Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Battle of Midway

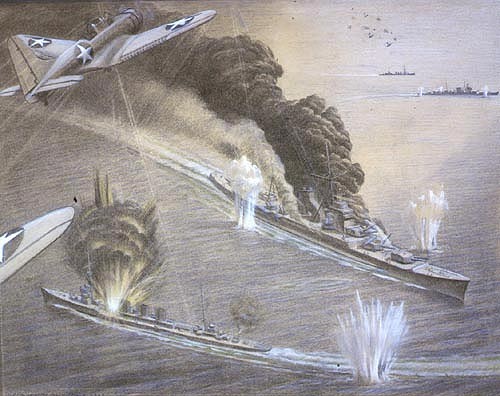

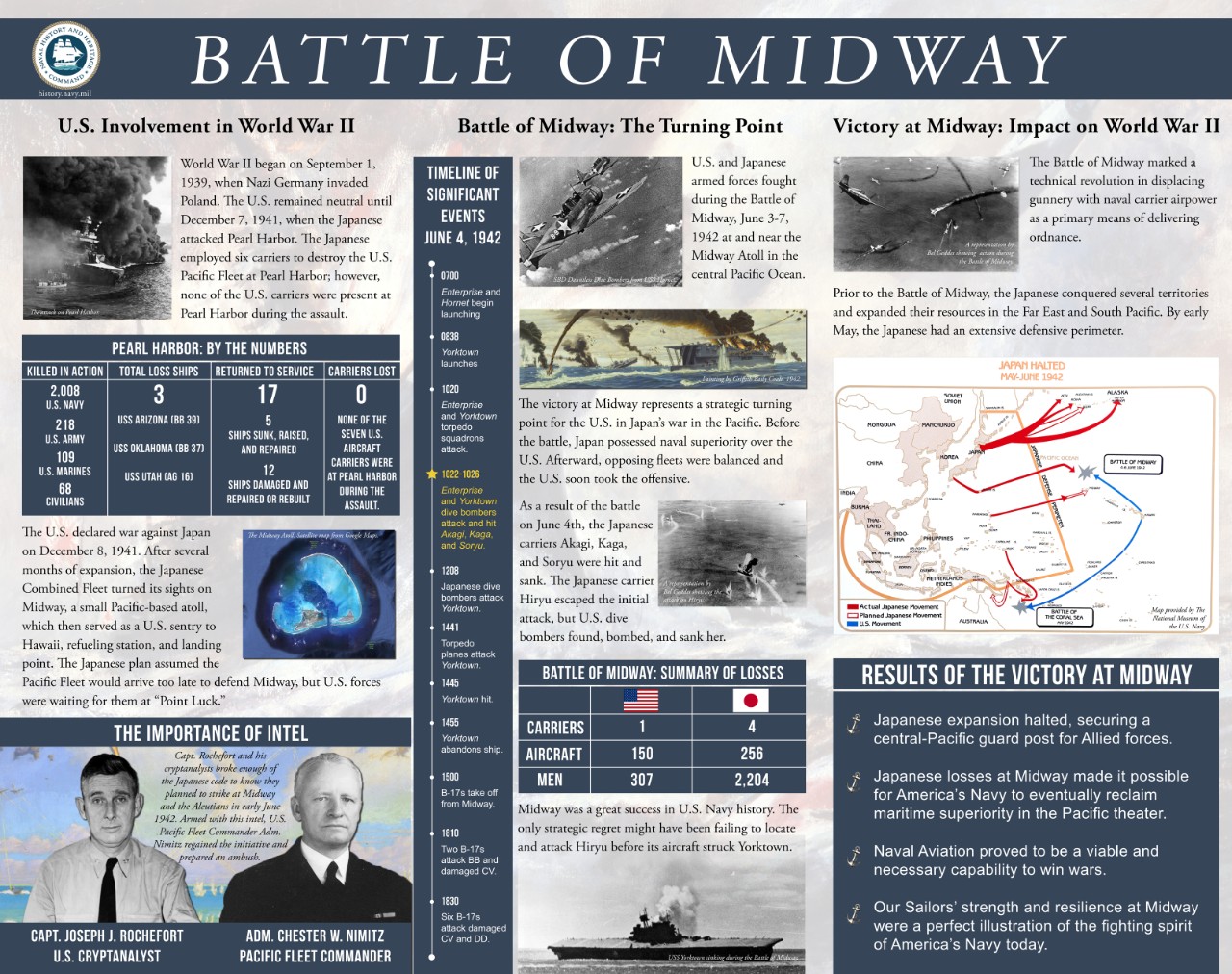

On June 4, 1942, the pivotal Battle of Midway began. That morning—after launching aircraft to attack the U.S. base at Midway—Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were mortally damaged by dive bombers from USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Yorktown (CV-5). However, later in the day, Yorktown was lost after taking multiple bomb and torpedo strikes by aircraft from Hiryu. That Japanese carrier, in turn, was knocked out of the fight by U.S. carrier planes. Devastated by their losses, the Japanese retired westward. The battle was a decisive victory for the U.S. Navy, bringing an end to Japanese naval superiority in the Pacific and turning the tide of the war.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ subsequent entry into World War II, the Japanese mounted attacks on U.S., British, and Dutch territories in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. The first phase of the Japanese offensive was the seizure of Malaysia, Singapore, Dutch East Indies, Philippines, and various island groups in the central and western Pacific. The second phase was to isolate and neutralize Australia and India. In the Pacific, the Japanese planned to seize bases in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, which would then be used to support future operations against New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. By March 1942, with the seizure of Lae and Salamaua, the entire north coast of New Guinea had fallen into Japanese hands. At the time, U.S. radio-intercept units were in operation, with one in Australia and the other at Pearl Harbor). These facilities intercepted Japanese radio communications and, through analysis and codebreaking, uncovered the location of major Japanese fleet units and shore-based air forces. More importantly, by translating messages and studying operational patterns, the radio-intercept units were able to predict future Japanese operations with some degree of certainty. The units provided their analysis, through daily briefings and warning reports, to senior commanders. On March 13, American cryptanalysts were able to identify the Japanese code designation “AF” as Midway.

In the meantime, after several months of debate, Adm. Isoruku Yamamoto had convinced Japanese leadership to agree to his Midway and Aleutians plan. The centerpiece was a diversionary operation toward the Aleutians followed by the invasion of Midway. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was expected to respond to the landings on Midway; however, Japanese carrier and battleship task forces were to be waiting undetected to the west of the island. They would fall upon and destroy the unsuspecting Americans. If successful, the U.S. Pacific Fleet would be effectively eliminated for at least a year. On May 5, Japan issued “Navy Order No. 18,” which directed Yamamoto, in cooperation with the Japanese army, to occupy Midway and key points in the western Aleutians.

On May 26, the Japanese Northern Force headed toward the Aleutians, and the next day, a Japanese force consisting of four large carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, with a total of 229 embarked aircraft, steamed for Midway. Two days later, elements of the Japanese First Fleet departed home waters while elements of Second Fleet, including 15 transports, steamed from Saipan. Meanwhile, Rear Adm. Raymond Spruance’s Task Force Sixteen (TF-16)—formed around Enterprise and USS Hornet (CV-8)—departed Pearl Harbor on May 28 to take up a position northeast of Midway. Two days later, Task Force Seventeen (TF-17), under the command of Rear Adm. Frank Fletcher, formed around Yorktown and steamed from Pearl Harbor to join TF-16 northeast of Midway. When TF-17 and TF-16 converged about 350 miles northeast of Midway on June 2, Fletcher commanded the combined force. The three U.S. carriers, augmented by cruiser-launched floatplanes, provided 234 aircraft afloat. These were supported by 110 fighters, bombers, and patrol planes at Midway. As part of the pre-battle disposition, 25 U.S. fleet submarines were deployed around Midway.

Just after midnight on June 4, U.S. Pacific Fleet the task forces on the course and speed of the Japanese main body. Shortly after dawn, a patrol plane spotted two Japanese carriers and their escorts, reporting, “Many planes heading to Midway from 320 degrees, distance 150 miles!” Later that morning, at roughly 6:30 a.m., Japanese carrier aircraft bombed Midway installations. Although U.S. Marine Corps fighters defending the island suffered heavy losses, the Japanese inflicted little damage to the island’s facilities. Between 9:30 and 10:30 a.m., torpedo bombers from the three American aircraft carriers attacked the Japanese carriers. Although these were nearly wiped out by the defending Japanese fighters and antiaircraft fire, U.S. fighters drew off enemy aircraft, leaving the skies wide open for dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown. Aircraft from Enterprise bombed and fatally damaged carriers Kaga and Akagi, while aircraft from Yorktown bombed and wrecked carrier Soryu. At approximately 11:00 a.m., Hiryu, the one Japanese carrier that escaped destruction that morning, launched dive bombers that temporarily disabled Yorktown. Three and a half hours later, Hiryu's torpedo planes struck a second blow, forcing Yorktown's abandonment. That afternoon, aircraft from Enterprise mortally damaged Hiryu. The destruction of the Japanese force compelled Yamamoto to abandon his Midway invasion plans and the Japanese fleet began to retreat westward.

Due to American intelligence capabilities, analysis, aircraft carrier tactics, and a lot of luck, the U.S. Navy inflicted a devastating defeat on the Imperial Japanese Navy. Although the performance of the three American carrier air groups would later be considered uneven, their pilots and crews had won the day through courage, determination, and heroic sacrifice. The U.S. Navy had lost a carrier, but the Japanese had lost four—all of which had participated in the Pearl Harbor attack. More importantly, the Japanese had lost more than 100 trained pilots, who could not be replaced. In a larger strategic sense, the Japanese offensive in the Pacific was derailed and their plans to advance on New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa postponed. The balance of sea power in the Pacific had begun to shift in favor of the Allies.

Normandy Landings

At first light, on June 6, 1944, nearly 7,000 U.S. and British ships and craft carrying about 160,000 troops lay off the beaches of Normandy, France, in anticipation of the largest amphibious landing in history. The massive assault, known as Operation Overlord, surprised the Germans, who had overestimated poor weather conditions and were also expecting the Allies to attack the Pas-de-Calais area to the northeast. After assembly and a 24-hour weather delay, the fleet made way across the English Channel toward the French coast. In passages cleared by minesweepers, it proceeded to assigned landing beaches—U.S. (Utah, Omaha) and British-Canadian (Gold, Juno, Sword). Initially, cruisers and destroyers bombarded enemy coastal fortifications and strongpoints, followed by tactical air strikes. In each of the attack waves, LCTs (landing craft, tank) carried specially configured amphibious tanks that supported the infantry once ashore. Patrol boats served as control vessels off each of the beaches, and destroyers and other small combatants stood by to provide gunfire support. Despite their success, some 4,000 Allied troops were killed in action by German soldiers defending the beaches. However, within a few days, about 360,000 troops, more than 50,000 vehicles, and 100,000 tons of equipment had landed. Within two weeks, Paris was liberated by the French 2nd Armored Division and the U.S. 4th Infantry Division after four years of German occupation. By the end of August, the Allies had reached the Seine River, and the Germans had retreated from northwestern France, effectively concluding the Normandy operation. At this stage, the Allied forces began preparing to enter Germany. The success of the Normandy invasion was a significant psychological and material blow to the Germans, although it did not spell the end of the war in Europe. It was not until the following spring, on May 8, 1945, that the Allies were to accept an unconditional surrender of Germany.

Operation Neptune, the naval component of Operation Overlord, played a vital role in spearheading the assault during and after the landings. U.S. Navy ships started one of the most famous days in history by bombarding the beaches of Omaha and Utah. A newly created Navy demolition unit removed obstacles alongside Army combat engineers early in the invasion. At one point in the historic battle, several destroyers positioned themselves as close to the shore as possible to fire point-blank at German fortifications. The action by the destroyers helped Allied troops who were pinned down by enemy fire and allowed them to move forward and engage the enemy. During the night before the Allied forces had stormed the beaches, hundreds of airplanes had filled the skies over northern France, dropping paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne and 101st Airborne Divisions as well as from the British 6th Airborne Division. Although many of the paratroopers missed their assigned drop zones, the errors actually helped the Allies because they sparked confusion in the German high command, convincing them that the airborne force was much larger than it actually was at the time.

For their part, the Germans suffered from confusion and the absence of their celebrated leader, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, who was on leave at the time. At first, Hitler believed the Normandy landing was a diversion to distract the Germans from an actual attack that was to take place north of the Seine River. He refused to release nearby divisions to counterattack the Allies, and initially resisted in deploying reserved armored divisions to help in the defense. In addition, the Germans were hampered by effective Allied air support, which took out many lines of communication, forcing German reinforcements to take long detours.

The successful invasion of northern France was one of the major events in U.S. Navy history. Rear Adm. Alan G. Kirk, in reflection, said, “Our greatest asset was the resourcefulness of the American Sailor.” The crews on board the destroyers also received accolades from many high-ranking officers within the Allied command for coming to the aid of troops on the ground just as the situation appeared dire. Major Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, who established V Corps headquarters on Omaha Beach, summed up the sentiment in a message to Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of U.S. First Army: “Thank God for the United States Navy!”

First African American Naval Academy Graduate

On June 3, 1949, after four years of education, Midshipman Wesley A. Brown became the first African American to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy. U.S. military academies had long struggled with racial tensions, and integration attempts after the Civil War had been largely unsuccessful. When Brown applied to the U.S. Naval Academy—which, by that time, had been in existence for 100 years—it had admitted a total of five African American students. None had graduated. At the academy, Brown faced an organized campaign of discrimination and harassment. Hostile midshipmen whispered racial slurs, refused to sit near him, spread false rumors, prevented him from joining the academy’s choir, and baselessly assigned him so many demerits that he was nearly expelled. He had to room alone for the entire four years at the academy. Brown credited his success at the academy with taking one day at a time, his special friendship with future President Jimmy Carter (a fellow teammate from the track team), and other supportive senior classmates. He noted that keeping a sense of humor was important as well. Conditions also somewhat improved for Brown when President Harry S. Truman formally ordered the desegregation of the Armed Forces in 1948.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on April 3, 1927, Brown came from a family of modest means, as his father delivered groceries for a living and his mother worked at a dry cleaning facility. He was the great-grandson of Virginia slaves. Brown grew up in a row house in Washington, DC, and when he was attending Dunbar High School, which was at the time segregated, he worked part-time jobs for the Army Reserve and Howard University. After he graduated from high school in 1944, he applied to the U.S. Naval Academy and was accepted the following year.

After he was commissioned, Brown served the Navy for 20 years as a civil engineer before his retirement in 1969. During his time in the Navy, he was initially assigned to temporary duty at the Boston Naval Shipyard before completing his postgraduate degree in civil engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1951. As an officer in the Civil Engineer Corps, he worked in Bayonne, New Jersey; Davisville, Rhode Island; and at the public works department at the Barbers Point Naval Air Station in Hawaii.

Some of his most noteworthy projects involved helping to design a water treatment facility in Cuba, leading a project building roads across Liberia with the Seabees, engineering an air station in the Philippines (where he also played a large role in the construction of the new aircraft carrier pier in Subic Bay), and providing input for the design of a nuclear plant in Antarctica. After retirement, Brown worked for the State University of New York, and from 1976 through 1988 his career came full circle when he served as the facilities planner for Howard University in Washington, DC, where he had worked as a teenager.

On March 25, 2006, the U.S. Naval Academy broke ground on a $50 million, 140,000-square-foot state-of-the-art indoor track facility. The academy had decided to name the field house to honor Brown’s impact on the Naval Academy. Two years later, the Wesley A. Brown Field House opened. In his remarks at the dedication of the facility, Brown said the naming of the new building symbolized the Navy's commitment to diversity.

Brown passed away on May 22, 2012, of metastatic cancer. He was 85 years old.

Today in Naval History

On May 30, 1998, 25 years ago, USS Pearl Harbor (LSD-52) was commissioned in San Diego, California. The Harpers Ferry–class dock landing ship is named after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that took the lives of more than 2,400 American service members and civilians and thrust the United States into World War II. During its maiden deployment, in January 2000, Pearl Harbor steamed with the USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) amphibious ready group, participating in Operation Southern Watch and exercises Eager Mace, Eastern Maverick, and Sea Soldier. Pearl Harbor returned to its homeport of Naval Station San Diego in July.

In the wake of the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks, Pearl Harbor deployed again with Bonhomme Richard in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, which struck Taliban and al Qaeda targets in Afghanistan in the initial phases of the war. In January 2003, Pearl Harbor provided support for operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. On Oct. 8, 2005, a devastating 7.2 magnitude earthquake struck in the Kashmir region of Pakistan, killing at least 79,000 people and collapsing more than 32,000 buildings. In response, Pearl Harbor deployed in a multinational humanitarian assistance and support effort. Pearl Harbor loaded equipment and supplies at Manana, Bahrain, on Oct. 14, and off-loaded the cargo in Karachi, Pakistan, four days later. Afterward, Pearl Harbor returned to the Persian Gulf, where it had been deployed to since July, and resumed maritime security operations. In December 2006, the ship steamed to Naval Station Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, to participate in the 65th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, honoring those who had fought and lost their lives on Dec. 7, 1941. Pearl Harbor has continued to honor veterans of the attack throughout the years with multiple Hawaiian port visits.

From 2008 to present day, Pearl Harbor—besides an overhaul from 2014–2016—has been in a continuous cycle of exercises, maritime security operations, humanitarian relief, and commemoration ceremonies. Although the ship briefly provided support for Operation Inherent Resolve in July 2017, and supported the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan (2020–2021). At this time, Pearl Harbor is slated to be decommissioned in 2024 and placed in the Reserve Fleet.