Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On July 26, 1946, Joy Bright Hancock was promoted to captain and appointed director of the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). As the third and ultimately last director, she took a leading role in the preparation and promotion of what eventually would became the “Women’s Armed Services Integration Act,” signed by President Harry S. Truman on June 12, 1948. After the bill became law, women were integrated directly into various components of the Navy, receiving the same pay and privileges as men, but were assigned shore duty only—restricted from sea duty and combat flying. For the remainder of Hancock’s career, she served as an advisor on women’s affairs and as a key figure in the activation of more than 500 officers and 6,000 enlisted women. She was transferred to the retired list, effective June 1, 1953, and was awarded the Legion of Merit, “For exceptionally meritorious conduct … as director of the Women’s Reserve of the Naval Reserve from July 1946 to October 1948, and as assistant chief of naval personnel for women from October 1948 to June 1953.…” The citation continued in part:

“Exercising organizational and administrative ability of the highest caliber, Captain Hancock served with distinction throughout the transition period in which women became a regular component of the United States Navy and was eminently successful in initiating the basic plans and in overcoming the many varied and complex problems which confronted her during the inaugural stages incident to establishing the women as an integral part of the naval service… She was directly instrumental in the formulation of plans and policies affecting the selection and training of the women, together with their utilization, administration, welfare and housing. Skillfully welding the personnel under her leadership into a high efficient unit, she maintained a coordinated and effective command and contributed immeasurably to the success achieved by women in the various fields to which they were assigned throughout the naval service.…”

Hancock was born in Wildwood, New Jersey, on May 4, 1898. She attended high school in Wildwood; George Washington University and Crawford Foreign Service School in Washington, DC; Pierce School of Business Administration in Philadelphia; and the Paris branch of New York School of Fine Arts. She also had flying instruction at the Henry Berliner Aviation School, Washington, DC. During World War I, as a yeoman (F) first class, she served at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden, New Jersey, and later as chief yeoman, attached to the U. S. Naval Air Station, Cape May, New Jersey. In September 1919, she left the Navy and subsequently worked as a civilian employee at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey. From 1934 until the fall of 1942, she was the civilian chief of the Editorial and Research Section, Bureau of Aeronautics, Navy Department, and special assistant to the chief of that bureau. On Oct. 15, 1942, she was commissioned a lieutenant in the Women’s Reserve and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander on Nov. 26, 1943; to commander, March 5, 1945; and to captain when she became director of the WAVES after World War II. On Oct. 15, 1948, she was one of eight women sworn into the regular Navy under the Women’s Armed Service Integration Act.

Hancock was married three times during her lifetime. On a tragic note, her first and second husbands were killed in , on which they were serving. Her first husband, Lt. Charles G. Little, was killed when ZR-2 crashed over the Humber River, England, just ten months after they were married. Her second husband, Lt. Cmdr. Lewis Hancock, Jr., died in the crash of Shenandoah (ZR-1) in Ohio on Sept. 3, 1925. Her last husband, Vice Adm. Ralph A. Ofstie, who she married after retirement, died in November 1956. All three of her husbands were highly decorated naval aviators, and her first two husbands were Navy Cross recipients. Hancock passed away at Bethesda Naval Hospital in 1986 at 88 years of age. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Indianapolis Tragedy

On July 30, 1945, Japanese submarine I-58 sank USS Indianapolis (CA-35) with two torpedo strikes, northeast of Leyte. Only 316 of her 1,195 crew survived the attack and the subsequent fight for survival. Due to communication and other errors, the loss of Indianapolis went unnoticed until survivors were spotted by a passing aircraft days later. Prior to her sinking, Indianapolis had just delivered Tinian, the components of the Hiroshima atomic bomb, that would ultimately help end World War II in the Pacific. After the Portland-class heavy cruiser fell prey to the Japanese submarine shortly after midnight, fire and chaos ensued and in the next 12 minutes, 330 of the crew went down with the ship as it quickly sank, while the rest, approximately 880 men, were left alone in the Pacific in the middle of the night. For the next few days, without food or water, suffering exposure, dehydration, drowning, and shark attacks, the crew battled the elements and clung to life as best they could before they were finally rescued.

When the ship did not reach Leyte on July 31 as scheduled, no report was made that she was overdue. This omission was due to a misunderstanding of the Movement Report System. Thus, it was not until at 10:25 a.m. on Aug. 2 that the survivors were finally sighted, mostly kept afloat by life jackets, although there were a few rafts that had been cut loose before the ship went down. The pilot who discovered them immediately dropped a life raft and a radio transmitter. All air and surface units capable of rescue operations were dispatched to the scene at once, and the surrounding waters were thoroughly searched for survivors. Upon completion of rescue operations on Aug. 8, a radius of 100 miles had been searched by day and by night. Capt. Charles B. McVay, commanding officer of Indianapolis, was court-martialed for the loss of his ship, but posthumously exonerated by congressional resolution in 2000. All personnel involved in the failure to report the ship's absence from Leyte were also exonerated, after all the evidence had been carefully weighed.

Commissioned in November 1942, Indianapolis received 10 battle stars for her service during the war. She participated in such naval battles as the Aleutians campaign, Gilbert Islands operation, Battle of Saipan, Battle of the Philippine Sea, occupation of Guam and Tinian, Battle of Iwo Jima, and the Battle of Okinawa. The ship also served as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ship of state during the 1930s and as Adm. Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet flagship between 1943 and 1944.

On Aug. 12, 2017, a team of civilian researchers led by entrepreneur and philanthropist Paul G. Allen announced they had found the wreck of Indianapolis. The wreck was located by the expedition crew of research vessel Petrel, which was owned by Allen, 5,500 meters below the surface, resting on the floor of the North Pacific Ocean. “To be able to honor the brave men of the USS Indianapolis and their families through the discovery of a ship that played such a significant role in ending World War II is truly humbling,” said Allen shortly after the discovery. “As Americans, we all owe a debt of gratitude to the crew for their courage, persistence and sacrifice in the face of horrendous circumstances. I hope everyone connected to this historic ship will feel some measure of closure at this discovery so long in coming.” Allen and his crew had previously located a number of lost World War II American ships to include USS Ward (DD-139) and USS Juneau (CL-52). Allen passed away in 2018 after a long bout with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Even in the worst defeats and disasters there is valor and sacrifice that deserves to never be forgotten,” said Sam Cox, director of the Naval History and Heritage Command. “They can serve as inspiration to current and future Sailors enduring situations of mortal peril. There are also lessons learned, and in the case of Indianapolis, lessons re-learned, that need to be preserved and passed on, so the same mistakes can be prevented, and lives saved.”

Nautilus Transits Under North Pole

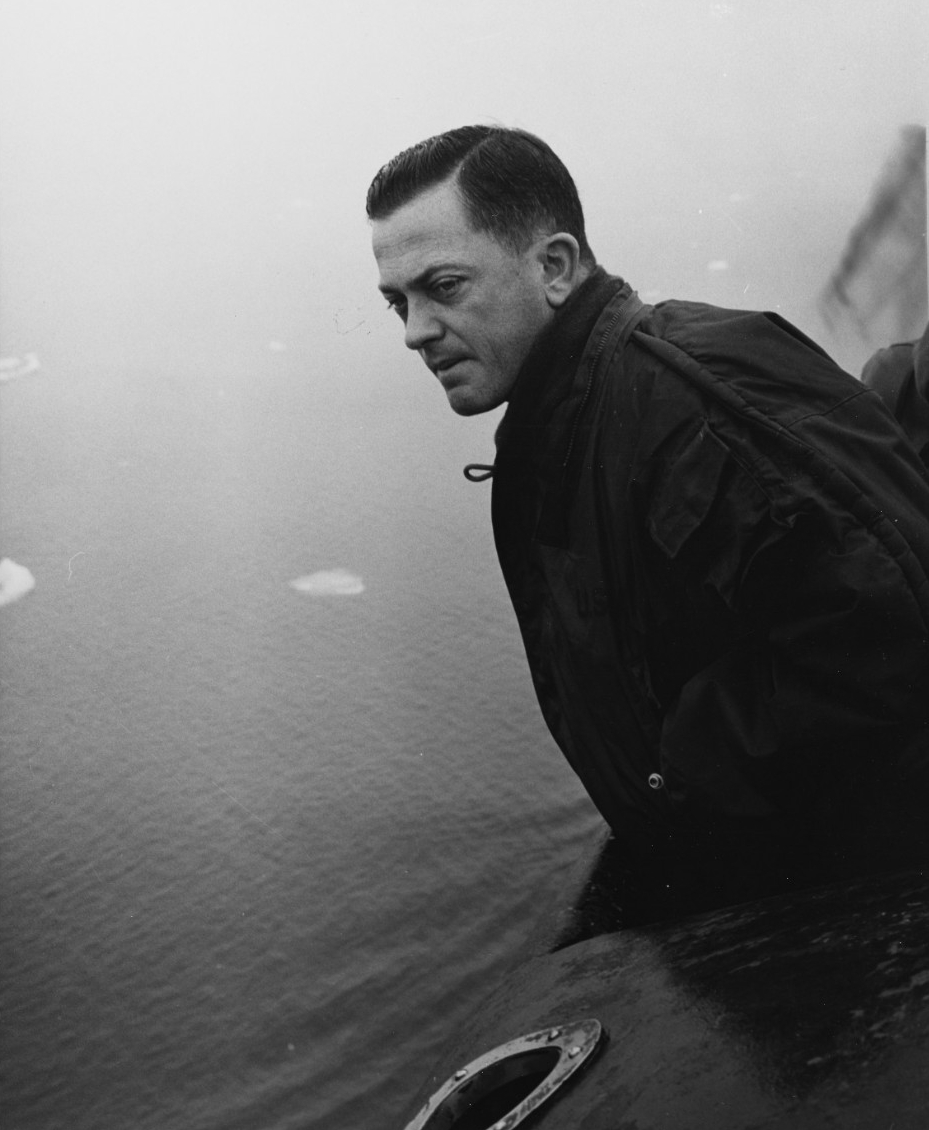

On Aug. 3, 1958, USS Nautilus (SSN-571) became the first submarine to a conduct a fully submerged transit under the geographic North Pole during the highly secretive Operation Sunshine. “For the world, our country, and the Navy—the North Pole," declared the boat's commanding officer, Cmdr. William R. Anderson. The mission had been personally authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a response to the USSR's Sputnik program, and he subsequently awarded Nautilus the Presidential Unit Citation. Nautilus began the mission on June 9 when she departed Seattle. However, the first attempt was blocked by drift ice in the relatively shallow waters of the Chukchi Sea, and the submarine made way to Pearl Harbor. Her second attempt, begun on July 23, proved successful. Nautilus submerged in the Barrow Sea on Aug. 1, transited the North Pole, and, after running submerged an additional 96 hours, surfaced off Greenland on Aug. 7.

The construction of Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear powered submarine, was made possible by the successful development of a nuclear propulsion plant by a group of scientists and engineers, under the leadership of Capt. Hyman G. Rickover, at the Naval Reactors Branch of the Atomic Energy Commission. After sea trials and preliminary acceptance by the Navy, Nautilus headed south for shakedown on May 10. While en route to Puerto Rico, she remained submerged, traveling 1,381 miles in 89.8 hours, the longest submerged cruise to that date by a submarine and at the highest sustained submerged speed ever recorded for a period of more than one hour’s duration. The following year, Nautilus operated out of Naval Submarine Base New London, Connecticut, where the effects of a submarine with increased speed and endurance were tested on contemporary anti-submarine warfare practices. The study found that anti-submarine practices, such as were used during World War II, were ineffective against a submarine that did not need to surface, could dive deeper, and could clear a search area in record time.

On Feb. 4, 1957, Nautilus logged her 60,000th nautical mile. It also marked another first for the boat, as the submarine was put into the Electric Boat Company Division of General Dynamics Corporation at Groton to replace the nuclear fuel core in her Westinghouse Electric submarine thermal reactor. In early April, Nautilus operated off Bermuda with USS Seawolf (SSN-575)—the second nuclear-powered submarine—before departing for the U.S. West Coast on May 15. While there, Nautilus participated in multiple exercises designed to acquaint the units of the Pacific Fleet with the capabilities of nuclear submarines. She returned to New London on July 21. On Aug. 19, Nautilus departed New London for her first voyage under the Arctic polar ice pack. The 1,383-mile journey was significant, because previously, conventional U.S. diesel-electric submarines did not travel to the frozen northern oceans since they could not travel freely under ice. The opening of the Arctic to Navy submarines allowed access to the previously protected coastal waters of the Soviet Union.

After her record-breaking transit of the North Pole in 1958, Nautilus continued to focus on evaluation tests for anti-submarine warfare improvements and various NATO exercises in the Atlantic. In the spring of 1966, she again entered the record books when she logged her 300,000th mile underway. During the following 12 years, Nautilus was involved in a variety of developmental testing programs while continuing to serve alongside many of the more modern nuclear-powered submarines she had preceded.

On April 9, 1979, Nautilus departed Groton on her final underway, steaming south to the Panama Canal via Guantanamo Bay and Cartagena, Columbia. From there, she cruised north and reached Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California, on May 26, to begin inactivation procedures. The ground-breaking submarine decommissioned on March 3, 1980.

In recognition of her pioneering role in the practical use of nuclear power, Nautilus was designated a National Historic Landmark by the Secretary of the Interior on May 20, 1982. Following an extensive historic ship conversion at Mare Island, the submarine was towed to Groton, arriving on July 6, 1985. There, on April 11, 1986, 86 years to the day after the establishment of the U.S. Submarine Force, historic ship Nautilus and the Submarine Force Museum opened to the public as the first exhibit of its kind in the world. The unique museum ship continues to serve as a dramatic link in both Cold War–era history and the birth of the nuclear age.

JFK’s Torpedo Boat Rammed, Crew Marooned

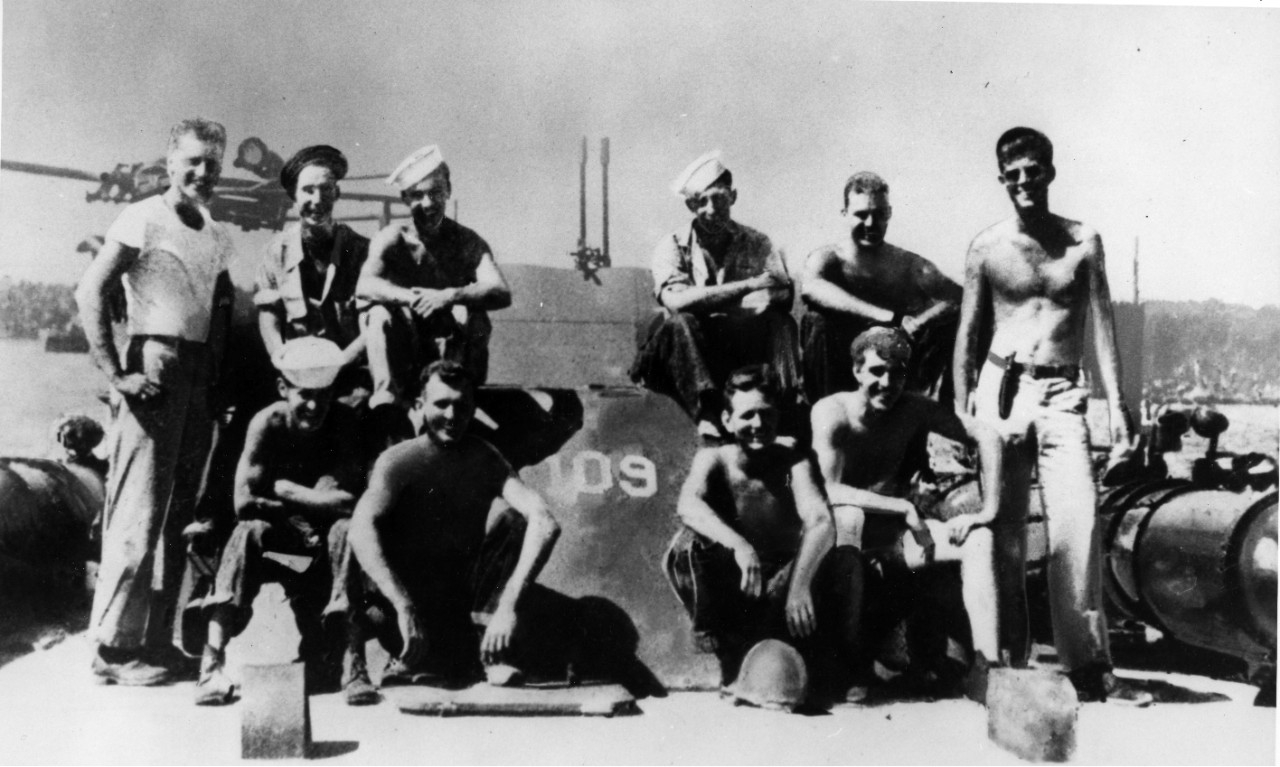

On Aug. 2, 1943, PT-109, commanded by Lt. (j.g.) John F. Kennedy, was rammed by Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which cut through the motor torpedo boat in Blackett Strait near Kolombangara Island, sending the crew into the water. Fire ignited spilled gasoline on the water some 20 yards around the wreckage and drove the crew in all directions. It quickly became clear that the forward half of the boat was still floating after the flames died down and Kennedy with five other members of the crew crawled back on board the hull. Shouting soon revealed three men were in the water some 100 yards to the southwest, while two others were an equal distance to the southeast. Kennedy swam to the group of three, where he found one man suffering from serious burns and another struggling to stay afloat with a water-logged life jacket. Trading his life belt to the latter Sailor, Kennedy towed the injured man back to the wreckage of PT-109. Returning to the scene, Kennedy helped tow the exhausted crewmembers back to the boat. Meanwhile, two other members of the crew towed the other two survivors back to the floating section of the boat. Two other members of PT-109 were never seen and presumed killed in the collision with Amagiri. All 11 survivors were clinging to the wreckage of PT-109 about four miles north and slightly east of Gizo anchorage. When it became obvious the boat remnants would sink, Kennedy decided to abandon ship and swim to a small island some four miles southeast of Gizo, hoping to avoid any Japanese garrisons. At about 2 p.m., the crew pushed off for land, towing the badly burned engineer and two non-swimmers on a float rigged from a wooden post which had been a part of the 37mm gun mount. Arriving on shore, the group took cover and set up a temporary camp.

That night, Kennedy grabbed a salvaged battle lantern, donned a lifejacket, and swam to a small island a half-mile to the southeast, then along the reef stretching into Ferguson Passage, where he tried unsuccessfully to intercept patrolling motor torpedo boats. Returning in the morning, he turned the lantern over to Ensign George Ross who swam the same route into Ferguson Passage that evening. He also had no luck and returned the next morning. When the remaining rations and all the local coconuts had been consumed, the survivors investigated a small islet west of Cross Island and took cover in the heavy brush the next day. Undaunted by the sight of a New Zealand P-40 strafing Cross Island itself, Kennedy and Ross swam to that island in search of food, boats, or anything which might prove useful to their party. At one point, the two men found a Japanese box with 30-40 bags of crackers and candy and, a little farther up the beach, a native lean-to with a one-man canoe and a barrel of water alongside. About this time, a canoe with two natives was sighted, but they paddled swiftly off despite all efforts to attract their attention.

During the night of Aug. 5, Kennedy took the canoe into Ferguson Passage, but found no PT boats. Returning home by way of Cross Island, where he picked up the food, he found two natives there with the rest of the group. After telling the natives in as many ways as possible that he was an American and not Japanese, Ensign Leonard Thom finally convinced them to help the crew. The natives were then sent with messages to the Allied coastwatchers on Wana Wana. One was a penciled note written the day before by Thom and the other a message written on a green coconut husk by Kennedy.

The next day, eight natives arrived with instructions from the coastwatcher for the senior naval officer to go with the natives to Wana Wana. After the natives dropped off food and other supplies, including a cooking stove, they hid Kennedy under ferns in a large canoe and paddled him to Wana Wana. The canoe reached its destination about 4 p.m. and later that night Kennedy rendezvoused in Ferguson Passage with PT-157. In company with PT-171, and guided by natives who knew passages through the reefs, the survivors were picked up by small boats later that evening. Everything went off smoothly and PT-157 returned the survivors to Rendova PT base by morning. Kennedy was later awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal “for extremely heroic conduct” while serving as commanding officer of PT-109.