Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

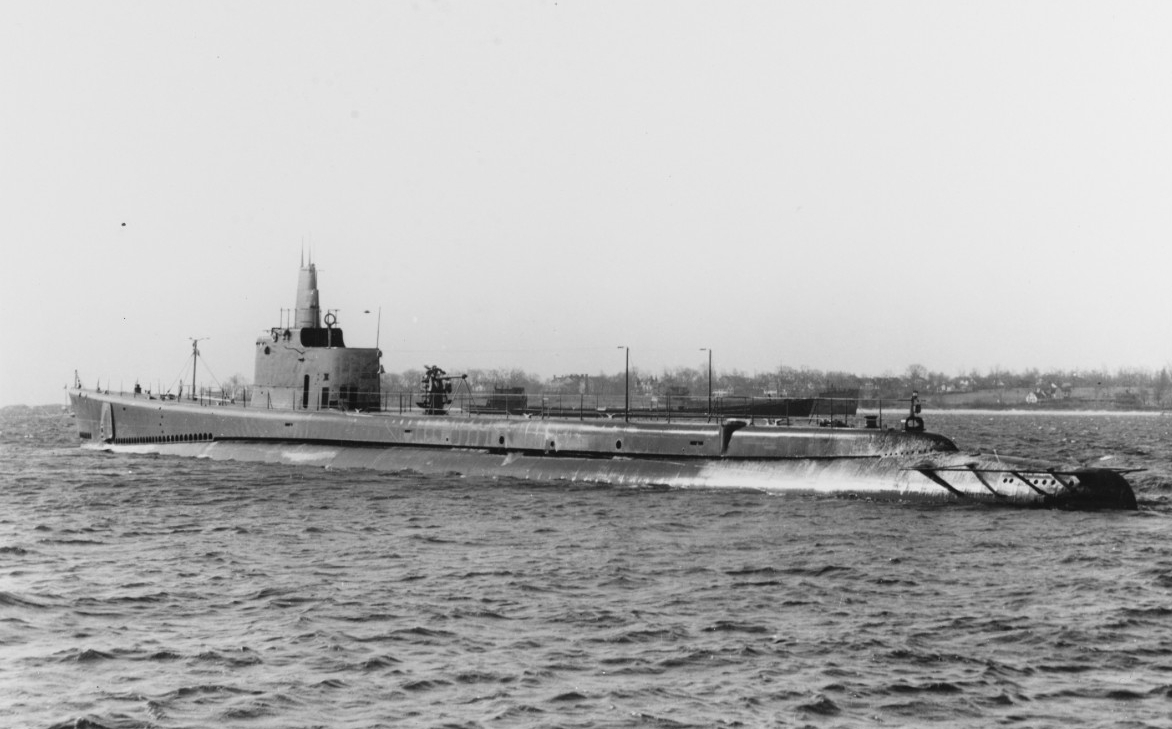

Today in Naval History

On Feb. 7, 1943, the crew of USS Growler (SS-215) sighted a small enemy vessel while on patrol near the Bismarck Archipelago (a small island group off the northeastern coast of New Guinea in the South Pacific). Whipping around to engage the Japanese ship, Growler prepared its torpedo tubes for a surface attack. The 900-ton stores ship Hayasaki, also in the area, spotted Growler and reversed course to attack the American submarine. Lt. Cmdr. Howard W. Gilmore, Growler’s commander, ordered left full rudder, sounded the collision alarm, and boldly rammed the enemy vessel at a speed of 17 knots. During the ensuing machine-gun battle, Gilmore was mortally wounded, and two others were killed on the bridge. An immediate order to clear the bridge sent the boat’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. Arnold F. Schade, and the quartermaster below. Gilmore, realizing he would endanger the submarine and crew due to his inability to get below deck because of his injuries uttered the legendary words, “Take her down.” After a brief hesitation, Schade followed his commander’s final order and closed the hatch. The Japanese continued to riddle the bridge with gunfire as Growler safely submerged. For his heroic sacrifice, Gilmore was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. He was the first of seven U.S. submarine commanders who received the nation’s highest honor during World War II. After the loss of Growler’s popular commander, the boat was ordered to end its patrol and make way for Australia.

After extensive repairs that included replacing the submarine’s bow, Growler got underway for its fifth war patrol. In mid-June 1943, Schade, now the commanding officer, spotted a convoy of eight enemy ships with three escorts. Chasing it on the surface, Shade ordered a spread of four torpedoes at the lead ship and an accompanying passenger-cargo ship, scoring two hits on each. The lead ship went dead in the water, and the passenger-cargo ship Miyadono Maru slipped below the waves. It was Shade’s first sinking as commanding officer.

Although Growler’s sixth, seventh, and eighth patrols were mostly uneventful, the submarine’s ninth patrol centered on conducting sweeps of the Saipan-Tinian island channels in anticipation of the upcoming Battle of Saipan. When the battle ensued, Growler was ordered to perform search-and-rescue duties for any downed airmen. Also during the patrol, Growler rendezvoused with USS Bang (SS-385) and USS Seahorse (SS-304) to form a wolf pack. On June 28, 1944, while the wolf pack steamed through the Balintang Channel north of Luzon, Growler picked up a contact on its radar. After visual confirmation was obtained, Lt. Cmdr. Thomas B. Oakley, the boat’s new commander, decided to “attack after moonset.” As the submarine continued to stalk the convoy, Growler sent a spread of six torpedoes into the 1,920-ton Japanese tanker Katori Maru, causing a “column of black smoke and flame” that reached a height of 700 feet.

Following the success of this patrol, Growler would go on to conduct two more wolf pack war patrols with different sister submarines, attacking multiple Japanese convoys. On its eleventh and final war patrol, Grower along with USS Hake (SS-256) and USS Hardhead (SS-365), detected an enemy convoy in the South China Sea. Growler closed in for the kill while the other submarines flanked the convoy. Oakley ordered the wolf pack to attack, but that was the last communication ever heard from Growler. A short time later, it was noted in Hake’s war diary that two explosions of “undetermined character” had been heard. Hardhead also heard what sounded like a torpedo explosion followed by three depth charges on the opposite side of the convoy. Hake and Hardhead continued to attack the convoy, sinking the 5,300-ton tanker Manei Maru. Hake endured 16 hours of enemy attacks with some 150 depth charges exploding around it during the battle. After the engagement was complete, the surviving submarines attempted to contact Growler continuously for three days, but to no avail.

On Feb. 1, 1945, Navy Department Communique No. 572 stated, “Growler is overdue from patrol and presumed lost, cause unknown.” All hands, 86 crewmembers including Oakley, were lost. Over the course of the war, Growler sank 15 enemy vessels for a total of 74,900 tons and damaged seven other vessels for 34,100 tons.

Remember the Maine: 125 Years Ago

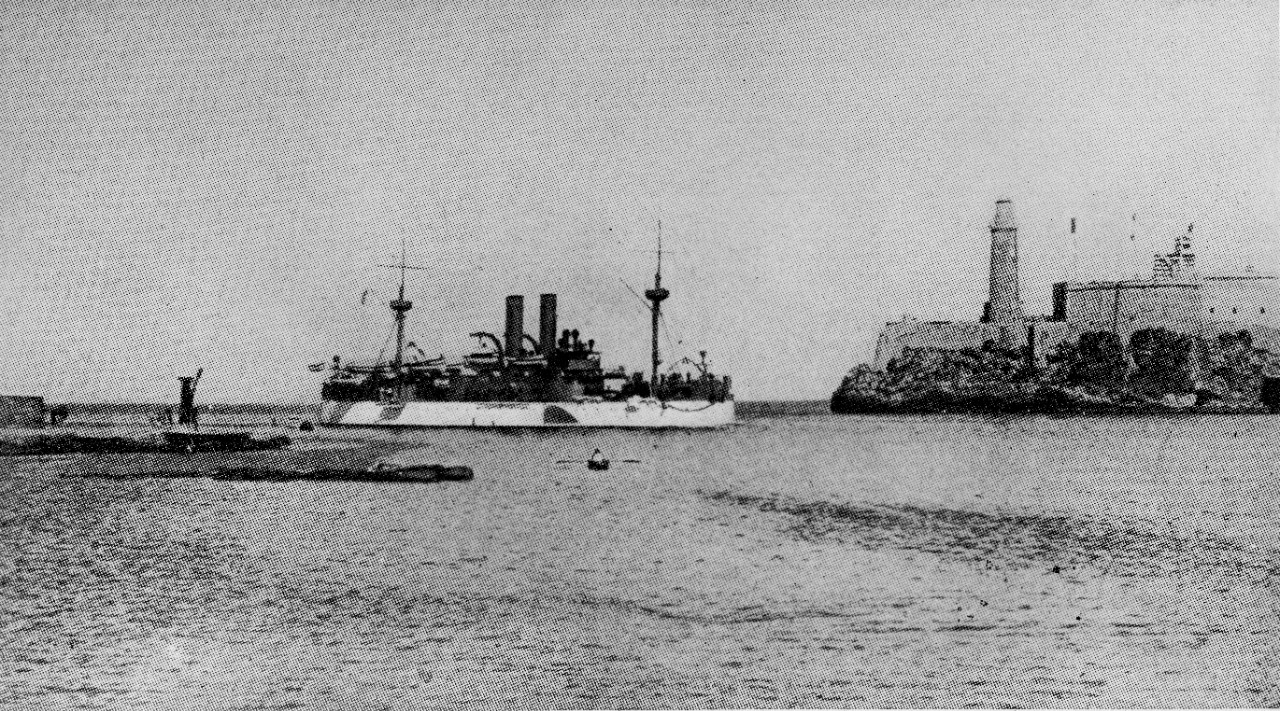

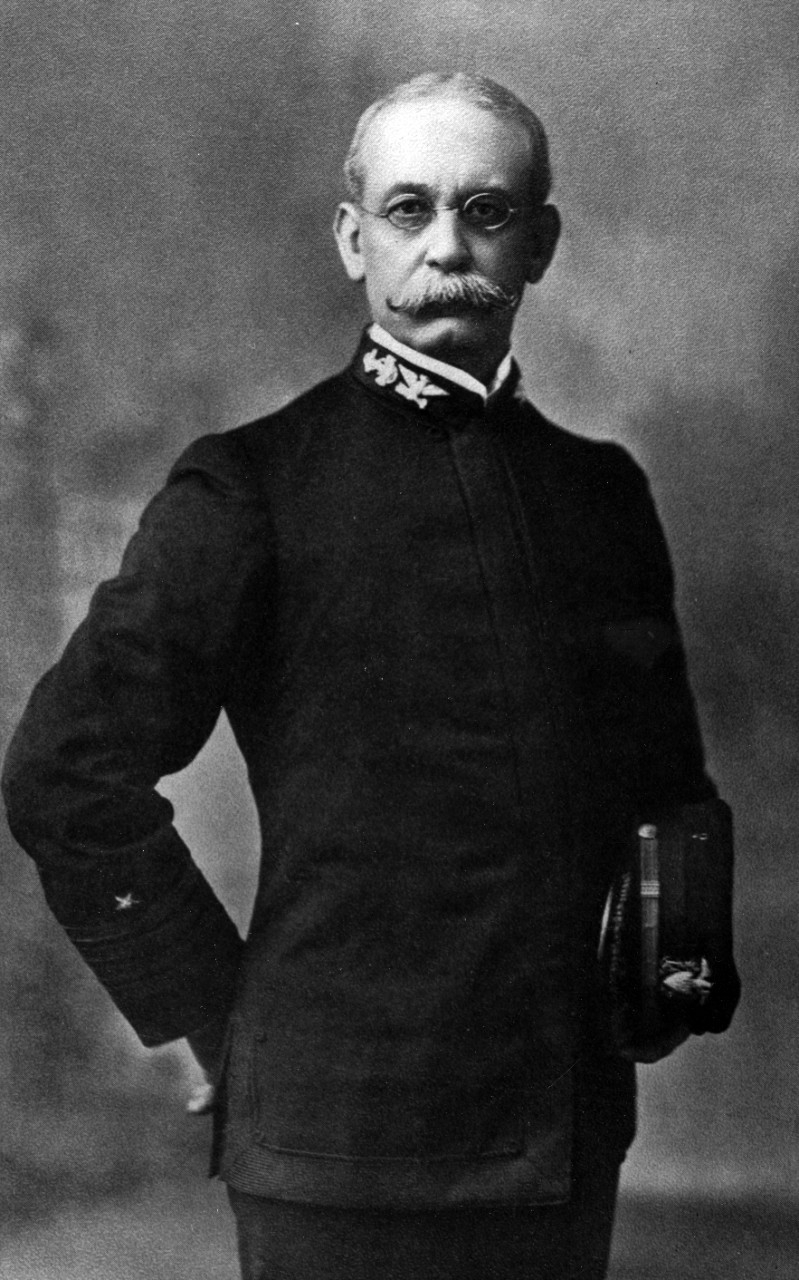

At 9:40 p.m. on Feb. 15, 1898, a massive explosion on board battleship Maine shattered the stillness of Havana Harbor, Cuba. Five tons of powder charges for the vessel’s six- and ten-inch guns ignited, virtually obliterating the forward third of the ship. Most of Maine's crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters in the forward part of the ship when the explosion occurred. Two hundred and sixty-six men lost their lives because of the disaster: 260 died in the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries. Capt. Charles Sigsbee, Maine’s commanding officer, and most of the officers survived because their quarters were located toward the stern of the ship. It was a critical event on the road to the Spanish-American War.

At the time that Maine had arrived in Havana Harbor in January 1898, Spain had already been fighting pro-independence insurgents for three years. Washington had become extremely concerned for the safety of American citizens on the island. President William McKinley’s administration believed that some means of protecting U.S. citizens should be on hand. On Jan. 24, McKinley sent Maine from Key West, Florida, to Havana, after clearing the visit with a reluctant Spanish government. A day later, Maine arrived in Havana Harbor. Spanish authorities in Havana were wary of American intentions, but they afforded Sigsbee and the officers of Maine every courtesy. In order to avoid any possibility of trouble, Maine’s commanding officer did not allow his enlisted men to go on shore. Sigsbee and the U.S. consul at Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, reported that the Navy’s presence appeared to have a calming effect on the situation, and both recommended that the Navy send another battleship to Havana when it came time to relieve Maine.

Then, the tragic event of Feb. 15 took place. The U.S. Navy Department immediately formed a board of inquiry to determine the reason for Maine's destruction. The inquiry, conducted in Havana, lasted four weeks. The condition of the submerged wreck and the lack of technical expertise prevented the board from being as thorough as were later investigations. In the end, they concluded that a mine had detonated under the ship. When the Navy’s verdict was announced, the American public reacted with predictable outrage. Fed by inflammatory articles in the press blaming Spain for the disaster, the public had already placed guilt on the Spanish government. Although McKinley continued to press for a diplomatic settlement to the Cuban problem, he accelerated military preparations. The Spanish position on Cuban independence hardened, and McKinley asked Congress on April 11 for permission to intervene in the conflict. On April 21, the president ordered the Navy to begin a blockade of Cuba, and Spain followed with a declaration of war on April 23. Congress responded with a formal declaration of war on April 25.

The destruction of Maine did not cause the United States to declare war on Spain, but it served as a catalyst. In addition, the sinking of the ship and deaths of U.S. Sailors rallied American opinion more strongly behind armed intervention. Although the war was short in duration, it was costly for Spain. The country had to cede Cuba (which was administered by the U.S. until 1902), Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States in return for $20 million to cover infrastructure costs. The United States, on the other hand, emerged from the war a world power with far-flung overseas possessions and a new stake in international politics that would soon lead it to play a decisive role in the affairs of Europe and the rest of the world.

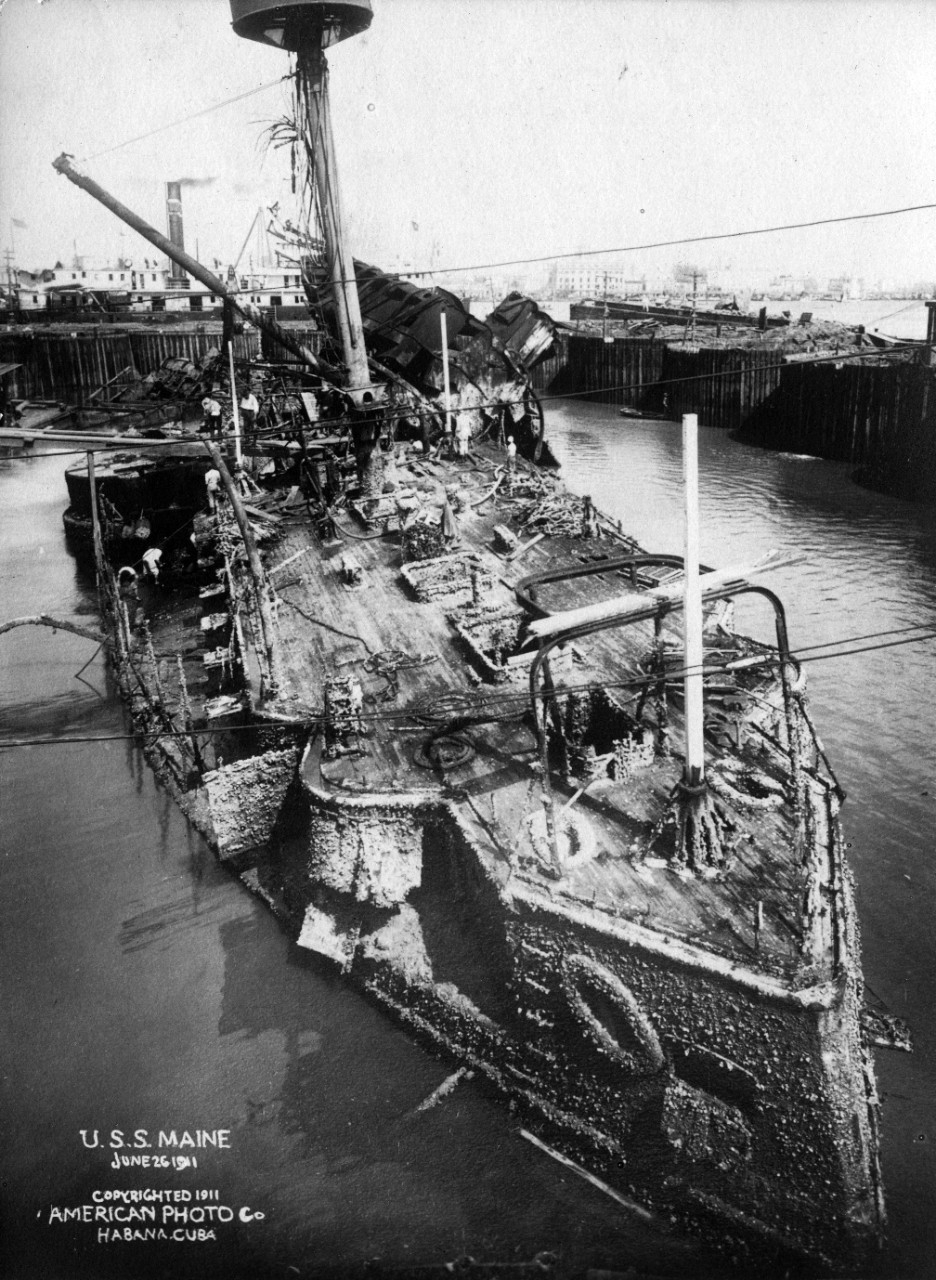

In 1911, the Navy Department ordered a second board of inquiry after Congress approved funds for the removal of the wreck of Maine from Havana Harbor. U.S. Army engineers built a cofferdam around the sunken battleship, thus exposing it, and giving naval investigators an opportunity to examine and photograph the wreckage in detail. Finding the bottom hull plates in the area of the reserve six-inch magazine bent inward and back, the 1911 board also concluded that a mine had detonated under the magazine, causing the explosion that destroyed the ship.

Technical experts at the time of both investigations disagreed with the findings, believing that spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker adjacent to the reserve six-inch magazine was the most likely cause of the explosion on board the ship. In 1976, Adm. Hyman G. Rickover published his book How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed. The admiral had become interested in the disaster and wondered if the application of modern scientific knowledge could determine the cause. He called on two experts on explosions and their effects on ship hulls. Using documentation gathered from the two official inquiries, as well as information on the construction and ammunition of Maine, the experts concluded that the damage caused to the ship was inconsistent with the external explosion of a mine. The most likely cause, they speculated, was spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker next to the magazine.

Some historians have disputed the findings in Rickover’s book, maintaining that failure to detect spontaneous combustion in the coal bunker was highly unlikely. Yet evidence of a mine remains thin, and such theories are based primarily on conjecture. Despite the best efforts of experts and historians in investigating this complex and technical subject, a definitive explanation for the sinking of Maine remains elusive. There is a Maine memorial (the actual ship’s main mast) on display at Arlington National Cemetery. On Feb. 15, there is a scheduled wreath laying at the memorial.

Battle of Iwo Jima

On Feb. 19, 1945, following only a few days of intermittent pre-invasion naval gunfire and aerial bombardment (other than occasional Allied naval bombardments since June 1944), U.S. Marines from the 4th and 5th Divisions landed on the mountainous volcanic island of Iwo Jima. Originally conceived as a brief operation by U.S. commanders, the Battle of Iwo Jima would be one of the bloodiest battles in U.S. history and last five tumultuous weeks, costing the lives of almost 7,000 U.S. service members. Located just 750 miles from Japan’s coast, Iwo Jima was projected to be a U.S. Army Air Forces base for escort fighters and an emergency landing strip for damaged bombers returning from raids on Japan. However, some 21,000 dug-in Japanese army troops awaited the invasion. Japan’s leadership knew they could no longer stop the momentum of the Allied push across the Pacific. They accordingly adjusted their defensive tactics to inflict as much damage and as many casualties as possible in order to undermine the will of Allied forces and civilian societies to continue prosecuting the war.

Once the Marines hit the beaches of Iwo Jima, unexpected and accurate artillery and mortar fire blasted the initial landing wave. In addition, unstable beaches composed of steep terraces of constantly shifting black sand, volcanic cinders, and ash complicated the initial invasion. Tracked vehicles, amphibious tractors, tanks, and supplies were hampered by the rough terrain, causing pile-ups at the waterline as well. Nonetheless, the landings were initially successful under the cover of naval gunfire barrage and close air support mainly provided by Fifth Fleet’s escort carriers. The 5th Marine Division pushed to the northwestern shore within 90 minutes to isolate Mount Suribachi, on Iwo Jima’s southern tip, and the 4th Marine Division advanced toward the airfields. By the end of the first day, 30,000 Marines had landed on the shores of Iwo Jima, but casualties were heavy due to the artillery fire and fanatically held Japanese positions that had to be overcome one by one.

Third Marine Division landed on the operation’s second day. Within several days of the initial invasion, some 70,000 Marines had landed on Iwo Jima. The Japanese suffered heavy losses and ran low on supplies. They mounted most of their counterattacks under the cover of darkness. Although the Japanese tactics were effective, the fall of Iwo Jima was inevitable. Just four days into the fighting, U.S. Marines captured Mount Suribachi, famously raising an American flag at the summit. That image, the second flag raising of the day (the first flag was from USS Missoula, but was deemed too small for American forces to see it across the island), was captured by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal. He won a Pulitzer Prize for the iconic image.

However, the fighting was far from over. Battles raged on in the northern part of Iwo Jima for weeks. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, commander of the Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, even set up a garrison in the northern mountains and mounted a final, 330-man banzai attack on March 25. American forces suffered a number of casualties during the attack, but Iwo Jima was finally declared secure the following day. However, U.S. forces spent many additional weeks trudging through the churned-up terrain finding or killing holdouts who refused to stop fighting or be captured. Dozens of Americans were killed in the process of clearing the island. In fact, two of the Japanese holdouts were so stubborn they continued to hide in the island’s caves, scavenging food and supplies until they finally surrendered in 1949, almost four years after the end of World War II.

In the end, of the 21,000 Japanese troops stationed on Iwo Jima, only 200 were captured. Many Japanese soldiers resorted to suicide rather than become prisoners of war. In addition, Iwo Jima was never used as an air base to support the bombing campaign against Japan. However, Navy Seabees did rebuild the airfields for pilots to use in case of emergency landings. Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander of Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, noted after the battle that “uncommon valor was a common virtue.” Twenty-two U.S. Marines and five Sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroism on Iwo Jima, 14 posthumously.

Butch O’Hare: First Ace of World War II

On Feb. 20, 1942, Lt. Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare in his F4F Wildcat fighter shot down five Japanese bombers and severely damaged a sixth in a single sortie while protecting USS Lexington (CV-2) about 500 miles northeast of Rabaul, New Britain. In all, Lexington’s Fighting Squadron 3 (VF-3) and the ship’s antiaircraft decimated two waves (nine aircraft each) of Japanese Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers during the engagement. O’Hare would be awarded the Medal of Honor on April 12, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and promoted to lieutenant commander by order of the president for his actions on that day.

During the enemy attack, VF-3 maneuvered to take on the incoming bombers. Although VF-3 was composed of highly trained naval aviators, this was their first combat operation. One section of Wildcats, under the command of VF-3’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. John Thach, attacked nine of the incoming Betty bombers, shooting down three of them and driving the rest away. However, while Thach’s group was attacking one part of the Japanese force, another section of Betty bombers headed for Lexington from the opposite direction. As the bombers dived to attack the carrier, only two Wildcats were in their way—those piloted by Lt. Marion Dufilho and O’Hare. The four Browning .50-caliber machine guns on Dufilho’s Wildcat jammed, leaving O’Hare’s as the only plane that could interdict the oncoming Japanese force. O’Hare maneuvered his Wildcat above the Japanese bombers and dove down on the formation. As the Bettys flew toward Lexington, O’Hare made a series of slashing passes, downing the enemy aircraft one by one. The bombers that did make it through O’Hare’s attacks and Lexington’s antiaircraft fire dropped 250-kilogram bombs astern of the carrier, but no damage was inflicted on the ship.

After landing back aboard Lexington, O’Hare claimed that he had shot down six of the bombers during the attack. He was ultimately credited with five kills. No matter the score, it was clear to all that day that O’Hare’s solo attacks had broken up the Japanese formation and saved Lexington. As the first American ace of World War II, O’Hare became a household name and was just what the nation needed in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack. Unfortunately, O’Hare did not survive the war. On Nov. 27, 1943, as he flew an F6F Hellcat in night combat near Tarawa Atoll, O’Hare’s plane, possibly caught in the U.S.–Japanese crossfire, went down over the dark waters. His body was never recovered.

O’Hare grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and his father was determined to instill some discipline into his son, enrolling him at the Western Military Academy in 1927. While O’Hare proved to be just an average football player, he demonstrated excellent marksmanship skills on the academy’s rifle team. Determined that his son would avoid his own often-shady law practice, O’Hare’s father urged him to apply to the United States Naval Academy. O’Hare failed to pass the entrance exam, but after attending a prep school, was accepted on his second try and would graduate in 1937. Nicknamed “Butch” by his classmates, O’Hare served on battleships before being accepted into the Navy’s flight program in 1939. Earning his Navy wings of gold, O’Hare was assigned to Lexington’s VF-3. Today, O’Hare is best known for his namesake, Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, one of the busiest airports in the world. The destroyer USS O’Hare (DD-889) was also named in his honor.