Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Largest Sea Battle in Modern History

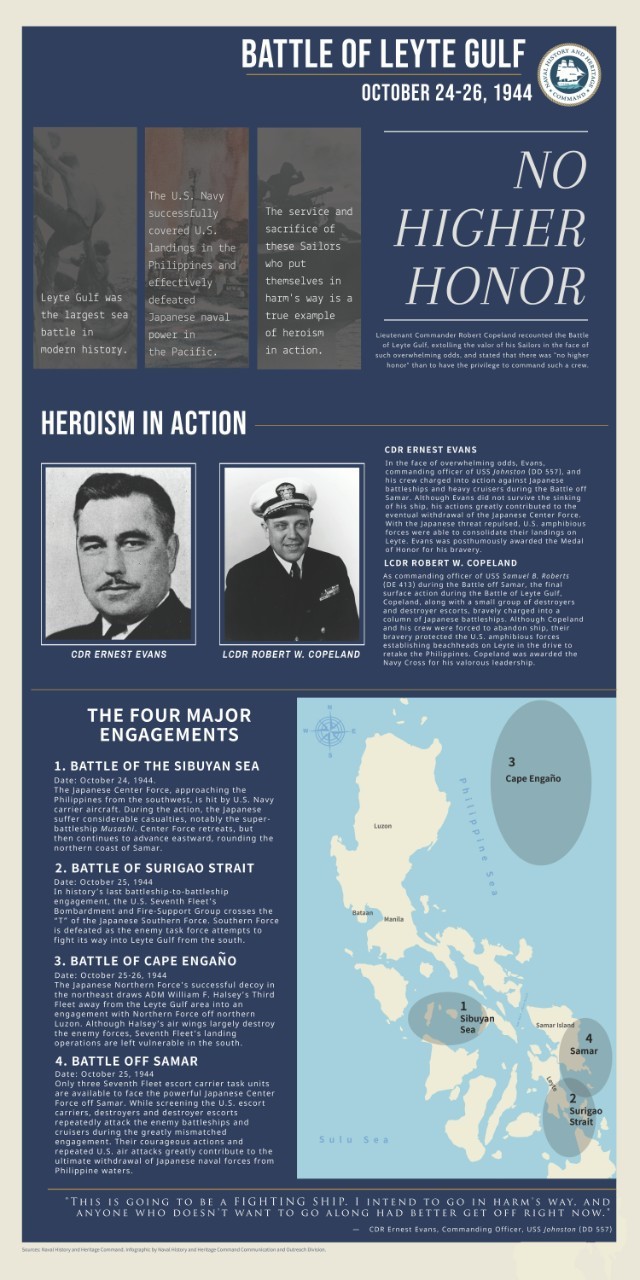

Recognized as the largest naval battle of World War II, the Battle of Leyte Gulf began on Oct. 23, 1944, with U.S. submarines attacking two elements of the Japanese armada moving toward Leyte. In the Palawan Passage, USS Darter (SS-227) and USS Dace (SS-247) sank heavy cruisers Maya and Atago. Takao was also attacked, but ultimately survived. In addition, off Manila Bay, USS Bream’s (SS-243) torpedoes heavily damaged Japanese cruiser Aoba. The Battle of Leyte Gulf, which lasted until Oct. 26, crippled the Japanese Combined Fleet, and consolidated the U.S. invasion of the Philippines and the Allies’ control of the western Pacific. The Battle of Leyte Gulf made good on Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s promise, “I shall return”: to retake the Philippines after it was lost to Japan in the early stages of World War II.

At this point in the war, the Allied goals in the Pacific were threefold: sever Japan’s supply lines to the East Indies; soften the battlefield for the invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) and the east China coast; and provide bases for an attack on the Japanese home islands. In early September, Adm. Marc Mitscher’s fast carrier task force began to launch attacks against Japanese positions in the Philippines. On Sept. 21, U.S. aircraft struck Manila for the first time and other targets on Luzon were attacked the following day. On Sept. 24, Mitscher’s air assets bombed the central Philippines and conducted photographic reconnaissance of the areas of Leyte and Samar where the initial Allied landings were planned. Originally, the massive attack on the Philippines was planned for a later date, but Mitscher’s airstrikes revealed unexpected weaknesses in the Japanese defense of the islands. The Joint Chiefs of Staff swiftly moved to capitalize on the Japanese vulnerability. The timetable was revised and an amphibious assault was scheduled for late October. Leyte was deemed vulnerable from the east and had great access to other islands in the archipelago. Moreover, the seizure of Leyte would isolate Japanese troops in Mindanao. The assault on Leyte also marked the merging of two major advances—Adm. Chester Nimitz’s central Pacific offensive and MacArthur’s southern Pacific approach. MacArthur was given overall command of the Leyte operation while Nimitz provided naval support with Adm. William Halsey’s Third Fleet. Preparatory strikes began in early October on the Ryukyu Islands, northern Luzon, and Formosa. After the battlefield was prepped, more than 130,000 troops from the Sixth Army stormed ashore on the first day of the invasion. The landings were mostly uncontested in the early phases of the operation due to the Japanese opting to mount their defense farther inland out of range of naval gunfire. In order to counter the U.S. Navy’s amphibious forces, the Imperial Japanese Combined Fleet initiated Sho-Go (Operation Victory). The operation’s goal was to decoy the U.S. Third Fleet north away from the strategic San Bernardino Strait while converging three task forces to attack U.S. landing forces off of Leyte.

Initially, Darter and Dace shadowed the Japanese armada, reporting back to the Pacific Fleet their speed, heading, and composition. When dawn finally broke on Oct. 23, the submarines made their first visual contact and launched torpedoes. Darter was run aground and eventually destroyed by Japanese aircraft, but not before the crew was safely transferred to Dace.

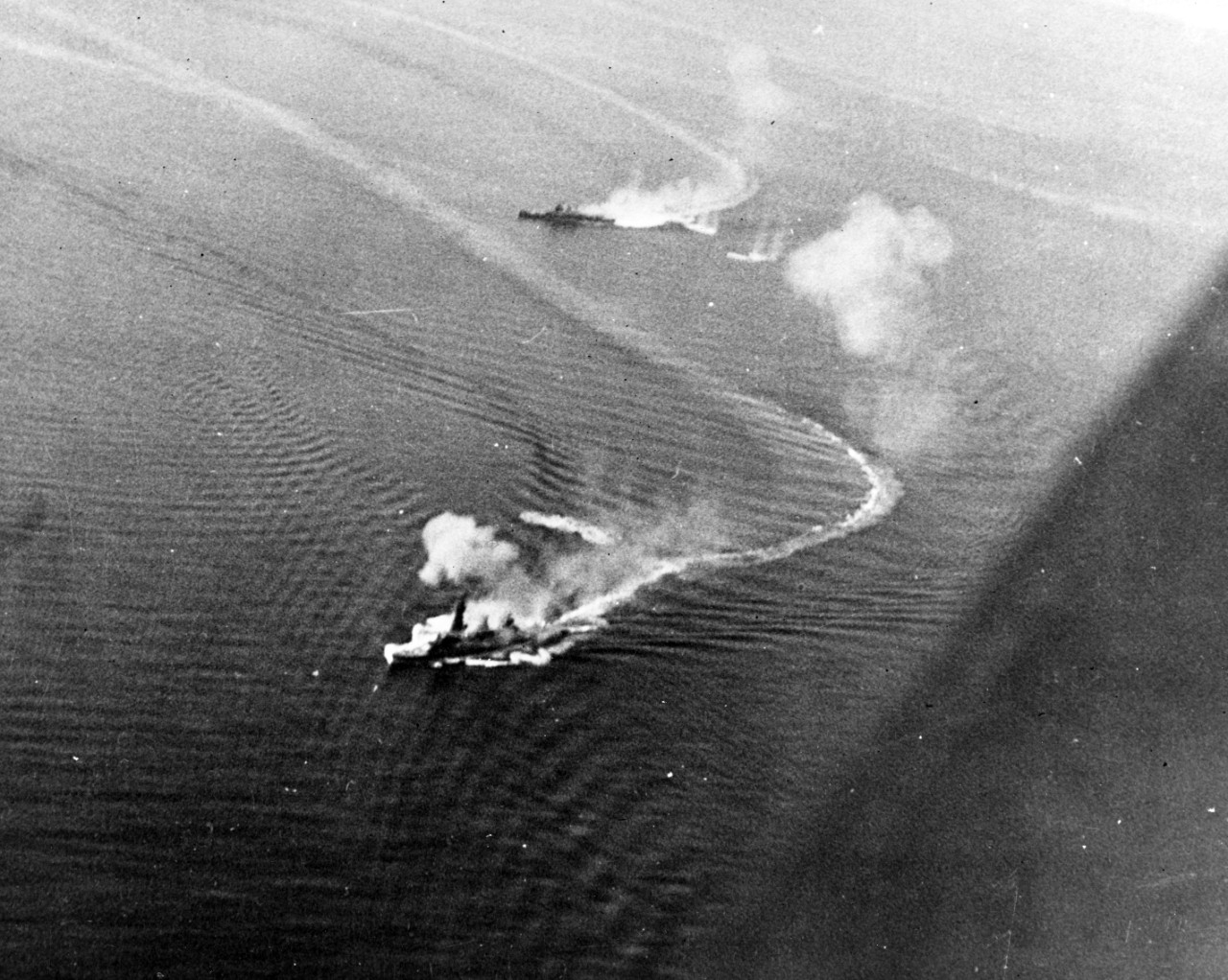

The following day, aircraft from Third Fleet located and attacked the Japanese central force in the Sibuyan Sea and the southern force in the Sulu Sea. In the Sibuyan Sea, several Japanese vessels were damaged and battleship Musashi was sunk. Early in the fight, aircraft carrier USS Princeton (CV-23) was struck by a 550-pound bomb from an enemy dive-bomber that ignited fires on multiple decks. Allied destroyers and cruisers descended on the stricken ship in an attempt to save the crew and the carrier. Rescue and repair efforts continued throughout the day. Just before 3:30 p.m., a massive explosion ripped through the crippled carrier, killing hundreds on the ship as well as crewmembers on cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-62) that were preparing Princeton for tow. Eventually, Princeton was scuttled by torpedoes from USS Reno (CL-96). Meanwhile, after being battered by U.S. submarines and aircraft, a portion of the Japanese force appeared to be retiring to the west, but surprisingly changed course and headed straight toward Leyte.

In the early hours of Oct. 25, the Japanese force in Surigao Strait was essentially annihilated in a night battle with battleships and destroyers from Seventh Fleet and the Royal Australian Navy. As the crippled enemy force attempted to steam north through the narrow strait, PT boats and destroyers relentlessly torpedoed the Japanese vessels. Battleship Fuso and destroyers Asagumo, Michishio, and Yamagumo were sunk.

Despite their losses, the Japanese pressed forward. At the eastern end of the strait, USS California (BB-44), USS Maryland (BB-46), USS Mississippi (BB-41), USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), USS Tennessee (BB-43), and USS West Virginia (BB-48) were lined up as a trap. With the exception of Mississippi, each of the battleships had been damaged during the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack and subsequently returned to service. As a portion of the enemy force approached, American battleships and Australian cruisers delivered full broadsides. Battleship Yamashiro was sunk and cruiser Mogami was seriously damaged. The remaining Japanese force reversed course and withdrew. The battle at Surigao Strait was one of the few naval battles in the Pacific in which aircraft did not play a significant role.

Meanwhile, another Japanese task force, having passed through the San Bernardino Strait, steamed southward along the coast of Samar. Admiral Halsey, who mistakenly shifted his Third Fleet to the north in pursuit of the Japanese decoy force, left the amphibious forces off Leyte essentially unprotected. With the bulk of U.S. Seventh Fleet engaged at Surigao Strait, all that stood between the landing beaches and the Japanese task force were the ships of Task Unit 77.4.3 (radio call sign “Taffy 3”). Although the Japanese had suffered significant losses throughout the battle, the task force approaching Taffy 3 was formidable. Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita’s force included his flagship Yamato, eight cruisers, and nearly a dozen destroyers. Taffy 3 had just six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. Besides being clearly outmatched, the three U.S. destroyers, led by USS Johnston (DD-557), launched aggressive torpedo attacks that damaged heavy cruiser Kumano and caused Yamato to take evasive maneuvers that temporarily took the ship out of the battle. Although Taffy 3’s aircraft were armed for close air support of landing forces, they dominated the airspace above the Japanese force. Task Unit 77.4.2 (Taffy 2), which was a short distance away, eventually joined the fight. Three Japanese cruisers, Chikuma, Chōkai, and Suzuya, were sunk; a fourth, Kumano, was heavily damaged. Shortly afterward, Kurita opted to retreat. In what would become one of the most unlikely victories of the Pacific War, Taffy 3 lost two destroyers, Johnston and USS Hoel (DD-533), and destroyer escort USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413). In addition, escort carrier USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) was sunk by naval gunfire, and escort carrier USS St. Lo (CVE-63) was struck and sunk by one of the first Japanese kamikaze attacks. Taffy 3 was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for the Battle off Samar. Johnston’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

In all, the Japanese attempt to repel the Allied landings on Leyte failed. Japan’s total losses during the Battle of Leyte Gulf amounted to three battleships, one large carrier, three light carriers, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and 11 destroyers. For the Americans, despite tough battles ahead, the offensive in the Philippines and beyond would relentlessly continue. Most important, the conquest of Leyte completely destroyed the strategic threat posed by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Beirut Terrorist Attacks—40 Years Ago

In the early morning of Oct. 23, 1983, during the Lebanese civil war, two truck bombs struck separate buildings housing U.S. Marines and French peacekeeping forces at Lebanon’s Beirut International Airport, killing nearly 300 American and French service members. The first suicide attack carried an explosive force of more than 12,000 pounds of TNT. The truck rammed through the gate at the entrance of the barracks of 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, where the driver detonated the improvised bomb, killing 220 U.S. Marines, 18 Sailors, and three Soldiers. More than 100 were injured in the attack. Minutes later, another suicide bomber struck the Drakkar barracks just a few kilometers away, killing more than 50 French paratroopers. It was the single deadliest day in U.S. Marine Corps history since World War II’s Iwo Jima battle, and the single worst French military loss since the Algerian War (1954–62).

In the aftermath of the attacks, all available French and American military personnel along with the Red Cross rushed to help despite sporadic sniper fire. After dark, an Air Force C-9 medical evacuation aircraft landed at the airport and flew off with the first group of wounded Marines. A British Royal Air Force C-130 transport also arrived that evening, and the next day left for Cyprus with another group of 20 severely injured Marines. Despite continued sniper fire, Air Force C-9s and C-141s also landed at the airport, loaded more wounded, and flew to hospitals in Cyprus, Italy, and Germany.

On Nov. 7, Marine Brig. Gen. Jim R. Joy arrived in Beirut to take command of all Marine Corps operations in Lebanon. The next day, the Marines who had been protecting the Lebanese Science University were pulled back to the airport. Beginning on Nov. 17, Joy ordered the construction of additional bunkers and improvements of existing defensive positions that would help prevent another suicide attack. USS New Jersey (BB-62) had been on station in the waters off Beirut since Sept. 25, but had not fired the ship’s 16-inch or 5-inch guns. However, if the tenuous cease-fire were to break down and the Marines ashore were again targets of rockets, mortars, and artillery, the battleship’s crew was prepared for action. Unfortunately, simply lobbing 16-inch shells into Lebanon would not be much help to the Marines, and a bombardment not carefully directed by spotters on the ground or in the air might kill and injure a number of civilians. On Dec. 4, however, artillery firing from an area dominated by Syrian forces killed eight Marines at the airport and injured two others. It was clear that there was no longer a supposed cease-fire, and President Ronald Reagan authorized retaliatory attacks.

That day, 28 aircraft launched from USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) and USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67), struck targets in the Bekaa Valley east of Beirut. During the engagement, two A-6 attack planes were shot down by intense ground fire. One A-6 pilot, Lt. Mark Lange, was killed and his bombardier-navigator, Lt. Robert Goodman, was taken prisoner (he was released 30 days later with talks facilitated by Rev. Jesse Jackson). After the attack was complete, aerial photos revealed that the strike had been successful. In the days following, reconnaissance flights were conducted without incident.

In the first two months of 1984, the situation in the country had severely deteriorated. The Lebanese army was plagued by defections and desertions, and consistent heavy fighting had further reduced its capabilities. By Feb. 7, Beirut had been lost to Muslim and non-Muslim militias. At this point, the Marine presence could no longer contribute to the hoped-for national reconciliation. Accordingly, President Reagan ordered the Marines to withdraw to Sixth Fleet ships offshore. By Feb. 23, the Marines began movement to rejoin their supporting ships, ending 17 months of continuous operations in the country.

Dwight D. Eisenhower Commissioned

On Oct. 18, 1977, USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) was commissioned at Norfolk, Virginia. “Ike,” named after the nation’s 34th president, was the third nuclear-powered and second Nimitz-class aircraft carrier. The ship’s sponsor was Mamie D. Eisenhower, widow of the late president. Two days later, Cmdr. Gary F. Wheatley, Commander Carrier Air Wing 1, accomplished the first jet landing on board in an LTV A-7E Corsair II. From Jan. 16–July 13, 1979, Dwight D. Eisenhower was underway on its maiden voyage. Heavy seas pounded the ship as it crossed the Atlantic. It relieved USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-67) at Rota, Spain, subsequently passing through the Strait of Gibraltar during the early morning hours of Jan. 30 and into the Mediterranean for the first time. Two Algerian MiGs shadowed Dwight D. Eisenhower on that date, but a pair of Tomcats from the ship intercepted them and they subsequently returned to their airfield. Through most of the deployment, USS South Carolina (DLGN-37) and USS Virginia (CGN-38) steamed with the carrier. The carrier also participated in multiple exercises before returning to the United States.

After providing support for the Iran hostage crisis operations in 1979–81 and peacekeeping forces in the Lebanon civil war in 1982–83, Dwight D. Eisenhower conducted several multinational exercises in the Mediterranean. In October 1985, after its fourth deployment, Ike returned to Newport News Shipbuilding for a complex overhaul. The 18-month shipyard period included the addition of a Close-in Weapons System, NATO Sea Sparrow Missile System, Navy Tactical Data System, Anti-Submarine Warfare Module, and communications upgrades. Ike rejoined the fleet in April 1987. In 1990, Ike completed its sixth Mediterranean deployment, coinciding with a worldwide Dwight D. Eisenhower Centennial celebrating the late president’s 100th birthday. During the anniversary ceremonies off the coast of Normandy, Eisenhower’s son, John, and D-Day veterans embarked on the ship while Carrier Air Wing 7 conducted a memorial flyover of the American cemetery at Omaha Beach. Also during that year, in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, Ike became the second nuclear-powered aircraft carrier to transit the Suez Canal and the first carrier to conduct sustained operations in the Red Sea. Ike served as a ready striking force in the event Iraq invaded Saudi Arabia, and participated in maritime interception operations in support of a United Nations embargo against Iraq. After a subsequent extensive shipyard and training period, Ike deployed in September 1991 to the Arabian Gulf to continue multi-national operations in support of Operation Desert Storm. Ike returned to Norfolk in April 1992 and entered the Norfolk Naval Shipyard for overhaul in January 1993. Ike returned to the fleet on Nov. 12, 1993.

In September 1994, Ike and the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division made history with the concept of “adaptive force packaging.” The division’s soldiers and equipment were loaded on board, and the Ike Army/Navy team headed for Port-au-Prince to spearhead Operation Uphold Democracy, the U.S.-led effort to restore the democratically elected government of Haiti. One month later, Ike departed for a six-month deployment, which included flying missions in support of Operations Southern Watch and Deny Flight. This period marked the first time that women deployed as crewmembers of a U.S. Navy combatant ship: Ike’s crew included more than 400 female personnel.

In February 2000, Ike departed Norfolk for a millennium cruise to the Mediterranean Sea and Arabian Gulf. During that deployment, the air wing performed the ship’s first combat ordnance delivery while operating in support of Operation Southern Watch in Iraq. In May 2001, Ike began its mid-life, comprehensive refueling complex overhaul in the shipyard at Newport News, returning to Naval Station Norfolk in January 2005. On Oct. 3, 2006, Ike deployed for seven months to U.S. Fifth Fleet’s area of operations in support of ground troops in Iraq and Afghanistan and to conduct maritime security operations. In July 2009, Ike completed a six-month deployment to the Mediterranean and Arabian Gulf, returning again in January 2010 for another six-month deployment in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. In September 2010, Ike began a regularly scheduled planned incremental availability at Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, returning to Norfolk in June 2011. In December 2012, Ike completed another six-month deployment in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and returned to its homeport in July 2013.

In June 2016, Dwight D. Eisenhower deployed to U.S. Sixth Fleet’s area of operations. During that deployment, sorties from Ike dropped 1,100 bombs on ISIS targets in Iraq and Syria. The carrier completed the underway in December—its 17th deployment to the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. On June 26, 2020, the ship surpassed USS Theodore Roosevelt’s (CVN-71) record of 160 consecutive days at sea without a port call, which was attributed mostly to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since that time, Dwight D. Eisenhower has participated in a number of exercises and supported Operation Inherent Resolve. Ike is scheduled to be replaced around 2029 by Gerald R. Ford-class carrier USS Enterprise (CVN-80).

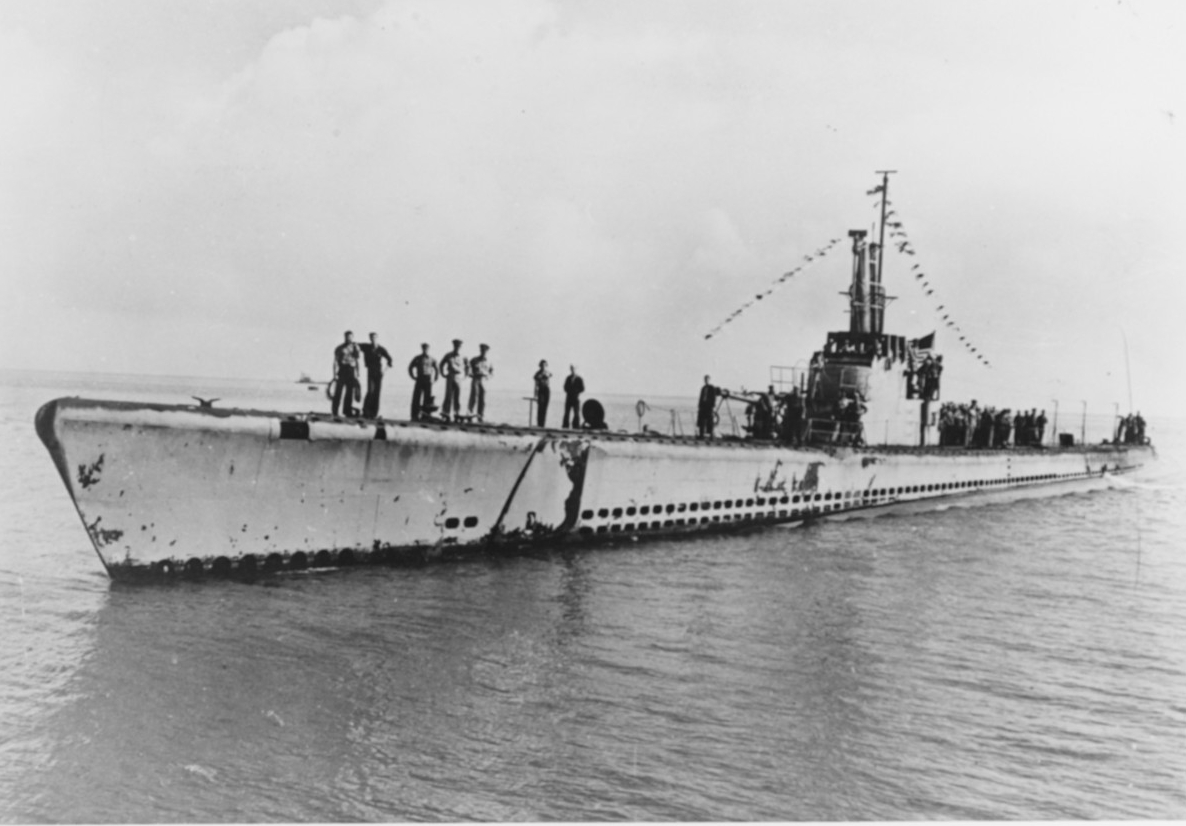

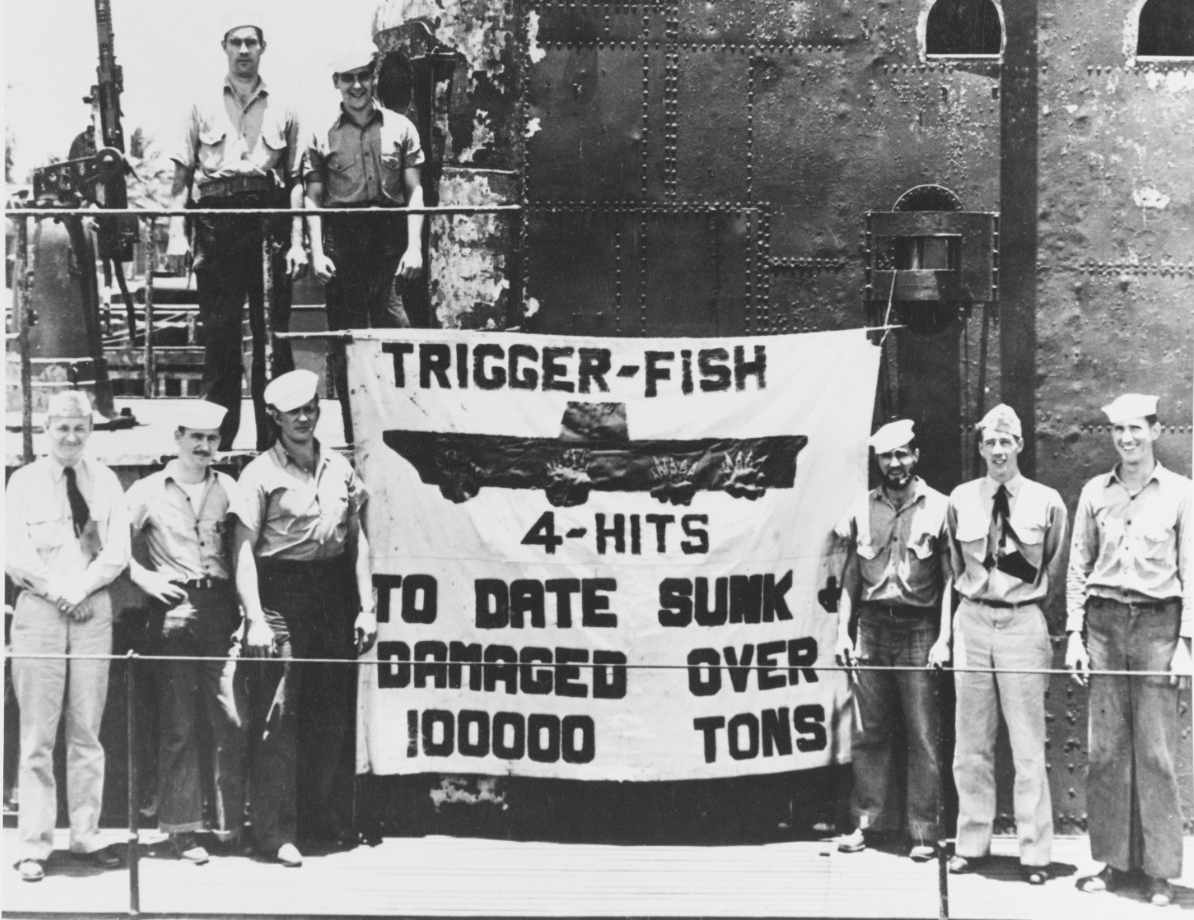

Today in Naval History—Pull the Trigger

Before dawn on the morning of Oct. 17, 1942, near the mouth of Bungo Channel between the Japanese home islands of Kyushu and Shikoku, USS Trigger (SS-237) fired two spreads of torpedoes that sank Japanese freighter Holland Maru. It was the first enemy ship the submarine sank during World War II. Over the course of the war, the submarine sank 27 ships and damaged another 13. During its second patrol, in addition to the sinking of Holland Maru, the boat damaged two large tankers and another freighter. Trigger's third patrol was a mining mission as well as an offensive patrol. It, too, was in Japanese waters. Trigger observed a large freighter blow up and sink when it hit a mine the submarine had laid. It also sank two freighters by torpedo attacks. On Jan. 10, 1943, Trigger torpedoed and sank Japanese destroyer Okikaze near Honshu. Trigger covered the Palau-Wewak (New Guinea) traffic lanes on its fourth patrol and succeeded in sinking one freighter and damaging two more. Again in the area south of Honshu, Trigger, on its fifth patrol, sank a large freighter and damaged an aircraft carrier and a tanker. Trigger’s sixth and seventh patrols were in the East China Sea. On its sixth patrol, it sank three large tankers and a freighter, and also damaged another freighter. Its seventh patrol resulted in the sinking of four good-sized freighters, one tanker, and one large transport. The eighth patrol of Trigger was made in the Caroline Islands on the Truk–Guam route, and it sank a large freighter-transport and an escort vessel. It sank four freighter-transports as well as a patrol vessel near Palau on its ninth patrol and damaged a large tanker, two freighters, and a sampan. Trigger's tenth patrol covered the northern Ryuku Islands (Nansei Shoto) area. It received partial credit for sinking a small tanker, which was sunk cooperatively with USS Salmon (SS-182). Trigger's eleventh patrol was in Japanese waters as well, but resulted in disappointingly few enemy contacts and no attack opportunities. This ship was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its fifth, sixth, and seventh patrols.

On its twelfth and final patrol, Trigger again headed for the Nansei Shoto area. On March 18, 1944, it attacked a convoy west of the islands, sinking the cargo ship Tsukushi Maru No. 3 while damaging another. The attack was reported two days later, and the submarine was subsequently ordered to radio as many movements of the convoy as possible to help find a safe passage through a known Japanese-mined area of the East China Sea. On March 24, Trigger was ordered to begin patrolling west of the islands the next day and to steer clear of restricted areas. On March 26, it was ordered to join a wolf pack called “Earl’s Eliminators” and to acknowledge receipt of the message. A weather report came from the submarine that day, but no confirmation of having received the message in regards to the wolf pack order. The weather report was Trigger's last transmission. On April 4, it was ordered to proceed to Midway, but it had not arrived by May 1 and was reported as presumed lost.

On March 29, according to post-war records, Japanese planes and ships joined in a two-hour attack on a submarine. There were other U.S. submarines in the area. USS Threadfin (SS-410) reported that it heard many depth charges and several heavy explosions east of its position. Trigger was ultimately struck from the Navy list on July 11, 1945. It received 11 battle stars for its World War II service.