Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On the evening of Feb. 21, 1945, USS Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) had just recovered its aircraft from a strike during the Battle of Iwo Jima when a swarm of Japanese planes appeared. In the ensuing attack, the escort carrier downed one enemy bomber, but another one crashed, kamikaze-style, into the ship. The crash knocked four torpedoes onto the hangar deck, parted the ship’s elevator cables, and damaged the after fire main. The fire was controllable at first, until its glow attracted another Japanese plane that also crashed into the ship, killing or mortally wounding the entire firefighting party. The subsequent explosion buckled bulkheads and collapsed the decks in the ammunition-clipping rooms. The planes on the hangar deck added fuel to the fires. Soon, these raged out of control and ordnance began to explode. The captain gave the order to abandon ship, and in less than 30 minutes, Bismarck Sea’s entire crew was in the water. After many explosions and two hours aflame, the ship rolled over and sank. Rough seas, cold water, and Japanese strafing took the lives of many members of the escort carrier's crew. Three destroyers and three destroyer escorts spent 12 hours picking up survivors, but 318 American Sailors were lost.

Also on Feb. 21, USS Saratoga (CV-3) was struck by five kamikazes in just a span of three minutes. Saratoga's flight deck forward was wrecked, its starboard side was holed twice, and fires started in its hangar deck. One hundred and twenty three of the ship’s crew were killed. Another attack later that evening scored an additional bomb hit. However, the fires were eventually brought under control, and the carrier was able to recover aircraft. Although the ship survived, it was subsequently ordered to Eniwetok, and then to the U.S. West Coast for repairs.

Kamikaze attacks became prevalent in October 1944 during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, when the outlook was becoming increasingly bleak for the Japanese. They had lost several important battles up to that point, many of their best pilots had been killed, their aircraft were becoming increasingly outdated, and they had lost control of airspace. In addition, Japan was losing pilots faster than they could train them. These factors, along with Japan’s unwillingness to surrender, led to the use of kamikaze tactics as Allied forces advanced toward Japan. The tradition of death instead of defeat or capture was deeply entrenched in Japan’s military—it was one of the values of the samurai way of life. In addition to kamikazes, the Japanese also used suicide submarines, speedboats, and even divers.

The use of kamikaze attacks peaked during the Battle of Okinawa. The first of 10 major kamikaze attacks, dubbed Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) Operation No. 1, occurred on April 6–7, 1945. U.S. forces off Okinawa were attacked by 355 kamikaze aircraft and another 340 planes in conventional strike and escort roles. U.S. intelligence knew the major attack was coming, and the ships received a general warning. In the initial wave, many of the kamikaze pilots fell prey to the large numbers of radar-directed U.S. Navy fighters. Those that made it through the fighter gauntlet tended to go after the first ship they saw, and U.S. destroyers on the northern radar picket stations bore the brunt of the attacks. Destroyers USS Bush (DD-529) and USS Colhoun (DD-801) were sunk during Operation No. 1. USS Emmons (DD-457) was also lost. From the Japanese perspective, the initial attack was not what they had hoped for, given the number of aircraft they lost. However, that wouldn’t stop nine more waves of attacks in the next two months. In total, 2,800 kamikaze attackers sank 34 U.S. Navy ships, damaged 368 other vessels, killed 4,900 U.S. Navy personnel, and wounded another 4,800 during the Battle of Okinawa.

TOPGUN Established

Initially attached to Fighter Squadron 121 (VF-121) and operated out of a trailer on Naval Air Station Miramar, California, the Navy’s Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor Course, also known as “TOPGUN,” was established on March 3, 1969. The school was originally created to train Navy fighter pilots during the Vietnam War. The school has become famous due to the 1986 film Top Gun and its 2022 sequel Top Gun: Maverick. Although TOPGUN appears to be an acronym, it actually doesn’t mean anything. It was a nickname created by the tactical department of VF-121 when the school was stood up. The name has stuck, because it’s easier to say than the Navy’s official name for the course.

During the Vietnam War, and despite having the technological advantage over the enemy, the Navy was experiencing unacceptable air combat losses. In response, the Navy launched an investigation and tasked Capt. Frank Ault to lead the effort. The findings—known as the Report of Air-to-Air Missile System Capability Review or more commonly as the Ault Report—highlighted performance deficiencies and their root causes, including the need for an advanced course to teach fighter tactics. The result was the Navy Fighter Weapons School. The school’s mission was, and still is today, to train aircrews in all aspects of aerial combat with utmost professionalism.

“When TOPGUN graduates began to go back to the fleet in the early 1970s and the air war started back up, the Navy’s kill ratio jumped. TOPGUN worked,” said retired Navy Cmdr. Dustin Peverill, a 20-year veteran and two-time TOPGUN instructor. “It validated that the training, the subject-matter expertise, and, most importantly, the professionalism that it produced worked in combat and it produced results.”

TOPGUN produces graduate-level fighter pilots, as well as adversary instructors and intercept controllers. After students complete the course, most go back to the fleet; however, some are invited to remain or return to the school and become instructors, but only 5 percent of Navy fighter pilots have the opportunity to teach at TOPGUN. TOPGUN averages about 35 instructors on staff at any one time. That includes strike fighter aircrew, airborne intercept controllers, and an intelligence officer. Most spend about three years on the staff. Unlike the original movie, which focused on the students, much more emphasis is placed on the instructors than students.

“A standard day for a TOPGUN instructor is anywhere from 12 to 16 hours. You're flying an airplane, you're studying, you're teaching, and you're answering emails from around the fleet,” explained Peverill. “Aviators continually reach back to the schoolhouse to ask questions. Our job is to make sure the fleet is knowledgeable.”

In 1996, TOPGUN moved, as part of the Base Realignment and Closure Program, to Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada, to be integrated into the newly created Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center (now known as the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center). As the F/A-18 Hornet’s role grew, the aircraft required more airspace and air-to-surface range space for training. The Fallon Range Training Complex was an ideal fit. Also in recent years, TOPGUN has incorporated the FA-18E/F Super Hornet and the F-35C Lightning into the training.

First Female Naval Aviator

On Feb. 22, 1974, Lt. (j.g.) Barbara (Allen) Rainey became the first woman to earn her wings of gold and be designated as a naval aviator during ceremonies at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas. She subsequently went on to serve with Pacific Fleet and flew a Grumman C-1A Trader based out of Alameda, California. Rainey also became the first woman in the Navy to qualify in a jet-powered aircraft, the North American Rockwell T-39 Sabreliner. In November 1977, Rainey resigned her active-duty Navy commission when she and her husband, John C. Rainey (whom she had met in high school), learned she was pregnant with their first of two daughters. While pregnant, she remained in the Naval Reserve and qualified to fly the Douglas R6D/C118 Liftmaster. In 1981, the Navy experienced a shortage of instructors, so Rainey went back on active duty as a flight instructor with the rank of lieutenant commander. She served with Training Squadron 3 (VT-3) based at Naval Air Station Whiting Field, Florida, where she flew the Beechcraft T-34C Turbo Mentor.

On July 13, 1982, while practicing touch-and-go landings with her trainee, Ensign Donald B. Knowlton, their T-34C crashed at Middleton Field near Evergreen, Alabama. While in the traffic pattern, the aircraft suddenly banked to the right and lost altitude. Both Rainey and Knowlton were killed. She was just 34 years old. Rainey is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Her headstone stone is inscribed, “First Woman Naval Aviator. Loving Wife and Mother.”

Born on Aug. 20, 1948, at Bethesda Naval Hospital, Rainey was the daughter of a career naval officer. She graduated from Lakewood High School, Lakewood, California, and was an outstanding athlete and consistently on the dean’s list at Long Beach Community College before she transferred to Whittier College, also in California. In November 1970, she was commissioned in the U.S. Naval Reserve during ceremonies at the U.S. Navy Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, and was assigned to Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek, Virginia, later transferring to Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) in Norfolk. Seeking a greater challenge and following in the footsteps of her U.S. Marine Corps aviator brother, Bill, she applied to and was accepted into naval flight training.

In early 1973, Secretary of the Navy John Warner announced a test program to train women to be naval aviators, and on March 2, Rainey and seven other women reported for flight school. Of the initial eight women to attend flight school, six graduated and were designated naval aviators. Since the first six earned their wings, naval aviation has expanded its roles dramatically for women to lead and serve globally. Today, women aviators fly in every type, model, and series of aircraft. They fly and fight all strike missions, hunt submarines, protect the integrity of the nuclear triad, supply essential cargo and personnel, and rescue those in distress at sea and at shore. They command aircraft carriers, carrier air wings, squadrons, and missions to space. For more on women in the Navy, visit NHHC’s website.

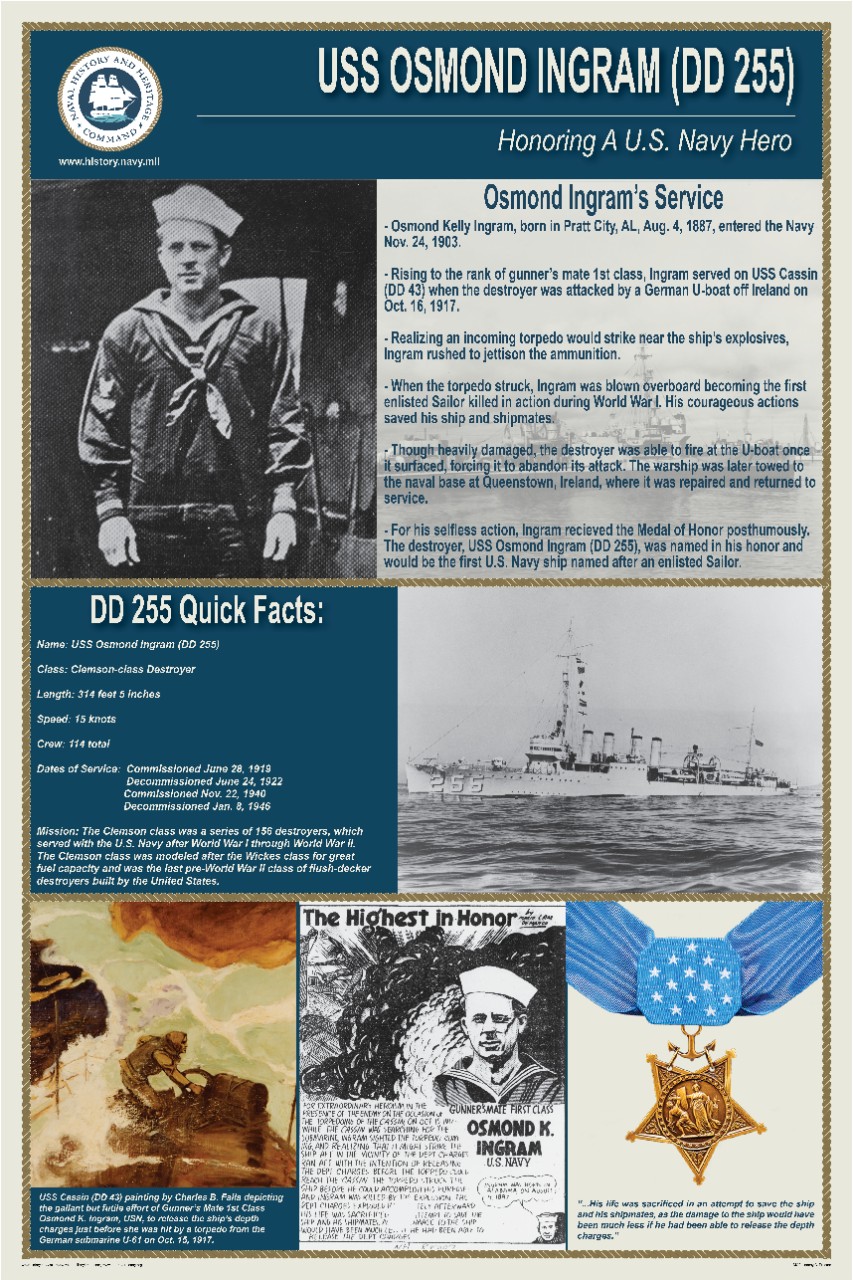

First Ship Named for Enlisted Sailor

On Feb. 23, 1919, the first ship named for an enlisted Sailor, USS Osmond Ingram (DD-255), was launched and commissioned in Boston on June 28. The ship’s namesake, Gunner’s Mate First Class Osmond Kelly Ingram, was born in Pratt City, Alabama, on Aug. 4, 1887, and entered the Navy on Nov. 24, 1903. On Oct. 16, 1917, while onboard Cassin (Destroyer No. 43), the crew sighted German submarine U-61 about 20 miles south of Mine Head, Ireland, and pursued the enemy boat. While Cassin was in pursuit, Ingram sighted a torpedo heading for his ship, and realizing that it might strike it aft in the vicinity of the depth charges, ran toward the area of impact with the intention of releasing the depth charges before the torpedo could reach Cassin. However, the torpedo struck the ship before he could accomplish this. The depth charges exploded immediately afterward. Ingram was killed by the explosion and nine others were wounded. Ingram gave his life in an attempt to save the ship and his shipmates. He was the first U.S. Sailor killed in action during World War I. Ingram was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously.

After commissioning, Ingram’s namesake ship served several years in the Atlantic before it was decommissioned on June 24, 1922, and went into reserve at Philadelphia. Converted to seaplane tender, Osmond Ingram recommissioned on Nov. 22, 1940, and sailed for San Juan, Puerto Rico. It tended patrol planes through the area bounded by Trinidad, Antigua, and San Juan, then steamed to a base in the Panama Canal Zone, where it tended patrol craft at Salinas, Ecuador, and in the Galapagos through June 1942.

Returning to destroyer duties, it completed 1942 as an escort between Trinidad and Recife and Belem, then headed north to Argentia, Newfoundland, to join a hunter/killer group formed around USS Bogue (CVE-9). Osmond Ingram sank its first enemy submarine, U-172, with gunfire on Dec. 13, 1943, after the enemy boat was forced to surface by depth charge attacks. Similar outstanding performances earned the group a Presidential Unit Citation.

After a convoy to Gibraltar early in 1944, Osmond Ingram served on escort duty between New York and Trinidad until June, when it entered Charleston Navy Yard, Massachusetts, for conversion to a high-speed transport. It joined amphibious forces in the Mediterranean in time for the pre-invasion assaults on the islands off the French coast on Aug. 14, 1944, then escorted convoys along the French and Italian coasts until making way for Norfolk, Virginia, late in December.

Now assigned to the Pacific, Osmond Ingram continued its valuable war service with escort duty en route via Panama to San Diego, Pearl Harbor, Eniwetok, and Ulithi. On April 2, 1945, it steamed with an assault force for Okinawa, and until that island was secured, alternately escorted fast convoys to Saipan and Guam and patrolled the seaward defense lines for Hagushi Anchorage. During July, it escorted ships between Leyte and Hollandia, New Guinea; in August, it began patrols through the Philippines and to Borneo. When the Japanese surrendered, Osmond Ingram aided in the occupation of Japan, calling at Wakayama, Kure, and Nagoya until the ship headed for the United States.

Osmond Ingram decommissioned at Philadelphia on Jan. 8, 1946. The ship received six battle stars for its World War II service.