Growler III (SS-215)

1942-1944

A large-mouth black bass.

III

(SS-215: displacement 1,526 (surface) 2,424 (submerged); length 311'9"; beam 27'2"; draft 15'3"; speed 20 knots (surface); 8.5 knots (submerged); complement 66; armament 1 3-inch, 1 .50 caliber machine gun, 10 (six forward, four aft) 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Gato)

The third Growler (SS-215) was laid down on 10 February 1941 at Groton, Conn., by the Electric Boat Co.; launched on 22 November 1941; sponsored by Mrs. Robert L. Ghormley; and commissioned on 20 March 1942, Lt. Cmdr. Howard W. Gilmore in command.

Sailing out of Groton to conduct her first sea trials on 23 March 1942, Growler made a series of Condition II dives and operated her engineering plant at full speed. She returned to her builders’ yard to have the “night shift repair minor defects and leaks.” The next day, she reported for duty to Adm. Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet (ComInch), and Vice Adm. Royal E. Ingersoll, C-in-C, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CinCLant). For the rest of the month of March, Growler continued to conduct intensive training for her crew at sea, and returned at night to Groton for minor repairs.

On 1 April 1942, Growler participated with the submarine rescue vessel Falcon (ASR-2) to conduct various drills and training, including torpedo and night approaches as a part of Task Force (TF) 25.6, New Construction Submarines, operating under Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Operating in the Submarine Sanctuary off New London, Conn., she continued her commissioning and training underway. The next day the No. 8 torpedo tube’s outer door and shutter malfunctioned due to an indeterminate cause while conducting torpedo approaches with Falcon. On 3 April, Growler docked in the Marine Railway, Electric Boat Co., for repairs to her No. 8 torpedo tube. During the course of repair, the workers discovered three of her starboard propeller blades were bent. Over the next few days, the shipyard workers repaired her starboard propeller, fixed the shutter and door on the No. 8 torpedo tube, and checked and cleaned her other torpedo tubes as well.

Proceeding to the Naval Torpedo Station, Newport, R.I., on 8 April 1942, Growler loaded fourteen Mk. XIV-1 torpedoes, spare parts, and accessories as approved by the Bureau of Ordnance. With her torpedo tubes now full, she prepared to get underway when Vice Adm. Ingersoll made an informal inspection of the submarine. On 9 April, she made way to New London and continued contract torpedo firing and afterwards, brought on board ten more torpedoes. Over the course of the next few days, Growler operated out of New London, conducting drills and installed radar shielding in accordance with instructions of the Bureau of Ships. Provisions and stores brought on board, she then operated with the coastal yacht Sapphire (PYc-2), conducting torpedo approaches on 14 April.

After firing several torpedoes and completing a successful deep dive with passengers from the Bureau of Ships and Submarine Base, New London, on board to conduct radar tests on 17 April 1942, Growler faltered after an unsuccessful attempt to conduct four hour full power runs. Things went from bad to worse when the boat developed minor engine problems which may have contributed to failing the power runs. Repairs were made at sea, and after calibrations to her DQ direction finder, she operated with Finback (SS-230), Grunion (SS-216), and O-10 (SS-71) before returning to New London’s State Pier on 19 April 1942. Two days later, all four boats operated with Army Air Force planes from Springfield, Mass., to practice day and nighttime operations. A successful four hour full power trial was conducted on 22 April, before Growler returned to Electric Boat’s Marine Railway for emergency repairs to her safety tank flood valves (after a gasket blew out) on 24 April. She spent the next few days in dry dock, before getting underway to conduct night approaches, with Sapphire acting as the target. By the last day of April, after running through more drills and night approaches, Growler conducted low visibility surprise attacks during the day, operating with Finback and Sapphire.

Growler returned to New London for upkeep prior to her departure for Hawaii on 1 May 1942. Three days later, after being degaussed and assigned to Task Unit (TU) 25.6.6, she got underway for Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal. On 12 May, she arrived at her rendezvous station 52 miles from the Colon Breakwater, while being escorted by the motor torpedo boat tender Niagara (PG-52) to Coco Solo.

Clearing Balboa, Canal Zone, on 15 May 1942, Growler received her new assignment to TU 7.8.2, and arrived in Pearl Harbor on 31 May, escorted to the submarine base by Litchfield (DD-336). The following day, she commenced a period of training and special availability. The special training and availability period concluded on 19 June, and she departed Pearl Harbor for Midway the next day, conducting daily training dives and drills en route.

Growler’s first war patrol began on 29 June 1942, after Task Force 8 sent orders assigning her a patrol area in the Aleutians. After refueling and charging torpedoes at Midway, she arrived at her assigned area on 30 June, patrolling Kiska Harbor. Sighting what Lt. Cmdr. Gilmore believed at first were three cruisers leaving Kiska on 5 July, Growler closed for a submerged torpedo attack and then surfaced. The enemy ships proved to be destroyers, and she “approached DD’s at slow speed, silent running in case they were maintaining sound watch.” Firing a spread of torpedoes, one each struck the Asashio-class Kasumi, and the Kagero-class Shiranui, severing her bow and killing three men. Both enemy destroyers suffered severe damage that left them unable to fight back.

Growler next fired two torpedoes at the third destroyer, Arare. While the first torpedo missed, the second struck her amidships. By sonar and by ear, Growler’s crew heard three heavy explosions and “53 lighter ones.” Lashing out at her attacker, Arare managed to fire off two torpedoes in desperation. As the Japanese torpedoes "swished down each side" of Growler, she dived deep, but no depth charges followed. Arare sank, taking 140 men down with her. The badly damaged Shiranui managed to rescue Cmdr. Ogata Tomoe, Arare’s commanding officer, and 42 survivors. After escaping a short depth charge attack the day after striking the Japanese, Growler put in at Dutch Harbor for an inspection and light repairs on 9 July. She departed Dutch Harbor on 11 July, and completed her successful patrol without finding any more targets. Escorted by Tracy (DM-19), Growler berthed at Pearl Harbor on 17 July.

On 5 August 1942, Growler began her second war patrol. Getting underway from Pearl Harbor, she steamed for Midway. Arriving on 9 August, she took on fuel, and proceeded to her patrol area off Taiwan. She conducted drills for the next couple of weeks while she maintained course for Taiwan. On 23 August, she made a night attack on an enemy freighter while submerged, surfacing only after both torpedoes ran under the target and failed to explode. The freighter turned and made for shallow water, escaping any follow-up attack. Turning south, Growler ran through a fishing fleet of some 100 – 150 boats that stayed nearby for the next three hours. At 0730 on 25 August, she sighted a 10,000-ton passenger freighter. Growler passed just under the large fishing fleet to track the enemy ship, and fired a spread of three torpedoes from a range of 2,500 yards. All three missed the freighter due to “Size of target and over anxiousness.” The Japanese vessel blindly fired two of her guns in response, missing Growler completely. Growler continued to track the freighter until three large sampans, acting as escorts, bore down. Gilmore ordered evasive maneuvers just as an intense depth charge attack began. Over the next three hours, some 65 “ash cans” were dropped, prompting a sailor at the bow plane station to become “hysterical.” Given a shot of morphine, the man regained his composure three days later, and resumed watch-standing duties in six.

Spotlighting his dash and audacity, Cmdr. Gilmore managed to attack the 2,904-ton ex-gunboat Senyo Maru, despite being depth-charged. After firing a total of four torpedoes, Growler scored two hits, sinking her by the bow. As no further enemy vessels appeared in the area after three more days of running deep, she moved to the east. Eifuku Maru, a 5,866-ton cargo ship, became her second victim during a submerged attack on 31 August 1942. Firing two torpedoes at a range of only 1,000 yards, Growler scored two hits, and remained nearby while the vessel sank in 90 seconds.

At 0400 on 4 September 1942, Growler put a “darkened sampan” out of action, expending six rounds of fifty-caliber machinegun fire. Nearly four hours later, lookouts sighted masts of a large ship and submerged. Mistakenly identifying the enemy vessel as Itukusima, Cmdr. Gilmore ordered two torpedoes fired. The 4,000-ton supply ship Kashino suffered hits to her bridge, while a third torpedo missed, and a fourth found its mark, sinking the ammunition-laden vessel in just two minutes. On 7 September, Growler sent two torpedoes into the 2,204-ton cargo ship Taika Maru, which broke in half and also sank in only two minutes. Over the next few days, the Japanese sent more patrols out to find Growler. Cmdr. Gilmore ordered the ship underway to patrol the Pescadores Channel on 11 September. Two days later, Growler observed a scattered convoy consisting of seven freighters and one destroyer of the Momo-class. Firing four torpedoes into the convoy at 850 yards, her crew heard two explosions, but “when observed three minutes after firing target was apparently undamaged.” Shortly after launching her torpedoes at the enemy ships, patrol boats sped towards Growler. Not wanting to engage in a potentially deadly surface duel, she dived to periscope depth to evade her foes. On 18 September, while still patrolling in the channel, she sighted the Hikawa Maru, a hospital ship that was “properly marked,” and proceeded on course.

Five days later, Growler cleared her patrol area, and arrived safely back at Midway on 23 September 1942. A letter from Commander Submarine Squadron (ComSubRon) 8, dated 24 September 1942, commended Cmdr. Gilmore for “a very aggressive second war patrol.” Growler achieved a score of 33.3% hits of the torpedoes fired at enemy vessels. While a “creditable and above average performance,” ComSubRon 8 critiqued “it is to be regretted that Growler having repeatedly aggressively gained extremely favorable firing position, could not have attained an even higher percentage of hits.”

Growler arrived in Pearl Harbor on 30 September 1942, and commenced refit on 1 October. While in the yard she had one propeller replaced, and an SJ radar and 20 millimeter gun installed. Declared ready for sea after one full day of training on 21 October, Growler left for her third war patrol the next day. Escorted out of Pearl Harbor by Tarpon (SS-175), she steamed southward and received her area assignment on 26 October. Continuing on the surface until she passed within 20 miles of Tanga Island, Cmdr. Gilmore decided to cover the East Cape to Truk route. From this area, all probable lanes of Japanese movement between Rabaul and Truk were covered. From 3 – 16 November, Growler maintained patrol within the sea lanes of this area. On the night of 11 November, lights were observed on Tanga Island, and the skipper believed the Japanese “might be engaged in construction work on this island.” But a closer inspection of coves and the shoreline around Tanga from a range of 3,000 yards revealed nothing.

On 20 November 1942, Growler received a message stating enemy submarines and destroyers were en route to Rabaul. An estimation of the times of transit through her patrol area had the Japanese vessels arriving two days hence. Cmdr. Gilmore planned to cover the routes in the Solomon Islands off Truk. He worried that crossing south of the area would expose Growler to enemy mines and “intensive air and surface” patrols. Patrolling the waters off Kavieng on 25 November, Growler approached an enemy destroyer of the Amagiri-class, before the skipper halted her attack for unspecified reasons. On 26 November, she sighted the 6,440-ton Yamazuki Maru, but determined an attack was not possible. Later in the day, an enemy freighter and destroyer of the Momo-class were sighted, but again, Cmdr. Gilmore found himself out of position and range for an attack run. Originally ordered to return to base on 3 December, Growler extended her run until 10 December, when she moored in Brisbane, Australia. Two days prior to her arrival, she suffered a casualty in her No. 2 main engine and remained out of commission until a broken crankshaft could be replaced, completing a refit on 31 December.

On New Year’s Day 1943, Growler departed Brisbane for her fourth war patrol. While steaming to her patrol station off Rabaul the very next day, she sighted signal lights from three contacts on 9 January. At 0127, while closing on these vessels, a flare burst overhead causing Cmdr. Gilmore to order the bridge cleared so Growler could dive. An hour-and-a-half later, she surfaced and almost immediately spotted another flare burst. The skipper assumed the flares were launched from Japanese aircraft searching for American submarines. Almost a week later, on 16 January, Growler scored two hits on the lead ship of an enemy convoy. The 5,857-ton cargo ship Chifuki Maru listed heavily to port before going down by her stern. Increasing her speed to escape the enemy’s counterattack, Growler ran a gauntlet of depth charges and bombs, unleashed by nearby Japanese destroyers and aircraft. Cmdr. Gilmore ordered Growler into a deep dive and surfaced only when he was sure ship and crew were safe from their pursuers.

Three days later, on 19 January 1943, Growler “decided to patrol off coast of New Ireland.” After receiving a message regarding the location of a 4,000-ton enemy cargo vessel and submarine chaser escort, the skipper ordered a change of course to Cape Watui in hopes of laying an ambush for the Japanese. Due to poor visibility, Cmdr. Gilmore called off the ambuscade, while Growler ran on the surface. Receiving a new assignment on 22 January to guard the northward approaches towards Rabaul, where heavy enemy traffic reportedly sailed unchallenged, Growler made way.

After identifying an enemy cargo steamer on 30 January 1943, Growler tracked the zig-zagging vessel and at a range of 2,000 yards fired three “fish.” After all missed, the Japanese opened up with gunfire. Cmdr. Gilmore readjusted and fired a single torpedo which struck the steamer’s bow. The damaged enemy ship launched three depth charges in response, landing far from her predator. Diving deep, Growler escaped two closer depth charges and broke off contact with the Maru. It was believed the Japanese vessel may have continued on to Kavieng to repair her damaged bow.

Proceeding towards Hermit Island to establish a new patrol of enemy traffic sailing for Truk, Growler tracked a converted gunboat. Firing one torpedo at a range of 800 yards, Cmdr. Gilmore watched from the periscope as the torpedo ran under the target. Bemusedly, he observed Japanese sailors “watch it run under their ship.” Immediately, the gunboat swung towards her attacker and dropped two depth charges which missed. Silently, Growler slipped beneath the waves to avoid any further depth charges, and set course back towards Rabaul.

Settling into a normal week of routine patrolling, a small enemy ship was sighted off Growler’s starboard bow on 7 February 1943. Swinging around, Growler made her torpedo tubes ready for a surface attack. The 900-ton stores ship Hayasaki sighted the boat and reversed course to attack, making ready to ram. Gilmore ordered left full rudder, sounded the collision alarm, and rammed the enemy vessel at a speed of 17 knots. Striking the enemy head-on between bow and bridge, Growler’s crew was violently tossed around, with one sailor recalling that “the impact was terrific, knocking everyone down.”

Hayasaki immediately opened fire with machine guns, mortally wounding Cmdr. Gilmore, and killing Ens. William W. Williams, the Junior Officer of the Deck, and lookout F3c Wilbert F. Kelley, on the bridge. An immediate order to “clear the bridge,” sent Lt. Cmdr. Arnold F. Schade, Growler’s executive officer, and the quartermaster below, pulling two wounded men -- TM3c John A. Baxley and GM3c George Wade -- through the hatch behind them. Cmdr. Gilmore, realizing he endangered ship and crew by his inability to get below decks in time, then uttered the legendary words: “Take her down.” After the briefest of hesitations and with a heavy heart, Lt. Cmdr. Schade followed his commanding officer’s last order and closed the hatch. The Japanese “continued spraying the bridge with machine gun fire until it was under water.” For his heroic sacrifice, Cmdr. Gilmore was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the first of seven U.S. submarine commanders so honored during the war.

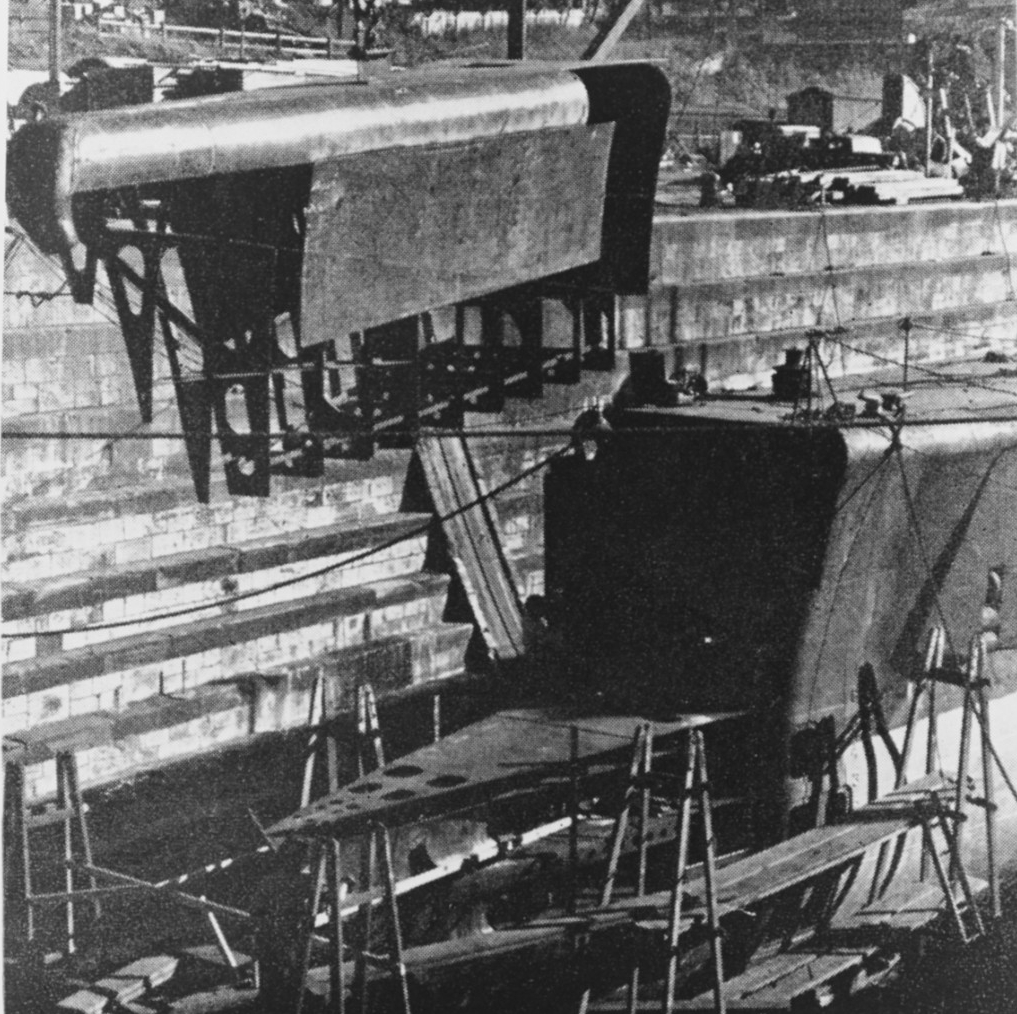

After the loss of their beloved skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Schade “whose resourcefulness and leadership” were responsible for Growler’s safe return, ably assumed command. Directed by the task force commander to halt further patrols, she returned to Australia with a severely damaged bow bent 90-degrees to port. Growler moored in Brisbane on 17 February 1943 for extensive repairs by Australian company Evans Deakin Co. Lt. Cmdr. Schade recalled that "When the Australians replaced our damaged bow they put two little kangaroos there - as a sort of figure-head. It is now our most prized distinctive marking." Shortly after the metal kangaroos were attached to the port and starboard sides of her bow, Growler received the nickname “The Kangaroo Express.”

Undocked with most of her new bow complete on 1 May 1943, Growler began test firing dummy torpedoes. Operating from Moreton Bay four days later, she fired exercise torpedoes from the bow tubes. On 6 May, she tested and fired all of her guns. Extensive at-sea training commenced from 7 May – 11 May. On 13 May 1943, Growler got underway for her fifth war patrol.

After an uneventful couple of weeks in the Bismarck-Solomons Sea, Growler tracked an enemy freighter of the Takatiho-class the morning of 4 June, but was unable to close. On 19 January, the 5,196-ton passenger-cargo vessel Miyadono Maru was the second ship in line of a convoy of eight ships and three escorts. Chasing the convoy on the surface, she fired four torpedoes at the lead ship and Miyadono Maru, scoring two hits on each. Noting the sounds of “breaking up and internal explosions heard from the second ship as she sank,” Lt. Cmdr. Schade chalked up his first kill as commanding officer, as well as some measure of vengeance for the death of Cmdr. Gilmore. However, after the larger of the two ships was observed dead in the water and smoking heavily by Guardfish (SS-217), who trailed the convoy for two hours after Growler’s attack, a lack of conclusive evidence for sinking both ships led only to credit for the sinking of Miyadono Maru, the smaller of the two enemy vessels. After a 49-day patrol in the waters off northern New Guinea, Growler returned to Brisbane on 30 June.

The sixth and seventh patrols, following so quickly after the success of Lt. Cmdr. Schade’s first as commanding officer, proved largely uneventful. Getting underway from Brisbane on 21 July 1943, for her sixth war patrol, the Bismarck-Solomons Sea became Growler’s assigned area of operations. A lackluster eight enemy contacts were made during the entire fifty-three day patrol. Two of these were hospital ships while three of the contacts were small vessels considered “unworthy of torpedo attack.” She attacked only one of the Japanese vessels encountered, an armed trawler towing a large loaded barge, unleashing three torpedoes that all missed. The highlight of the patrol seemed to be two memorable experiences with fish native to the Pacific Ocean. The first occurred on 23 August when Growler “ran into school of blackfish. Hit one head on, with severe jar. Ran over him and cut him up with the propellers…a large pool of blood and fish chunks.” The next “fish story” occurred on 6 September when upon surfacing, the crew noticed “the deck covered with large Bonita fish. We collected a large sack full (over fifty) and served fresh fillet to all hands.” Not long after Growler’s fish fry, she returned to Brisbane, arriving there on 12 September.

Marred by trouble with her storage battery and generators, Growler’s seventh war patrol to the Bismarck-Solomons area ended earlier than scheduled. After getting underway on 4 October 1943, she quickly began experiencing material problems that only seemed to get worse as the patrol wore on. Ordered to Pearl Harbor, she arrived in Hawaii on 7 November and from there steamed to Hunter's Point, Calif., mooring in the Navy Yard on 18 November 1943, for an extensive overhaul and refitting. Given holiday leave in shifts, the crew visited with their families while Growler received repairs. Tragedy struck on 20 December 1943, when EMCM Euen M. Jenes perished in a car accident near Riverside, Calif., while home on leave.

Returning to Pearl Harbor on 8 February 1944, Growler departed for Midway, arriving to refuel there on 21 February. Departing for her eighth war patrol to the East China Sea, a typhoon’s high seas and wind delayed her arrival there and knocked an auxiliary engine out of commission for the remainder of her patrol. On 10 March, after finally arriving in her patrol area three days late, Growler was again plagued by violent weather which made even periscope observation almost impossible. After firing four torpedoes at a 3,000-ton enemy freighter on 22 March 1943, the first torpedo’s wake “appeared to pass under the bow; others not seen.” The freighter appeared to absorb a hit by one of the four torpedoes when two Japanese patrol boats suddenly appeared to pinpoint Growler’s location. Lt. Cmdr. Schade gave the order to run deep just as the enemy craft began launching depth charges. After a half-hour of quiet, the skipper started climbing to periscope depth when the depth-charging resumed. Running on the surface, Growler outran her pursuers and surfaced nine miles off the beach near Amami O Shima. She would not experience a small victory until 10 April, after encountering a 250-ton Japanese gunboat patrolling off Io Kita Jima. After tracking the gunboat while submerged, Growler battle surfaced and opened up on the enemy with her 20 millimeter gun, setting the gunboat on fire and sinking him. The war patrol log noted “Throughout the entire patrol, the weather was very stormy, with rough seas. Periscope observations could be made only at high speed.”

Growler returned to Majuro on 16 April 1944, and conducted intensive exercises in the area for almost a month. On 14 May, she departed Majuro under new skipper Lt. Cmdr. Thomas B. Oakley, Jr., to take up patrol in the Marianas-Eastern Philippines-Luzon area for her ninth war patrol. She first began patrolling just off the Marianas, and conducted sweeps of the Saipan-Tinian Island channels prior to the landing of U.S. forces at Saipan on 15 June.

Growler received orders to perform life guard missions and rescue any downed airmen in their area of responsibility during the invasion of Saipan. She later spent a few days guarding Surigao Strait, while also awaiting the return of the Japanese fleet from patrol of the Philippine Sea. On 21 June 1944, while performing a routine patrol off Siargao Island in the Philippines, Cmdr. Oakley received orders to leave the area. One day later, Growler rendezvoused with Bang (SS-385) and Seahorse (SS-304) to form a wolf pack. On 28 June, the pack steamed past Luzon, and Growler surfaced to transit the Balintang Channel. While the three submarines sailed through the channel on a dark overcast night, Growler picked up a pip on her radar. Shortly after visual confirmation of four distinct vessels was relayed to Cmdr. Oakley he “decided to attack after moonset.” Continuing to track the convoy of Japanese ships, she fired a spread of six torpedoes from her bow tubes at 0230. After observing the first hit, and hearing two other detonations, Ens. William K. Carr, “who has witnessed 11 ships sink, observed at least 3 hits on the tanker.” Only four minutes elapsed between the firing of Growler’s torpedoes and the spectacular sinking of the 1,920-ton Japanese tanker Katori Maru. After hearing seven detonations, lookouts onboard Growler watched a “column of black smoke and flame” reach a height of 700-feet. “Streamers of fire shot out in every direction resembling a ‘flower pot’ of July 4th fame.” Ens. Carr watched the “flash and blast of the target exploding,” and felt the shock wave of the fierce detonations. The crew determined the enemy tanker carried gasoline in her holds below deck. Growler’s ninth war patrol report also recorded the probable sinking of a 600-ton escort ship, hit by one of the torpedoes fired in the same spread that sank Katori Maru.

At 0840 on the morning of 6 July 1944, lookouts spotted a raft and maneuvered alongside. Huddled around a rusted drum in the center of the raft were five Japanese “well-dressed in the attire of fishermen.” Their heads covered with a piece of canvas and “playing possum,” three of the men suffered from immersion foot and only one “paid any attention to our hails-he opened his eyes and closed them again.” A second man deliberately threw off a heaving line tossed over by a Growler lookout. All refused to be rescued and “as they were drifting in the general direction of land about 150 miles away: decided to let nature take its course.” Resuming course, Growler steamed on, leaving the stubborn enemy fishermen behind.

A week later, Growler put in for Midway at 0645 and after a quick stop for refueling steamed for Pearl Harbor some nine hours later. On 17 July 1944, she moored at the Submarine Base in Oahu after traveling 12,437 nautical miles during her 65 days of patrol. Growler received the Combat Insignia Award for a successful patrol.

During her refit, Growler had a new 40 millimeter gun installed, plus two .50-caliber machine gun mounts and topside stowage for guns and ammunition. After four days of firing Mk.18 exercise torpedoes off Hawaii, she got underway on 11 August 1944 for Taiwan. While at Midway on 15 August, Growler formed a wolf pack with Sealion (SS-315) and Pampanito (SS-383). Their skippers held a council of war and conferred on their group the nickname “Ben’s Busters” for pack leader Cmdr. Oakley. Hashing out plans and other items of importance during the meeting, daily patrol stations were assigned, rendezvous points agreed upon and communications thoroughly discussed. Two days later, Ben’s Busters departed Midway and advanced at 12 knots for their patrol area off Taiwan. On 31 August 1944, after transiting into the South China Sea, Growler made contact with a twenty-vessel convoy at a distance of 18,000 yards. Two of the larger ships “zigged into a wonderful set-up.” At 0430, Cmdr. Oakley ordered three bow tubes to fire at the nearest tanker, and three more at a freighter. Three of her “fish” struck the 9,181-ton tanker Rikko Maru, forward of her bridge. After his stack exploded, only the stern section remained and “it could not be seen later.” The freighter also suffered two hits, both aft of her stack. With a “bone in his teeth” and “firing everything at us,” a Japanese destroyer sighted Growler and gave chase, furiously launching depth charges while dangerously firing 40 millimeter gunfire at his own convoy.

At 0442, Growler commenced firing two torpedoes from her stern tubes in response at the “destroyer” (which turned out to be an unidentified escort-type vessel). One of her torpedoes struck the enemy vessel and “his lights went out, sparks flew in all directions and a huge puff of black smoke shot up.” Two more explosions in rapid succession were heard, and suddenly, the Japanese ship disappeared from both view and radar. “We sure shoved that bone in his teeth down his throat!” a crewman later remembered. In mass confusion, several of the remaining ships in the enemy convoy “are shooting at each other,” and only a single enemy patrol craft “now the only thing chasing us” was firing on Growler. Deciding to break contact because of the approaching dawn and the possibility of being spotted by Japanese aircraft, Cmdr. Oakley ordered Growler down and made her escape. She later shared credit for damaging the 9,181-ton tanker Rikko Maru with Sealion.

After routine patrolling off Taiwan for the next couple of weeks, the wolf pack entered the Luzon Strait and sighted a convoy of eight enemy ships on 12 September 1944. In attacks on two separate convoys that day, Growler expended 23 torpedoes. The first action began with an attack on a large convoy that split up following an attack by Sealion. At 0201 Growler fired three torpedoes from her bow tubes and struck 860-ton coast defense vessel Hirato abaft her stack with the first shot. The other two torpedoes struck shortly after, and “a column of smoke was seen between the bridge and the stack of the split superstructures.” Rear Adm. Kajioka Sadamichi, who had commanded multiple amphibious operations earlier in the war, including the initial assault on Wake Island that had met heavy resistance, went down with his flagship Hirato, as did 106 of her sailors.

As Hirato slipped beneath the sea, Japanese destroyer Shikinami sighted Growler running on the surface and turned to attack. Cmdr. Oakley calmly fired a spread of three torpedoes at her from a range of 1,150 yards, observing one explosion light up the night sky. Blazing furiously, the 1,950-ton Fubuki-class destroyer listed 70° to port. As Oakley watched the Japanese sailors clambering onto the deck, bridge and foremast, he exclaimed: “He is now at radar depth commencing his approach, on Davey Jones’ Locker!” Shikinami sank in ten minutes, taking 128 of her 219 sailors with her, including Lt. Cmdr. Takahashi Tatsuhiko, her commanding officer.

At 0531, Lt. Cmdr. Eli T. Reich’s Sealion torpedoed Rakuyo Maru, a cargo ship used as a prison ship. Part of convoy HI-72 carrying Allied prisoners of war from Singapore to Japan, Rakuyo Maru stayed afloat for another 13 hours before sinking at 1830. Approximately 1,318 Australian, British, and American POWs abandoned ship. In the chaos that followed, several of the Allied prisoners took revenge on their Japanese captors, overpowering and killing several guards. Some 1,159 of the Allied POWs died, most by drowning, although the Japanese shot, stabbed, or bayoneted several of the unfortunate men.

At 2254, Pampanito (Lt. Cmdr. Paul E. Summers, commanding) sank the transport Kachidoki Maru with 950 Allied POWs on board. Sinking three minutes later, 12 Japanese sailors and 476 passengers (including 431 POWs) perished in the loss. Pampanito also sank Zuiho Maru with no survivors. Japanese ships rescued some of the POWs from the sea, and the survivors were transferred to Kibitsu Maru before being taken to Japan and used as slave labor. The wolf pack returned to the scene three days later and rescued 159 American and British survivors (92 Americans and 67 British). Seven of the newly released POWs died en route to Saipan.

In the attack on the two convoys of 31 August and 12 September 1944, Growler sank a tanker, freighter, unidentified escort type vessel, as well as Hirato and Shikinami. She also managed to damage two more freighters despite rough seas caused by an approaching typhoon, making the destruction of the enemy ships that much more impressive. Growler’s crew paid tribute for a highly successful war patrol to Neptunus Rex and his Royal Party when they crossed the Equator on 19 September 1944. Thirty-eight Pollywogs were initiated into the Ancient Order of the Deep. The war patrol report states, rather seriously, that there were “no casualties” amongst the crew during the time-honored, and occasionally violent, naval ritual. Three days later the Shellbacks of Growler entered the Indian Ocean, and on 26 September moored at Fremantle. Awarded the Combat Insignia Award for the seventh time in her career, Growler had a short refit and conducted training exercises off Australia.

Departing from Fremantle on 20 October 1944 for her eleventh and final war patrol, Growler led another wolf pack under the command of Cmdr. Oakley, this time with Hake (SS-256) and Hardhead (SS-365). Steaming for the South China Sea, the wolf pack were assigned operations as a search and attack group. A slight malfunction with her SJ radar on 7 November became serious enough for Growler to contact Bream (SS-243) and request a future rendezvous to receive spare parts to fix the problem. On 8 November, her radar still functional, Growler and her pack followed an enemy convoy and closed for an attack. Hake and Hardhead were both on the opposite side of the convoy, and received an order from Cmdr. Oakley to attack, with Hardhead to maintain position off the convoy’s port bow. It was the last communication ever received from Growler. A short time later, Hake noted in her war diary that she heard two explosions of undetermined character, and almost simultaneously, the convoy zigged away from Growler’s position. Hardhead heard what sounded like a torpedo explosion followed by three depth charges on the opposite side of the convoy.

Complying with Cmdr. Oakley’s last orders, Hardhead swiftly went into action and sank the 5,300-ton tanker Manei Maru with three well-placed shots. Immediately after, she suffered a heavy depth-charge counterattack from the convoy’s escorts. Hake watched the tanker sink, quickly diving deep herself to avoid an onslaught that kept her on the bottom for nearly sixteen hours with some 150 depth charges exploding all around her. After surviving the murderous barrage, Hake and Hardhead attempted to contact Growler without success for the next three days. She also never made her rendezvous with Bream. The likely culprits of Growler’s ultimate destruction were later identified as Japanese destroyer Shigure, escort vessel Chiburi, or Kaibokan [Coast Defense Vessel] No. 19. The possibility also exists, however unlikely, that one of Growler’s own torpedoes made a premature or circular run, such as occurred in the cases of Tullibee (SS-284) and Tang (SS-306).

Navy Department Communique No. 572, dated 1 February 1945, states: “Growler is overdue from patrol and presumed lost, cause unknown” and that the next-of-kin of her officers and crew had been informed. All hands, 86 souls, including Cdr. Oakley, were lost.

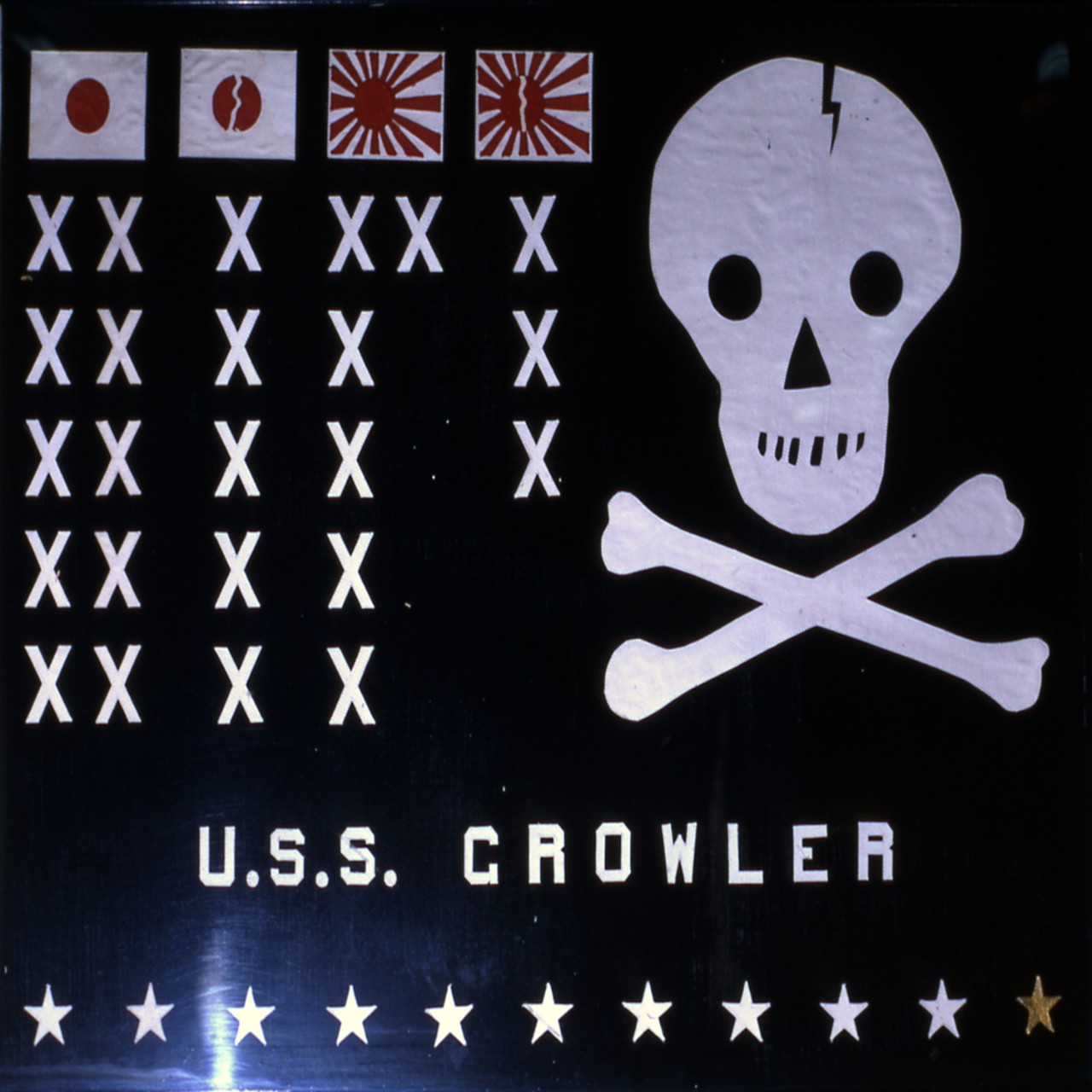

Growler had sunk 15 enemy vessels for a total of 74,900 tons, and damaged 7 others for 34,100 tons. She was stricken from the Navy Register on 8 February 1945.

Famed director John Huston made the short film The Growler Story in 1958, depicting the action for which Lt. Cmdr. Gilmore received the Medal of Honor. In 1985, MicroProse launched Silent Service, a submarine simulator video game that allowed players to skipper famed U.S. submarines on war patrols, including Tang (SS-306), Bowfin (SS-287), Seawolf (SS-197), Spadefish (SS-411), and Growler. Two years later, Japanese company Nintendo Entertainment System released a version of the popular game for their top-selling video game systems.

Growler received eight battle stars for her service in World War II.

| Commanding Officer | Date Assumed Command |

| Lt. Cmdr. Howard W. Gilmore | 20 March 1942 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Arnold F. Schade | 7 February 1943 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Thomas B. Oakley, Jr. | 23 April 1944 |

Guy J. Nasuti

6 February 2018