Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

The Battle of Okinawa—World War II’s Last Amphibious Assault

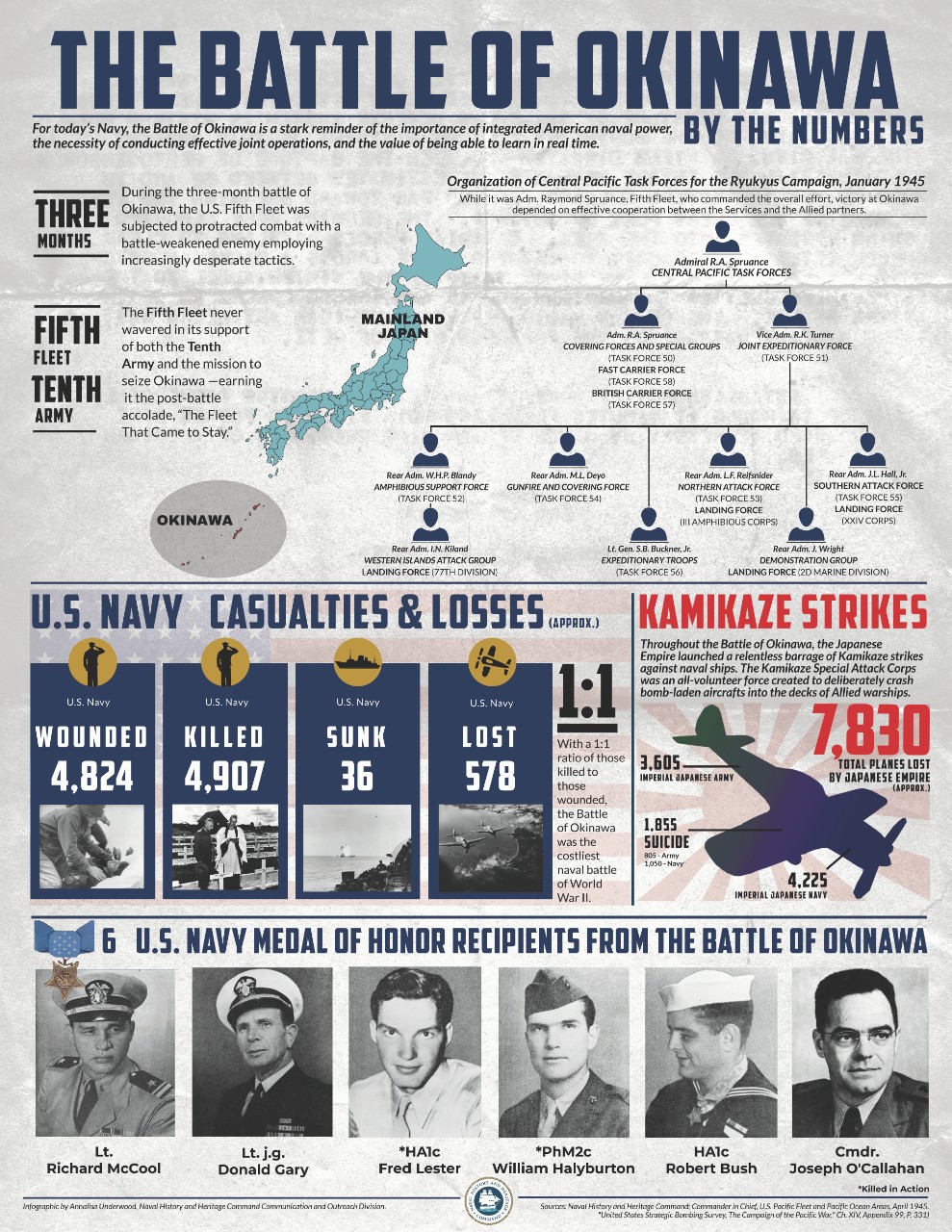

On April 1, 1945, under heavy naval gunfire and air support, U.S. Marines and Soldiers stormed the beaches of Okinawa in the last major amphibious assault of World War II. The capture of Okinawa—the largest island in the Ryukyus chain—was considered a vital precursor to a potential ground invasion of Imperial Japan. Leading up to the landings, more than 1,600 ships and 350,000 naval personnel assembled to form one of the largest amphibious assault forces of the war. However, before an invasion of mainland Japan could even be considered, American forces would have to endure nearly three months of one of the war’s bloodiest battles. On March 19, a preview of what awaited American forces occurred while Task Force 58 conducted bombardment strikes on mainland Japan in an effort to blockade the enemy’s supply lines. During the strikes against Kobe Harbor on the home island of Honshū, aircraft carrier USS Franklin (CV-13) was hit by two 550-pound, semi-armor-piercing bombs from a Japanese twin-engine dive bomber that managed to evade antiaircraft fire. The crew ultimately saved the ship, but the aircraft carrier was out of commission for the Battle of Okinawa and still under repairs when the war ended. The catastrophic bombing of Franklin resulted in a devastating number of casualties—796 killed and another 265 wounded.

Although the Japanese had dealt the Allies several significant blows leading up to the Okinawa landings, their capabilities were greatly diminished at this point in the war. U.S. planners expected that the ferocity of their resistance would continue to increase, however, as American forces got closer to Japan. With action now mainly concentrated around the central Philippines and the Ryukus, the Japanese were able to bring their land-based aircraft from Taiwan and the home island of Kyushu to the fight. However, these would not be used to conduct a conventional air campaign. Instead, the Japanese intended to use their land-based aircraft as human-guided bombs against U.S. forces. Such tactics, known as kamikaze (“divine wind”), had been used sporadically at Leyte Gulf, Luzon, Lingayen, and Iwo Jima, but not on the particularly large scale that was expected off Okinawa. With Fifth Fleet so close to mainland Japan, Navy planners feared that as many as 3,000–4,000 enemy planes could be expected. Unfortunately, their estimates were correct, with the prolonged land battle enabling the Japanese to launch numerous air attacks that were more successful than anticipated.

On March 31, the day before the invasion, Adm. Raymond Spruance got an early taste of what the Japanese had planned. After his flagship, USS Indianapolis (CA-35), shot down six enemy planes and assisted splashing two others, lookouts spotted a lone Japanese single-engine fighter as it roared toward the bridge in a vertical dive. The ship’s 20-millimeter guns opened fire, but less than 15 seconds after it was spotted, the plane continued to dive straight for the ship. Tracer shells pummeled the plane, causing it to swerve. Nevertheless, the enemy pilot managed to release his bomb from a height of 25 feet and subsequently crash his plane on the port side of the after main deck. Although the kamikaze strike did not cause catastrophic damage, the bomb blew two gaping holes in the ship’s bottom and flooded compartments in the area, killing nine of the crew. Indianapolis managed to steam to a nearby salvage ship for emergency repairs, but after inspection, it was found that its propeller shafts were damaged, its fuel tanks were ruptured, and its water-distilling equipment was ruined. Indianapolis was forced to leave the battle and make the long trip across the Pacific to the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, for repairs.

Despite the immense threat from the skies, the initial stages of the Battle of Okinawa, code-named Operation Iceberg, went as planned. Minesweeping, pre-invasion bombardments, and tactical strikes from aircraft carriers paved the way for an uncontested amphibious landing of Marines from the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions and Tenth Army’s 7th, 27th, and 96th Divisions (totaling more than 60,000 Marines and Soldiers). The force landed on the western side of the island close to two airstrips. Surprisingly, these were taken uncontested. Immediately afterward, the ground force split. Marines moved northeast to secure the northern part of the island, and the Army moved south toward Shuri. Although American forces faced little to no resistance upon landing, by April 6, Japanese forces began to defend the island fiercely. Thirty-four U.S. Navy ships were hit by kamikazes off Okinawa in the first of 10 large-scale attacks as part of the Japanese Ten-ichi-go (“Heaven One”) air and surface operation. The first attack lasted five hours and involved 355 kamikazes and more than 300 fighter escorts. The following day, the American task force launched approximately 380 aircraft, notably sinking battleship Yamato with most of its crew. By mid-April, the Marines secured their less-defended portion of the island, but the Army faced a more formidable Japanese defense, which led to a slower, more methodical advance. Later, the Marines joined the Army to slug it out with the Japanese, but both suffered high casualties against the well-defended Shuri Line. The fierce fighting and the appalling numbers of U.S. casualties continued into June, with the total number reaching 49,151, of which 12,520 were killed or missing. Under persistent and merciless kamikaze attacks, the Navy had 4,907 Sailors killed and 4,824 wounded. It is estimated that nearly one out of seven Navy deaths during the entire war occurred during the bloody months off Okinawa. In addition, the Navy lost 36 ships and craft, mostly by kamikaze attacks, and 578 naval aircraft.

By June 22, American forces had overwhelmed the island’s defenders, and Okinawa was declared secure. As it was so close to the Japanese mainland, most of the remaining enemy soldiers, desperate to die with honor, refused to surrender and either fought to the death or committed suicide. Some 110,000 Japanese and conscripted Okinawan defenders were ultimately killed in action during the Battle of Okinawa. In addition, the battle created a humanitarian disaster for civilians. Exact numbers are impossible to know, but some estimate that more than 100,000 civilians or as much as one-third of the pre-war population perished during the battle.

With Iwo Jima and Okinawa secured, the American military had considerable latitude as to how it would conduct the war going forward. The human cost of those bloody battles raised serious questions among the American public and military leaders as to the practicality of invading Japan, however. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died shortly after the beginning of the Okinawa campaign, President Harry S. Truman would have to make the decision how much more bloodshed the nation was willing to endure to secure Japan’s unconditional surrender. With the lessons learned from the Okinawa battle fresh in his mind, Truman would make the fateful decision to drop two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing the war to a close. The Battle of Okinawa became not only the final major engagement of the war, but a grim testament to what the future might have held for U.S. and Allied forces had they continued onward to the Japanese mainland. Operation Downfall, the planned invasion, occupation, and unconditional surrender of Japan, would have required at least an estimated 1.7 million U.S. troops. In late July 1945, the War Department estimated that the entire operation could lead to 400,000 to 800,000 U.S. killed. Japan would have potentially suffered 5 to 10 million deaths, wiping out most of its population.

***

Print Edition of NHHC’s History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915–2015, Released

Naval History and Heritage Command announces the release of the hard copy edition of History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915–2015. The book, originally published as a digital edition (508-compliant PDF) in 2021, was written by Dr. Thomas Hone, a former senior defense official, and Curtis Utz, a historian at NHHC. It provides a significant historical account of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV), shedding light on the influential individuals who left an indelible mark on the U.S. Navy’s history and strategic evolution.

Drawing on five years of research, the book offers readers a captivating narrative that goes beyond the battles at sea to uncover the bureaucratic battles that have shaped the Navy’s organization, planning, policies, and strategies over the past century. It delves into the lives and legacies of admirals, especially the Chiefs of Naval Operations, who played pivotal roles in the development of OPNAV and the Navy itself. It also explores instances when Secretaries of the Navy, Secretaries of Defense, or even Presidents intervened to drive policy because of changing circumstances and their views of national imperatives.

“This book examines the challenges that CNOs and OPNAV have faced over a century, and it provides insight to how and why Navy leadership made policy decisions,” said Utz. “Although the authority of the CNO and the organization of OPNAV have changed over the years, they are still primarily responsible and accountable for shaping and fielding a naval force capable of implementing national strategy.”

One consistent theme throughout the book is the unwavering commitment of CNOs to leave the Navy stronger and better managed than they found it. This book examines the strategies and measures employed by these leaders to achieve this goal and provides valuable insights into effective leadership within the U.S. Navy. Although History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915–2015, is not intended to be a manual of leadership, it offers readers an understanding of how leadership within the Navy evolved in response to an ever-changing environment, both in Washington, DC, and the world.

“As a student of history, I believe that in order to move forward we should look to the past for insights and lessons on how we, as a Navy and a nation, have navigated similar challenges,” said the 33rd CNO Adm. Lisa Franchetti. “Our Navy has been most effective at driving change and developing warfighting advantage when successive CNOs move with urgency and commitment toward the same goal."

To view this publication or other digital editions of recent NHHC publications, visit NHHC’s publications page. All digital publications are free to download from NHHC’s website.

***

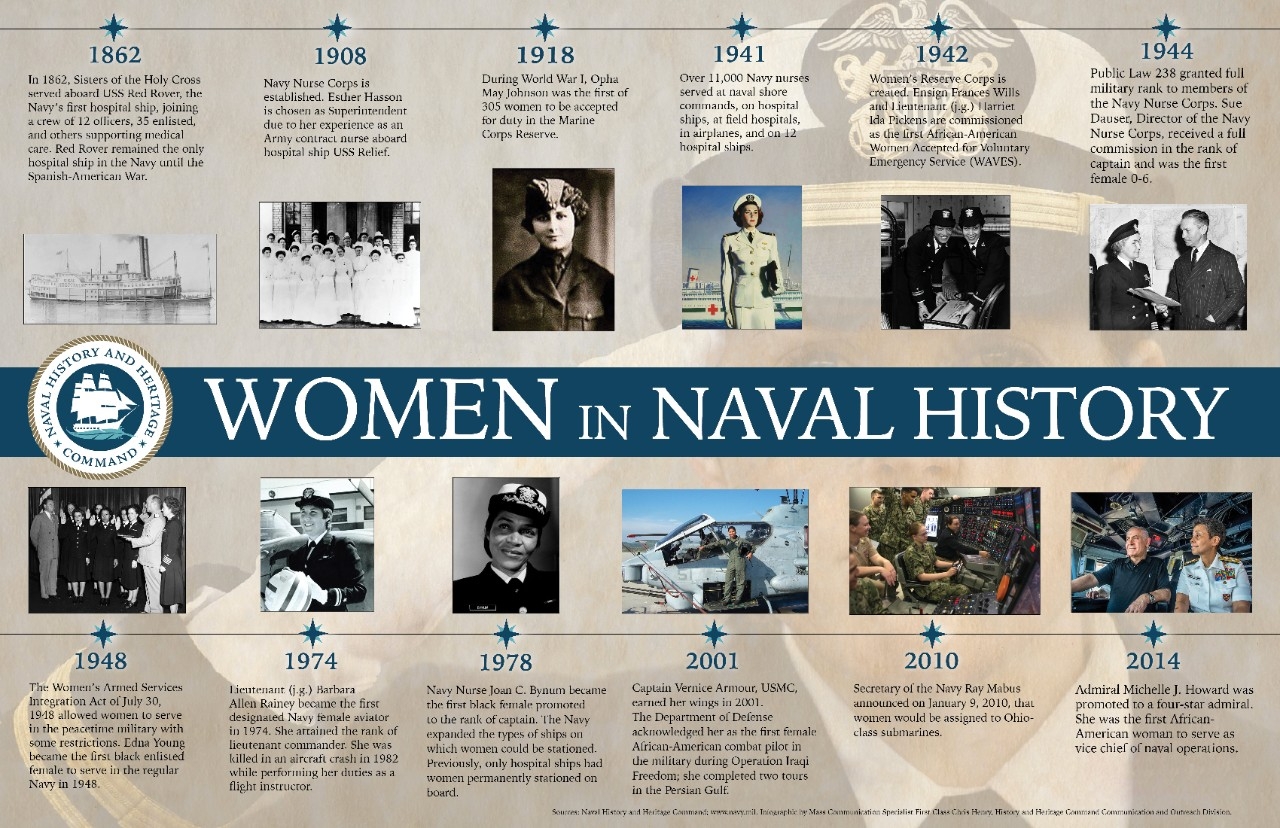

Women’s History Month: End of an Era—Last American Female Veteran of World War I

March 27, 2007, marked the end of an era when Charlotte Louise Berry Winters passed away peacefully at a nursing home in Boonsboro, Maryland. She was 109. She was the last known American female veteran of World War I and the last of the more than 11,000 women who had enlisted during the “Great War,” serving in support positions. She was buried with full military honors at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland. (Of note, Florence Beatrice Green, who served in the Women’s Royal Air Force, was the world’s last known surviving veteran of World War I. She passed away in February 2012 at 110. Frank Buckles, who served in the Army during World War I, was the last American male. The British Royal Navy’s Claude Choules was the world’s last known combat veteran from World War I. Both died at 110 years old in 2011 about six months apart).

Born on Nov. 19, 1897, in Washington, DC, to Mackell and Louise Berry, Winters graduated from Washington Business High School in 1915 and immediately sought to promote her newly acquired secretarial skills to the U.S. Navy. In 1916, the outgoing 19-year-old was presumptuous enough to make an appointment with Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels, hoping to persuade him to allow women to become Sailors. She maintained that female Sailors would be able to take over clerical duties, thus freeing up men for combat duty as the United States prepared for war. Initially, Daniels said no, but in March 1917, with the United States entry into World War I imminent and with shore stations desperate for clerks and stenographers, he changed his mind. Subsequently, Winters and her younger sister, Sophia, enlisted in the Navy. From 1917 to 1919, Winters served as a yeoman (F) at the U.S. Naval Gun Factory (today’s Washington Navy Yard) as a clerk. During the war, the Naval Gun Factory was the manufacturing center for all ordnance in the Navy. Discharged on July 31, 1919, she remained at the Washington Navy Yard as a civilian secretary until her retirement in 1953, after 35 years of federal service. During her off-duty hours while working at the yard, Winters helped establish the National Yeoman (F) Association and served as its eighth commander from 1940 to 1941. She was also active for 88 years in the USS Jacob Jones Chapter No. 2 of the American Legion, where she coordinated various activities throughout the Washington, DC, area.

Winters’s love for the Navy extended its way into her personal life as well. In 1949, she married fellow former Sailor John Winters, who worked as a machinist on the Washington Navy Yard. The two were avid Civil War historians, and their passion for documenting war strategies and the lives of those who had participated in that conflict took them all over the country. The couple lived in a pre–Civil War era home in Maryland—which they restored and modernized themselves—until John’s death in 1984. In her final years, Winters made her home at the Fahrney-Keedy Senior Residential Home in Boonsboro, where she remained active, enjoying reading and corresponding with friends. When she had initially moved to the nursing home in 1990, she confided to her friends that the only reason she moved there was because she didn’t want to cook anymore. She was 94 at the time.

After her passing, then–Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Michael G. Mullen reflected on her service: “Ms. Winters was a trailblazer, one of a relatively small group of women to serve in our Navy during World War I. She did so honorably and nobly, helping through that service to bring freedom to millions of people all across Europe and hope to thousands of young women across America. She and her shipmates answered the call when the nation needed them most. . . . They were patriots, and we will remain forever in their debt."

The first women to serve in the U.S. Navy were nurses, beginning with the “Sacred Twenty” appointed after Congress established the Navy Nurse Corps on May 13, 1908. The first large-scale enlistment of women into the Navy met clerical shortages during World War I. The second came months before the United States entered World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Public Law 689, creating the Navy’s women reserve program on July 30, 1942, which paved the way for women to enter the Navy as enlisted personnel and officers. On Feb. 22, 1974, the Navy designated the first woman as a naval aviator. On March 7, 1994, the Navy issued the first orders for women to be assigned aboard a combatant ship, USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69). Today, women serve in every rank from seaman to admiral and in every job from naval aviator to diver. For more on women in the U.S. Navy, visit NHHC’s website.

***

Today in Naval History—David R. Ray’s Selfless Actions

During the early morning hours of March 19, 1969, during the Vietnam War, an estimated battalion-sized force (300–1,000 enemy soldiers) launched a surprise attack against the position of Battery D, 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines, 1st Marine Division, in Phu Loc Six near An Hoa in the Quang Nam Province, Republic of Vietnam. Heavy fire from mortars, rockets, flamethrowers, grenades, and small arms battered the area as the enemy penetrated the barbed-wire perimeter—resulting in numerous casualties. Ignoring the incoming fire, Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class David R. Ray moved from casualty to casualty, rendering aid to as many Marines as possible. Although seriously wounded himself while assisting one of the casualties, Ray refused medical treatment and continued lifesaving efforts. At one point, as he was tending to a wounded Marine, two enemy soldiers attacked his position, forcing him to defend himself by killing one and wounding the other. Although quickly losing strength due to his own wounds, Ray continued to treat other casualties, taking up arms to defend his patients until he ran out of ammunition. When a grenade landed close to a wounded Marine he was treating, Ray threw himself on the body of his patient to protect him from the blast. Fragments from the grenade killed Ray instantly. For his selfless devotion to duty, Ray was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. His family was presented the nation’s highest honor on April 20, 1970, during a ceremony hosted by Vice President Spiro T. Agnew. Ray was returned to his home of McMinnville, Tennessee, and laid to rest in Mountain View Cemetery.

“Bobby,” as he was known to his family and friends, was born to David and Donnie Ray of McMinnville on Feb. 14, 1945. After graduating from McMinnville City High School in 1963, he attended the University of Tennessee in Knoxville for the next three years. On March 28, 1966, at the age of 21, Ray enlisted in the U.S. Navy in Nashville. After completing recruit training at the U.S. Naval Training Center in San Diego, he went on to complete Naval Hospital Corps School, also in San Diego. After he was promoted to hospital corpsman, Ray was assigned to USNS Haven (AH-12), but he was transferred to Naval Hospital Long Beach, California, in December 1966, after Haven was decommissioned. In May 1968, Ray reported for training at the Field Medical Service School at Camp Pendleton, California, and in July, reported to the 1st Marine Division in the Republic of Vietnam.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Ray also received the Purple Heart, the Combat Action Ribbon, the National Defense Service Medal, the Vietnam Service Medal with star, and the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal. Launched on Aug. 23, 1974, Spruance-class destroyer USS David R. Ray (DD-971) was named in his honor. Nicknamed “Sting Ray,” the ship played a critical role in the early stages of Operation Desert Shield and multiple maritime interception and counter-narcotic operations before it was decommissioned in February 2002. In addition, the David R. Ray Clinic at Naval Station Everett, Washington, and the David R. Ray Branch Health Clinic at Marine Base Quantico, Virginia, are named in his honor.