan Grotelueschen, The AEF Way of War: The American Army and Combat in World War I (New York: Cambridge University Press 2007), page 13.

[3] Ibid., page 13.

[4] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 1.

[5] Ibid., page 2.

[6] United States. 1918. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1918. Washington D.C.: [s.n.] page 47.

[7] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 6.

[8] Ibid page 6.

[9] Commander J.W. Bunkley, USN, “The Woozlefinch: The Navy 14 inch Railway Guns,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1931:584.

[10] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 18.

[11] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 6.

[12] United States. 1920. Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1920. Washington D.C.: [s.n] page 2086.

[13] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 21.

[14] Naval Historical Center (U.S), United States Naval Railway Batteries in France (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center 1988), page 90.