Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

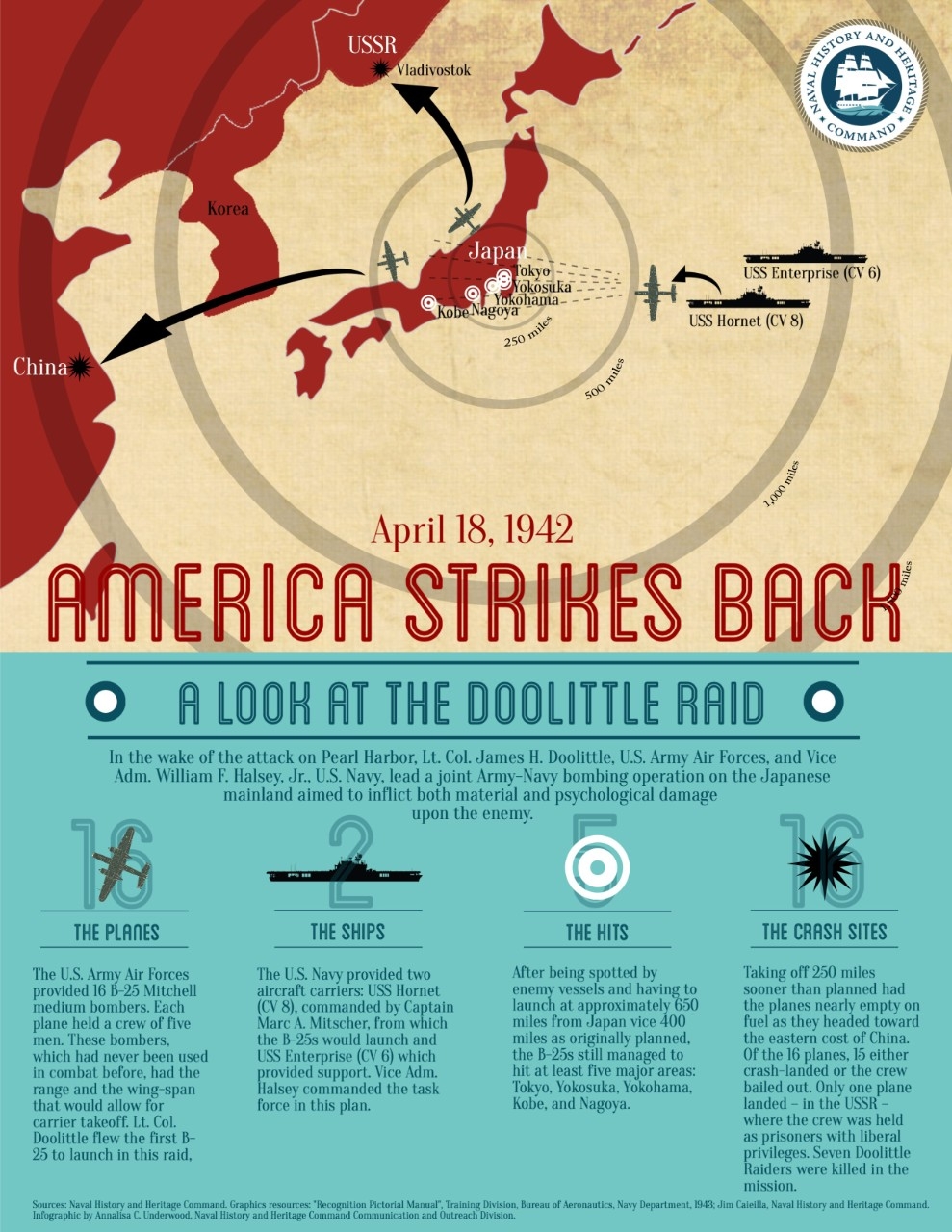

On April 18, 1942, the Doolittle Raid, consisting of 16 Army Air Forces B-25 bombers, launched from the deck of aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) approximately 650 miles off Japan. Conceived in the aftermath of the Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack that brought the United States into World War II, the goal of the raid was to attack Japanese industrial centers in an effort to inflict both “material and psychological” damage on Japan. Planners hoped the attack would provoke the enemy to recall combat operations elsewhere in order to defend its homeland. Originally, the plan called for bombers to be launched from, and recovered by, an aircraft carrier. Research disclosed that the North American B-25 Mitchell was the best-suited aircraft for the mission. Tests off Norfolk, Virginia, soon revealed that while a B-25 could take off with comparative ease, landing on the carrier was next to impossible.

After it was learned the aircraft would be unable to land back on the carrier, planners decided to transport them to a point east of Tokyo. The first plane would drop incendiaries, and the bombers would follow. The aircraft would then proceed to either the east coast of China or to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. However, Joseph Stalin’s unwillingness to provoke Japan compelled the selection of landing sites in China. At a secret conference in San Francisco, Army Air Force Lt. Col. James Doolittle, who was designated to lead the attack, met with Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., who would command the task force that would take Doolittle’s aircraft within range of the Japanese Empire. They agreed the launch point would be somewhere within 600 miles due east from Tokyo; however, if discovered, Task force 16 (TF-16) would launch the planes early.

In preparation for the mission, 24 planes were drawn from the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 17th Bombardment Group. The aircraft had additional fuel tanks installed, and all equipment deemed unnecessary was removed. In early 1942, intensive training began with the all-volunteer crew. The mission was considered extremely dangerous and would require a great amount of skill. Some even considered it a suicide mission. Crews practiced intensive cross-country flying, night flying, and navigation, as well as low-altitude approaches to targets, rapid bombing, and evasive action. Beginning on March 31, 16 B-25s were loaded onto Hornet at Alameda, California, and the ship steamed to rendezvous with aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) to form part of Halsey’s TF-16.

The Japanese were expecting the Americans to approach within 200 miles of Japan as they had done in early naval raids in the Marshalls and Gilberts, and at Wake and at Marcus. In anticipation, the Japanese 26th Air Flotilla launched 29 medium bombers equipped with torpedoes, escorted by 24 carrier fighters equipped to find TF-16. Monitoring U.S. Navy radio traffic, the Japanese deduced that a carrier-led attack on the home islands was a possibility after April 14. On April 18, TF-16 was within 650 miles of Japan when one of the Japanese early-warning picket boats, operating at intervals offshore, discovered the task force and radioed a sighting report. Although Halsey had agreed to take TF-16 closer to Japan, he recognized the potential for mission failure and ordered the 16 B-25s launched.

The deployment of long-range U.S. Army Air Force bombers took the Japanese by surprise. Taking a little over an hour to launch, the B-25s, carrying high-explosive and incendiary bombs, hit targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Kobe, and Nagoya, against little opposition. Bombs from the B-25s damaged aircraft carrier Ryuho at Yokosuka and thus delayed its completion. Of the 16 B-25s, 15 crashed in occupied China, where the Japanese inflicted brutal reprisals against the Chinese populace in the Chekiang province. One B-25 landed intact at Vladivostok, where the Soviets interned it and its crew.

Although the material damage inflicted by Doolittle’s raiders proved minuscule, the effect of the American air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous. Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed unlikely by the Japanese naval general staff, had occurred mostly unobstructed. The Doolittle Raid dissolved the residual doubts harbored within the naval general staff whether or not a thrust against the important U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out the previously unengaged U.S. carriers, should be attempted. The Japanese army, previously reluctant about the operation, went along with the navy’s plan.

Operations Persecution and Reckless

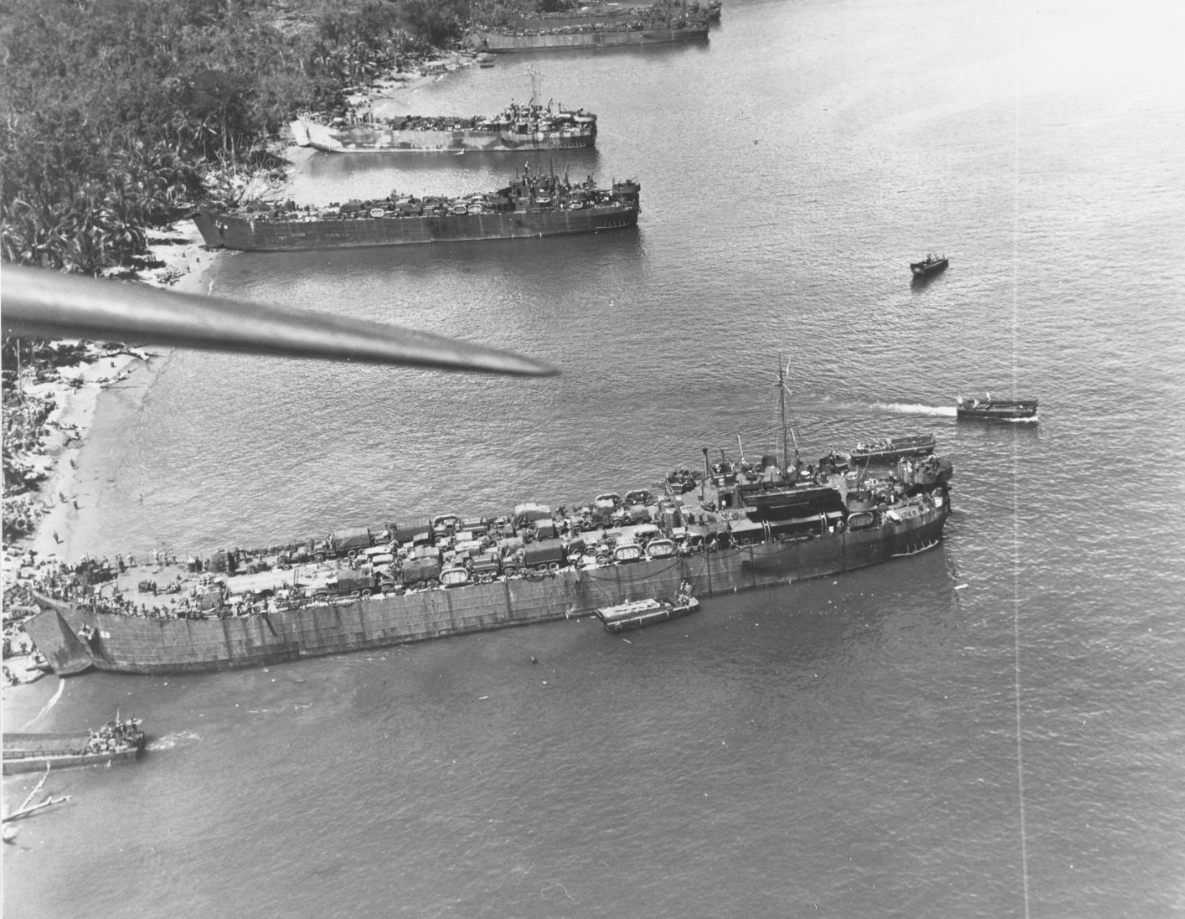

On April 21, 1944, Task Force 58, led by Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, began bombing Japanese airfields and defensive positions at Hollandia, Wakde, Sawar, and Sarmi on New Guinea, in preparation for U.S. Army amphibious landings. The Navy played a crucial role in Operations Reckless and Persecution to take Japanese airfields near the north coast of New Guinea. The operations—Reckless, which was intended to take Hollandia and nearby airfields, and Persecution, focused on landing strips near Aitape—were highly successful in securing New Guinea for further island-hopping operations that ultimately helped the Allies win the war in the Pacific.

The conquest of the valuable New Guinea airfields was necessary to isolate Japanese forces in Wewak and Rabaul. It also led to the control of the 600-mile stretch from Truk to Guam to further launch offensives to the north and to the west. At these airfields, the Allies would be able to get the heavy-bomber bases needed for Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s push to the Philippines and Adm. Chester W. Nimitz’s advancement toward the Marianas and Palau. In early 1944, MacArthur and Adm. William “Bull” Halsey, Jr., worked out plans for what would be Operations Reckless and Persecution.

The spring 1944 fight for northern New Guinea’s airfields was in part a product of the Casablanca Conference (the January 1943 meeting between U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and members of the French government-in-exile). At the conference, they resolved to work together to attack Japan on multiple fronts and to take Japanese bases in New Guinea. This push would be part of a wider effort to weaken the Japanese in three ways: divert their attention to the Southwest Pacific in time for the Allies to strike in the north; eliminate the Japanese Southwest Pacific headquarters at Rabaul; and reconquer the Philippines, under Japanese occupation since 1942.

After the initial first three days of landings, Soldiers were met with only scant resistance with almost all Japanese personnel having fled. In about six weeks, Soldiers were basically conducting mop-up operations, rounding up stragglers. During the operations, 124 Americans were killed, 28 went missing, and another 1,057 were wounded. The Japanese suffered at least 3,300 killed and more than 600 taken as prisoners of war.

After the areas were declared secure, both the Navy and Army, with the help of Allied engineers, began in early June to develop bases in and around Hollandia. Humboldt Bay became a naval advance base with supply and ammunition depots, ship repair and unloading facilities, and other support installations. Tanahmerah Bay housed a new fuel depot. These bases, as well as the airfields around nearby Lake Sentani, soon became an invaluable staging area for the Philippines Campaign of 1944–45.

The Sullivans Commissioned

On April 19, 1997, USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) was commissioned at Staten Island, New York, with Kelly Ann Sullivan, granddaughter of the youngest Sullivan brother Albert, as its sponsor. The Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer is the second U.S. Navy ship named after the five Sullivan brothers who were tragically killed in action when USS Juneau (CL-52) was sunk on Nov. 13, 1942, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The first ship named after the brothers was USS The Sullivans (DD-537). It was commissioned in 1943, and its sponsor was the brothers’ mother, Alleta. It received nine battle stars for its World War II service and earned two more during the Korean War. It also conducted blockade services during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The ship was decommissioned in 1965 and is currently a memorial at the Buffalo and Erie County Naval and Military Park in New York. The current destroyer named for the brothers is homeported in Mayport, Florida. Its motto is “We Stick Together,” a phrase thought to have been spoken by the brothers when asked to separate during the war. In February 2002, The Sullivans deployed with the John F. Kennedy Battle Group in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

The Sullivan brothers from Waterloo, Iowa, initially served in the Atlantic, but were transferred to the Pacific in August 1942. Late in October 1942, Juneau took part in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and in November fought off Guadalcanal. During that battle, a torpedo strike severely damaged the ship. The following morning, the crippled cruiser, down by the bow and struggling to gain speed, departed the battle area. Handling sluggishly as it limped through the calm sea, Juneau was an easy target for nearby Japanese submarine I-26. A torpedo strike hit the damaged cruiser and detonated its magazines. The resulting explosion tore it apart, and the ship slipped below the waves in just 42 seconds. Four of the Sullivan brothers, Coxswain Francis Sullivan and Seamen 2nd Class Joseph, Madison, and Abel, failed to make it topside in time to abandon ship. Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class George Sullivan, wounded during the attack, managed to get over the side of the ship and pulled himself onto a raft, but he died of his wounds a few hours later. Only 10 of approximately 140 crewmembers were rescued from Juneau. The death of the brothers was the biggest blow to any one family in U.S. wartime history.

George and Francis Sullivan—the two eldest—enlisted in the U.S. Navy on May 11, 1937, and served on the destroyer USS Hovey (DD-208) until June 1941. At Des Moines, Iowa, on Jan. 3, 1942, George and Francis, accompanied by their younger brothers Joseph, Madison, and Albert, reenlisted to avenge the loss of Seaman 1st Class William V. Ball, a friend who was killed while serving on the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. After receiving initial training at the Naval Training School in Great Lakes, Illinois, all five brothers, at their expressed request, joined light cruiser Juneau at the New York Navy Yard on Feb. 3, 1942.

The brothers were survived by their parents, their only sister Genevieve, and the youngest brother's wife and son, Katherine Sullivan and Jimmy.

U.S. Marines’ First Battle on Foreign Soil

After marching more than 500 miles from Egypt, U.S. Navy agent William Eaton led a small force of U.S. Marines and mercenaries against the Tripolitan port city of Derna. The contingency was on a mission to depose Yusuf Karamanli, the ruling pasha of Tripoli, who had seized power from his brother, Hamet Karamanli, a pasha who was sympathetic to the United States.

On April 27, 1805, a major American victory came during the Battle of Derna, which was the U.S. Marines’ first battle and the first time a U.S. flag was raised on foreign soil. Supported by the heavy guns of schooner Nautilus, brig Argus, and sloop-of-war Hornet, Marines and Arab mercenaries captured the city in North Africa and deposed Yusuf Karamanli. Lt. Presley O’Bannon, commanding the Marines, performed so heroically in the battle that Hamet Karamanli presented him with an elaborately designed sword that now serves as the pattern for the swords carried by U.S. Marine officers. The battle is notably recalled in the first verse of the Marines' Hymn: “From the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli, we fight our country's battles in the air, on land, and sea.”

During the 17th and 18th centuries, state-sanctioned pirates from the Barbary States (Morocco, Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers) would seize unprotected merchant ships off the coast of northern Africa and demand ransoms from the crews’ families and governments. The general practice at the time was to simply pay “tributes” to the pirates for safe passage in the Mediterranean instead of confronting them militarily. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 that formally ended the American Revolution, the United States hoped it would enter a new era of global free trade. However, without the protection of the powerful British Royal Navy, American merchants quickly found themselves defenseless against Barbary pirates. At the time, the high seas were the most economically viable way to transport goods, and the Mediterranean was vital to American prosperity. Presidents George Washington and John Adams chose to pay tributes to the Barbary pirates, but the bribes failed to ensure full protection and were subject to the whims of the Bashaw of Tripoli, the Bey of Tunis, the Sultan of Morocco, and the Dey of Algiers. With ransom prices escalating, newly elected President Thomas Jefferson sent America’s reestablished Navy to confront the Barbary powers.

In the first Barbary War, the leader of Tripoli gave the U.S. an ultimatum—increase tribute to $225,000 or go to war. After years of rising ransom prices and never-ending negotiations for captured ships and crews, President Jefferson decided to use force to ensure American safety in the Mediterranean. Jefferson, as Secretary of State, had long taken a hard line against Barbary piracy. In May 1801, he ordered a squadron, led by Commodore Richard Dale, to blockade Tripoli and to attack any interfering Barbary ship. Lt. Andrew Sterrett, commander of the schooner Enterprise, won the first American victory of the conflict when, on Aug. 1, 1801, he defeated 14-gun corsair Tripoli after a fierce but one-sided battle. Enterprise did not suffer a single casualty during the engagement, but because Congress had not formally declared war, Sterrett was unable to take the ship as a prize. Instead, he ordered the battered pirate ship into port, and his crew threw all the enemy ships’ guns overboard. The next victory for Enterprise came on Jan. 17, 1803 when, after spending months of carrying dispatches, convoying merchantmen, and patrolling, it defeated Paulina, a Tunisian ship under the charter of the Bashaw of Tripoli. On May 22, it ran a 30-ton craft ashore, and for the next month, Enterprise and other ships of the Mediterranean Squadron cruised inshore bombarding the coast and sending landing parties to destroy enemy small craft. Later that year, Enterprise joined the frigate Constitution to capture Tripolitan ketch Mastico. Refitted and renamed Intrepid, the ketch was given to Enterprise's commanding officer, Lt. Stephen Decatur, Jr., for use in an expedition to burn frigate Philadelphia, which was captured by the Tripolitans and anchored in the harbor of Tripoli. Decatur and his crew carried out the daring mission perfectly, destroying the frigate and depriving Tripoli of the opportunity to convert it to a Barbary warship.

In August 1804, Decatur, under the overall command of Mediterranean commander Commodore Edward Preble, led another attack on Tripoli Harbor, during which he boarded enemy gunboats and rescued several American prisoners. During the bloody battles, Decatur’s brother James was killed, but a wounded sailor, Reuben James, saved his life by inserting himself between his leader and a Barbary sword. The first Barbary War ended when an agreement between General Consul Tobias Lear and Danish Consul Nicholas Nissen stipulated that after paying a $60,000 ransom, the United States no longer needed to pay tributes to Tripoli. Americans celebrated the treaty as a victory for free trade. Hamet returned to exile in Egypt, Eaton returned to America, and the war with Tripoli came to an end.