Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On April 4, 1933, rigid airship Akron (ZRS-4) crashed tail first and sank in a violent storm off the New Jersey coast. Among the 73 killed was Medal of Honor recipient Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, who was the first chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics. German motor ship Phoebus was in the vicinity and saw lights descending at about 12:23 a.m. It altered course to investigate, thinking it was a plane crash. About 30 minutes later, the crew of Phoebus picked up an unconscious Lt. Cmdr. Henry V. Wiley, Akron’s executive officer, while a boat from Phoebus picked up three more survivors—Chief Radioman Robert W. Copeland, Boatswain's Mate 2nd Class Richard E. Deal, and Aviation Metalsmith 2nd Class Moody E. Erwin. Despite desperate artificial respiration efforts, Copeland subsequently died on board Phoebus. The German ship combed the area with its boats for more than five hours in a fruitless search for more survivors of aviation’s biggest single tragedy to that date. Navy blimp J-3 was sent out to join the search, but also crashed in the storm with the loss of two men.

Coast Guard destroyer Tucker (CG-23), the first U.S. ship on the scene, arrived at the accident site at around 6 a.m. and took the survivors and the body of Copeland on board. Among the other ships that combed the area were heavy cruiser Portland (CA-33), destroyer Cole (DD-155), Coast Guard cutter Mojave, and Coast Guard destroyers McDougal and Hunt. U.S. Navy Reserve aircraft searched the crash site as well. Akron’s loss spelled the beginning of the end for the rigid airship in the Navy, especially since one of its leading proponents, Moffett, perished with it. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt commented afterward: “The loss of Akron with its crew of gallant officers and men is a national disaster. I grieve with the nation and especially with the wives and families of the men who were lost. Ships can be replaced, but the nation can ill afford to lose such men as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett and his shipmates who died with him upholding to the end the finest traditions of the United States Navy.”

The Navy launched its lighter-than-air program when it awarded its first contract for an airship, DN-1, to the Connecticut Aircraft Company in June 1915. During construction of DN-1, the Navy authorized construction of a hangar to house the new airship, which was completed in early 1916. DN-1 arrived in Pensacola, Florida, in December 1916, but the airship was not ready for flight until April 1917. Once test flights began, multiple problems were revealed. The airship was severely damaged during one of the test flights, and it was never repaired. Even before DN-1 was built, studies were ongoing at the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a future class of dirigibles. In April 1916, the General Board endorsed the development of zeppelins and other mobile lighter-than-air craft. At Akron, Ohio, the Navy’s program tested non-rigid airships, free balloons, and kite balloons. During testing, the balloons were found to be an easy target for enemy aircraft, and they restricted maneuverability when moored to a ship. During World War I, airships and kite balloons were used in conjunction with seaplanes and flying boats to help protect shipping. They were also used to detect submarines and warn vessels of mines. Most of the airship patrols were carried out off the U.S. East Coast and in Europe, where they were deemed successful because they were a deterrent to German submarines.

When the Armistice was signed in 1918 and the “Great War” was over, the development of non-rigid airships became more advanced with more capabilities. The Navy contracted Goodyear to build airships, and hangers were built to accommodate them. The airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) was the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium and the first to fly across the United States. On Sept. 3, 1925, while flying over Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a severe storm that broke the airship in two, killing about half the crew. The most successful airship of the time was Los Angeles (ZR-3). The airship was built by Germany and given to the U.S. as compensation for the loss of two airships that were lost during the war. Los Angeles was in operation more than seven years and made more than 330 flights.

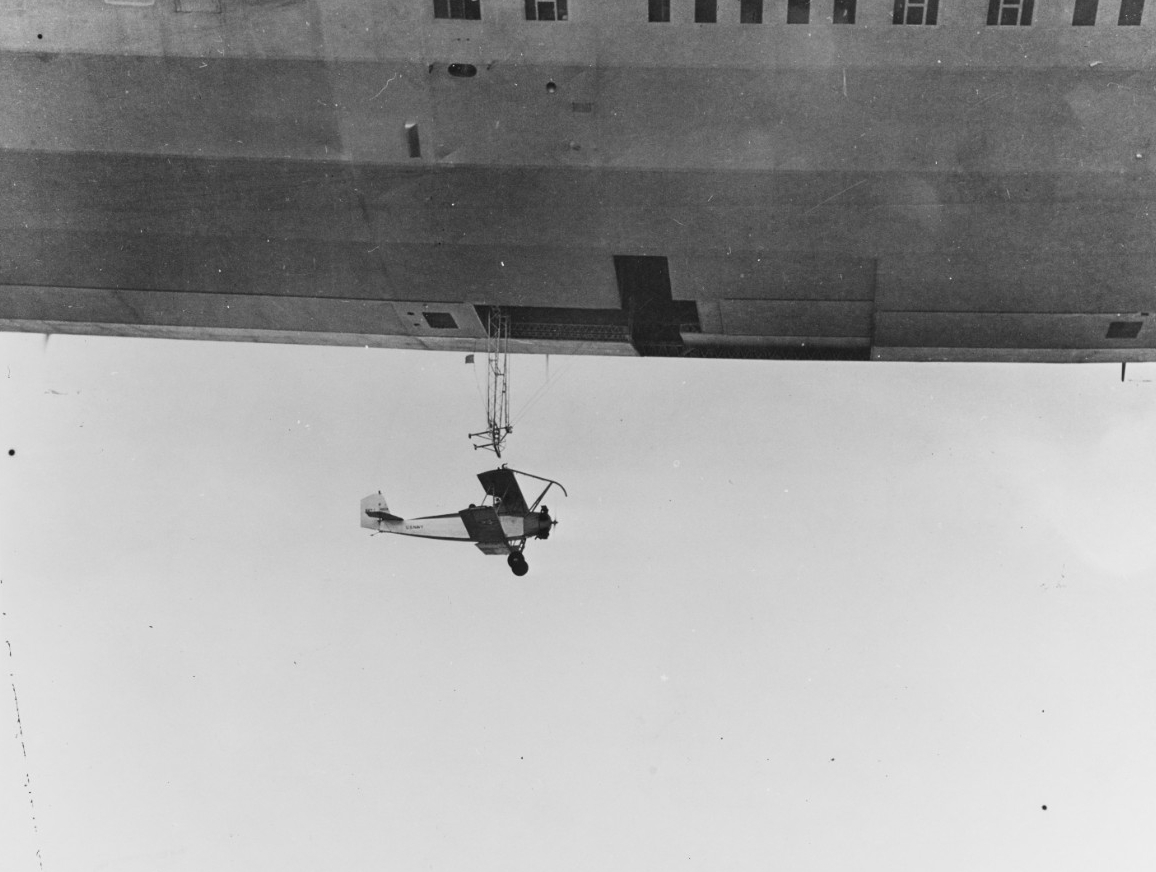

Probably the most prolific period in the Navy’s construction of rigid airships was during the era of Akron and Macon (ZRS-5). They were viewed as an improvement from the Shenandoah design, having the ability to house and carry other aircraft, although they ended up being the first and last flying carriers. In addition to the loss of Akron, Macon was also lost during a storm off Point Sur, California, on Feb. 12, 1935.

During World War II, there were five different airship classes/types in the Navy’s inventory. Airship operations and expansion were unprecedented. The airship fleet conducted operations in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and Atlantic. When the war was over and the military drew down, the Navy kept two squadrons that conducted mostly training, search and rescue, observation, and photography missions.

On June 21, 1961, the Office of the Secretary of the Navy announced it was going to terminate the Navy’s lighter-than-air program. The last flight of a naval airship occurred on Aug. 31, 1962.

Samuel B. Roberts Struck Iranian Mine

In April 1988, USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) was participating in Operation Ernest Will in the Arabian Gulf. The United States launched the operation to protect reflagged Kuwaiti tankers during the Tanker War phase of the Iran-Iraq War. On April 14, Samuel B. Roberts was on its way to meet USS San Jose (AFS-7) to replenish stores when a lookout, Seaman Bobby Gibson, spotted three mines ahead in an area that had already been swept by coalition minesweepers. Once he confirmed the ship had entered a minefield, Cmdr. Paul Rinn quietly ordered his men to battle stations without sounding the alarm to avoid panicking the crew or triggering mines. He also ordered his men below to come topside in the event of mine damage below the waterline. Rinn weighed his options and decided to attempt to follow the ship’s wake to exit the minefield. “I thought,” he afterward noted, “we came in that way so we probably could go out that way.” The ship reversed engines, but at 4:49 p.m. hit an Iranian moored contact mine. The explosion lifted the ship into the air, drove its bow down into the water, and blew a 21-foot hole on the port side. The impact damaged the hull, deckhouse, and foundation structures, and burning fuel shot a column of fire from the stack. The blast shook the main engines from their mountings, flooded the engine room, opened cracks in the superstructure, and caused a split in the ship’s bulkhead between the main engine room and an auxiliary machinery room. Ten Sailors sustained severe injuries, and four were seriously burned. Rinn broke the metatarsal bone in his left foot from the shock wave of the blast. When considering whether to abandon the ship, Rinn noticed swarms of snakes and sharks in the water. This persuaded him to stay and fight for the ship, because of the realization that men would die if they abandoned ship.

Rear Adm. Anthony A. Less, commander of Joint Task Force Middle East/Middle East Force, radioed Rinn several times from his flagship, USS Coronado (AGF-11), and at one point asked him to evaluate the possibility of losing Samuel B. Roberts. “No higher honor,” Rinn replied in reference to when the Japanese sank the first Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) during the Battle of Leyte Gulf on Oct. 25, 1944. That ship’s survivors had pulled Cmdr. Robert W. Copeland, their commanding officer, from the water, and Copeland said he could think of “no higher honor than to have served with these men.”

Intensive training of the crew and their valiant dedication ultimately saved the ship. American, British, Dutch, French, and Italian ships swept the 10 miles surrounding the area where the frigate struck the mine, and then expanded their search another five miles, locating eight additional mines of Iranian origin. Lack of barnacles or marine growth on the devices revealed they were recently deployed. On April 17, Samuel B. Roberts was towed into Dubai for dry-docking and temporary repairs. Several months later, Dutch heavy-lift ship Mighty Servant carried the frigate to a dry dock at Bath Iron Works in Maine. On April 18, the U.S. Navy launched Operation Praying Mantis against Iranian targets in the Arabian Gulf in retaliation. In the one-day operation, the U.S. Navy destroyed two Iranian surveillance platforms, sank two of their ships, and severely damaged another.

On May 3, medals were presented to the crew of Samuel B. Roberts for their actions in saving the ship. Rinn received the Legion of Merit, and the crew received the Navy Unit Commendation award as well as the following individual awards: 10 Bronze Stars, 14 Navy Commendation Medals, and multiple Purple Hearts. In addition, Rinn was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal with Combat Distinguishing Device for his “superior performance and management of the wounded,” along with the U.S. Navy League John Paul Jones Inspirational Leadership Award. He also received an Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal.

From 2004 to 2008, Samuel B. Roberts participated in drug interdiction and relief operations in the U.S. Southern Command’s area of responsibility. While deployed to the Mediterranean in 2010, the ship set a new Navy record for the flight hours of its embarked Northrop Grumman MQ-8B Fire Scouts. Samuel B. Roberts was decommissioned on May 22, 2015.

War Declared on Germany

On April 4, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted 82 to 6 in support of a measure to declare war on Germany. Two days earlier, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war. Wilson cited Germany’s violation of its pledge to suspend unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean, as well as its attempts to entice Mexico into an alliance against the United States (Zimmermann Telegram), as his reasons for declaring war. On April 6, the House concurred with the Senate on a vote of 373 to 50. A few months later, the United States declared war on German ally Austria-Hungary.

On April 24, Division Eight, Destroyer Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, under command of Cmdr. Joseph T. Taussig, departed Boston for Queenstown, Ireland, consisting of Taussig’s flagship Wadsworth (DD-60), Conyingham (DD-58), Porter (DD-59), McDougal (DD-54), Davis (DD-65), and Wainwright (DD-62). After the destroyers arrived on May 4, Taussig paid a visit to British Vice Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly, commander, Western Approaches. Over dinner, Bayly asked Taussig when his flotilla would be ready, and as popular legend has it, Taussig replied, “We are ready now, Sir.”

At the time, the British were desperate for escorts as British grain stores had been reduced to a critical three-week supply. When the Germans resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917, more than 800 Allied ships had been sunk in just a matter of months. The destroyers’ prompt arrival was due in part to the presence in England of an American naval mission led by Vice Adm. William Sims. A few years before the beginning of World War I, Sims was president of the Naval War College. With the first Chief of Naval Operations William Benson, Sims and Benson anticipated a transatlantic naval war involving new challenges and technology. Ashore and through exercises, they studied the role of the Navy in modern warfare. By 1917, Benson anticipated a naval campaign in European waters that would require a naval headquarters in England. Sims proved the ideal officer for the job. He traveled to London, arriving on April 2, 1917, to establish direct contact between Benson, the Royal Navy, and other Allied naval forces.

After establishing the “London flagship,” Sims and his staff promoted American naval opinions when reviewing strategy with the British. They challenged the Royal Navy’s method of countering German submarines, insisting supply ships should steam in protected, escorted convoys. A trial convoy formed on May 10 at Gibraltar and made it to England without loss. A second protected convoy from Virginia to England also made it undamaged. After the two successful trials, all convoys were required to travel with escorts. By mid-June, the American destroyers were escorting troves of arriving merchant ships into European harbors. The escorted convoy strategy overcame the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign. The convoy system secured the passage of the American Expeditionary Forces to France along with vital supplies for all the Allies.

Over the course of the war, the most significant contribution of the U.S. Navy was the escort and transport of two million U.S. Soldiers to France, the great majority in the last six months of the war, with almost no losses to German submarines. By July 1918, U.S. troops were arriving in France at a rate of about 10,000 per day, roughly half in U.S. shipping and half in other Allied shipping. Although the U.S. Army had significant success on the battlefield against diminished German forces, it was the German High Command’s realization that there was nothing it could do to stem the tide of an overwhelming number of U.S. troops that ultimately caused the Germans to sue for peace.

Columbia Launched

On April 12, 1981, space shuttle Columbia (STS-1) lifted off at 7 a.m. from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida with an all-U.S. Navy crew: Capt. John W. Young was the shuttle’s commander, and Lt. Cmdr. Robert L. Crippen was the pilot. The launch of Columbia marked the inaugural flight for the nation’s space shuttle program into space. The flight was a test mission and was NASA's first crewed mission since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. The launch occurred 20 years to the day after the first human launch when cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth in the Vostok 1 capsule on April 12, 1961. The mission objective was to demonstrate the safe launch into orbit and return of the orbiter and crew. The mission also verified the combined performance of the entire shuttle vehicle, orbiter, solid rocket boosters, and external tank. Payloads included the Developmental Flight Instrumentation and the Aerodynamic Coefficient Identifications Package pallet containing equipment for recording temperatures, pressures, and acceleration levels at various points on the spacecraft. Columbia concluded its mission on April 14, with a touchdown at Edwards Air Force Base in California, after a 54-hour mission.

Between the first launch in 1981 and the final landing on July 21, 2011, NASA’s space shuttle fleet—Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour—flew 135 missions and helped construct the International Space Station. As humanity’s first reusable spacecraft, the space shuttle pushed the bounds of discovery ever farther, requiring not only advanced technologies but the tremendous effort of a vast workforce.

The two crewmembers for the initial Columbia space shuttle mission were both commissioned as naval aviators. This was the first space flight for Crippen, whereas Young had vast experience in space exploration with four previous space missions, including Apollo 16 in 1972, where he became the ninth person to walk on the moon. Young’s sixth and final flight into space was as spacecraft commander of STS-9, the first spacelab mission (Nov. 28–Dec. 8 1983). He retired shortly afterwards on Dec. 31, 1983. Crippen flew into space a total of four times. He spent more than 6,500 hours in the air as either a pilot or astronaut. For more on the Navy’s Role in Space Exploration, visit NHHC’s website.