“The Action of 17 November 1917”

The Capture of SM U-58

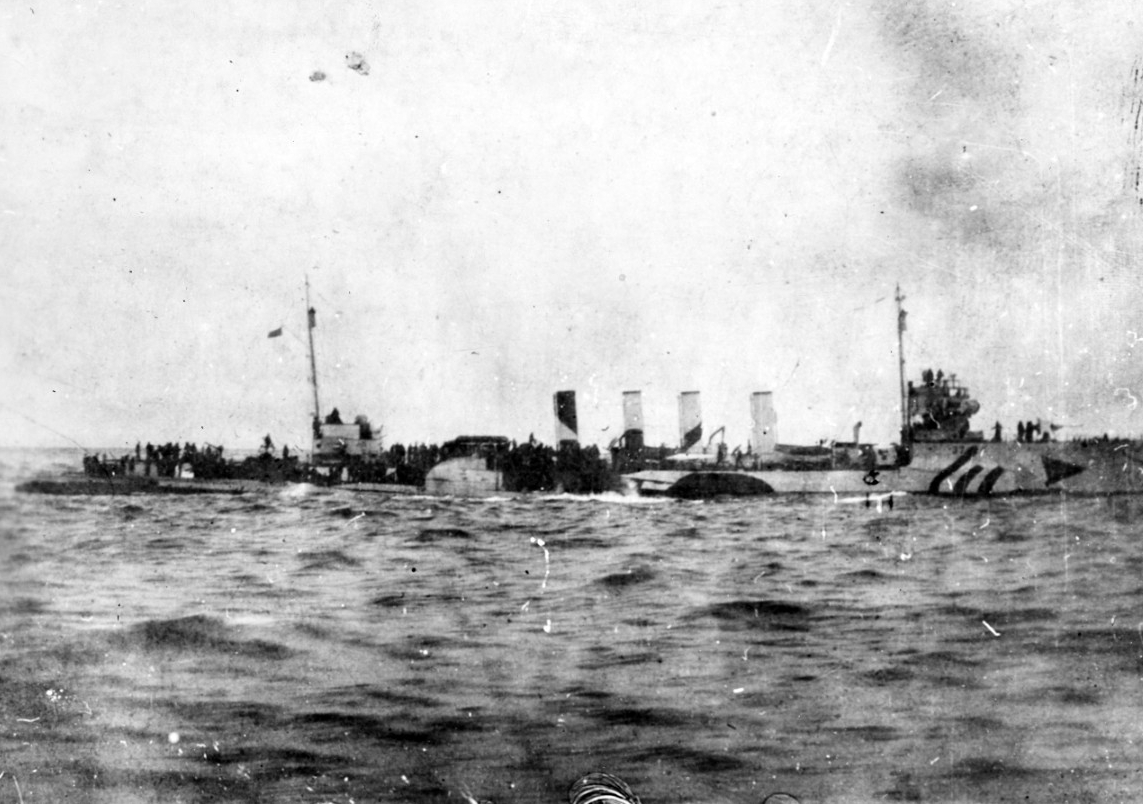

By November 1917, the United States and its Entente allies had settled into a bruising war of attrition with German submarine raiders. Entente shipping suffered record losses of tonnage to German submarines during the spring of 1917, peaking at over 875,000 tons that April.1 In response, the Entente, with the support of Commander of United States Forces in European Waters Vice Admiral William S. Sims, instituted an expanding convoy system that connected ports across the world. Anti-submarine warships escorted assembled shipping through dangerous waters and engaged any submarine raiders. The convoy system drastically lessened losses among Entente vessels and secured crucial shipping lanes. During this period, the 742-ton Paulding-class destroyer Fanning (Destroyer No. 37) escorted several convoys out of its base in Queenstown, Ireland. The smaller destroyer served alongside the generation of newer and larger “1,000-tonner” destroyers like the O’Brien–class Nicholson (Destroyer No. 52) and antisubmarine craft of other Entente nations. By November, the Americans had become experienced submarine hunters and were well acquainted with the primary anti-submarine weapon, the depth charge. The previous month, Fanning twice dropped depth charges on potential targets without visible effect. Fanning’s lack of substantive success was typical: No American warship had yet won a confirmed victory over a German U-boat.

At 1145 on 17 November 1917, the six American destroyers and two British corvettes that comprised the escort of convoy O.Q. 20, steamed out of Queenstown harbor under the command of the senior officer, Commander Frank D. Barrien, Nicholson's captain. Throughout the afternoon, the convoy’s eight merchant vessels fell in with the escort and set about forming into four columns arranged abreast. Fanning, under acting commander Lieutenant Arthur “Chips” Carpender, guarded the rear port flank of the convoy as O.Q. 20’s formation slowly took shape. At 1610, seven miles south of Queenstown, the convoy encountered SM U-58.2

U-58 was a U-57–type German submarine commissioned on 9 August 1916. Launched that 16 October as part of the Imperial German Navy's II Flotilla, the raider had already sunk 21 vessels in approximately one year of operation. By 17 November, only eight days into its first cruise under new commanding officer Kapitänleutnant Gustav Amberger, U-58 had already sent a British sailing vessel to the bottom.3 Amberger and his crew, however, were stalking larger prey. With prior knowledge of a convoy departing from Queenstown, the submarine waited in ambush beginning on the morning of 16 November.4 Sighting the convoy on 17 November, Amberger selected his target, the 5,782-ton steamship Welshman, and closed to attack.

The battle almost ended before it began. When the sound of propellers announced O.Q 20’s presence, the German commander ordered a torpedo prepared to fire and brought his boat to periscope depth. Soon after surfacing, poor visibility nearly led the submarine to ram Nicholson accidentally, and Amberger had the engines put full back to avert disaster. Nicholson continued, oblivious to the close encounter, and the submarine escaped unnoticed. After avoiding detection, U-58 again raised its periscope to reestablish contact with the target.5

Victory in “The Action of 17 November 1917” rested less on a sophisticated new technology or a brilliant tactical maneuver, and more on the eyes of Fanning’s Coxwain David D. Loomis, who was standing watch on the bridge. He was already renowned for his remarkable eyesight, with a Fanning officer later recalling Loomis’s possession of “a most extraordinary set of eyes.”6 In foggy conditions, Loomis spotted the 1.5-inch-diameter periscope protruding 10 inches out of the water at a distance of 400 yards away on the port bow. Although lookouts usually spotted submarine periscopes by the telltale wake they caused, U-58 was proceeding so slowly at the time of the sighting that it was not producing any noticeable disturbance in the water.7 After the eagle-eyed Loomis called out the periscope, officer-of-the-deck Lieutenant Walter O. Henry sounded General Quarters as he ordered the rudder hard left and rung up full speed.8 Through his periscope, Amberger suddenly saw a destroyer emerging from the mist, close aboard, and threatening to ram his boat. The U-boat skipper had no time to react before Fanning was upon him. On the destroyer’s bridge, Lieutenant Carpender, now on deck, ordered Fanning’s rudder right, swinging the ship into the submerged U-boat’s path before dropping a single depth charge off the fantail.9

U-58’s crew felt the shock of the exploding depth charge, which damaged the U-boat’s stern and disabled its electrical gear. Fanning’s depth charge exploded prematurely in the water, slightly damaging the destroyer as well. Amberger, underestimating the damage to his vessel, attempted to dive and elude his assailant. To his dismay, Fanning’s attack left U-58 unmanageable and leaking badly, with the diving gear, motors, and oil leads all wrecked. The U-boat dangerously sank to between approximately 150 and 250 feet, below its maximum diving depth, before Amberger blew the tanks and surfaced.10

On the surface, approximately 500 yards away, sailors aboard Nicholson witnessed Fanning’s attack and Commander Barrien turned his ship toward the spot of the explosion.11 As the destroyer completed its turn, U-58’s conning tower breached the surface. Nicholson rapidly closed and dropped a depth charge close aboard, scoring another hit on the submarine. The second explosion brought the U-58’s bow up rapidly before it righted itself.12 Fanning, having turned in Nicholson’s wake, again closed on the submarine. Gun crews on Fanning’s bow and Nicholson’s stern opened fire on the doomed U-boat.13 After three shots from both destroyers’ guns, the German sailors flung open U-58’s hatches and poured on deck, arms raised in surrender. The battle had lasted approximately 15 minutes.

After cautiously circling with their guns trained on the U-boat, Nicholson ordered Fanning to go alongside to pick up prisoners. Fanning approached and threw a line to U-58. As the destroyer prepared to take the submarine in tow, the boat began to sink rapidly. The Germans had opened the seacocks. The submarine crew quickly abandoned ship as the water rose above the deck. As they jumped overboard, several submariners became entangled in the boat’s radio antenna and were pulled deep below before freeing themselves. When Fanning threw lines to the men in the water, these sailors lacked the strength to pull themselves up. Although Fanning’s crew was able to pull most on board, one exhausted German, Chief Engineer Franz Glinder, sank below the surface. Fanning’s Chief Pharmacist Mate Elizer Harwell and Coxswain Francis G. Connor dove overboard into the frigid November North Atlantic and attached a line to distressed sailor. Although the crew pulled the German onboard, the Americans were unable to revive him. He was the only crewmember of U-58 to die in the engagement.14 After transferring the prisoners to Allied control at Queenstown, Carpender and his crew again departed the port onboard Fanning and buried Glinder at sea with full honors.15 The Americans treated their captives with kindness and respect, and, as the prisoners disembarked from Fanning, they gave the ship three cheers for their treatment.16

Fanning’s victory was celebrated by the Allies. On 19 November 1917, the Royal Navy’s Commander-in-Chief of the Coast of Ireland, Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, came onboard and read a congratulatory cablegram from the British Admiralty addressed to the ship. Also visiting the ship was the chief of staff of the U.S. Destroyer Flotilla Operating in European Waters, Captain Joel Pringle, the ranking American officer at Queenstown. Pringle read similar congratulatory cables from Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William Benson and Vice Admiral Sims. The Navy awarded Commander Barrien and Lieutenant Carpender the Distinguished Service Medal, and Coxswain Loomis and Lieutenant Walter O. Henry the Navy Cross. Chief Pharmacist Mate Elizer Harwell and Coxswain Francis G. Connor received written commendations. Perhaps the greatest honor of all came when Vice Admiral Bayly granted the crew permission to paint a coveted star on its front funnel to proclaim a confirmed victory over a U-boat.

Few other American vessels would paint a star on their funnel. Confirmed American victories over U-boats were few in World War I, and Fanning and Nicholson’s victory was a rarity. Like Fanning and Nicholson, however, American destroyers and antisubmarine craft stood guard over crucial convoys for the remainder of the war. Their tireless watch forced submarine commanders to remain below the surface, at a distance, and prepared to flee lest they suffer the same fate as U-58. Much like “The Action of 17 November 1917,” convoy escorts and their active and diligent crewmembers proved decisive in the war against the U-boat.

—S. Matthew Cheser, NHHC Histories and Archives Division, November 2017

__________

1 William Still, Crisis at Sea (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2006), 337.

2 Summary of War Diary Fanning; Entry 520, Subject File, 1911–1927; Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Record Group (RG) 45, National Archives Building (hereafter NARA I) Washington, DC.

3 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender, “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M. U-58, 17 November, 1917,” 18 November, 1917, Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I. “Ships Hit by U 58.” U-Boat Net: https://uboat.net/wwi/boats/successes/u58.html; accessed 3 October 2017.

4 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender, “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M. U-58, 17 November, 1917,” 18 November, 1917, Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

5 Captain William Poinsett Pringle, “Report Relative German Prisoners received on board from U.S.S. FANNING,” 24 November, 1917, Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

6 R. B. Carney, "The Capture of the U-58." U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 60, No. 10 (October 1934): 1401.

7 Lieutenant G. H. Fort, “Report of noteworthy incidents which came to my notice during engagement with and destruction of enemy submarine U-58, at 4:20 p.m., 17 Nov. 1917,” 18 November, 1917, Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

8 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender, “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M., U-58, 17 November, 1917” 18 November, 1917, Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

9 “Summary of War Diary Fanning;” Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I, “German Officers—Prisoners—on board U. S. S. DIXIE.” Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I. Vice Admiral William Sims, “Engagement with and Destruction of German Submarine U 58 on 17 November 1917,” 23 November 1916, Entry 520, RG 45 NARA I.

10 “Summary of War Diary Fanning;” Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

11 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender, “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M., U-58, 17 November, 1917” 18 November, 1917; Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

13 “Summary of War Diary Fanning;” Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.

15 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M. U-58, 17 November, 1917” 18 November, 1917; Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I. Other sources claim that two sailors from U-58 died. This is entirely possible, but American sources in the weeks following the battle do not mention a second sailor dying in the battle. In two articles in Proceedings from the 1930s, both written by officers on Fanning, mention a second German sailor missing from U-58. Former Fanning officer Commander George Fort recalled a sailor was seen to dive off the submarine and was not seen again. Lieutenant Carpender claimed that this sailor likely was picked up by Nicholson. Available sources are unclear whether Nicholson did, in fact, pick up the sailor and if he was truly missing. George Fort, "Discussion." U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 61, No. 1 (January 1935): 92; "Discussion," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 61, No. 1 (January 1935): 92; R. B. Carney, "The Capture of the U-58," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 60, No. 10 (October 1934): 1401.

16 Lieutenant Arthur Carpender, “Engagement with, and Destruction of German Submarine S.M. U-58, 17 November, 1917,” 18 November, 1917; Entry 520, RG 45, NARA I.