Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On April 19, 1997, 25 years ago, USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) was commissioned at Staten Island, New York, under the command of Cmdr. Gerard D. Roncolato. The motto of the ship, honoring the five brothers, is “We Stick Together.” The Arleigh Burke–class destroyer is the second Navy ship named after the five Sullivan brothers, who were killed in action on Nov. 13, 1942, while serving aboard USS Juneau (CL-52). George and Francis Sullivan—the two oldest—enlisted in the U.S. Navy on May 11, 1937, and served on the destroyer USS Hovey (DD-208) into June 1941. At Des Moines, Iowa, Jan. 3, 1942, George and Francis, accompanied by their younger brothers Joseph, Madison, and Albert, reenlisted to avenge the loss of Seaman 1st Class William V. Ball, a friend, who was killed while serving on the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. After receiving initial training at the Naval Training School in Great Lakes, Illinois, all five brothers, at their expressed request, joined the light cruiser Juneau at the New York Navy Yard, Feb. 3, 1942.

Commissioned on Feb. 14, 1942, Juneau initially served in the Atlantic, but was transferred to the Pacific in August. Late in October, she took part in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and, on Nov. 12, fought in the fierce night battle off Guadalcanal. In that action, a torpedo severely damaged the ship. The following morning, the crippled cruiser, down by the bow and struggling to make 18 knots, retired from the battle area. Handling sluggishly as she limped through the glassy-calm sea, Juneau was an easy target for Japanese submarine I-26 nearby. A torpedo strike hit the damaged cruiser and detonated her magazines. The resulting explosion tore the ship apart, and she went down in just 42 seconds.

Four of the Sullivans, Coxswain Francis Sullivan and Seamen 2nd Class Joseph, Madison, and Abel, failed to make it topside in time to abandon their doomed ship. Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class George Sullivan, wounded during the Nov. 12 night action, managed to get over the side and pull himself onto a raft, but died of his wounds a few hours later. Only ten of approximately 140 were rescued from the ship.

The first ship named after the brothers, USS The Sullivans (DD-537), was commissioned on Sept. 30, 1943. Her sponsor was the boys’ mother, Alleta. The ship served in the U.S. Navy until she was decommissioned on Jan. 7, 1965. She is currently a memorial at the Buffalo and Erie County Naval and Servicemen's Park in New York. The current destroyer, The Sullivans, is still active and is homeported in Mayport, Florida.

Operations Persecution and Reckless

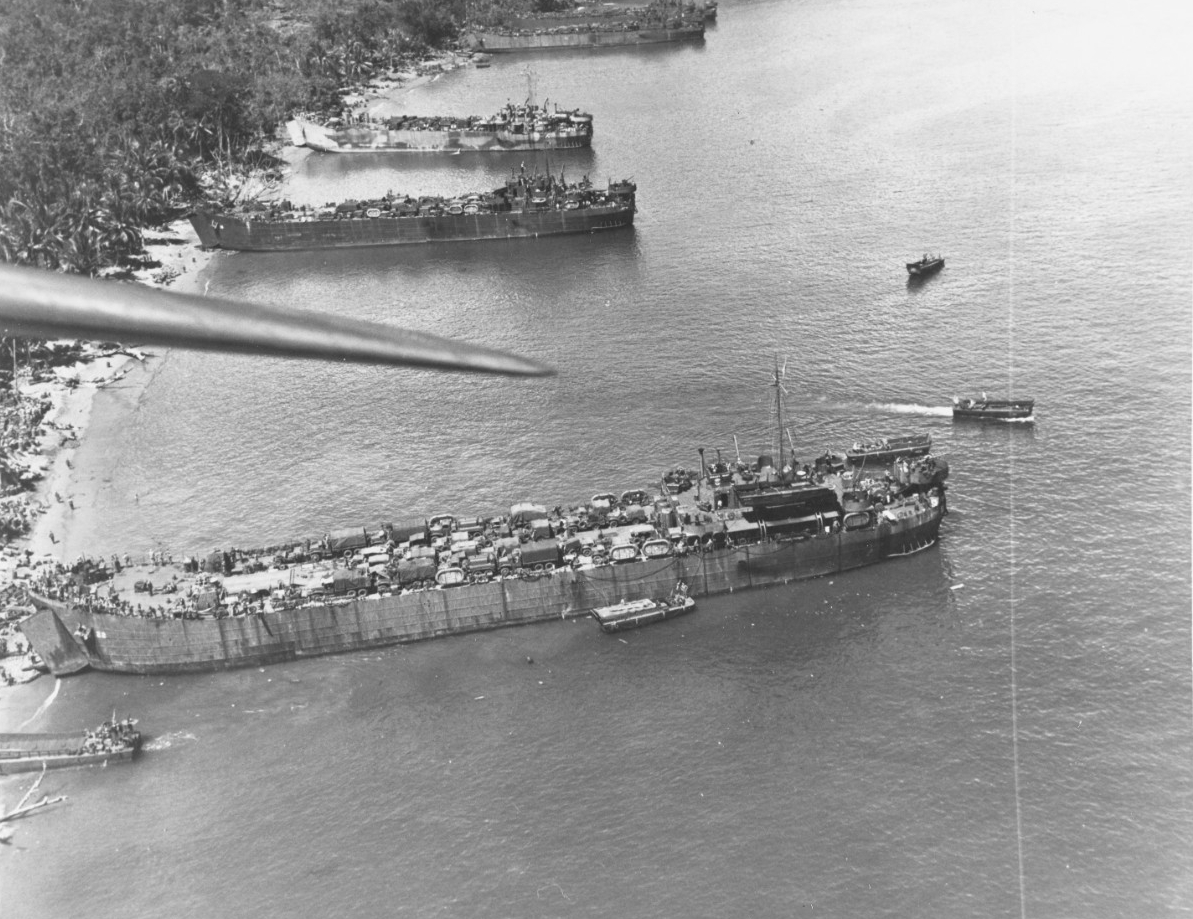

On April 21, 1944, Task Force 58 began bombing Japanese airfields and defensive positions at Hollandia, Wakde, Sawar, and Sarmi, New Guinea, in preparation for the landing of several U.S. Army divisions. The operations Reckless, which aimed for the conquest of Hollandia and nearby airfields, and Persecution, which focused on the landing strips near Aitape, aimed to secure northern New Guinea and would aid the Allied in their progress toward the Philippines and the Japanese home islands. The task force, which consisted mainly of Lexington (CV-16), Enterprise (CV-6), Langley (CVL-27), Bunker Hill (CV-17), Yorktown (CV-10), Monterey (CVL-26), and Cabot (CVL-28) provided air support for a variety of actions including raids on airfields (April 21), and the landings at Humboldt Bay and Tanahmerah Bay the following day. They also supported “boots on the ground” as the landing force moved inland. The operations lasted about six weeks.

The spring 1944 fight for northern New Guinea’s airfields was in part a product of the Casablanca Conference—the January 1943 meeting between President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and members of the French government-in-exile. At the conference, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to work together to attack Japan on multiple fronts in the Pacific and to take Japanese bases in New Guinea. This push would be part of a wider effort to weaken the Japanese in three ways: first, to divert their attention to the southwest Pacific in time for the Allies to strike in the north; second, to eliminate the Japanese southwest Pacific–area headquarters at Rabaul; and third, to reconquer the Philippines. The capture of the airfields gave the Allies the heavy-bomber bases necessary for General Douglas MacArthur’s push to the Philippines and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s progress toward the Marianas and Palau.

Once the area was secure, Army and Navy assets, with the help of Allied engineers, began to develop bases in and around Hollandia. Humboldt Bay was expanded into a naval advance base with supply and ammunition depots, ship repair facilities, and other support installations. Tanahmerah Bay was accommodated with a new fuel depot. These bases, as well as the airfields around nearby Lake Sentani, soon became an invaluable staging area for the Philippines Campaign of 1944–45.

Doolittle Raid

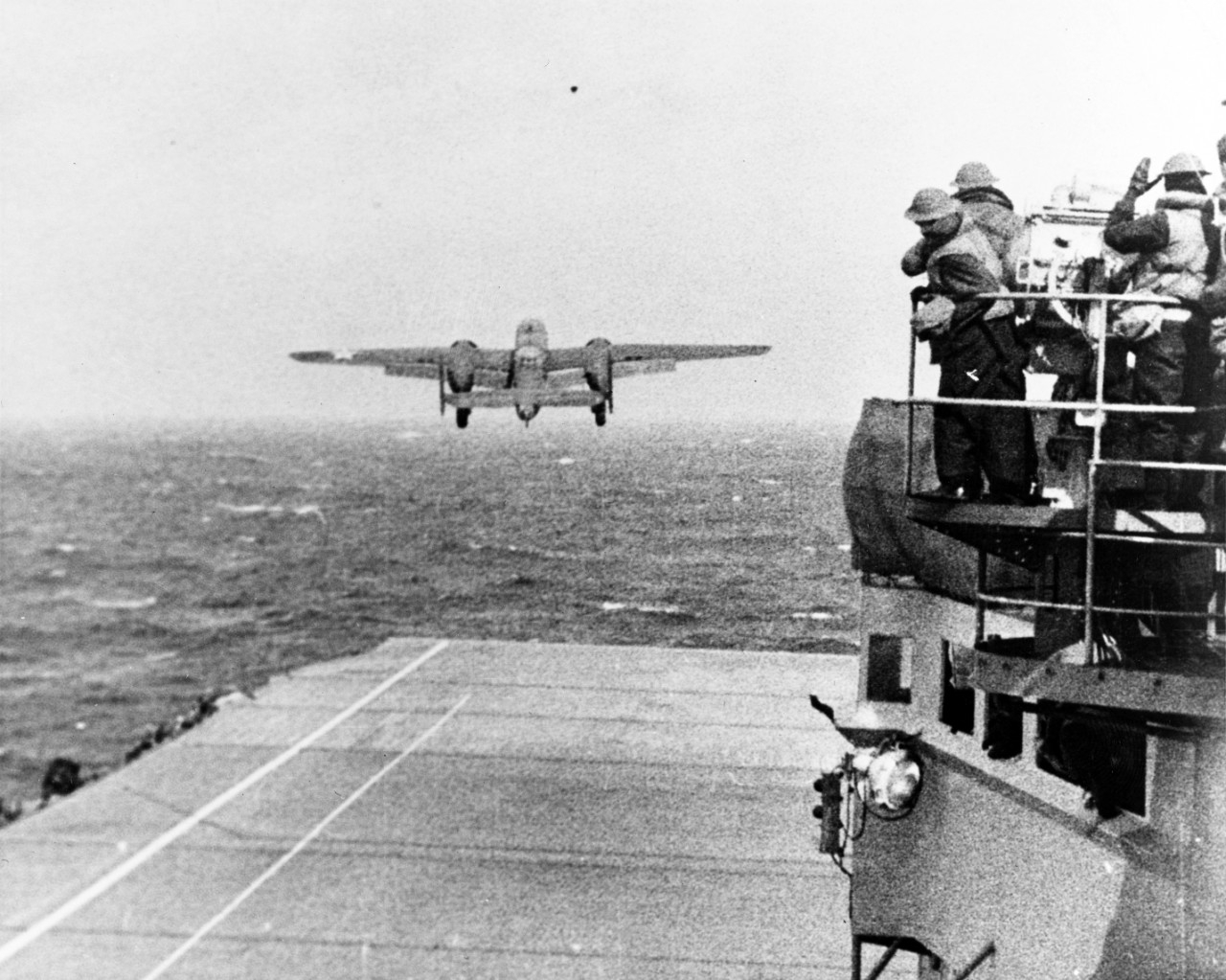

Conceived shortly after the deadly Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor attack that killed more than 2,000 Americans and propelled the United States into World War II, the “joint Army-Navy bombing project” was hatched to inflict “material and psychological” damage against the heart of the Japanese Empire. On April 18, 1942, led by U.S. Army Air Forces Lt. Col. James Doolittle, 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers launched from the aircraft carrier Hornet (CV-8) approximately 650 miles off Japan. Their mission was to attack the Japanese homeland and incite a “fear complex” on the Japanese people. After a longer than anticipated flight, Doolittle’s Raiders dropped high explosive and incendiary bombs on targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya. Originally, the plan was to launch and recover the aircraft much closer to Japan, but the task force was discovered earlier than expected by a Japanese picket boat. The early launch meant that the pilots, after making the bomb run, would have to land in occupied China and hope they wouldn’t be taken prisoner by the Japanese. Of the 16 B-25’s, 15 crashed in China and one landed intact at Vladivostok, where the Soviets interned it and its crew. Two of the crews were captured by Japanese forces after they bailed out, one near the Chinese coast and one near Lake Poyang. The Chinese attempted to purchase the freedom of the captured air crews, but they were unsuccessful. Four of the raiders remained prisoners of the Japanese until the end of the war. One, Lt. Robert J. Meder, died of dysentery in 1943. Three—Lt. Dean Hallmark, Lt. William Farrow, and Sgt. Harold Spatz—were executed by the Japanese in October 1942. Doolittle survived and later was promoted to brigadier general and awarded the Medal of Honor.

Although the attack did little material damage to Japan, the effect of the air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed “unreasonable” by the Naval General Staff, had occurred unimpeded. The Doolittle Raid dissolved the residual doubts harbored within the Japanese staff whether or not a thrust against the important U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out U.S. aircraft carriers, should be attempted. The reality of U.S. bombers over Tokyo skies forced them to accelerate the expansion of their strategic defensive perimeter. This would culminate in the planned invasion of the Midway Islands in the central Pacific. U.S. cryptanalysts had penetrated the Japanese JN25 naval code, however, and Pacific Fleet commander Adm. Chester Nimitz ordered his carriers to intercept the Japanese naval force. At the subsequent Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942), U.S. naval air power destroyed Japan’s first-line carrier strength and reversed the tide of the war in the Pacific.

After America’s resounding victory at Midway and with the Japanese navy reeling, the Japanese army carried out a terrifying campaign of reprisals against the Chinese. The second Sino-Japanese War had somewhat reached a stalemate in 1942, but the raid highlighted the threat posed by Nationalist-controlled territory along the Chinese coast. Within days of the raid, Japanese planners began formulating a campaign to neutralize the airfields and punish those who were deemed helpful to the Doolittle Raiders. In early June 1942, the Japanese launched an offensive into Chekiang and Kiangsi, and the brutality directed at the civilian population was unspeakable. Trinkets and souvenirs left by the Doolittle Raiders—parachutes, cigarettes, and other military gear—doomed entire villages, as the Japanese judged all the residents as being complicit. Japanese bombers devastated Chuchow and Kiangsi’s provincial capital of Nancheng. Entire populations were simply wiped out. It is estimated that some 250,000 civilians were killed during the reprisal campaign.

As for the raiders, Doolittle, in addition to the nation’s top honor, also received two Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, Bronze Star, four Air Medals, and decorations from Great Britain, France, Belgium, Poland, China, and Ecuador for his service during the war. He retired from active service with the Air Force in 1946 as a lieutenant general. He passed away in 1993 at the age of 96 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Lt. Col. Dick Cole, who served as Doolittle’s co-pilot, died in April 2019. He was the last living Doolittle Raider. In 2018, a museum commemorating the raid and celebrating the Chinese villagers who helped the American air crews opened in Chuchow (Quzhou).

Navy’s Role in the Popularity of Baseball

As the weather gets warmer and fans return to the ballpark this month, there is always hope that this year could be the year your team takes home the World Series trophy. The crack of the bat. The green grass. Vendors selling their snacks and libations. Singing during the seventh-inning stretch. Nothing could be more classically American than baseball. In the nearly two centuries since baseball was created in America, the sport has expanded into a massively popular game that draws talent from all over the world. A lot of that growth is thanks to the U.S. Navy. As Sailors traveled the world, so did the sport. Navy ships were known to visit Japanese ports and play against local teams as early as the 1870s. Sailors have also been credited with introducing the sport to places such as China, the Caribbean, Hawaii, Nicaragua, and the Philippines. By the beginning of the 20th century, baseball had become integral to training Sailors. It provided physical training, and it also boasted morale and productivity.

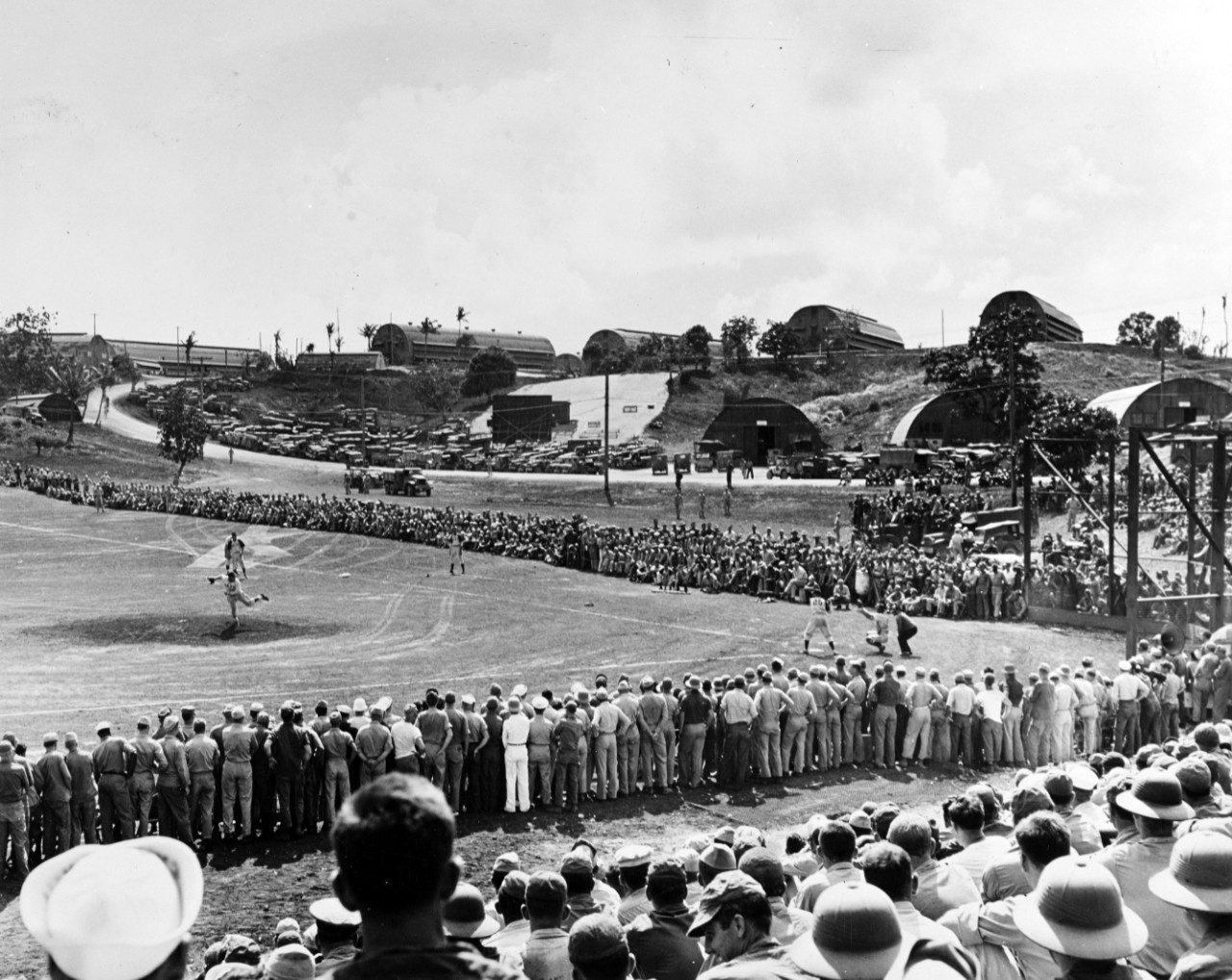

The U.S. entry into World War I brought an influx of collegiate and professional players into the military. When not performing wartime duties, some ships found time to play the game in foreign ports. In fact, Navy baseball had become so popular that installations and ships formed several teams that competed in their own leagues. In southeast Asia in 1916, teams from ships stationed from the Philippines to Shanghai gathered for a championship series that drew a crowd of more than 30,000. Many of the natives from the foreign countries watched Sailors play and picked the game up that way. More than 440 major and minor league players served during World War I.

When World War II broke out, professional players were not exempt from the service. However, not all the service branches were onboard with organized athletics during the war. For example, the Army curtailed sports, so many of the nation’s top players joined the Navy and Marine Corps. More than 500 Major League Baseball players and thousands of minor leaguers joined, including the likes of Bob Feller (a chief petty officer and gun captain), Ted Williams (a naval aviator in both World War II and the Korean War), and Yogi Berra (a gunner’s mate and participant in the D-Day landings). Whether they volunteered or not, many of them played in exhibition games throughout the war to boost morale, raise funds, and unify the troops. “During the greatest conflict in the history of the United States, baseball was there to provide both a distraction and a uniter,” said NHHC historian Gordon Calhoun. “America’s game went to war and sacrificed along with everybody else.” Sailors played whenever they could as well, whether a suitable diamond was available or not. Games were often played at sea on the decks of aircraft carriers.

After the war, things changed a bit, and baseball wasn’t as prevalent in the service. A few professional players served in the Army and the reserves during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, including Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe and New York Mets pitcher Nolan Ryan. Others built careers after their service. Al Bumbry, who served as a platoon leader in Vietnam and earned a Bronze Star with “V” device, was a standout center fielder for the Baltimore Orioles that captured the 1983 World Series title.

Although service members can no longer serve and play professional baseball at the same time, baseball continues to be an important pastime for those serving overseas and here at home. From the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan to shore installations, Sailors still enjoy the friendly competition of the sport. Over the course of the years, baseball has went from “national recreation” to a globally cherished sport, and the world can thank the U.S. Navy for that. For more on Navy athletics, visit NHHC’s website.