Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command Communication and Outreach Division

World Cruise of Great White Fleet Remains Relevant Today

Recently, Naval History and Heritage Command published a short booklet, “A Pacific Effect:” The United States Navy, Naval Engagement, and the World Cruise of the Great White Fleet. Sponsored by and with contributed input from Plans, Policy, and Integration (N5), Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, NHHC historians Daniel P.M. Curzon and Tyler A. Pitrof analyze the 1907–09 world cruise of the Great White Fleet and provide worthwhile lessons using historical context to support current operational planning. Although the famed circumnavigation of the globe by 16 steam-powered, steel-hulled battleships from the U.S. Atlantic Fleet occurred more than a century ago, lessons learned from the unparalleled cruise remain relevant today.

"For the relatively green American Navy, the journey provided valuable experience in logistical planning, diplomatic presence operations and engagement, and deliberate operational planning of the most pressing naval warfare tasks. President Theodore Roosevelt used the fleet’s passage to show our nation’s maritime power and to send a global message of friendship,” says Rear Adm. Thomas Moninger, director of N5, in the booklet’s forward. “While over a century has passed since the Great White Fleet returned from this unique operation, there is much to learn from it. Today, the Navy still operates forward to secure our nation’s interests and to provide a foundation for the international rules-based order that has helped so many nations to prosper.”

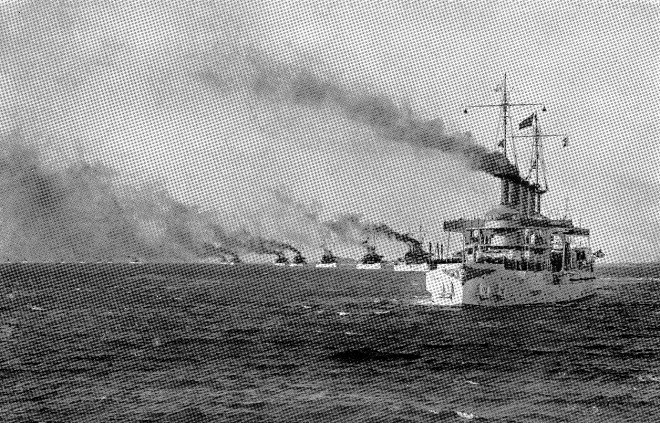

On a warm, cloudy morning on Dec. 16, 1907, President Roosevelt’s battleship force, bristling with guns and painted sparkling white, departed Hampton Roads, Virginia, to begin what would become a 43,000-mile, 14-month circumnavigation of the globe. The four-mile-long armada’s world tour included 20 port calls on six continents. Fourteen thousand Sailors and Marines participated in the three-leg voyage, leaving a lasting legacy at home and abroad. It was widely considered one of the greatest peacetime achievements of the U.S. Navy, and it made President Roosevelt’s message clear: “America is a respected world power, with a strong Navy leading the way.”

The world cruise of the Great White Fleet was a diplomatic victory. Besides demonstrating that the United States could project power globally, it improved relations with many countries, notably Australia and Japan. The cruise also fulfilled Roosevelt’s expectation that the Great White Fleet would help educate the American public about naval operations and stimulate widespread support for the U.S. Navy. Moreover, it provided Navy personnel with practical experience in sea duty and ship handling, leading to improved formation steaming, fuel economy, and morale. It invigorated a national commitment to naval power and inspired the United States to have a Navy second to none.

In “A Pacific Effect,” the authors encourage present-day officers and officials to consider their current situation from a new perspective that offers potential insights. In this pursuit, the booklet is organized into seven chapters, each analyzing a specific aspect of the world cruise in connection with present-day concerns. Chapter 1 establishes the basic geopolitical environment of the early 20th century, placing the world cruise in the context of American foreign policy and international relations. Chapter 2 then investigates the state of the Navy in 1908 through an analysis of the development of its fleet, officer corps, and doctrinal thinking. Next, Chapter 3 follows on this by examining the role that the U.S. Navy played in American foreign policy in a multipolar world. How established activities like “show the flag” visits combined with events and the evolution of the naval attaché system to generate the idea of the world cruise is the subject of Chapter 4, while Chapter 5 examines how this concept was then aligned with doctrine to make it a reality, a process which demonstrated the many shortcomings of the early 20th century Navy as a learning institution. Chapter 6 then examines the actual engagement activities of the Navy while the cruise was underway, which included an ad hoc response to a devastating earthquake in the Strait of Messina in December 1908. Finally, Chapter 7 concludes by examining how the Navy both succeeded and failed to learn from the world cruise, and suggests some instructive lessons for the present day.

To download a 508-compliant PDF version of this informative booklet, visit NHHC’s website. It’s free, as are all other NHHC publications posted to our website.

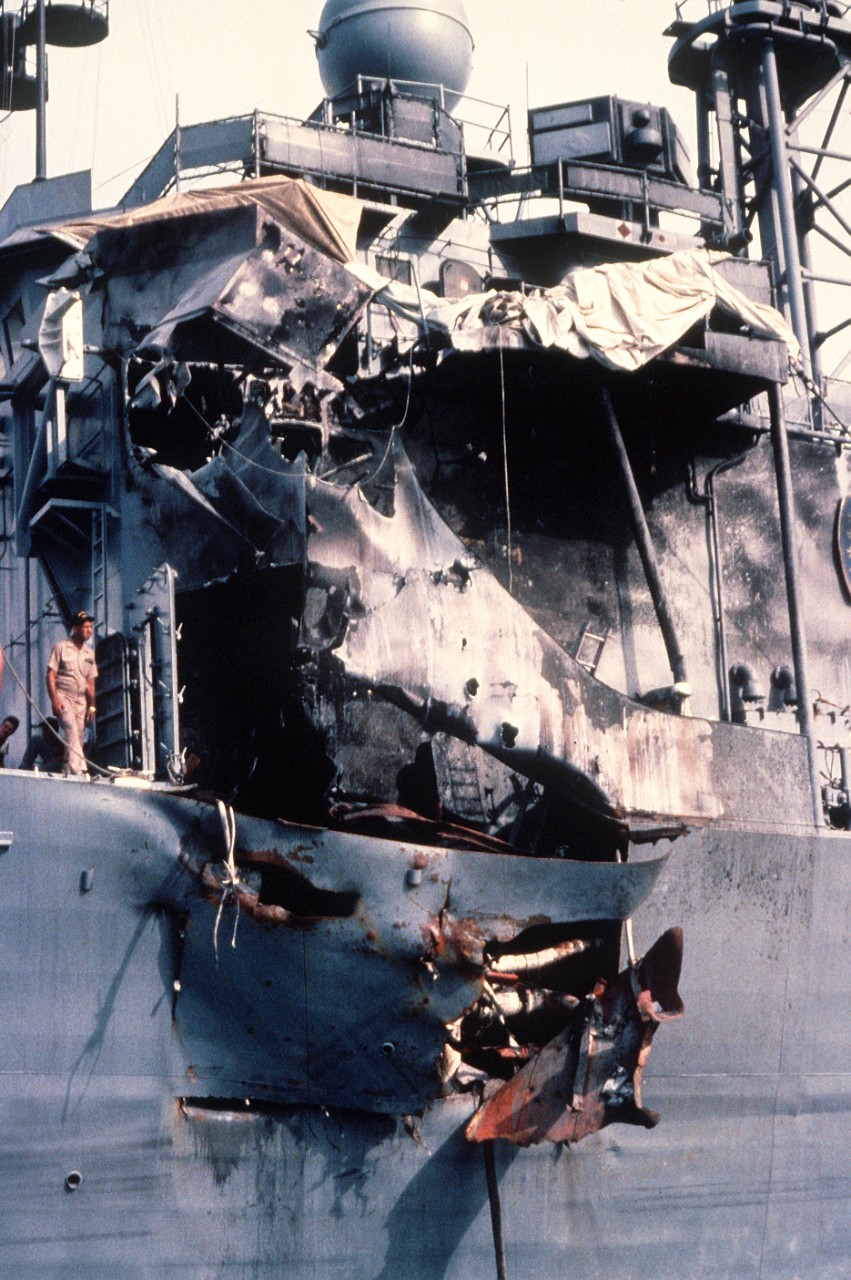

On May 17, 1987, USS Stark (FFG-31), while on patrol in the Persian Gulf, was struck by two Iraqi launched Exocet air-to-ground missiles, which killed 37 crewmembers and wounded another 21. It was the deadliest attack on a U.S. Navy ship since the Vietnam War. Stark was off the Saudi Arabian coast near the Iran-Iraq War exclusion boundary when it was hit. The first missile slammed into the port side of the ship, nearly 13 feet above the waterline, but did not detonate. It severed the firefighting water lines to the forward part of the ship and caused volatile fuel to leak. About 25 seconds later, a second missile hit a few feet aft of the same location and exploded, with the fuel from the first missile feeding the detonation of the second. The shock of the hits tore fixtures from bulkheads and wrecked equipment. Heat from the fires and blinding smoke initially impeded damage-control efforts, and flames melted the aluminum superstructure and decks.

Lt. William A. Conklin, the ship’s damage control assistant at the time, had just completed a long day of watches and was settled into his rack for some much-anticipated rest when the first missile struck. Conklin leaped to his feet and quickly donned his coveralls as the bridge transmitted an alarming order over the intercom: “Inbound missile, port side, all hands brace for shock.” The second Exocet missile struck the ship, and the lieutenant raced to his battle station in Damage Control Central, where he learned to his dismay that the attacks had all but neutralized the firefighting system. The blaze reached extreme temperatures and threatened the ship, so Conklin and Hull Maintenance Technician 1st Class Michael J. O’Keefe crawled through the fire despite agonizing pain from the heat and closed the critical fire main valves, isolating the torn pipes. “It was a fight for survival,” O’Keefe later said. “I was fighting to stay alive.” The blaze engulfed berthing spaces, the ship’s store, post office, and barber shop. Crewmembers used a portable P-250 pump to provide water to battle the flames in the forward section of the ship, supplementing their efforts with electric submersible pumps. Sailors felt heat rising from the deck into their feet, but continued to direct water onto the flames, only to discover that the heat turned the water into scalding steam. The crew sprayed so much water onto the ship that it listed up to 17 degrees to port from the weight.

The attack also severed some of the ship’s communications, so the firefighters rigged a “salt and pepper” line with sound-powered phones between the bridge, aft steering, and the flight deck in order to direct damage-control efforts. Crewmembers also threw missiles and .50-caliber rounds overboard to prevent them from exploding. The crew used so many oxygen breathing apparatus canisters that they ran out, which brought their firefighting efforts to a standstill. USS Waddell (DDG-24) and other ships in the vicinity brought them additional canisters within the hour. Firefighting teams from other ships also rotated through, relieving Stark’s exhausted crewmembers. The thick black smoke blocked emergency lighting and plunged compartments below deck into total darkness, but the crew used flood lanterns to illuminate some of the darkened compartments and passageways. In addition, live electrical wires torn from their housings burned some members of the crew. The attack destroyed the ladder ascending to the upper decks, and as some of the crew ran out of air, they had to choose between the raging fires or jumping in the sea. Some jumped out of the very hole torn by the impact of the missile strikes. A lookout tossed them life rings as Stark moved on. They survived until the next morning despite recollections of spotting sharks.

Eventually, Stark’s crew and other personnel from the ships in the vicinity saved the ship. Iraq, which at the time was a U.S. ally, subsequently apologized for the attack. They claimed the pilot involved mistook Stark for an Iranian tanker. The attack incensed many Americans, and Sixth Fleet alerted USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63)—already deployed to the Mediterranean—to stay in the area for possible retaliatory strikes against the Iraqis, but the carrier eventually moved on. “I know and I share,” President Ronald Reagan said the next day, “the sense of concern and anger that Americans feel over yesterday’s tragedy in the Persian Gulf…. The officers and crew of USS Stark deserve our highest admiration and appreciation.” Stark returned home to Naval Station Mayport, Florida, to a hero’s welcome. Stark returned to service in August 1988.

McCann’s Rescue Chamber Saved 33 Lives

On May 24–25, 1939, Vice Adm. Allan R. McCann’s rescue chamber became the first deep-water device that was used to save crewmembers on a sunken submarine. On May 23, 1939, USS Squalus (SS-192) flooded and sank off Portsmouth, New Hampshire, after a main engine air-induction valve was left open. Twenty-six of its crew, trapped in the flooded aft compartments, drowned. However, 33 managed to survive in the forward part of the submarine. Lt. Cmdr. Charles Momsen, the initial designer of the chamber, led the rescue effort during four submersions to retrieve all the survivors successfully from a depth of 243 feet. Four Navy divers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic actions during the rescue.

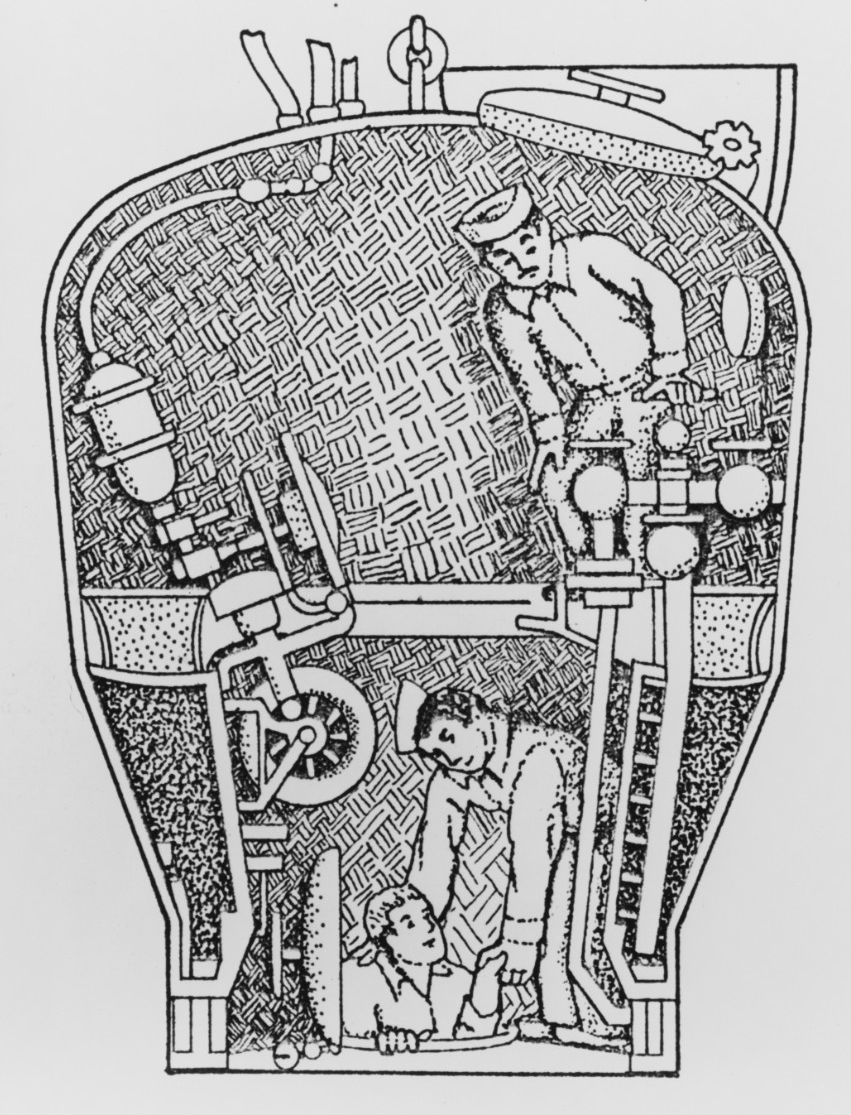

Under Momsen’s direction, the Bureau of Construction and Repair had begun developing the rescue chamber in 1928. After extensive testing and experimenting, Momsen was reassigned within the bureau to design an underwater breathing apparatus for submarine escape—which became known as the Momsen lung, his most famous invention. The bureau placed then–Lt. Cmdr. McCann in charge of the design revisions Momsen had planned for the rescue chamber. McCann directed the development of the chamber for a year and a half; once completed in 1930, the bell was introduced by the Navy as the McCann rescue chamber. The chamber worked by coupling with a submarine’s escape hatch. The lower compartment of the chamber was cleared of water by blowing it into the chamber’s ballast tanks. Once the pressurized air in the lower chamber was released into the upper compartment and vented to the surface, the chamber and submarine are at equal pressure. The submarine’s escape hatch could be opened, and the trapped submariners could enter the rescue chamber for transport to the surface.

The loss of USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963 and USS Scorpion (SSN-589) in 1968 in extremely deep water—without the possibility of rescue—triggered the Navy to completely rethink submarine design, maintenance, and operations to reduce the number of unrecoverable submarine accidents. This would lead to the Submarine Safety Program, an ongoing quality-assurance effort by Sailors and contractors to ensure the safety of the submarine fleet, covering everything from welds to operating procedures. For decades, the Navy has invested in developing and maintaining the ability to locate and rescue crews of downed submarines. Today, the Undersea Rescue Command (URC) is home to the Navy’s submarine rescue specialists. URC provides operational, administrative, maintenance, and logistical oversight of the Navy's shallow and deepwater rescue systems as well as the remotely operated vehicle intervention system. URC uses a combination of active duty Sailors, Reserve personnel, and government contractors to provide worldwide submarine rescue coverage for United States and foreign submarines. URC is the sole U.S. provider for submarine rescues for the Navy.

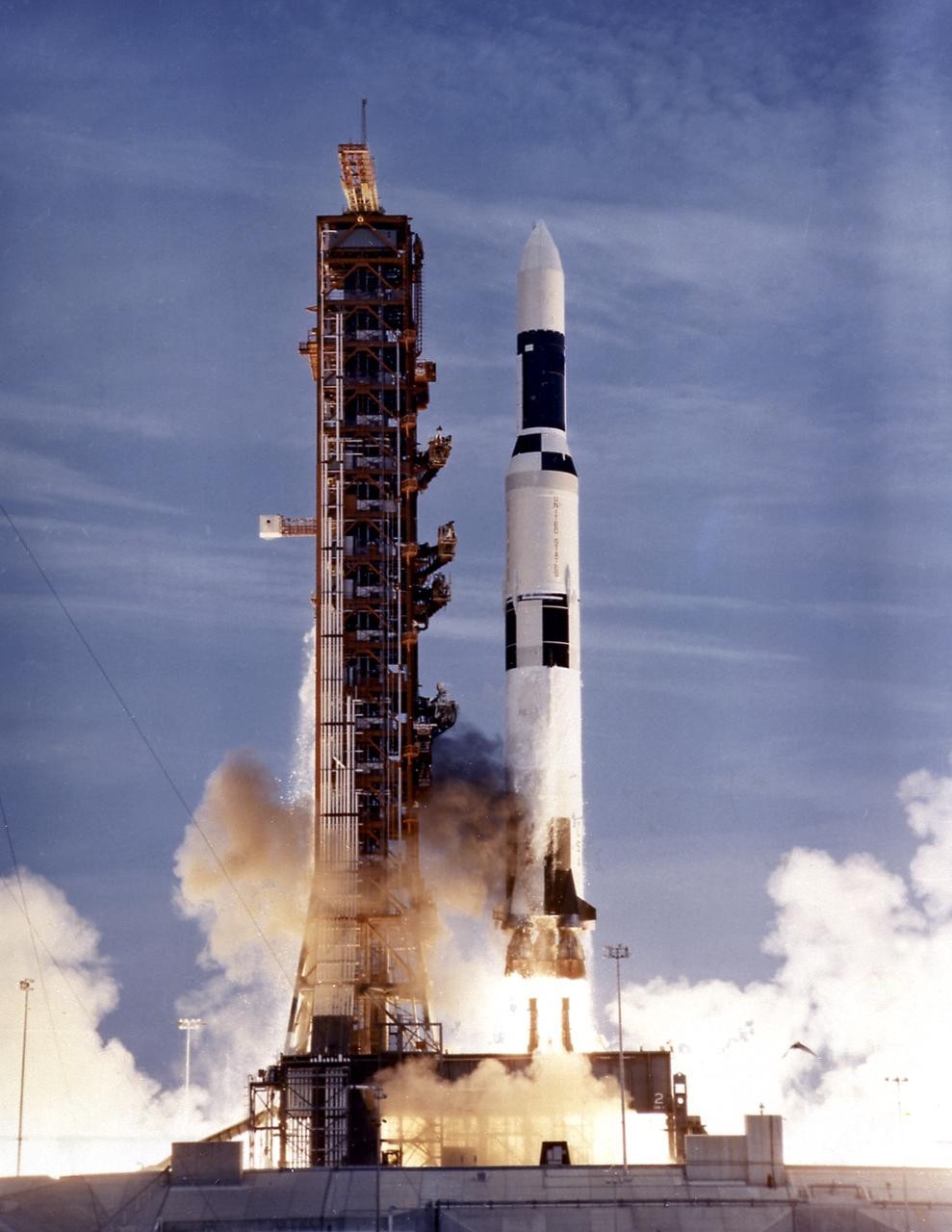

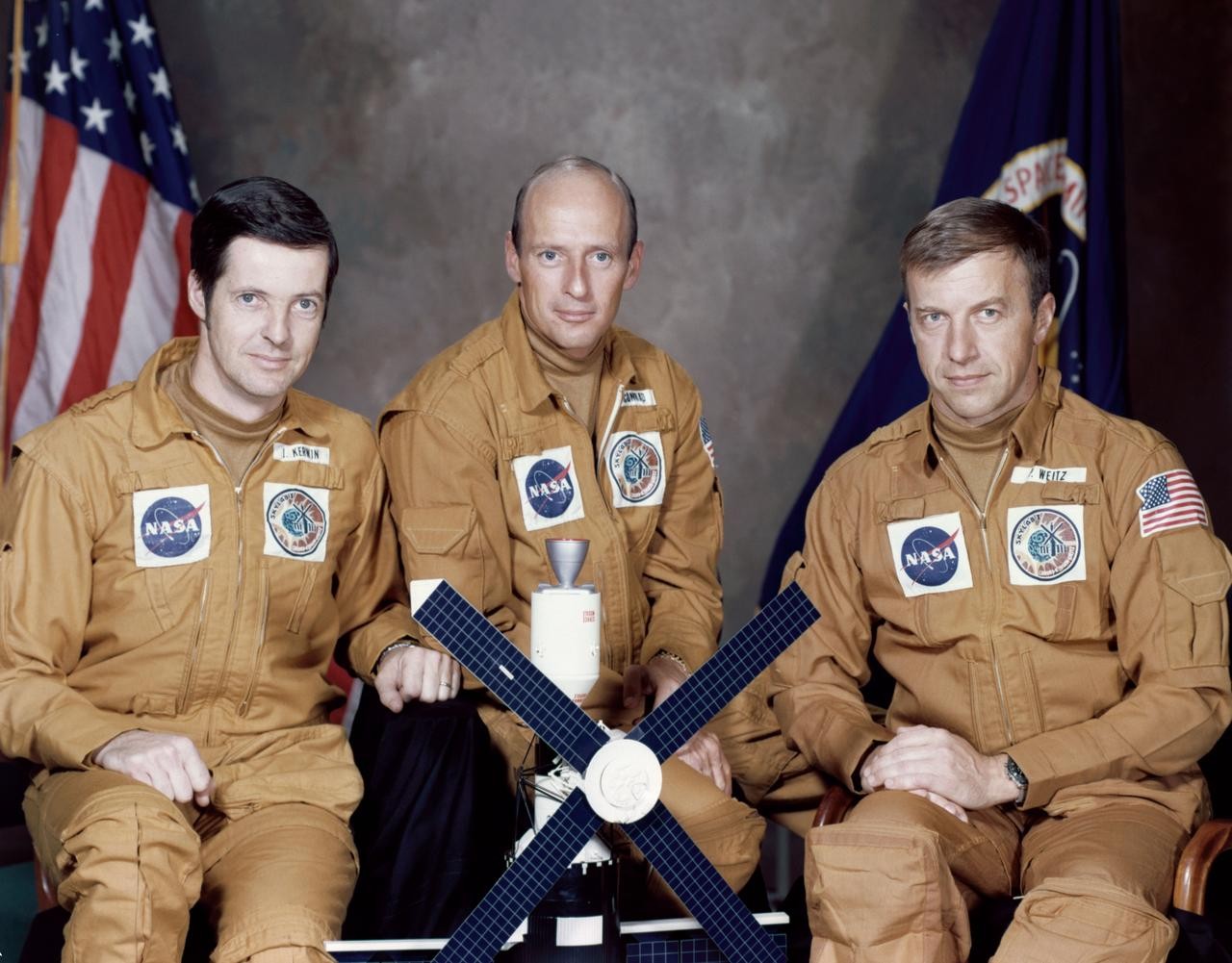

Today in Naval History—America’s First Space Station Launched

On May 14, 1973, Skylab, America’s first space station, was successfully launched into the Earth’s orbit from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. On May 25, Skylab 2, the first U.S. manned orbiting space station, was launched with an all-Navy crew—Capt. Charles Conrad Jr., Cmdr. Paul J. Weitz, and Cmdr. Joseph P. Kerwin—to operate the space station and conduct scientific experiments. Originally, Skylab 2 was to launch 24 hours after the first Skylab, but problems arose during its launch that nearly derailed the mission altogether. First, NASA delayed Skylab 2’s launch by five days and, as troubleshooting continued, another five days until it was finally launched 11 days after Skylab. Engineers, managers, and astronauts at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and the Johnson Space Center in Houston worked around the clock to find a solution to lower the space station’s internal temperature and to deploy the solar arrays to allow the Skylab program to continue. After the problems were rectified, the crewed portion of the Skylab project went forward. During the mission, the Skylab 2 crew conducted research in several areas to include life sciences—in particular the astronauts’ physiological responses—earth sciences, and solar physics and astronomy, with additional experiments in materials processing. After completing 404 orbits, the crew’s lunar module splashed down on June 22 in the Pacific Ocean. It was recovered by USS Ticonderoga (CV-14).

There were three successive crews of three astronauts that spent 28, 59, and 84 days aboard the orbiting laboratory, conducting 270 experiments. Skylab 3 launched on July 28, 1973, and Skylab 4 launched later that year on Nov. 16. Of note, Skylab 3 had two naval aviators on the crew, Alan Bean and Marine John R. Lousma. Skylab 4 had one naval aviator, Marine Gerald P. Carr. All three of the manned Skylab missions met their planned days in space with both Skylab 3 and Skylab 4 exceeding their targets by 3 and 28 days, respectively. Skylab 2’s 28-day mission aboard the space station broke the 24-day endurance record that had been set by the Soviets two years earlier on Salyut, the world’s first space station. (The Soviet mission had been plagued by problems. All three cosmonauts had died upon reentry due to the sudden depressurization of their spacecraft and, later, controllers had guided the space station into a destructive reentry over the Pacific Ocean after 175 days in space). However, the American space station was a great success and, most importantly, everyone lived through the missions’ completion. The crews of Skylab spent more than 700 hours observing the sun and brought home more than 175,000 solar pictures. They also provided important information about the biological effects of living in space for prolonged periods of time.

The Skylab complex was massive and complex for the time. It consisted of four major components: the orbital workshop (OWS), the airlock module (AM), the multiple docking adapter (MDA), and the Apollo telescope mount (ATM). The Apollo command and service module transported crews to and from Skylab and remained attached to the station throughout a crew’s occupancy to serve as an emergency escape vehicle. The OWS served as the main working, living, and sleeping compartment for the crews, and contained exercise equipment, a galley, and many of the scientific experiments for the life sciences studies. Two large solar arrays on the OWS provided power to the station. The AM enabled astronauts to conduct spacewalks, while the MDA included a prime and backup docking port for the Apollo spacecraft and also housed an earth resources experiment package. The ATM contained telescopes for solar observations and four solar arrays for additional power. Once in orbit, the complex weighed 170,000 pounds, by far the heaviest spacecraft at that time.

Five years after the last Skylab mission, the space station’s orbit began to deteriorate faster than expected, due to unexpectedly high sunspot activity. On July 11, 1979, the parts of the space station that did not burn up in the atmosphere came crashing down on Australia and into the Indian Ocean. No one was injured. For more on the Navy’s role in space exploration, visit NHHC’s website. Of note, the Skylab 2 command module, on loan from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, is on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.