Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Samuel B. Roberts Hits Mine, Valiant Crew Saves Ship

In the spring of 1988, USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) was in the Arabian Gulf participating in Earnest Will—an operation to protect reflagged Kuwaiti tankers during the Tanker War phase of the Iran-Iraq War. On April 14, Samuel B. Roberts was underway to meet USS San Jose (AFS-7) to replenish stores when a lookout, Seaman Bobby Gibson, spotted three mines ahead in an area that had already been swept by coalition minesweepers. Once he confirmed the ship had in fact entered a minefield, Cmdr. Paul Rinn, the ship’s captain, quietly ordered his crew to battle stations without sounding the alarm to avoid panicking them or triggering mines. He also ordered his crew that were below decks to come topside in the event of possible mine damage below the waterline. Rinn weighed his options and decided to attempt to follow the ship’s wake to exit the minefield. “I thought,” he afterward noted, “we came in that way so we probably could go out that way.” The ship reversed engines, however, at 4:49 p.m., hit an Iranian moored contact mine. The explosion lifted the ship into the air, drove its bow down into the water, and blew a 21-foot hole on the port side. The impact damaged the hull, deckhouse, and foundation structures, and burning fuel shot a column of fire from the stack. The blast shook the main engines from their mountings, flooded the engine room, opened cracks in the superstructure, and caused a split in the ship’s bulkhead between the main engine room and an auxiliary machinery room. The explosion thrust some Sailors up into the overhead and threw other crewmembers across compartments (helmets protected them from fatal injuries). Ten Sailors sustained severe injuries, and four were seriously burned. Rinn broke the metatarsal bone in his left foot from the shock wave of the blast as well. While considering whether to abandon the ship, Rinn noticed swarms of snakes and sharks in the water. This, among other factors, helped persuade him to stay and fight for the ship.

During the aftermath of the attack, Rear Adm. Anthony A. Less, commander of Joint Task Force Middle East/Middle East Force, radioed Rinn several times from his flagship, USS Coronado (AGF-11), and at one point asked him to evaluate the possibility of losing Samuel B. Roberts. “No higher honor,” Rinn replied, referencing when the Japanese sank the first USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) during the Battle of Leyte Gulf on Oct. 25, 1944. That ship’s survivors had pulled Cmdr. Robert W. Copeland, their commanding officer, from the water, and Copeland said he could think of “no higher honor than to have served with these men.”

Intensive training of the crew and their valiant dedication ultimately saved Samuel B. Roberts. “He is a master at damage control,” said Rear Adm. Less of Rinn, but the commander unassumingly paid tribute to his crew. “They never hesitated to do the right thing,” Rinn recalled, “and showed incredible bravery in the face of almost-certain death.” “Their successful battle against all odds,” said Adm. William J. Crowe Jr., Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “is the stuff of which naval tradition is made.”

In the aftermath, American, British, Dutch, French, and Italian ships swept the 10 miles surrounding the area where the frigate struck the mine, and then expanded their search another five miles, locating eight additional mines of Iranian origin. Lack of barnacles or marine growth on the devices revealed they were recently deployed. On April 17, Samuel B. Roberts was towed into Dubai for dry-docking and temporary repairs. Several months later, Dutch heavy-lift ship Mighty Servant transported the frigate to a dry dock at Bath Iron Works in Maine. On April 18, the U.S. Navy launched Operation Praying Mantis against Iranian targets in the Arabian Gulf in retaliation. In the one-day operation, the U.S. Navy destroyed two Iranian surveillance platforms, sank two of their ships, and severely damaged another.

On May 3, medals were presented to the crew of Samuel B. Roberts for their actions in saving the ship. Rinn received the Legion of Merit, and the crew received the Navy Unit Commendation award as well as the following individual awards: 10 Bronze Star Medals, 14 Navy Commendation Medals, and multiple Purple Hearts. In addition, Rinn was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal with Combat Distinguishing Device for his “superior performance and management of the wounded,” along with the U.S. Navy League John Paul Jones Inspirational Leadership Award. He also received an Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal.

After repairs were complete, Samuel B. Roberts was returned to service on Oct. 16, 1989. On Aug. 2, 1990, the Iraq army invaded Kuwait. Two weeks later, with Cmdr. John W. Townes in command, Samuel B. Roberts deployed in support of Operation Desert Shield, spending numerous days patrolling the Red Sea. When the Iraqis failed to meet the deadline to withdraw their troops from Kuwait, President George H. W. Bush announced combat operations would commence to liberate Kuwait. During the deployment, Samuel B. Roberts intercepted numerous merchant vessels, and its crew boarded and inspected more than 100 merchantmen. After coalition attacks devastated the Iraqis and they withdrew from Kuwait, Samuel B. Roberts returned to Newport, Rhode Island, where thousands greeted the crew to a heroes’ welcome home.

Following the ship’s return from Desert Storm, Samuel B. Roberts participated in several exercises and law enforcement patrols. From 2004 to 2008, the ship participated in drug interdiction and relief operations in the U.S. Southern Command’s area of responsibility. A highlight of the patrols came right away on Jan. 12, 2004, when the crew boarded a suspicious vessel and seized more than 7,000 pounds of cocaine. In September 2007, Samuel B. Roberts played a major role in the aftermath of Hurricane Felix that devastated northeastern Nicaragua. Its crew delivered tons of supplies and evacuated hundreds to nearby medical facilities. While deployed to African waters in 2010 and 2011, the ship spent months protecting mariners from pirates off the African east coast. Samuel B. Roberts was decommissioned on May 22, 2015.

Obsolete Navy Ratings, The Forgotten Bases of Ireland

Recently, NHHC published two new articles on its blog and website that cover obscure or lesser-known topics in U.S. Navy history. In the first article, Communication and Outreach Division’s (COD’s) Wendy Arevalo touches on seven unique and unusual Navy jobs that existed from 1871 through the mid-1980s. From pigeon trainer to nuclear weaponsman to airship rigger, these ratings all served a vital function in their day until they were phased out by technological advances. One such obscure rating that was recognized before World War I was the bugler. Established in 1871, the rating designated Sailors to perform bugler duties aboard Navy ships. At the time, buglers sounded calls for almost every activity on a ship. The Navy Manual for Buglers states that bugle calls are categorized as routine, emergency, or a combination of both. Examples of routine calls were “reveille,” “mess call,” “morning colors,” “evening colors,” and “Taps.” Emergency calls were “man overboard,” “general quarters,” and “abandon ship.”

Buglers, unlike U.S. Navy musicians, were not able to advance to petty officer. According to the pamphlet U.S. Navy Enlistment, Instruction, Pay, and Advancement, a bugler second class was paid $33 per month in 1917. During this era, the Navy offered a bugler course for recruits. To be eligible, prospective buglers needed only to have “some idea of music, have very good teeth, have good health, and clean record,” according to a Sept. 23, 1918, bugler course syllabus. When the Navy began installing better shipboard announcing systems on ships, it disestablished the bugler rating. In 1948, the sea service consolidated bugler duties under the quartermaster rating. For more, read “Some Obsolete Navy Ratings” at The Sextant.

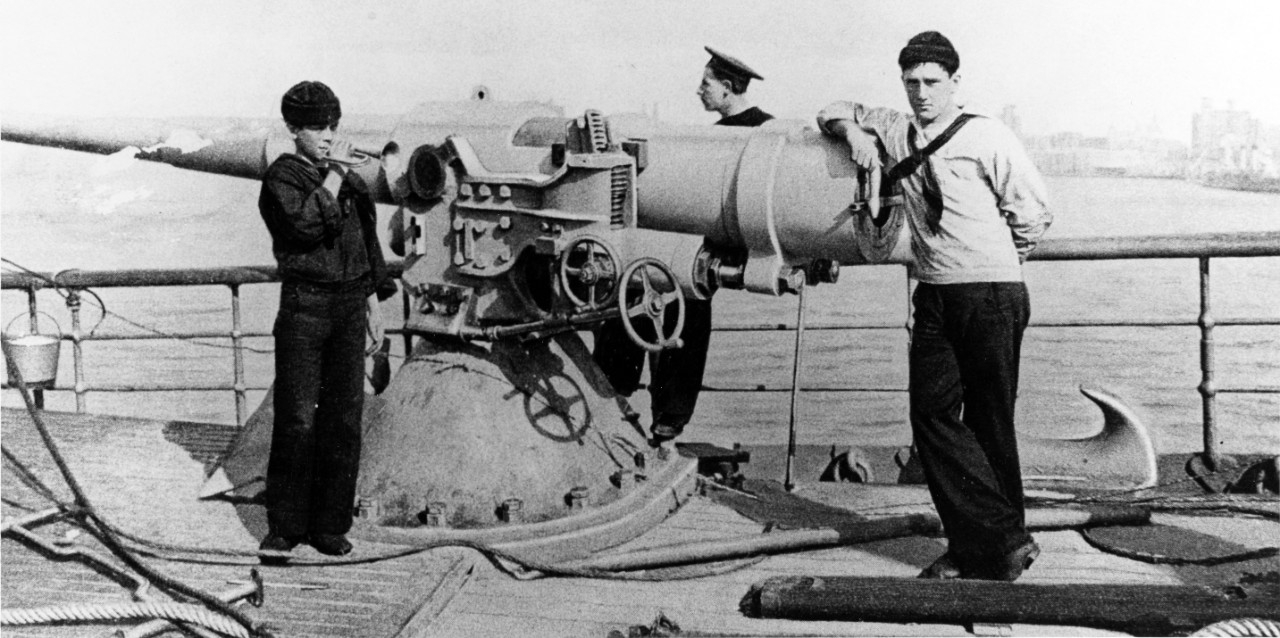

Also recently published is an article by COD’s Jacqueline S. Evans. Amid the devastation of World War I, the United States maintained a stance of neutrality for nearly three years. Woefully unprepared militarily, the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, in response to the Zimmermann note and Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare (USW). Although the USW policy was successful in depleting British supplies, it also severely weakened Germany diplomatically and contributed to America joining the war as U-boats frequently hit passenger ships, killing innocent civilians, including hundreds of Americans.

Much of the damage occurred in and around the Irish Sea, which was known as “U-boat Alley” due to the number of U-boats targeting ships going between Great Britain and the Atlantic Ocean. Although the United States did not immediately declare war, the Navy secretly began preparing for the inevitable in March 1917 by discussing cooperating with the Royal Navy. American officials knew that if the United States entered the war, not only would they need to secure the waters to send millions of troops and supplies to the front, they would also need to protect the seas to ensure Britain and other Allies continued fighting. At the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, Adm. William Sims set sail for London on March 31 to secure information on what the Royal Navy was doing to combat U-boats and its plans for including the U.S. Navy in the fight. Sims was shocked to learn of the severity of the U-boat crisis, including warnings that Germany could defeat Britain by November, and cabled Washington to urgently send all available destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland. Located on the southern coast of Ireland in Cork Harbor, Naval Base No. 6 in Queenstown was the primary naval base in Ireland for defending against submarines lurking in the waters off the British Isles and clearing the minefields in the Irish Sea. For more, read “The Forgotten Bases of Ireland” at NHHC’s website.

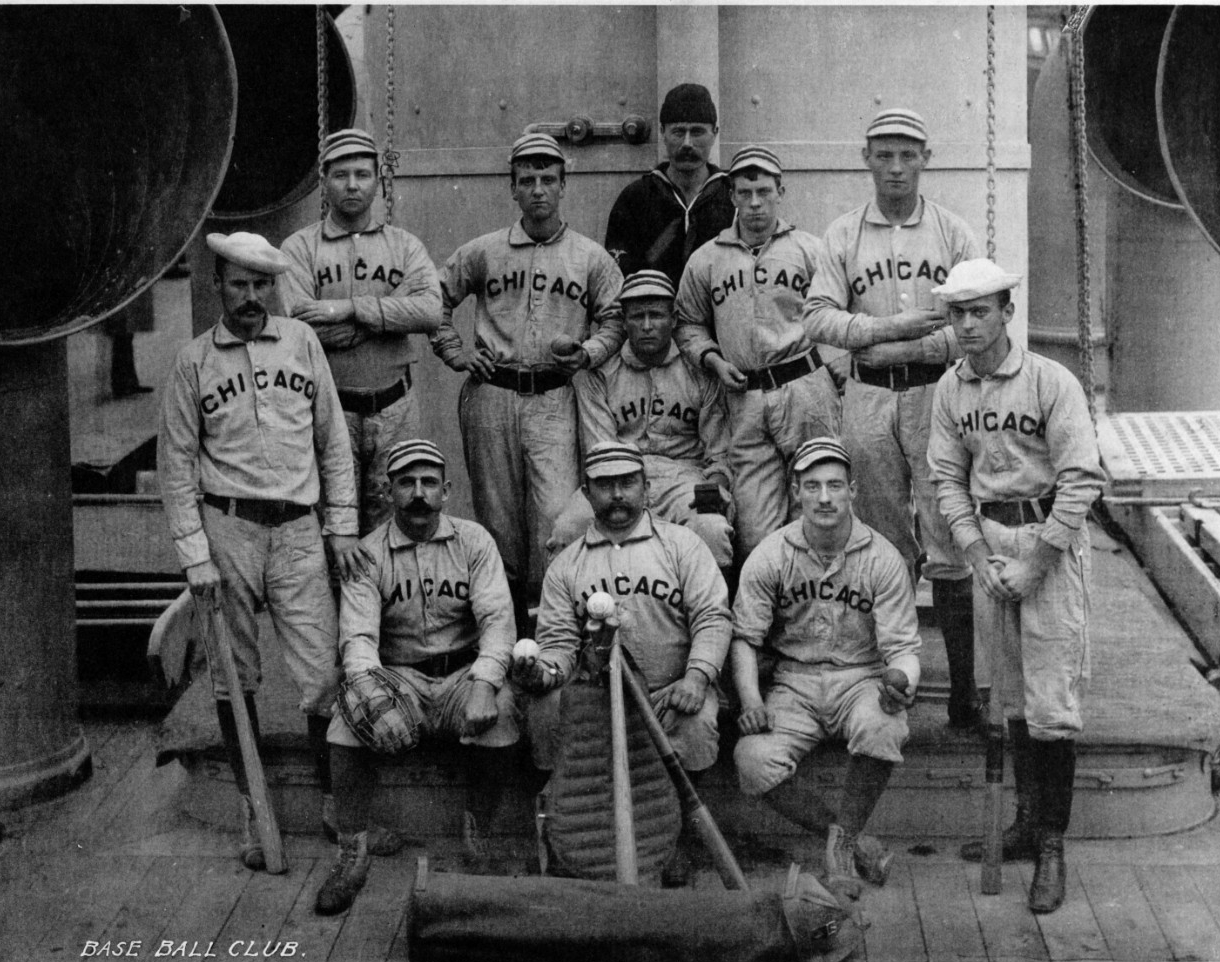

The Navy’s Role in “America’s Pastime”

As the weather gets warmer and fans return to the ballpark, there is always hope that this year could be the year your team takes home the World Series trophy. The crack of the bat, the smell of green grass, vendors selling beverages and snacks, fans singing “take me out to the ballgame” during the seventh inning stretch—nothing could be more classically American than baseball. In the nearly two centuries since baseball was created in America, the sport has expanded into a massively popular game that draws talent from all over the world. Its worldwide draw is in part due to the U.S. Navy. As Sailors traveled the world, so did the sport. Navy ships were known to visit Japanese ports and play against local teams as early as the 1870s. Sailors have also been credited with introducing the sport to such places as China, the Caribbean, Hawaii, Nicaragua, and the Philippines. By the beginning of the 20th century, baseball had become integral to training Sailors. It provided physical fitness training, and it also boosted morale and productivity.

The U.S. entry into World War I brought an influx of collegiate and professional players into the military. When not performing wartime duties, some Sailors found time to play the game in foreign ports. In fact, Navy baseball had become so popular that installations and ships formed several teams that competed in their own leagues. In Southeast Asia in 1916, teams from ships stationed from the Philippines to Shanghai gathered for a championship series that drew a crowd of more than 30,000. Many Asians watched U.S. Sailors play and picked the game up that way. More than 440 major and minor league players served during World War I.

When the United States entered World War II, professional players were not exempt from military service. However, not all the service branches were onboard with organized athletics during the war. For example, the Army curtailed sports, so many of the nation’s top players joined the Navy and Marine Corps. More than 500 Major League Baseball players and thousands of minor leaguers joined, including the likes of Bob Feller, a chief petty officer and gun captain, who enlisted the day after the Pearl Harbor attack; Ted Williams, who served as a naval aviator in both World War II and the Korean War; and Yogi Berra, a gunner’s mate and participant in the D-Day landings. Whether they volunteered or not, many of them played in exhibition games throughout the war to boost morale, raise funds, and unify the troops. Sailors played whenever they could as well, whether a suitable diamond was available or not. Games were often played at sea on the decks of aircraft carriers.

After the war, things changed a bit, and baseball wasn’t as prevalent in the service. A few professional players served in the reserves during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, including Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe, New York Mets pitcher Nolan Ryan, and Philadelphia Phillies centerfielder Gary Maddox. Others built careers after their service. Al Bumbry, who served as a platoon leader in Vietnam and earned a Bronze Star with “V” device, was a standout centerfielder for the Baltimore Orioles when they captured the 1983 World Series title. Only about 50 Major League Baseball players served during the Vietnam War, and none of them were stars at that point in their career. According to the Society for American Baseball Research, 535 baseball players have lost their lives in military service—whether they were killed in action or died from wounds, illness, or accidents—since the Civil War. Twelve of them were Major League Baseball players.

Although service members can no longer serve and play professional baseball at the same time, baseball continues to be an important pastime for those serving overseas and here at home. From overseas battlefields to shore installations at home, Sailors still enjoy the friendly competition of the sport. Over the course of the years, baseball has gone from “America’s Pastime” to a globally cherished sport, and the world can thank the U.S. Navy, in part, for its worldwide popularity. For more on Navy athletics, visit NHHC’s website.

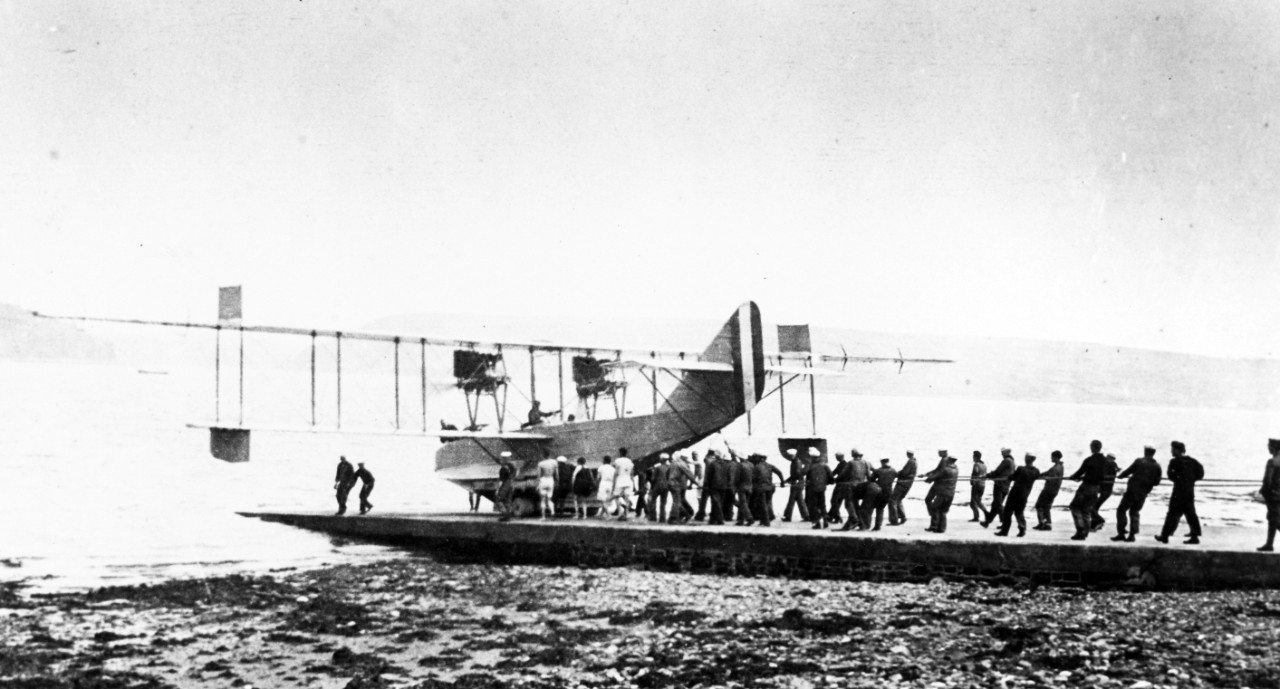

Today in Naval History—First Use of Jets as Bombers

On April 2, 1951, two F9F-2B Panther fighters of Fighter Squadron 191 (VF-191), each loaded with four 250- and two 100-pound general-purpose bombs, catapulted from USS Princeton (CV-37) to attack a railroad bridge near Songjin, North Korea. Their attack marked the Navy’s first recorded use of jet aircraft as bombers. Up to that point, Panthers provided fighter top cover and sometimes flak suppression (with guns and rockets) while AD-5 Skyraiders and F4U-4 Corsairs flew bombing missions. With little to no enemy air opposition during this period in the Korean War, Panthers were free to perform bombing runs as well. However, it was found that the hydraulic catapults on carriers at the time were not powerful enough to launch the heavier Panthers attached with large bombs in light- or no-wind conditions. Initially, it put a damper on the operation, but the U.S. Navy learned to overcome the obstacles.

The F9F Panther, the first jet-powered fighter operated by the U.S. Navy, was the primary jet fighter and ground-attack aircraft during the Korean War. Developed during the final months of World War II, Grumman designed the single-engine, straight-winged fighter that was armed with four 20 mm cannons and could also carry a wide assortment of air-to-ground munitions. On Nov. 21, 1947, a prototype Panther performed its first flight powered by an imported Rolls Royce engine. In September 1949, the Panther was cleared for flight from aircraft carriers.

On July 3, 1950, an F9F-3 Panther scored the first U.S. Navy air victory of the war by shooting down a propeller-powered Yak-9 enemy aircraft. The first Soviet MiG-15 was shot down by a Panther on Nov. 9, 1950, during a UN Command attack on the Sinuiju bridges, near the mouth of the Yalu River. About two weeks later, two more MiG-15s were shot down by Panthers. Collectively, Panther pilots were credited with shooting down seven MiG-15s during the Korean War. It was the most used Navy jet fighter of the conflict, cumulatively flying more than 78,000 sorties. A total of 1,385 Panthers were delivered to the Navy. Future astronauts Neil Armstrong and John Glenn flew the F9F extensively during the war. Future Major League Baseball hall of famer Ted Williams did as well.

During 1956, the Panther was withdrawn from frontline combat service, but it remained active in secondary roles. Until 1958, the Panther was used for training with U.S. Naval and Marine Air Reserve units. The Navy’s Blue Angels used the Panther for four years, beginning in 1951. The Panther was the Blue Angels first jet aircraft. Some Panthers continued to be used in small numbers into the 1960s. The successor to the Panther was the F9F Cougar. For more naval aviation firsts, visit NHHC’s website.