Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On May 3, 1975, USS Nimitz (CVN-68) was commissioned at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia. “Only America can make a machine like this,” noted President Gerald R. Ford at her commissioning ceremony. “There is nothing like her in the world.” The supercarrier is 1,092 feet in length and can accommodate a crew of 428 officers and more than 4,000 crewmembers. She is capable of supporting 85–100 aircraft. The ship, first in class, is named to honor Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who as commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, lead American forces to victory over the Japanese Empire during World War II. He was one of only four flag officers to attain the rank of five-star fleet admiral and served as Chief of Naval Operations after the war (1945–47).

After Nimitz was commissioned, she deployed to the Mediterranean twice in 1976 and 1977. On Sept. 10, 1979, she was dispatched to the Indian Ocean as tensions heightened when Iran took 52 Americans hostage at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. Four months later, Operation Evening Light was launched from Nimitz in an attempt to rescue the hostages. However, the rescue attempt was aborted in the Iranian desert when the number of operational helicopters fell below the minimum needed to complete the rescue.

In October 1988, Nimitz began operating in the North Arabian Sea in support of Operation Earnest Will, and in February 1991, relieved USS Ranger (CV-61) in support of Operation Desert Storm. Two years later, she returned to the Arabian Gulf as part of Operation Southern Watch. On Sept. 1, 1997, Nimitz set course for an around-the-world cruise, where she again was called upon to support Operation Southern Watch and various United Nations initiatives. In 2003, 2005, 2009, and 2013, Nimitz deployed in support of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom.

Nimitz, whose homeport is now Naval Base Kitsap, Bremerton, Washington, is the oldest American aircraft carrier in active service.

First of the Six Original Frigates Launched 225 Years Ago

On May 10, 1797, the first of the six original frigates, United States, was launched from Philadelphia, where she was built. Later that year, both Constellation and Constitution were also launched, respectively at Baltimore and Boston. Congress and Chesapeake were ready by 1799 (both launched at Portsmouth, New Hampshire), President by 1800 (New York). The frigates were built as a result of “An act to provide a naval armament” that was approved by Congress and signed into law by President George Washington. It established the U.S. Navy.

Once the American Revolution concluded, the Continental Navy was slowly dispersed, with the last American warship, Alliance, sold on Aug. 1, 1785. However, danger on the high seas persisted. Before the American colonies gained their independence from Great Britain, American merchant shipping depended heavily on the protection of the British Royal Navy. This was no longer the case. In the Mediterranean, Barbary pirates seized American vessels and tried to ransom the passengers and crew. The French Revolution commenced in 1789 and France and Britain entered into a renewed conflict. American merchant ships were now the subject of accusations by both countries that American shipping was not maintaining their nation's official neutrality stance since they continued trading with each of the warring countries. As the war raged on, the British blocked American ships from the French West Indies and also harassed American vessels as part of a wider effort to choke the economy of France. For several years, lawmakers debated on the issue of funding a new American navy.

Confrontations with Barbary pirates only got worse. The Barbary States signed a truce with Portugal and agreed to refrain from attacking British vessels in return for hefty payments. Then, they began to attack American ships not only in the Mediterranean, but also in the Atlantic off the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. On Jan. 2, 1794, the Third Congress of the United States resolved to create “a naval force, adequate to the protection of the United States against the Algerine corsairs.” A committee was formed, and it ultimately recommended that a fleet of six frigates be constructed.

The fate of the six original frigates varied, but most were relatively successful. United States was ordered to sea in the spring of 1798 and enjoyed immediate victories when she captured two French vessels near Barbados on her very first voyage. During the War of 1812, United States forced British frigate HMS Macedonian to surrender after the ships exchanged fire on Oct. 25, 1812. In 1861, during the Civil War, United States was captured by the Confederate navy and renamed CSS United States. United States was ultimately sunk in the Elizabeth River to form an obstruction against Union vessels. Constellation also enjoyed success early by capturing multiple French privateers. During America’s second war with Great Britain, she was effectively blockaded at Hampton Roads, Virginia, by the British fleet, but her presence helped protect fortifications at Craney Island. Constellation later enjoyed a colorful and wide-ranging career as she protected American shipping and battled pirates. During the 1840s, she circumnavigated the globe. Constellation was broken up in 1853.

Initially serving as flagship in the Mediterranean, President cruised off the eastern coast of the United States from 1809–1812, where she took 11 merchant ships and the British navy schooner High Flyer. After she returned to New York in February 1814, she spent the next year blockaded by the British. President attempted to escape, but was captured off the coast of New York by British ships Endymion, Majestic, Pomone, and Tenedos. Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr., who was commanding officer of the ship at the time, was made prisoner and taken to Bermuda, along with his crew. The Royal Navy took the American frigate into service as HMS President until she was broken up in 1817 at Portsmouth, England. Chesapeake was also ultimately captured by the British during the War of 1812, but had early success in the blockade of Tripoli.

In 1804, Congress joined the Mediterranean Squadron, and for an extended period, protected American merchant ships. When war broke out with England, Congress made several brief cruises along the U.S. East Coast before she was assigned to the squadron patrolling the North Atlantic from June–August 1812. On her second patrol, in company with President, the frigates captured nine prizes and had multiple encounters with British ships before returning to the United States at the end of the year. On April 30, 1813, Congress set sail again cruising off the Cape Verde Islands and the Brazilian coast, where she captured four small enemy ships. In 1820, Congress became the first U.S. Navy ship to visit China at Canton (Guanhzhou). In 1834, she was found unfit for repairs and was broken up.

Constitution, however, enjoyed unparalleled success throughout her career. Constitution's crew defeated four British frigates during three separate engagements during the War of 1812. In battle, Constitution earned the nickname “Old Ironsides” because it appeared as if enemy cannonballs could not penetrate the ship's strong oak hull. Notably, Constitution—homeported at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston—remains and is the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat and the world’s oldest sailing vessel still capable of sailing under its own power.

For more on the U.S. Navy’s Six Original Frigates, visit NHHC’s website. It contains a short history on each of the frigates, suggested reading, selected imagery, and much more.

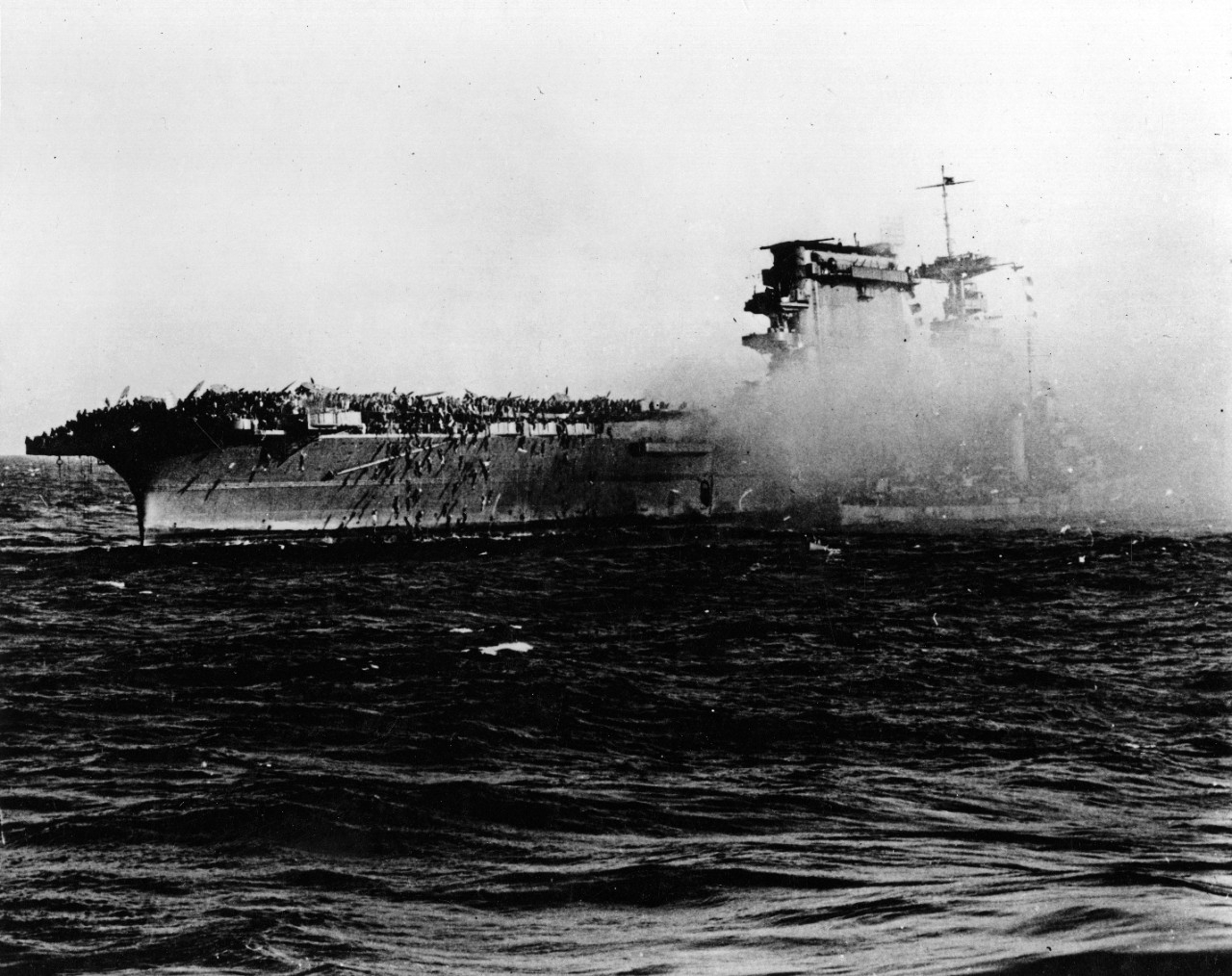

WWII@80: Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first time since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that the enemy’s seemingly relentless advance into the Pacific was tested. It was also the first major U.S. Navy fleet action against the Japanese Empire and the first naval engagement in history in which the participating ships never sighted or fired directly at each other. From April 29–May 4, Japanese forces successfully attacked, invaded, and occupied Tulagi in the Solomon Islands, although USS Yorktown (CV-5) sank or damaged several of their warships with her naval aviation assets. Alerted to the presence of U.S. aircraft carriers in the vicinity, the Japanese carrier strike force advanced toward the Coral Sea with the intention of finding and destroying Allied naval forces. Beginning on May 7, the two sides exchanged air strikes over two consecutive days. The clash of two U.S. Navy task forces and a combined U.S. and Australian cruiser force with the Japanese armada resulted in a tactical victory for the Japanese with the sinking of USS Lexington (CV-2), USS Sims (DD-409), and USS Neosho (AO-23). Yorktown was also heavily damaged. The Japanese lost only one small carrier, Shoho, and suffered damage to a fleet carrier, Shokaku. Moreover, the Allies were forced to withdraw from the area. However, the Japanese air groups were too battered to support a further advance, and the Japanese forces were brought to a standstill. Although the Japanese did capture Tulagi, Port Moresby remained in Allied control. Shokaku was damaged so severely that she could not join the planned Midway action scheduled for the following month. Also, due to the losses of pilots and aircraft, another Japanese carrier, Zuikaku, was not able to join the Midway force. The Coral Sea action reduced Japanese carriers available for Midway by a third and saved the fragile lifeline between America and Australia.

Although the Battle of the Coral Sea was the first setback for the Japanese, American cryptanalysts had broken the Japanese navy’s general purpose code months earlier. They tentatively identified “AF” as Midway—the next tactical Japanese occupation. The damage Yorktown suffered during the battle was estimated to take about three months for the overhaul. Unfortunately, due to to the cryptanalysts’ findings, there was little time for repairs. As Admiral Chester W. Nimitz began to plan for the upcoming battle, which included Yorktown, yard workers at Pearl Harbor miraculously labored around the clock and made enough repairs to enable the ship to be put to sea. On May 30, Yorktown steamed to Midway as the central ship of Task Force 17. On June 4, the Battle of Midway, which ultimately turned the tide of the war in the Pacific, commenced.

V-E Day

On May 8, 1945, both the United States and Great Britain celebrated Victory in Europe (V-E) Day. Cities in both countries, as well as formally occupied cities in Western Europe, rejoiced in the defeat of the Nazi war machine. It was the day that German troops throughout Europe finally laid down their arms, ending six years of unprecedented bloodshed. Leading up to the surrender, in the spring of 1945, Germany’s situation was dire, and they appeared on the verge of defeat, but exactly when the Nazi leaders would admit so remained unknown. However, on April 30, 1945, in his command bunker in Berlin, the Führer, Adolf Hitler, who had touted a thousand- year Greater Germany, killed himself. Hitler’s mistress and a number of close followers also joined him in death. Before Hitler took his own life, he named Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, the commander in chief of the German Kriegsmarine (navy), as his successor.

Facing overwhelming odds, Doenitz’s main goal in the waning days of the war was to ensure maritime evacuation—from the Baltic provinces to western Germany—of as many German troops and civilians as possible before the last remaining German-held ports fell into the hands of the Soviets. On May 5, a day after German troops surrendered to the British army in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northwestern Germany, Doenitz contacted General Dwight D. Eisenhower in France to negotiate Germany’s surrender. From his headquarters in the northern German port city of Flensburg, Doenitz tried to draw out negotiations as long as possible in order to continue the withdrawal in the east, but Eisenhower would not tolerate the Germans stalling their inevitable surrender. On May 7, German armed forces chief of operations, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, signed the instrument of unconditional surrender in Rheims. The surrender ceremony was repeated the following day with the Soviets in Berlin by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel as the German signatory.

As during World War I, the U.S. Navy’s contribution to the war effort in the European theater of operations was significant. Its main mission was to ensure that a sufficient amount of personnel and material reached European and northern African shores. From early 1942 through May 1943, the Battle of the Atlantic had been a mixed success for the Allies. Enormous quantities of supplies helped sustain Great Britain and the Soviets, and a combined U.S.-Anglo force successfully completed an amphibious assault that secured North Africa between November 1942 and the spring of 1943.However, thousands of ships and millions of tons of supplies and raw materials were sent to the bottom of the ocean as German U-boats sank more shipping tonnage than the Americans and British could construct. Increasing industrial capacity, new technologies, intelligence, better training, and updated organizational approaches helped turn the tide of the European war. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King’s creation of Tenth Fleet, dedicated to antisubmarine warfare, also was a major contributor. In addition, air attacks on German infrastructure and the Allies’ recapture of French ports in 1944 further reduced the U-boat menace. In fact, during the first four months of 1945, Germany lost 153 submarines, compared to only 85 in all of 1942. However, U-boats remained a danger until the very end. Just before surrender, Germany made a last-ditch effort to to attack shipping off of the eastern coast of the United States. On the evening of May 5, German submarine U-853 sank American collier Black Point, just four miles from Block Island, Rhode Island. However, the enemy submarine failed to make it out quickly enough and was sunk several hours later.

At the time V-E Day had arrived, the war in the Pacific still raged on. Planners envisioned sending a steady flow of personnel from the European to the Pacific theater during the second half of 1945 to force a Japanese surrender in 1946. Some 400,000 Solders were projected to leave Europe and the Mediterranean, with most expected to arrive by late September. Another 800,000 were set to deploy from the United States. Fortunately, only about a third of them reached the Pacific. On Aug. 14, Emperor Michinomiya Hirohito announced to the Japanese people that Japan had agreed to surrender unconditionally. On Sept. 2, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. World War II was finally over.