Juneau I (CL-52)

1942

The capital city of the territory of Alaska.

I

(CL-52: displacement 6,000; length 541'6"; beam 53'2"; draft 16'4"; speed 32 knots; complement 623; armament 16 5-inch, 16 1.1-inch, 8 20 millimeter, 6 depth charge projectors, 2 depth charge tracks; class Atlanta)

The first Juneau (CL-52) was laid down on 27 May 1940 at Kearny, N.J., by the Federal Shipbuilding Co; launched on 25 October 1941; and sponsored by Mrs. Harry I. Lucas, wife of the Mayor of the City of Juneau.

Commissioned at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 14 February 1942, Capt. Lyman K. Swenson in command, Juneau fit out at her delivery yard, departing New York on 22 March 1942, and proceeded to nearby Gravesend Bay. She arrived in her designated training area at 0800, took on ammunition and then conducted exercises in those waters through the 24th. Underway at 0748 on 25 March, Juneau participated in exercises near Staten Island and anchored for the night off Tompkinsville. She continued to drill in the vicinity through the 27th.

At 0000, on 28 March 1942, Juneau reported for duty with Commander Task Group (TG) 27.1 in response to a potential submarine menace. She passed the Delaware capes at 1700, and anchored north of the Harbor of Refuge overnight. Juneau got underway by 0730 the next morning, and while steaming in heavy seas made radar contact with an unknown object 780 yards distant. While she employed three embarrassing barrages that yielded unknown results, the concussion of the depth charges opened circuit breakers on the forward distribution board resulting in a temporary loss of steering control and gyros. Despite such issues the new cruiser arrived in the Chesapeake Bay at 1530 without further incident. Over the course of the next week Juneau participated in multiple training drills.

While at anchor off Naval Operating Base (NOB) Hampton Roads [Naval Station Norfolk], Va., on 4 April 1942, Capt. Swenson conducted a material inspection of the ship. On 6 April, Juneau was underway for gunnery training in the vicinity of the San Marcos shipwreck in the Chesapeake. She conducted exercises in the area for several days and at night anchored near the San Marcos wreck–the shattered remains of the old battleship Texas that had served as a target for many years. In the early morning hours of 9 April, she departed the area post haste to answer a distress call from the merchantman Middlesex. She shortly thereafter arrived in the area near Smith Point Lighthouse along with the gunboat Paducah (PG-18), and located Middlesex. Swenson sent a boarding party to Middlesex in order to obtain further details of the incident, and learned that Middlesex collided with the Argentinian freighter Brazil; and as a result Middlesex incurred a hole on her starboard bow, while Brazil had sunk before Juneau’s arrival. Fortunately for Middlesex the hole in her bow was above the water line and she was in no immediate danger. Juneau’s ship log indicated that the wreck of Brazil lay 3,320 yards off of Smith Point Lighthouse and was not visible above the water. Following Middlesex’s departure, Juneau remained in the vicinity and anchored for the night.

After intermittent mist and fog prevented Juneau from conducting anti-aircraft drills early on 10 April 1942, she stood out to rendezvous with the small seaplane tender Matagorda (AVP-22) to transfer a photography party bound for Norfolk. She then spent the remainder of the day engaging in training drills and eventually anchored for the night near the entrance to the Severn River Channel. On 11 April, she made her way to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., and anchored there for several days. Beginning at 0600 on 13 April, Juneau began a week of exercises and inspections while remaining in the Chesapeake Bay area.

Observers from the Department of the Navy watched Juneau conduct experimental drone 5-inch firing tests on 22 April 1942; the tests resulted in no damage to the drone. The day became more eventful when at 1123, a J2F-5 (BuNo 0061) Duck amphibian piloted by Lt. Jesse B. Burks and carrying Cmdr. Percival E. McDowell and AMM1c S. L. Morel, nosed over while landing, a half mile off the starboard quarter. Juneau’s crew successfully recovered the men, none of whom were injured. The plane was towed to the side of the ship and hoisted out of the water by the cruiser’s boat crane. After she transferred the plane the cruiser anchored for the night near the entrance to the Thimble Shoal Channel. The next day she headed back to the Chesapeake Bay to continue training and exercises.

In the late morning of 25 April 1942, Juneau got underway from the Chesapeake Bay. While steaming in low visibility she experienced a sudden shock from two underwater explosions, similar to depth charges, and heard one round of gunfire to the northeast. Poor visibility prevented any fruitful observations and Swenson shaped a course for Hydrographer Canyon off of George’s Bank, southeast of New England. On 26 April, Juneau picked up an enemy submarine’s radio signal 15 miles to the west. There were no further developments and by 1550 she had arrived at her designated area and anchored. Over the next several days Juneau conducted exercises with the battleship North Carolina (BB-55) and submarine S-20 (SS-125).

On 2 May 1942, the cruiser sailed for New York via the Cape Cod Canal. She put into Base George [Newport, R.I.] for a brief visit, dropping anchor at 1645, off of Gull Rock. During her stop there, Vice Adm. Royal E. Ingersoll made an informal visit to the ship. By 1740, Juneau again stood down the channel, bearing toward N.Y. During her voyage she noticed a merchant vessel aground on Valiant Rock with two tugs standing by; and as her services were not needed, she anchored for the night at Hempstead Harbor. Delayed by a thick fog the next day, Juneau proceeded through Hell Gate at 1700, and anchored in Gravesend Bay. At 1854, she unloaded 300 tons of ammunition and had some welding repairs completed—during the sojourn some of the crew were granted shore leave.

At 1430 on 4 May 1942, Juneau received word that she was to proceed to San Juan, P. R. Swenson recalled the crew from shore leave and the ship made preparations to clear Gravesend Bay. The cruiser weighed anchor at 1247 the next day, and set a course for San Juan. While en route on 6 May, Juneau’s crew sighted a life raft at 33°34'N, 71°03'W, bearing the partial inscription “Goteb…” but the raft was empty. On 7 May, Juneau steamed on at maximum speed and arrived in San Juan at 1626, where she moored to the east side of Pier 1 and refueled.

Shortly after her arrival in San Juan, Juneau was called upon to assist with Allied efforts to prevent military assets of the Vichy French government from falling into German hands. The Vichy French ships in question included the aircraft carrier Béarn, and the light cruisers Jeanne d'Arc, and Émile Bertin. At 0010 on 8 May 1942, Swenson received verbal orders from higher headquarters to steam to the vicinity of Fort-de-France and Pointe-à-Pierre in order to prevent the escape of French men-of-war in the area. While en route, at 1908, the cruiser made underwater sound contact with an object bearing 2,000 yards distant and initiated a depth charge attack releasing three 600-pound depth charges and six 300-pound depth charges. It was later determined that no submarine was present and Juneau arrived in her patrol area later that day.

While patrolling off the Martinique-Guadeloupe area on 9 May 1942, Juneau sighted and closed in on a merchant vessel at 15°41'N, 58°13'W. The vessel responded correctly to Juneau’s challenge and was identified as the U.S. freighter Nishmaha. The next day, Juneau sighted another merchant vessel at 0630, and proceeded to investigate her, but was unable to identify the vessel from the call hoisted in response to her challenge. Consequently, Swenson sent a boarding party to investigate, and found her to be the Belgian cargo steamer Elisabeth van België. After allowing the merchant ship to proceed, Juneau proceeded to rendezvous with Task Unit 26.3.9, which consisted of the light cruisers Savannah (CL-42) and Cincinnati (CL-6).

Juneau received word on 11 May 1942 that Vichy French ships might attempt to escape in the afternoon. No flight attempt ultimately transpired on the 11th, but the next day, while patrolling eastward of Martinique-Guadeloupe, Juneau received a warning that Émile Bertin and Jeanne d’Arc would attempt to escape. News reports during that time indicated that the Vichy French government considered U.S. demands to establish military garrisons in the French West Indies, as well as the demilitarization of French warships, to be Acts of War. Still nothing transpired and Juneau stood her station.

On 14 May 1942, Juneau received notification that an arrangement had been reached, which guaranteed that the Vichy French ships would not move. At 2000, Juneau was released from her duties in the area and steamed independently back to San Juan. The next day, Juneau was rerouted to St. Thomas to fuel; she arrived there on 16 May and moored at the oil dock. During the stop, Vice Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, Commander, Task Force (TF) 23, came on board and breakfasted with Capt. Swenson. At 0930, Juneau weighed anchor and set out to participate in exercises in the area. Juneau rendezvoused with Cincinnati north of the San Juan Harbor on 17 May; and shortly thereafter she began steaming, in company with the older warship back to N.Y. On 20 May, Juneau arrived in New York amid a thick fog at 0530, and anchored in Gravesend Bay. On 21 May, she shifted to the New York Navy Yard where she moored and commenced an overhaul, ending her shakedown cruise.

After more than a week at port, Juneau departed the Navy Yard on 1 June 1942, and set a course for Naval Base Bayonne, N.J. After calibrating her degaussing gear, she returned to Gravesend Bay to take on ammunition at Fort Lafayette. She finally completed loading on the 3rd and was underway for Base George by the early morning hours of the 4th. On the 7th she departed Base George for Base Queen and while at anchor civilian engineers came on board and installed FD Radar amplifiers. On 9 June, she was en route to Base Roger. Juneau remained at Base Roger until 20 June, undergoing inspections and conducting exercises. On the 15th she was repainted a new camouflage consisting of alternating irregular patters of haze gray and off white. She stood out of Base Roger at 2350, on 20 June, and shaped a course for Base George to join TF 22. While en route she took up a station 800 yards astern of the aircraft carrier Ranger (CV-4). She arrived at Base George in Narragansett Bay, R.I., amid heavy fog on 22 June, and took on fuel and supplies.

Juneau made a brief return to the Boston Navy Yard on 24 June 1942; but by 1 July, Juneau and the rest of TF 22 were underway headed to Base Dog. The TF consisted of: Ranger, heavy cruiser Augusta (CA-31), Ellyson (DD-454), Forrest (DD-461), Fitch (DD-462), Corry (DD-463) and Hobson (DD-464). They arrived at Base Dog on 7 July. Juneau conducted several exercises in the area including a few with USAAF planes on 10 July. At 1953 on 12 July, a consolidated PBY-5A Catalina flying boat (BuNo 2399) from Scouting Squadron (VP) 31, piloted by Lt. Cmdr. William W. Winika crashed while attempting to land at too high an airspeed. After arriving on the scene Juneau sent out a whaleboat, and although two badly injured crewmen were rescued the pilot and nine other crewmen perished in the crash. Among the lost crewmen was the former baseball star Lt. Joseph S. Boren, who had been signed by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1935. The plane itself was also lost to the sea and no other bodies were removed from the wreckage at that time. Following the incident Juneau continued conducting exercises in the area. On 16 July, at 1900, she was dispatched as part of Commanders TG 23.3, along with Omaha (CL-4) and Somers (DD-381) to intercept and reinforce convoy AS-4, which had been attacked northeast of the Bahamas earlier that day by U-161 (Korvettenkapitän Albrecht Achilles in command). While en route on 17 July, she made sound contact and released depth charges, but ascertained no evidence of an enemy submarine.

Amid calm seas at 1001 on 18 July 1942, Juneau and her task group sighted convoy AS-4 in the vicinity of 19°09'N, 60°13'W. The convoy escorts consisted of Livermore (DD-429), Wilkes (DD-441), Gleaves (DD-423) and Mayo (DD-422). Upon joining the convoy, Juneau assumed position in the screen. On 20 July, while enjoying smooth seas, Juneau picked up multiple contacts throughout the day on radar, convincing Swenson that “enemy submarines were in the vicinity of the formation.” On 25 July, Juneau crossed the equator and a “crossing the line” ceremony took place with the ship’s log recording that all “pollywogs were dealt with accordingly.” On 28 July, after ten days escorting convoy AS-4, Juneau made landfall at Olinda Point Lighthouse near Pernambuco, Brazil; entering the harbor in clear weather, light seas, and bright moonlight. She moored in berth No. 8.

Shore leave and liberty expired at 1830 on 29 July 1942, and Juneau sailed the next day escorting the convoy on its return journey. She remained in company until 5 August, when they were joined by British convoy WS-21P at 9°00'S, 1°26'W; the convoy included the liner Empress of Japan, the light cruiser HMS Orion (85) and three other British destroyers. Juneau and Somers were relieved of their part in the escort, and continued on toward the Cape Verde Islands to conduct exercises and sweeps of the area. On 12 August, Juneau and Somers were dispatched to St. Paul’s Rocks [Saint Paul Archipelago] to look for evidence of enemy forces. Soundings in the area did not indicate any enemy activity and the two ships then steamed on towards Fernando de Noronha, Brazil.

On 14 August, Juneau set out on her own to return to Base Dog. While en route the next day, Juneau rerouted to avoid a known enemy submarine on patrol in the area ahead of her. She steamed on at high speed to clear the area quickly and on 17 August, the cruiser arrived safely at Tobago Island where she berthed at Pier 1. Eight hours after her arrival Juneau got underway for Cristóbal, C.Z.

In the late evening of 19 August 1942, Juneau arrived at the Canal Zone, and she transited the isthmian waterway in just under six hours. She moored to Pier 8, Balboa and took on provisions. On 21 August, the cruiser entered dry dock to repair a leaky fuel oil tank, as well as, to be repainted for operations in the Pacific. On 22 August, she departed Balboa and shaped a course for Tongatabu, Tonga Islands, to join South Dakota (BB-57), Duncan (DD-485), Lardner (DD-487) and Lansdowne (DD-486) at sea. Other than the occasional “chilly and uncomfortable day,” the journey proved largely uneventful. Juneau sighted South Dakota at 11°02'S, 137°37'W.

By 0530, on 30 August 1942, Juneau was on station, and in company with TG 2.9, Rear Adm. Willis L. Lee wearing his flag in South Dakota. On 31 August, Juneau fueled from the battleship, receiving, in addition, some “ice cream, various papers, and movies.” Shortly thereafter the group continued on its way to Tongatabu. The task group arrived at Tongatabu at 1158, on 4 September, and Juneau moored to the port side of the tanker W.S. Rheem. Juneau remained at anchor at Tongatabu, for several days, until, on 7 September, she received orders to rendezvous with TF 18. She set out that same day in company with Lansdowne, Duncan, Lardner, and Laffey (DD-459).

Juneau joined TF 18 on 10 September 1942. The task force was commanded by Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes in the aircraft carrier Wasp (CV-7), which also included: San Francisco (CA-38), Salt Lake City (CA-25), Guadalupe (AO-32), Aaron Ward (DD-483), Farenholt (DD-491), Buchanan (DD-484), Lansdowne, Duncan, Lardner and Laffey. The task force shaped a course eastward of the New Hebrides Islands intending to meet with TF 17 formed around Hornet (CV-8). Juneau and TF 18 joined TF 17 on 12 September, forming TF 61. Shortly after joining company with the force, Juneau was notified of an enemy carrier 500 miles northward. TF 61 was then ordered to proceed to San Cristobal Island [Makira] to cover the movement of marine reinforcements to Guadalcanal.

On 13 September 1942, Juneau was proceeding with TF 18 and steaming, in calm seas, in her designated area of patrol, as Wasp conducted routine carrier operations. On 14 September, enemy seaplane contact was reported in the vicinity of the task force. At 1440, Wasp launched an attack/search group of 26 planes but it was later reported that enemy forces in the area had rerouted. On 15 September, at 1220, Wasp reported that it shot down a Japanese scout bomber. At approximately 1444, however, a flash and two explosions were observed on the starboard side, amidships of Wasp. The Japanese submarine I-19 (Lt. Cmdr. Kinashi Takakazu, commanding) hit Wasp with a salvo of three torpedoes. At the time of the explosion Wasp was steaming approximately 2,500 yards from Juneau. Following the explosion, the cruiser received orders to circle Wasp, a mission she immediately executed while also scouring the area for any signs of enemy submarines. As Juneau crossed Wasp’s wake she observed numerous men in the water and slowed, but was ordered to continue patrolling, with the screening destroyers moving in to rescue survivors.

At 1555, submarine contact was made to the east of Wasp and confirmed by Lardner. Juneau laid a pattern of depth charges and hauled clear but no evidence of enemy damage was observed. Meanwhile, Swenson noted that Wasp “was not making progress,” and was in the process of being abandoned. Juneau remained in the area to protect Wasp from a potential enemy air attack. Beginning at 1716, a Grumman TBF Avenger made three attempts to drop a message to Juneau but all the efforts failed. By 2000, Wasp was burning fiercely and Lansdowne scuttled her with a torpedo. Juneau and some of the destroyers managed to pull 1,910 of the downed aircraft carrier’s survivors out the water. In short order, Juneau, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and Helena (CL-50), were steaming in column headed for Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu]. Juneau arrived at Espíritu Santo on 16 September, and disembarked the wounded and other survivors she had on board. The cruiser was swiftly ordered back out to sea but due to the darkness she was unable to leave that night because of the improbability of clearing the harbor at night without navigational aids.

Juneau was underway from Luganville [Santo] by the early morning hours of 17 September 1942, proceeding in company with San Francisco, Lardner, Lansdowne, Duncan and Farenholt. By 1645 the group had joined with TF 17 at 17°44'S, 167°48'W. Juneau assumed her station with TF 17 (Rear Adm. George D. Murray) as a screen for Hornet.

Beginning on 18 September 1942, Juneau accompanied TF 17 as it executed carrier operations and patrols in the vicinity of New Caledonia and the New Hebrides. Although Hornet’s planes engaged the enemy, for Juneau’s part, several uneventful weeks passed with little to report. A periscope sighting on 18 September prompted an embarrassing barrage fired from one of her port K-guns. On 19 September, she picked up a sound contact but following a drop pattern consisting of three charges, the propeller noise faded. On 26 September, the ship anchored at Dumbéa Bay in southwestern New Caledonia, occupying berth 43 for several days.

In the late morning on 2 October 1942, Juneau departed Dumbéa Bay in company with TF 17 and shaped a northwesterly course to pass westward of New Caledonia. Hornet was tasked with raiding enemy vessels near the Buin and Faisi area of the Solomons on 5 October. The ships arrived in their designated zone on 5 October, and at sunrise, at 0623, Hornet’s planes took off to carry out strikes. Confirmation of enemy contact was made; Juneau maintained her station screening Hornet. Following the raid, Juneau and the task force resumed patrolling and conducting carrier operations. While few events of particular import to Juneau took place over the course of the next week she did receive her first mail delivery in three and a half months on 15 October, which consisted of a whopping 84 bags. On 16 October, she proceeded with her task force to the waters south of the Solomon Islands so that Hornet could join in carrier attacks supporting the marine garrison at Guadalcanal.

At 15°35'S, 170°41'E, on 24 October 1942, Juneau and TF 17 combined with TF 16, and formed TF 61 composed of: Hornet, Enterprise (CV-6), South Dakota, Portland (CA-33), Northampton (CA-26), Pensacola (CA-24), San Juan (CL-54), Porter (DD-356), Mahan (DD-364), Lamson (DD-367), Conyngham (DD-371), Shaw (DD-373), Cushing (DD-376), Smith (DD-378), Preston (DD-379), Maury (DD-401), t, San Diego (CL-53), Hughes (DD-410), Anderson (DD-411), Mustin (DD-413), Russell (DD-414), Morris (DD-417), Barton (DD-599), and Juneau. During the night of the 24th the TF passed between Fatutaka Island and Pandora Bank. While cruising with TF 17 approximately five miles southwest of TF 16, Juneau and the others received reports of a large enemy surface force in the vicinity.

In the early morning hours of 26 October 1942, Juneau and her consorts were embroiled in what would later become known as the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. During the night of 25 October, the Japanese had made headway on Guadalcanal. As a part of the response to that, Juneau and the other ships of TF 61 deployed to the north of the Santa Cruz Islands to prevent enemy forces from furthering their gains there.

Hornet and Enterprise’s planes set out early in the day, identified an enemy fleet and attacked it ultimately damaging two carriers, one battleship, and three cruisers. While the attack was underway enemy planes had also located TF 61. Juneau’s crew was called to general quarters at 0756, when word was received that Northampton made radar contact with a formation of approaching enemy aircraft. At 1010, the real action began for the Hornet group, of which Juneau was a part, when Japanese planes initiated a dive bombing attack on Hornet. According to Swenson, Juneau’s crew saw Aichi D3A carrier bombers and Nakajima B5N2 Type 27 carrier attack planes attack Hornet. Juneau’s torpedo officer reported that he observed at least two torpedoes pass astern of Hornet and claimed to have also seen two suicidal enemy crashes hit the carrier—although these were not confirmed.

During the enemy onslaught Juneau and the task force’s other screens established a heavy shield of anti-aircraft fire and together, in total, splashed some 20 planes. By 1020, Swenson reported that Hornet was smoking badly and listing roughly ten degrees to starboard; within 15 minutes she lay dead in the water. Juneau, as well as the other cruisers and destroyers, circled the helpless Hornet in a counter clockwise pattern. At 1108, another Japanese carrier bomber attacked Hornet but failed to hit their target. Juneau and the other escorts opened fire with all their batteries but the bomber managed to escape. At 1129, two more enemy planes were seen approaching but both retreated after being fired upon.

Northampton passed a tow line to Hornet at 1143; ten minutes later Juneau received word via signal light to go to Enterprise. In the days following the action it was discovered that the signal light had actually not been meant for Juneau. Nonetheless, Juneau had shaped a course for Enterprise but, as she started her departure, a Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless (BuNo 4656) from Scouting Squadron (VS) 8, piloted by Lt. Cmdr. William T. Widhelm, landed in the water 1,000 yards off her starboard bow and she quickly rescued the two wounded crewmen. Juneau resumed her course and within 20 minutes encountered an enemy Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 carrier fighter, which she shot down at 2,000 yards. Upon sighting Enterprise at 1231, Swenson observed that the carrier appeared to have a slight list. At 1233, more enemy planes approached and Juneau commenced firing. By 1338, planes from Hornet were returning and began landing in the water as Enterprise proved unable to accommodate them. Destroyers present began rescuing aviators from the water.

At 1524, Juneau arrived on station with Enterprise, which had just launched additional planes. The ship’s log reported that during the action photographs were taken and that in all Juneau had fired 665 rounds of 5-inch ammunition and 38 anti-aircraft rounds. In completing his report of the day’s events Swenson gave the following recommendations for future screening operations, “stationing a screen at least 3,000 yards would facilitate handling of the 5-inch better but would also give unrestricted searoom for the carrier to maneuver. This would greatly eliminate the necessity of the screening ship having to perform rapid maneuvers and would thereby increase the effectiveness of AA [antiaircraft] fire.”

The day after the battle Juneau was steaming with Enterprise, which was conducting air operations in the same region. Between 1608 and 1649, burial services were conducted and the colors were flown at half-mast. For the next several days the task force continued to patrol in the vicinity of the New Hebrides and New Caledonia. On 31 October 1942, Juneau anchored at Dumbéa Bay and took on fresh stores.

Juneau departed Nouméa, New Caledonia, on 8 November 1942, as part of TF 67, escorting reinforcements en route to Guadalcanal; Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner commanded the task force. The ships arrived at Guadalcanal on 12 November, and Juneau took her place as a screening vessel for transports offloading in the area. In the early afternoon, 30 Japanese planes swarmed the task force. Juneau and the other screens put up a formidable anti-aircraft defense in which Juneau, alone, claimed to have shot down six enemy torpedo planes. Shortly thereafter American fighters swooped in and fired on the surviving attackers; in the end only one enemy bomber escaped the action unscathed. Following the mêlée, a majority of the U.S. cruisers and destroyers in the area cleared out in anticipation of the arrival of a large enemy surface force headed to the vicinity with the purpose of bombarding American forces on Guadalcanal.

Rear Adm. Daniel J. Callaghan and a rather small task force of U.S. naval vessels, 13 to be precise, including Juneau, remained in the area. In the early morning hours of the next day they engaged a Japanese bombardment force led by Vice Adm. Abe Hiroaki, which consisted of the battleships Hiei (Abe’s flagship) and Kirishima; the light cruiser Nagara; and 11 destroyers: Samidare, Murasame, Asagumo, Teruzuki, Amatsukaze, Yukikaze, Ikazuchi, Inazuma, Akatsuki, Harusame, and Yūdachi. Shortly after midnight, Abe’s flotilla appeared from out of a rain squall, practically on top of the American ships and a violent foray erupted in the darkness. The Japanese were out of formation and as they had been expecting to launch a shore bombardment they were not prepared to engage an American surface force—thus they were caught completely by surprise. The U.S. ships were also awkwardly positioned as they had been unsure of the exact composition of the Japanese battle line; this resulted in both forces nearly colliding. Once the guns sounded the battle rapidly became every ship for herself. Atlanta (CL-51) was positioned in a way that she became the immediate focus of concentrated enemy fire and she was quickly overwhelmed; Rear Adm. Norman Scott was killed on her bridge shortly after the action commenced.

Juneau fired off some 5-inch and 20-millimeter rounds and then she was struck on her port side by a torpedo from the Japanese destroyer Murasame, “below the armor belt and above the rolling chocks.” According to Lt. Roger W. O’Neill, one of Juneau’s medical officers, the hit from the concussion caused “a terrific jolt,” that he said “buckled the deck just aft of turret eight,” and threw three depth charges overboard. Severely damaged, Juneau lost her steering, which nearly caused her to collide with Helena. Miraculously Juneau managed to withdraw from the fray. After the damaged ship retired, the ongoing engagement lasted only another 40 minutes or so. Capt. Gilbert C. Hoover, the commanding officer of the cruiser Helena, emerged as the senior surviving officer of the group and gave the overall order to withdraw and regroup. Several ships were badly damaged, Laffey and Barton had been sunk; Cushing and Monssen (DD-436) were burning but still afloat; Atlanta and Aaron Ward lay dead in the water. Rescue efforts went on throughout the day and approximately 1,400 survivors were eventually brought ashore to Guadalcanal.

As survivors of the night’s engagement were being pulled from the water, the badly damaged Juneau was steaming through the Sealark Channel on only a single screw. She was initially headed towards the Island of Malaita where Swenson hoped to find a cove where some temporary repairs could be completed before making a dash for Espíritu Santo. By dawn on the 13th, Juneau caught sight of the cruisers San Francisco, and Helena, as well as the accompanying destroyers O’Bannon, Fletcher and Sterett (DD-407). After exchanging signals Juneau joined the formation and shaped a course for Espíritu Santo. The cruiser struggled through the water; the damage she sustained from the torpedo hit knocked out much of her power and she was ten to twelve feet down by the bow and listing. A few hours after dawn, at 0725, Juneau transferred Lt. O’Neill, PhM1c Orrel G. Cecil, PhM2c Theodore D. Merchant, and PhM1c William T. Sims by whaleboat to San Francisco to help with the high number of wounded.

By the late morning of 13 November 1942, Juneau was steaming 800 yards from the starboard quarter of the also damaged San Francisco. At 10°33'S, 161°03'E, at 1101, Japanese submarine I-26 (Cmdr. Yokota Minoru, commanding), fired three torpedoes, meant for San Francisco. The first crossed San Francisco’s bow and barely missed Juneau’s stern. The second also missed San Francisco but hit Juneau, on her port side, amidships, near her previous injury. The third came aft of both ships but missed them.

SM1c Lester E. Zook, one of Juneau’s few survivors later recalled that the “decks were almost awash,” before the torpedo struck. Within seconds of the hit a massive explosion rocked Juneau; it was believed that her magazine ignited. Accounts from sailors on board the other ships, present at the attack, indicated that not only was the blast immense “blowing debris far into the air,” but that within nearly 20 seconds Juneau was gone; as one eyewitness stated “it seemed almost instantaneous.” The last time Lt. O’Neill saw Juneau was when he looked out the small port of the admiral’s cabin on board San Francisco and saw “tremendous clouds of grey and black smoke,” but Juneau had disappeared.

There was a general consensus among eyewitnesses that no one could have survived the blast. Despite that perception there were survivors. Based on the accounts of some of those survivors it is estimated that of the 693 sailors on board at the time she was hit roughly 115 of them were stranded in the water following the sinking of the ship. For those that had survived, however, their tribulations had only just begun.

San Francisco’s communications gear had been damaged during the earlier fighting and so she was unable to send any kind of warning to Juneau after spotting the torpedoes. In fact, of all the ships present in the group at the time only Fletcher was capable of antisubmarine operations. O’Bannon also still had antisubmarine capabilities but had been detached from the group earlier in the day to contact higher headquarters without revealing the position of the rest of the group. With Juneau seemingly obliterated, an enemy submarine nearby, the threat of enemy aircraft in the area, as well as a serious danger of revealing their location Capt. Hoover gave the order to press on as quickly as possible. In the days following the incident, Hoover’s decision to not attempt an immediate rescue was markedly questioned by his superiors; however, it should be remembered that the decision was made by an experienced, decorated naval commander and was done largely in order to prevent Juneau’s tragedy from being compounded with the loss of yet another crew of American sailors.

Following the catastrophic explosion on board Juneau, those who emerged from the water found themselves in a giant vortex of water thick with oil. The men who managed to stay afloat clung to what debris, or few life jackets and rafts they could find. Accounts from survivors indicate that many of them were seriously injured, some with “their arms and legs torn off.” A group of them led by Lt. John T. Blodgett (who did not ultimately survive) did their best to pull what rafts could be found together and try to form the men into a single body in order to help the wounded and perhaps better fend off sharks. All the survivors stated that on the first day they saw a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress fly overhead, which flew low and waved at them to let them know they knew they were there. Most of the survivors’ accounts also stated that they knew why San Francisco and the rest of the group pressed on, with the enemy submarine in the area, but that they “felt sure that help would come at any time,” that hope surely kept many of them alive.

A large group of the surviving sailors stayed together, but exposure, exhaustion, shock, dehydration, and shark attacks quickly thinned the ranks and over the course of the next seven days several groups separated from the main body. Lt. Charles N. Wang, SM2c Joseph F. Hartney, and Sea1c Victor J. Fitzgerald broke off from the main group to attempt to swim ashore to a nearby island they spotted—Santa Catalina. They made it to shore and were rescued by natives on the island, on 19 November, and were eventually picked up by American forces.

SM1 Zook, Sea1c Wyart B. Butterfield, MM2c Henry J. Gardner, Sea2c Frank A. Holmgren, and CGM George I. Mantere remained with the main group and were rescued at sea on 19 November, by a PBY Catalina, and were later taken to the base hospital at Tulagi. On more than one occasion the members of this group had watched one of their fellow sailors get eaten alive by sharks after leaving the safety of a raft. Despite such dangers, on the day of their rescue Sea1c Butterfield left his raft in order to retrieve a life jacket, food, and water, dropped by a PBY. Pursued by sharks during the endeavor, he later recounted that he was sure that “he never swam so fast in his life.”

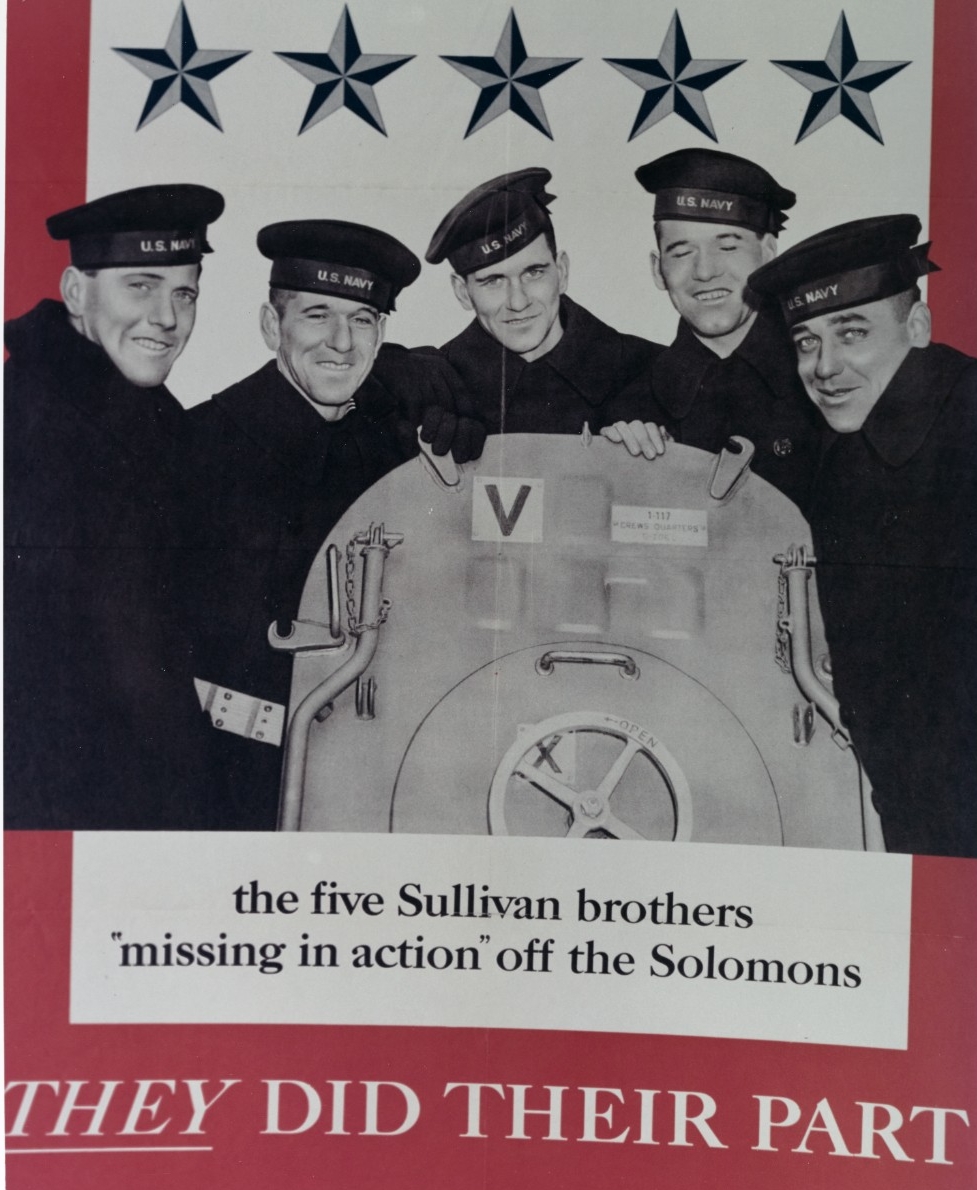

Sea2c Allen Clifton Heyn, and Sea1c Arthur T. Friend, were also separated from the main group and were the last two to be rescued at sea. On 20 November, they were picked up separately by the destroyer seaplane tender Ballard (DD-267), which had been dispatched to the area to search for Juneau survivors. S1 Friend was rescued at 0838 and Sea2c Heyn was rescued at 1045. In his interview in 1944, Sea2c Heyn gave a vivid account of his experience. He recalled that “at night you had to keep under the water to keep warm,” but still had to be on guard for sharks. It is from Heyn that the primary account of the last remaining Sullivan brother was given. The five Sullivan brothers all perished as a result of Juneau’s sinking. The shock of such a large singular sacrifice by one family made the brothers quite famous following the tragic event. Their story was adapted into an American biographical war film in 1944: The Fighting Sullivans [originally The Sullivans], directed by Lloyd Bacon.

Based on the other survivor accounts it is believed that GM2c George T. Sullivan, the oldest brother, was the only one to survive the sinking. According to Heyn’s account George started acting unusual one day and at some point said he was going to take a bath and then proceeded to strip off his clothes and drifted out into the water where he was eventually eaten by a shark. The military’s focus on the Sullivan family’s sacrifice was used in large part to honor the sacrifice of all the sailors lost with Juneau. All told, ten of the 693 U.S. sailors on board Juneau at the time of her sinking survived; taking into account Lt. O’Neill and the three corpsmen whom Juneau transferred over to San Francisco that makes 14 survivors of the original crew.

After departing the area at 1121 on 13 November 1942, Hoover had a signal relayed to a passing B-17 regarding Juneau’s fate as well as her last known coordinates. The Flying Fortress attempted to land that day at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, but was waved off and proceeded instead to Espíritu Santo. The crew included the information about Juneau in their routine report but for unknown reasons it was not passed on. The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal continued on through the 14th and 15th of November; with Japanese forces still attempting to carry out their original mission and U.S. forces endeavoring to stop them. In the midst of those continuing operations and Juneau’s message for help being delayed to the next day it was certainly a tragic circumstance, in which her survivors were to find themselves in desperate straits and at the mercy of unforgiving seas.

Helena and the rest of her beleaguered group were haunted for the rest of their journey by submarine sightings, but managed to arrive at Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, without further incident at 1639, on 14 November 1942. Earlier in the morning Hoover had notified Rear Adm. Turner via TBS about Juneau and upon Helena’s arrival at Espiritu he also, notified Rear Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific Force. A review of TF 63 and Commander, South Pacific (ComSoPac), records confirms that both organizations were fully aware of Juneau’s sinking as of 14 November.

On 14 November 1942, ComSoPac sent dispatch 142202, ordering the destroyer Meade (DD-602) to proceed to the area of Juneau’s last known position to pick up survivors. Keeping in mind there was still a battle going on in the area, Meade was rerouted to conduct a bombardment; and on 15 November, she received orders to carry out an attack on Japanese transports, as well as, rescue the crew of a plane that went down in her immediate vicinity. By the end of the day on the 15th, Meade was en route to Tulagi with the survivors of the plane crash. Helena again sent a formal dispatch to ComSoPac on 15 November, and Meade again received orders instructing her to go to the area around San Cristóbal to search for Juneau survivors. Meade reported that she would begin her search of the area as soon as possible after dropping off the other survivors she had on board at Tulagi.

Meade set out to search for Juneau survivors by 0515, on 16 November 1942. After conducting a full day’s search, poor weather and low fuel, caused Meade to break off her efforts just after nightfall. Meanwhile, aircraft, as they had been doing for several days, continued looking for stranded sailors. There was at last a sighting on 18 November, and Ballard was tagged for the rescue. On the 19th, there was a direct sighting of Juneau survivors who were consequently picked up by a PBY. Another group was spotted that same day but bad weather delayed a pick up; the next day on 20 November, Ballard, along with some planes set out to pick up the last of Juneau’s survivors.

Just as the search for Juneau’s sailors was underway, Hoover’s own ordeal had just begun. Upon learning of the details of Juneau’s sinking, Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Commander, South Pacific Area, determined that Hoover had not acted properly. After arriving at Espiritu Santo on 14 November 1942, Hoover was ordered to go to Halsey’s headquarters at Noumea where he was questioned by Turner, Fitch, and Vice Adm. William L. Calhoun. Halsey believed that Hoover should have set up an anti-submarine screen around Juneau’s wreckage, broken radio silence, and initiated a rescue.

Hoover defended each of his actions pointing to the lack of operable ships, and the immediate danger from enemy submarines, as well as nearby enemy aircraft. Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, proved more understanding of Hoover’s decision and recommended he remain in command at sea once he had received rest. Nonetheless, Halsey had Hoover detached from Helena on 23 November, and sent stateside. Hoover eventually assumed command of the Naval Ammunition Depot, Earle, N.J.

In his autobiography Admiral Halsey’s Story, published in 1947 and based on his candid memoir, Halsey recanted his decision to remove Hoover stating “I cannot close this account of the Battle of Guadalcanal without adding my confession of a grievous mistake. I have already confessed it officially; now I do so publicly… when I reviewed the case… I concluded that I had been guilty of an injustice. I realized that Hoover’s decision was in the best interests of victory. I so informed the Navy Department… I deeply regret the whole incident.” Indeed, many more lives might have been lost that day had Hoover not had the courage to make a gut-wrenching decision that all Naval officers bear the potential burden of having to make.

The story of Juneau’s tragic sinking and the harrowing tales of those who survived have long been seared into the USN’s cultural memory. Her sacrifice during the largest conflict in human history has had an enduring legacy. In addition to the ships of her name that have come after her, two ships were named in relation to the sinking of the first Juneau. Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) was named in honor of Capt. Swenson, and The Sullivans (DD-527) honored the Sullivan brothers. The City of Juneau, Alaska, also maintains a memorial to the fallen sailors of Juneau.

Ultimately, Juneau’s wreck was discovered and photographed by the crew of the Research Vessel Petrel, owned by Paul G. Allen, Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist, on Saturday, 17 March 2018; located 4,200 meters (13,800 feet) below the surface in the vicinity of the Solomon Islands.

| Commanding Officer | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Lyman K. Swenson | 14 February 1942 |

Jeremiah D. Foster

15 June 2018