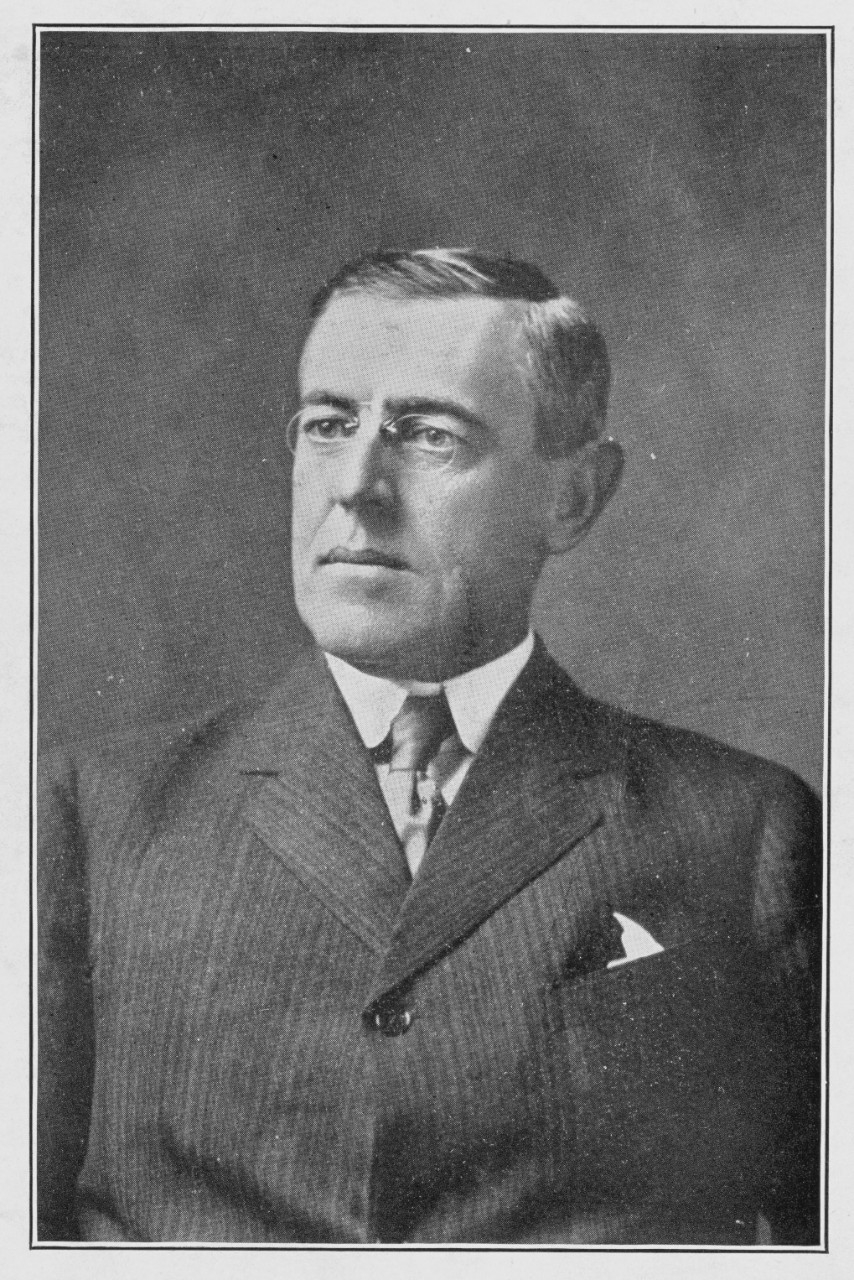

Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and Freedom of the Seas

In formulating his Fourteen Points, the conditions whereby World War I might be ended, President Woodrow Wilson also laid out the justification for U.S. entry into the war in 1917. The casus belli, he suggested, was the belligerents’ repeated disregard for a centuries-old doctrine, the principle of the freedom of the seas.

The modern concept of freedom of the seas originated in the struggle between the Dutch and Habsburg Spain in the 17th century. Defending Dutch merchants’ right to ply the lucrative East Indies trade routes, still largely under the control of the navies of Spain and Portugal, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius published his book Mare Librum in 1609. In it, he provided the legal justification for keeping the world’s waterways open to the free transit of people, raw materials, and goods. Some forty years later, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) effectively limited European states’ sovereignty to territories and coastal waters, ensuring that Grotius’s concept of freedom of the seas would become a doctrine that has lasted to the present day—but not without challenges.[1]

Hugo Grotius, marble bas-relief in the chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives in the United States Capitol, sculpture by C. Paul Jennewein (courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol).

Early in its history, the United States saw its right to the freedom of the seas directly challenged by the privateers of revolutionary France, the corsairs of the North African Barbary states, and the frigates of the Royal Navy. Presidents from John Adams to James Madison relied on the doctrine of the freedom of the seas to assert the right of U.S.-flagged ships to ply the world’s oceans unencumbered. As an extension of these assertions, the young republic fought three wars (two of them undeclared) in the period 1801–1814. As a precedent, therefore, the United States had clearly demonstrated its willingness to fight to maintain the freedom of the seas. This determination would again be put to the test in the second decade of the 20th century.

When World War I began, in the summer of 1914, it put a serious strain on the maintenance of the doctrine of the freedom of the seas. As naval blockades took shape in northern and western Europe, Washington, still neutral, rushed to assert the rights of U.S.-flagged ships in international waters. Then, as now—especially in the South China Sea—the U.S. government found itself defending the doctrine of the freedom of the seas against foreign navies seeking exclusive control of international waters.

Freedom of the Seas in the First Year of War

At the outbreak of war, the U.S. State Department formally requested that the warring nations abide by the 1909 Declaration of London, which had asserted that the rights of neutrals to engage in free trade on the seas superseded the right of belligerents to engage in naval blockade.[2] The declaration had also divided goods into three categories: absolute contraband that concerned those materials with military use, conditional contraband that could have either military or civilian uses, and a free list of items like foodstuffs and other non-military materials.[3] As such, a belligerent who had declared and established a blockade in accordance with international law could legally seize materials in the first category, while conditional contraband was subject to seizure only if proof existed that it was bound for the enemy. Materials on the free list could never be seized. The Germans and their Austro-Hungarian ally (the Central Powers) agreed to continue to abide by the Declaration, provided Britain and her allies (the Entente) did likewise.

Speaking on behalf of the Entente on 6 August 1914, the British expressed concurrence but stipulated that they reserved certain rights “essential to the conduct of their naval operations.”[4] As historian G. J. Meyer notes, Britain was asserting “that she would follow the rules to the extent that she found it to her own advantage.”[5] Great Britain, at the time of the Declaration of London, had been the world’s preeminent naval power and possessed the largest mercantile fleet. As such, the British had the greatest interest in the free flow of commerce.[6] In the years subsequent, however, those who wished to maintain Britain’s naval supremacy reconsidered this position and increasingly opposed the declaration and worked to undermine it. This resulted in the House of Lords failing to ratify the declaration.

In a further repudiation of the declaration, the British Committee of Imperial Defence established a technical subcommittee on 26 January 1911. Named for its chairman, Lord Hamilton Cuffe, Earl of Desart, the Desart Committee was to consider the question of trade with the enemy in time of war.[7] The report recommended that at the outbreak of war, Britain should prohibit “all trade with the enemy in goods, wares, and merchandise.”[8] While it was deemed probable that this policy would have a negative impact on the economy, causing protests by U.K. and colonial mercantile interests and spurring diplomatic complications with neutrals like the United States, the committee believed that Britain would suffer far less than a prospective enemy like Germany.

Blockade as a British naval strategy had repeatedly proven successful, yet the Desart Committee’s recommendations encompassed much more than just naval strategy. The committee was in fact proposing nothing short of economic warfare, the “foundation of national grand strategy, within which naval strategy had become a subset,” as historian Nicholas Lambert observes.[9] While the British never implemented this strategy to its fullest, as the consequences of doing so may have wrought destruction of the world economy, the intention itself indicates the lengths to which His Majesty’s government might go in pursuit of victory.

And so, in pursuit of victory, the British government declared a blockade in 1914 in order to exact an economic toll on Germany. In furtherance of this goal, the British also added to the list of items they deemed to be absolute contraband. The most consequential of these, even when carried in the holds of neutral ships, was foodstuffs, a “radical departure from precedent,” according to Meyer, and a “flouting of the law as understood by all seafaring nations.”[10] Robert Lansing, Counselor to the U.S. Secretary of State, wished to issue a note of protest as this was a clear violation of U.S. rights, but Wilson directed that he withdraw it in order to avert a diplomatic crisis.

Robert Lansing. (courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-30260)

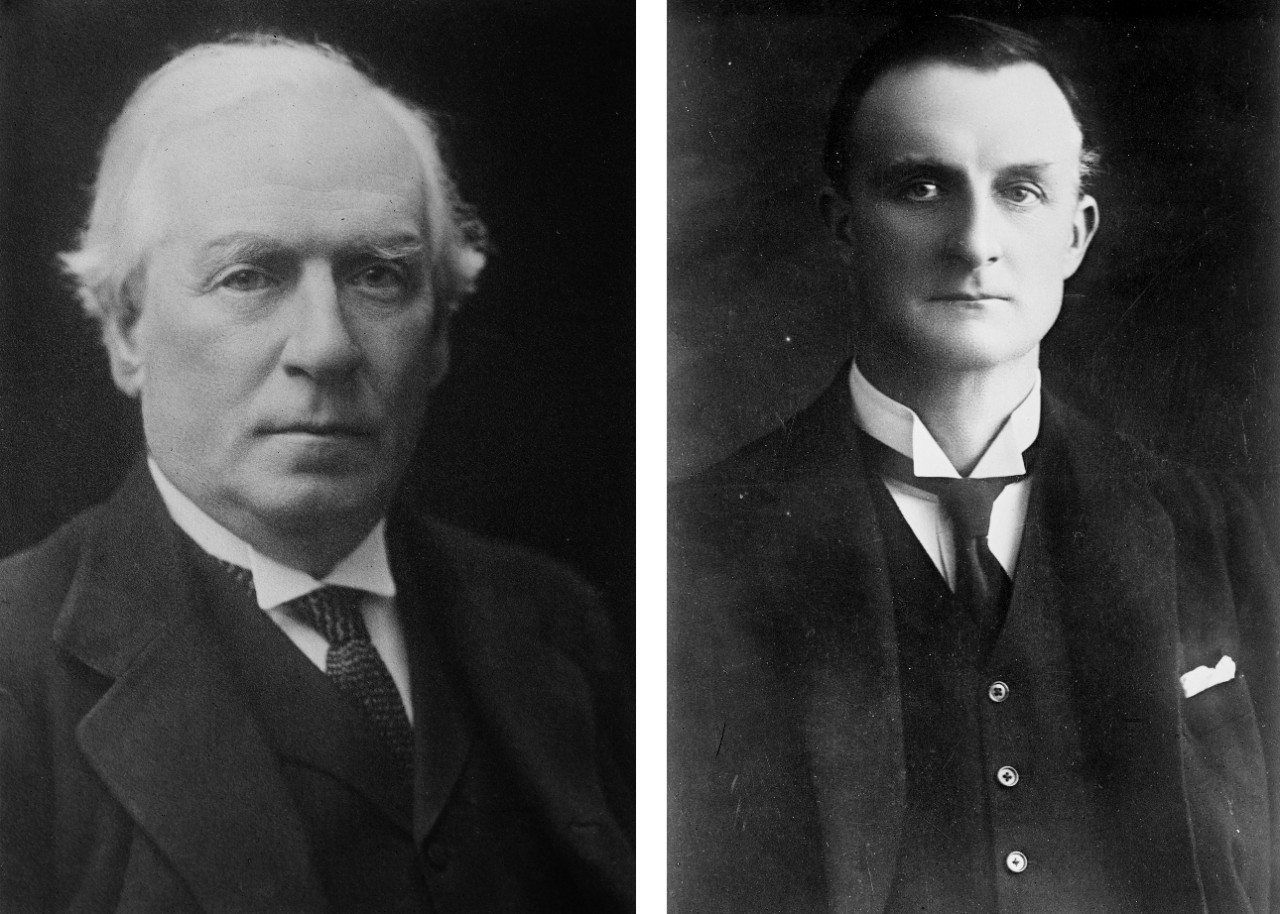

Prime Minister Herbert H. Asquith’s cabinet was mindful of the likelihood that the blockade might cause a row with neutrals, especially the United States. Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, insisted that the “United States be handled with care."[11] Representative of this sentiment was the issuance of an Admiralty Order to the fleet on 17 August 1914 directing that “great care is to be taken in the diversion of neutral ships with neutral cargoes,” as “it is of prime importance to keep the United States of America as a friendly neutral."[12] Despite these cautions, British policies increasingly antagonized the United States and its president, much as in the preceding century.

The development of new naval technologies—floating mines, longer-ranged guns, and speedy boats and submarines firing self-propelled torpedoes—made the exercise of a traditional close blockade untenable, however. While German merchant ships had largely ceased to operate after the war’s outbreak, Germany still received goods transshipped through neighboring or neutral countries. Intent on staunching this flow of material goods, the British proclaimed a “long-distance” blockade wherein they intercepted neutral shipping en route to Scandinavia and the Netherlands.[13] The British Cabinet issued an Order in Council on 20 August 1914, pronouncing that conditional contraband was subject to seizure if it was consigned to the enemy or “agent of the enemy,” or if the ultimate destination was an enemy belligerent. This policy, an application of the doctrine of “continuous voyages,” had been enacted by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars to deny the right of neutrals to trade with France, Spain, and their colonies. It had contributed to the U.S. declaration of war in 1812.[14]

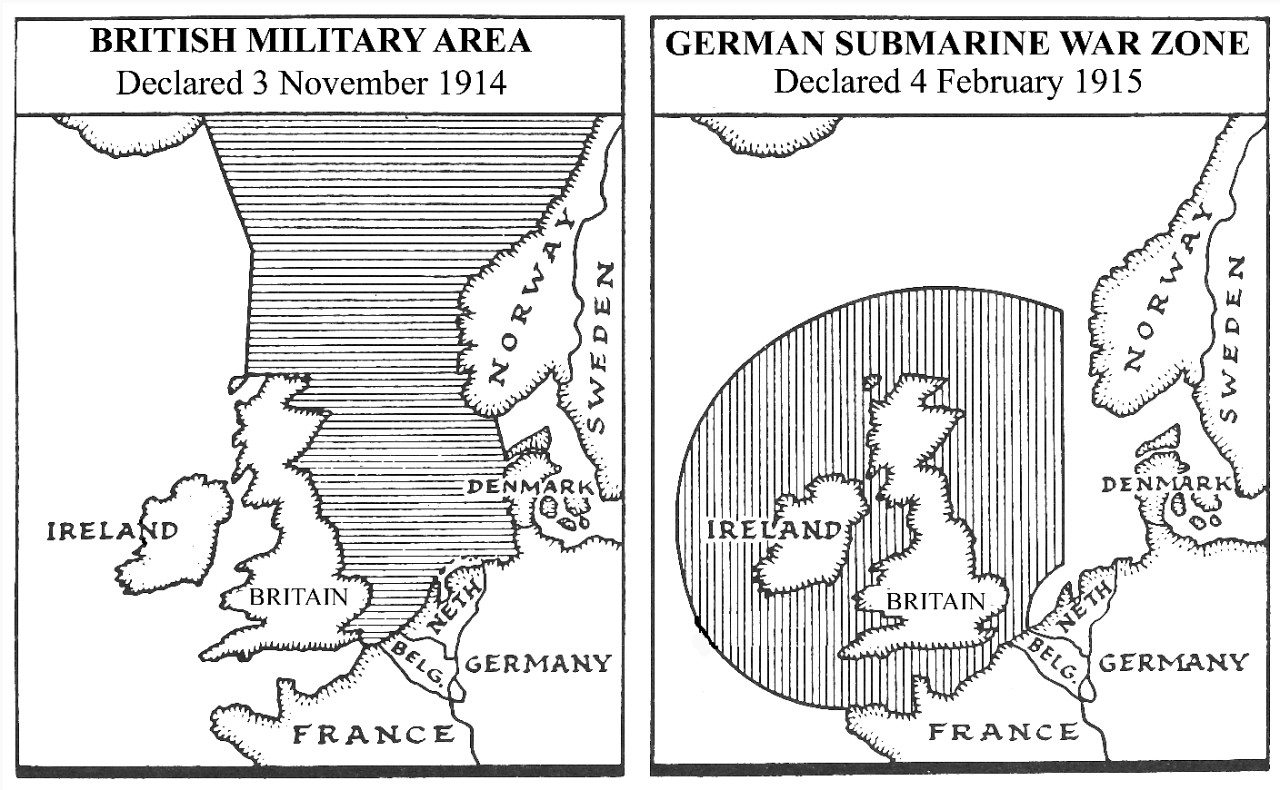

Despite this precedent, Britain’s execution of its economic strategy took primacy over the assertions of the United States and other neutrals to the freedom of the seas. In a further attempt to legitimize its blockade, Great Britain declared that it was “necessary to adopt exceptional measures appropriate to the novel conditions under which the war is being waged.” The British then designated the entire North Sea a “British Military Area” on 3 November 1914. In an unprecedented move, the British proclaimed that these international waters were now susceptible to mining.[15]

While the British had determined to employ the Royal Navy in an economic warfare campaign from the war’s onset, the Germans never had any such intentions for the Imperial German Navy. Yet, as historian Lawrence Sondhaus notes, “Once it became clear that Britain, in its quest to close Germany’s ports, had no intention of honoring the provisions of the prewar Declaration of London that allowed food and other non-military cargoes to pass through a blockade, the Germans began to consider ways to… inflict a similar hardship on the British."[16] The means by which they would accomplish this was the Unterseeboot or U-boat (submarine).

German U-Boats early in the war. U-20 is second from left. The text in the lower left translates to “Our U-boats in port.” (Library of Congress, LC-B2-3292-13)

When the war broke out, the Imperial German Navy only had 36 operational U-boats, which saw them lag behind all the Entente navies. These U-boats were small, slow, and of limited range. Much as in the Royal Navy, German naval officers envisioned submarines as defensive in nature and a means to counter close blockade.[17] There was little thought given to deploying U-boats in an offensive capacity.[18] Yet just a few weeks into the war, on 22 September 1914, U-9, under Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen, torpedoed and sank three obsolescent British cruisers, Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue, in a matter of hours. Korvettenkapitän (Corvette Captain) Hermann Bauer, commander of the German U-boat flotilla in the North Sea, proposed on 8 October to commence a Handelskrieg (commerce-raiding campaign) with U-boats along the British coast. This was ostensibly a retaliatory measure for the British mining the approaches to the English Channel east of the Dover–Calais line, which Bauer considered a violation of international law.[19]

The following month, on 18 October, U-27, under Kapitänleutnant Bernd Wegener engaged and sank the British submarine E-3 at the mouth of the Ems River. Then two days later, on 20 October, U-17, Kapitänleutnant Johannes Feldkirchener commanding, in accordance with cruiser rules or, more appropriately, the “prize rules of war,” stopped, boarded, searched, and then scuttled the Norway-bound British steamer Glitra. This was the first merchant ship sunk by a U-boat. Then on 26 October, in a move that set an ominous precedent, Kapitänleutnant Rudolf Schneider’s U-24 torpedoed the 4,590-ton Amiral Ganteaume, believing her to be an auxiliary cruiser. The vessel, however, was a French passenger ship en route from Calais to Le Havre, France, with 2,500 Belgian refugees embarked.[20]

Despite these sinkings, there was still no German intent to conduct a Handelskrieg; warships remained the U-boats’ primary targets. Five days after the British declaration regarding the North Sea, however, Vizeadmiral Hugo von Pohl, Chief of the Admiralstab (German Imperial Admiralty Staff), circulated a draft declaration establishing a submarine blockade of Great Britain and Ireland.[21] Korvettenkapitän Bauer then submitted a further memorandum at the end of December claiming that Germany would have sufficient U-boats in service to initiate a campaign against commerce by the end of January 1915.[22]

The Entente had largely sunk, captured, or forced the internment of Germany’s surface raiders by the end of 1914. With the sea lanes secured, the British and French could transport troops and supplies from their vast colonial empires unencumbered to European battlefields while simultaneously severing Germany from her overseas possessions in Africa, China, and the Pacific.

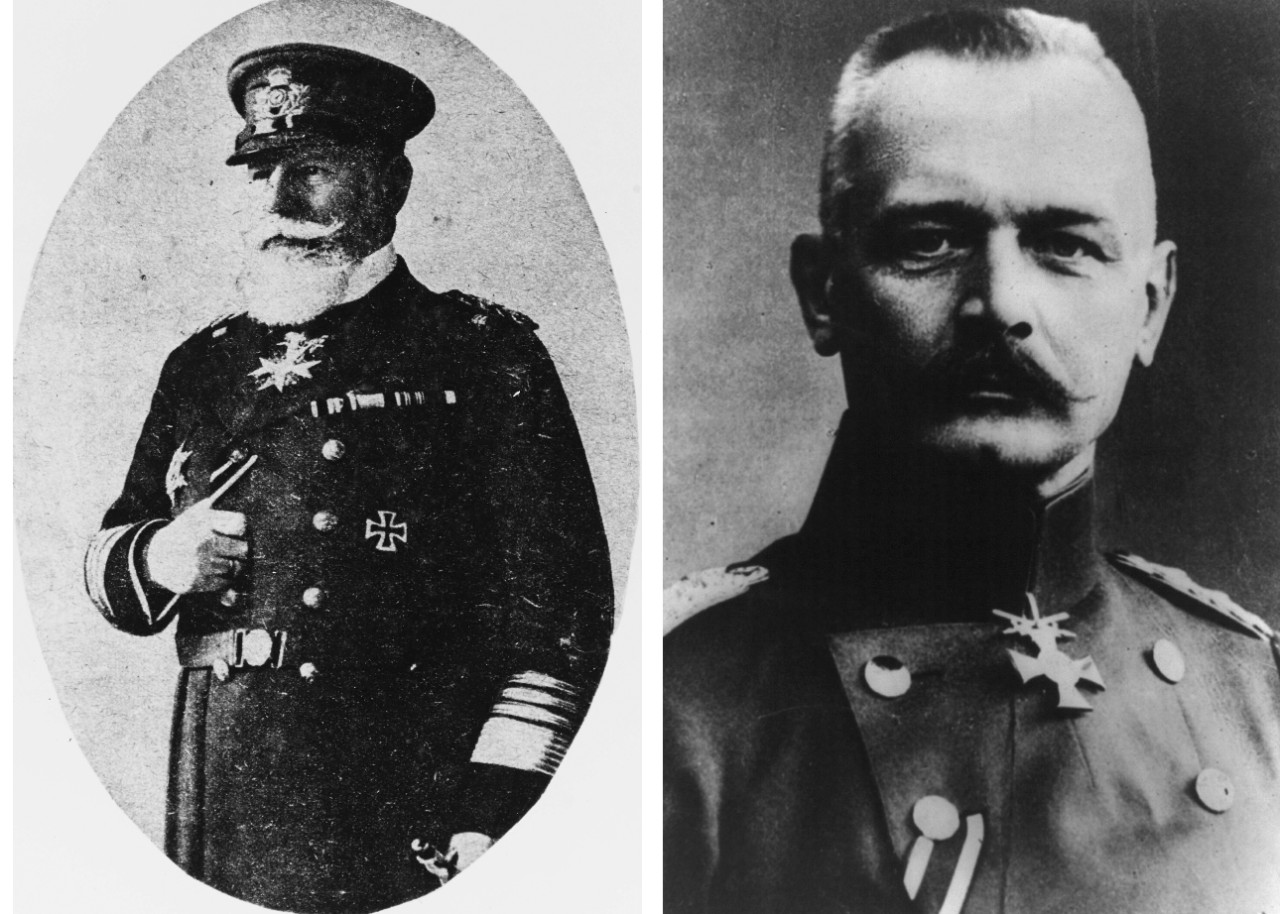

Pohl’s nascent notion of a counter-blockade of the British Isles eventually took root. The prospects of such a campaign intrigued Kaiser Wilhelm II, especially, but Groβadmiral Alfred von Tirpitz, Secretary of State of the Reichsmarineamt (German Imperial Naval Office) was initially cool to the scheme. Even more so was Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, who feared the potential diplomatic consequences, particularly as they concerned the United States.

Frustrated by the impotence of their surface fleet, however, and facing the prospect of the constriction of their economy, the Germans believed that they had to counter Britain’s blockade. As a result, two days after he succeeded Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl as commander of the High Seas Fleet, Pohl announced on 4 February 1915 that the “waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, are hereby proclaimed a war region. On and after February 18 every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without it always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening.”[23] Germany had launched the first unrestricted submarine warfare (USW) campaign.

Kaiser Wilhelm II. : Photograph presented by the kaiser to USS Louisiana (BB-19) at Kiel in June 1911. Second division of the U.S. Atlantic fleet was there during yachting week. Since it was the emperor's ambition to make the Kiel yachting week a worthy rival of the English cowes week, he was present on board the imperial yacht Hohoenzollern and nearly all the German high seas fleet was also present. Twice he visited the Louisiana, once to inspect the ship, and once as a luncheon guest of Rear Admiral Charles J. Badger, who was commander of the second division, and Louisiana was flagship with Captain Winterhalter as commander. (NH 1021)

The world reacted with horror at the announcement of the unprecedented strategy. President Wilson issued a “Strict Accountability” warning to Germany on 10 February 1915. He urged “the Imperial German Government to consider, before action is taken, the critical situation in respect of the relation between this country and Germany which might arise were the German naval force, in carrying out the policy foreshadowed in the Admiralty’s proclamation, to destroy any merchant vessel of the United States or cause the death of American citizens.” Citing international law regarding the prize rules,[24] Wilson reminded the Germans “that the sole right of a belligerent in dealing with neutral vessels on the high seas is limited to visit and search, unless a blockade is proclaimed and effectively maintained, which this Government does not understand to be proposed in this case. To declare or exercise a right to attack and destroy any vessel entering a prescribed area of the high seas without first certainly determining its belligerent nationality and the contraband character of its cargo would be an act so unprecedented in naval warfare that this government is reluctant to believe that the Imperial Government of Germany in this case contemplates it as possible.”[25] More to the point, as indicated by the reaction to interviews with Tirpitz before the announcement, the American public would never accept the German argument that their USW campaign against Britain was no less moral or legal than Britain’s blockade of Germany.[26]

The war zones declared by Britain and Germany.

In response, Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered all U-boat commanders to spare neutral ships in the designated war zone on 15 February 1915. Bethmann Hollweg followed two days later with a note to Wilson implying that the Germans would suspend their campaign if the United States could persuade the British to adhere to the Declaration of London.[27] The British refused, and the German campaign commenced on 18 February.

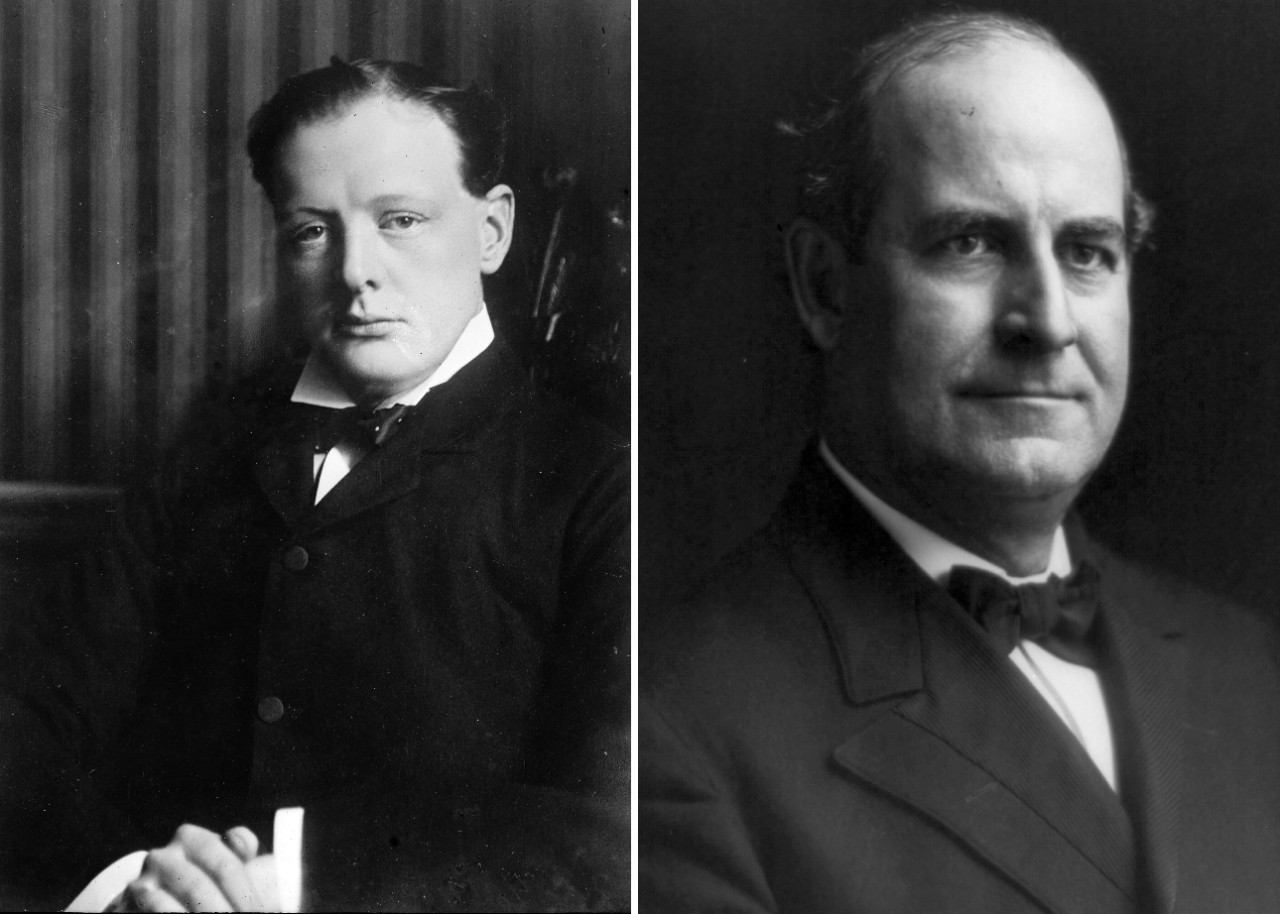

Winston S. Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, believing the USW campaign to be an illegitimate form of warfare, directed that captured U-boat personnel should be charged as war criminals rather than being afforded the protections and rights of prisoners of war.[28] Meanwhile, the Wilson administration, particularly Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, questioned the legitimacy of both nations’ actions.[29]

left: Winston S. Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. (Library of Congress, LC-B2-1016-13)

right: Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-95709)

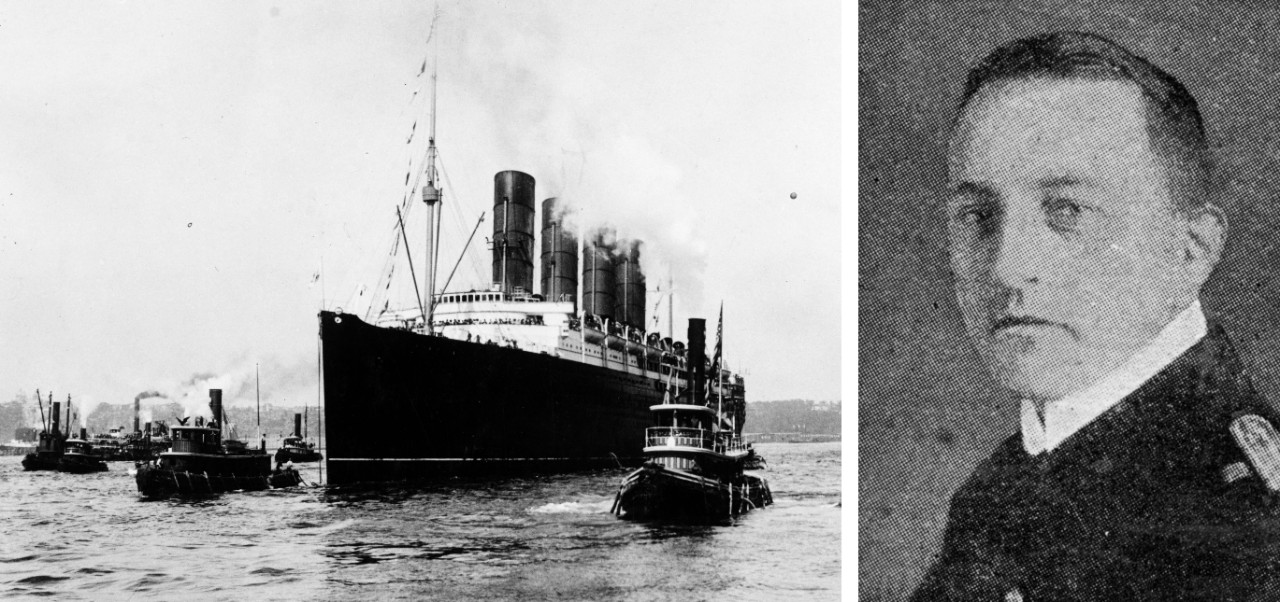

In the campaign’s first few months, the Germans began to have increased success in sinking Allied shipping. In fact, six U-boats sank 31 ships between 1 May and 6 May 1915. British and French countermeasures were obviously ineffective.[30] However, the U-boats’ successes concealed an underlying failure. The tons of cargo sunk did not quite outweigh the diplomatic problems for Germany that its policy of USW was now creating, especially vis-à-vis the United States.[31] In particular, with a single event in May 1915, Germany’s diplomatic problems turned into a diplomatic crisis that ultimately transformed the Germans’ USW campaign. On the afternoon of 7 May, Kapitänleutnant Walter Schwieger’s U-20 torpedoed RMS Lusitania, the 30,396-ton Cunard passenger liner, 11 miles south of the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland. Bound from New York to Liverpool, the ship sank in 18 minutes with the loss of 1,198 souls, 128 of them U.S. citizens.

(Left) Lusitania departs New York on her final voyage, 1 May 1915 (National Archives, 111-SC-95818)

(Right) Kapitänleutnant Walter Schwieger (NH 120872)

After the Lusitania Disaster

Lusitania’s grievous human losses changed the calculus by which the United States assessed German actions, both publicly and politically. Wilson drafted an official protest to the German government, issued by the State Department on 13 May 1915, wherein he cited three earlier attacks on U.S.-flagged ships.[32] Continuing, Wilson emphasized the broader principles of the “freedom of the seas” before questioning at length Germany’s USW campaign. He noted that even though “the government of the United States has been apprised that the Imperial German government considered themselves to be obliged by the extraordinary circumstances of the present war and the measures adopted by their adversaries in seeking to cut Germany off from all commerce,” Germany’s “methods of retaliation,” particularly the warning “that neutral ships keep away,” had gone “much beyond the ordinary methods of warfare at sea.”[33]

Wilson then asserted “the indisputable rights” of “American citizens” to go “wherever their legitimate business calls them upon the high seas.” Invoking the long history of the doctrine of the freedom of the seas, Wilson further insisted that Americans should be able to approach international waters with the “confidence that their lives will not be endangered by acts done in clear violation of universally acknowledged international obligations.”

Next, Wilson took up the issue of U-boats as commerce raiders from the perspective of international law. “It is practically impossible,” he reasoned, “for the officers of a submarine to visit a merchantman at sea and examine her papers and cargo… and for them to make a prize of her; and, if they cannot put a prize crew on board of her, they cannot sink her without leaving her crew and all on board of her to the mercy of the sea.” Returning to his theme of freedom of the seas as an element of natural law—much as Grotius had done three centuries prior—Wilson called the use of U-boats against neutrals on the high seas a “violation of the many sacred principles of justice and humanity.”[34]

The U.S. public generally approved of Wilson’s argument, which asserted Americans’ natural rights as neutrals on the high seas but stopped short of threatening war, still an unpopular option.

Here Lie “the Facts”, a political cartoon by William A. Rogers published on the front page of the New York Herald, 29 May 1915. Uncle Sam faces Kaiser Wilhelm II, while standing behind the flag-covered bodies of the U.S. children killed in the Lusitania sinking. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-105673)

It took the Germans two weeks to respond to Wilson’s official protest. Gottlieb von Jagow, State Secretary of the German Foreign Office, dispatched his government’s reply on 28 May, asserting that the attack on the neutral ships were mistakes representing “a question of isolated and exceptional cases…. This Government has expressed its regret at the unfortunate occurrence and promised indemnification where the facts justified it.”[35]

Jagow then provided a justification for the sinking of Lusitania. It was a military target, “one of the largest and fastest English commerce steamers, constructed with Government funds as auxiliary cruisers, and is expressly included in the navy list published by the British Admiralty.”[36]

Germany’s official response notwithstanding, Wilson’s protest had a profound impact on both Wilhelm II and Bethmann Hollweg. The chancellor went so far as to inform the Admiralstab that he “refused to be responsible for the campaign in its existing form.”[37] He persuaded Wilhelm II to follow Jagow’s apology for the attacks on the U.S.-flagged ships with a renewal of earlier orders against targeting neutrals on 6 June. The Kaiser also banned attacks on large passenger liners, including those of the Entente nations.[38]

Gottlieb von Jagow. (Library of Congress, LC-B2- 3764-10)

While both the British and the Germans had infringed on the rights of the United States and other neutrals to the freedom of the seas, there was a clear delineation in Wilson’s mind as to whose policies were more offensive. Writing to Lansing on 2 June 1915, Wilson declared, “England’s violation of neutral rights is different from Germany’s violation of the rights of humanity.”[39] Believing that Wilson’s policies toward the belligerents were ineffective and likely to lead to war with Germany, Bryan resigned as Secretary of State on 8 June 1915. Lansing subsequently replaced him and increasingly advocated for intervening on the side of Britain and the Entente.

The following day, 9 June, Wilson issued a second note as a response to Jagow’s communications. While the United States was gratified by the “frank willingness of the Imperial German Government to acknowledge and meet its liability” for the attacks on U.S.-flagged ships, Wilson was still outraged by German USW practices. “Whatever be the other facts regarding the Lusitania,” he continued, “the principal fact is that a great steamer, primarily and chiefly a conveyance for passengers, and carrying more than a thousand souls who had no part or lot in the conduct of the war, was torpedoed and sunk without so much as a challenge or a warning, and that men, women, and children were sent to their death in circumstances unparalleled in modern warfare.” The idealistic Wilson then proclaimed, the “Government of the United States is contending for something much greater than mere rights of property or privileges of commerce. It is contending for nothing less high and sacred than the rights of humanity, which every Government honors itself in respecting and which no Government is justified in resigning on behalf of those under its care and authority.” He then closed by stating that the U.S. expected the Germans to “adopt the measures necessary to put these principles into practice in respect of the safeguarding of American lives and ships” and asked “for assurances that this will be done.”[40]

The Germans replied on 8 July 1915 with a simple reiteration of their 28 May communication. This prompted Wilson to issue a third protest on 21 July. The sternest yet, the note declared that the “rights of neutrals in time of war are based upon principle, not upon expediency, and the principles are immutable. It is the duty and obligation of belligerents to find a way to adapt the new circumstances to them.” The United States “will continue to contend for that freedom, from whatever quarter violated, without compromise and at any cost.” Then issuing a further caution, Wilson warned that any “repetition by the commanders of German naval vessels of acts in contravention of those rights must be regarded by the Government of the United States, when they affect American citizens, as deliberately unfriendly.”[41] This third note prompted a brief respite of tensions between Germany and the U.S.

Even with the diplomatic complications arising from Lusitania’s sinking, the Germans continued their USW campaign, achieving marked levels of success. Primarily using deck guns, rather than torpedoes, U-boats sank more than 100,000 tons of merchant shipping every month from May to August 1915.[42] Given these practices, however, the reemergence of tensions was inevitable.

Kapitänleutnant Rudolf Schneider’s U-24 torpedoed and sank the 15,801-ton, British-flagged passenger liner Arabic off the southern coast of Ireland on 19 August 1915. Among the 44 dead were two Americans.[43] In response, President Wilson’s closest advisors urged the severing of diplomatic relations with Germany. Wilson declined, wanting to give the Germans the opportunity to disavow the attack. In conveying that message, however, Lansing intimated that the United States was prepared to declare war if the Germans did not suspend their USW campaign.[44]

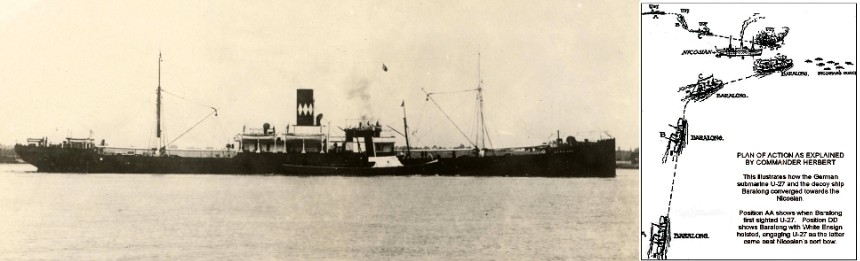

An episode at sea that same day illustrates the double standard at work when it came to violations of international law at sea—a double standard that indicated Wilson and Lansing’s preference for the British, even in face of serious infractions committed by the Royal Navy. The episode occurred when Kapitänleutnant Bernd Wegener’s U-27 encountered Nicosian, a British-flagged freighter en route from New Orleans to Liverpool with a load of mules. Wegener had his crew fire a warning shot from two miles distant. Hearing it, most of the British freighter’s crew abandoned ship. Then, just as U-27 was approaching its quarry, a tramp steamer flying a U.S. flag closed in.

The flag was a ploy. The tramp steamer was actually HMS Baralong, a Q-ship under Commander Godfrey Herbert, RN. At 100 yards from U-27, HMS Baralong lowered the U.S. flag and let fly the Royal Navy’s white ensign. The ship’s crew then opened fire on U-27 and sank it.[45] While the German embassy in Washington protested the use of the U.S. flag by the British, the Admiralty responded that Baralong was a defensively armed steamer and the ship’s actions were a legitimate ruse of war. Furthermore, the crew had complied with international law, according to the Admiralty, by striking the ship’s true colors in advance of attacking the German submarine.

Whereas Lansing had threatened the Germans with a possible declaration of war after the Arabic sinking, he issued no formal protest to the British after the deceitful use of the Stars and Stripes.[46] In subsequent correspondence, Wilson called the incident “horrible,” and Lansing called it “shocking,” yet their inaction only confirmed the double standard they had already adopted in their reactions to the respective transgressions of international law by the British and the Germans.[47]

(Left) The Q-ship HMS Baralong (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Baralong.jpg)

(Right) Depiction of encounter between HMS Baralong and U-27 (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/eb/HMS_Baralong_vs_SM_U-27.jpg)

With these contradictory responses to the events of 19 August 1915, the United States, not surprisingly, found itself closer to war with Germany. Whereas Jagow had boasted on 15 August that Germany “would not allow its submarine policy to be influenced by America,” Bethmann Hollweg expressed to Tirpitz on 26 August his intention to communicate to Wilson that “submarine commanders had definite orders to not torpedo passenger steamers without warning and without opportunity being given for the rescue of passengers and crew.”[48] Tirpitz and Admiral Gustav Bachmann, Chief of the Admiralstab, tendered resignations in protest.

In response, the Kaiser relegated Tirpitz to an advisory role and replaced Bachmann with Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff. In short order, the new head of the Admiralstab joined with Bethmann Hollweg and General Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, Supreme Army Command) “in favor of a more definitive, unambiguous end to unrestricted submarine warfare that would require U-boats to conform to traditional cruiser rules in their approach to unarmed ships.”[49] The Kaiser concurred and ordered the U-boat force to employ the cruiser rules, effective 18 September 1915.

Even though the campaign’s last two months, August and September 1915, saw the greatest totals of sunken tonnage, the USW campaign was suspended. In seven months, Germany’s 49 U-boats had sunk approximately 750,000 tons of shipping. However impressive, these losses had a negligible impact on Britain’s war effort. After all, the British had entered the war with more than 21 million tons of merchant shipping. Moreover, the British were able to replace all losses and more with the construction of new vessels and the capture of German and Austrian merchant vessels. The amount of tonnage available to the Entente rose, not fell, during this period. In addition, neutrals seeking profit were undeterred in trading with the British Isles.[50]

The Germans were simply unable to deploy sufficient numbers of U-boats with the requisite capabilities, especially concerning the amounts of ordnance and time on station during war patrols, to blockade the British Isles and effectively sever the lifeline of men and matériel. As historian Jan Breemer explains, “the failure of the first offensive had far less to do with the efficiency of British defensive measures than the U-boats’ self-imposed restrictions.”[51] Much as Bachmann had predicted, a USW campaign undertaken with inadequate U-boats and inconsistent political support would not secure German victory but would be “enough to create incidents and quarrels with the Americans.”[52] The repercussions of those quarrels would prove consequential in 1917.

The United States Prepares for War

Amid the diplomatic wrangling with both Britain and Germany, Wilson felt compelled to initiate policies for increased U.S. military preparedness.[53] On the same day he issued his third Lusitania note, 21 July 1915, Wilson charged Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison to “draw plans for the full development of the fighting arms of the nation.”[54] Daniels was to consult with the Navy’s General Board and other experts to determine what the Navy must do “to stand upon an equality” with the best in the world.[55] The General Board agreed that “the Navy of the United States should ultimately be equal to the most powerful maintained by any other nation of the world.”[56] The recommendation was for the U.S. to build a navy “second to none.”

Daniels charged the General Board on 7 October with preparing an unprecedented five-year shipbuilding program (FY1917–21) allocating $100 million per annum for the construction of new ships. The Board responded with a proposal on 12 October that shaped Daniels’s report to the President on 1 December.[57] Without articulating a specific strategy, Wilson fully embraced the planned annual naval estimates to be submitted to the 64th Congress.[58]

(Left) Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels. (Library of Congress, LC-H25-990048)

(Right) Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-100793)

Wilson’s intention with the naval program was to ensure the United States’ strategic freedom in the years ahead. Regardless of who might win the war, challengers to U.S. interests were likely to emerge. How else was the United States to ensure not just the freedom of the seas, but also her rights to freedom of action in world affairs? Given the strained relations with Britain over the rights of neutrals, the President revealed his intentions to his close advisor, Edward “Colonel” House: “Let us build a Navy bigger than hers and do what we please.” In short, as historian George Baer notes, “This was sea power in the interest of American unilateralism.”[59]

The General Board elaborated further on why the United States Navy must be “equal to the most powerful” by 1925:

Defense from invasion is not the only function of a Navy. It must protect our seaborne

commerce and drive that of the enemy from the sea. The best way to accomplish all these objects is to find and defeat the hostile fleet or any of its detachments at a distance from our coast sufficiently great to prevent interruption of our normal course of national life. The current war has shown that a navy of the size recommended by this board in previous years can no longer be considered as adequate to the defensive needs of the United States. Our present Navy is not sufficient to give due weight to the diplomatic remonstrances of the United States in peace or to enforce its policies in war.[60]

Wilson then took these considerations to Congress. In his State of the Union address on 7 December 1915, Wilson revealed to a congressional joint session his rationale for national preparedness. The United State required a larger fleet along with corresponding manpower increases for the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps in order to maintain its neutrality and continue to enforce the Monroe Doctrine.[61] Considering the Navy to be the first line of defense, he proposed that Daniels’s five-year warship construction program become law. Wilson also reiterated his call for the government to subsidize a greatly expanded merchant marine.[62] Finally, he laid out his plan to pay for these preparedness measures with various internal taxes that he considered reasonable and which would spread the burden without incurring great national debt.

The following month, in early 1916, Wilson embarked on a speaking tour to garner public support for the preparedness initiatives. In his last two speeches in Kansas City and St. Louis, Wilson spoke with greater stridency, postulating that a second-rate navy was no longer good enough. He called for a fleet that was “practically impregnable”—“the greatest navy in the world.”[63]

While there were still some members of Congress, mainly in the House, opposed to a naval building program, popular sentiment largely favored the endeavor. Introduced as H.R. 15947 on 27 May 1916, the Naval Appropriations Act of 1916 became law on 29 August. It provided for the construction of 156 ships of all classes to be laid down before 1 July 1919. The law also boosted work force in both the Navy and the Marine Corps and established a Naval Reserve.[64]

Ironically, the tactically indecisive Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916 provided greater impetus for the passage of the bill.[65] As George Baer noted, “Congress agreed to the construction, without interruption, of 156 ships. The preparedness campaign was won. The Navy for the first time had a continuous, comprehensive schedule for the construction of warships. One hundred and fifty-six vessels of all classes were to be begun by July 1919, with construction to be finished by 1922 or 1923.”[66] With the passage of this legislation, the U.S. Navy had clearly entered a new age.

German Actions and the U.S. Entry into the War, 1916–17

While the United States determined the future course of its Navy, the Imperial German Navy continued its restricted submarine warfare campaign during the latter months of 1915 and through 1916. Germany also continued, at Tirpitz’s insistence, a U-boat construction program which included improving capabilities in the event of the resumption of USW.

All the while, German military and civilian leaders engaged in internal policy struggles regarding the propriety of undersea warfare against neutral shipping, as well as in reaction to Wilson’s protests and ultimatums.[67] For Bethmann Hollweg and most of the other civilian ministers, the results showed that unrestricted submarine warfare was unnecessary, while for Tirpitz and his allies, the demonstration of what could be accomplished with restricted submarine warfare led to speculation about just how devastating a properly prepared and supported unrestricted campaign could be.[68]

Even though the Germans had issued assurances regarding the targeting of passenger vessels, UB-29, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Herbert Pustkuchen, mistakenly torpedoed the British ferry Sussex on 24 March 1916, believing it to be a minelayer. The vessel sustained heavy damage. Fifty died and hundreds, including three Americans, sustained injuries. The attack infuriated Wilson, who “considered the sacred and indisputable rules of international law and the universally recognized dictates of humanity” to have been violated. If Germany did not immediately cease these attacks, the United States would be forced to break off diplomatic relations.[69] In response, Bethmann Hollweg issued the Sussex Pledge on 4 May 1916, wherein Germany promised to no longer attack any passenger ships, thus expanding on the previous Arabic Pledge, which had stated that merchant vessels would only be sunk if war matériel were onboard, but only after all passengers, including the crew, had left the ship.

The expanded pledge appeased the United States and eventually aided the German war effort. Subsequently, Vizeadmiral Reinhard Scheer, Pohl’s successor as Commander in Chief of the High Seas Fleet, decided to employ U-boats in support of the fleet’s operations, arguing that traditional cruiser warfare restrictions made commerce raiding too risky for U-boats. With this change, the focus of the submarine campaign shifted to the Mediterranean Sea.[70] German U-boats sank large amounts of military shipping in the following six months and avoided a showdown with the United States.[71] Subsequent changes in German policy, however, made that showdown inevitable.

Vizeadmiral Reinhard Scheer. (Library of Congress, LC-B2- 4121-14)

The year 1916 failed to produce a German victory, the effort at Verdun having failed to “bleed the French white” and the High Seas Fleet having failed to tilt the strategic situation in the North Sea. The British offensive on the Somme, moreover, had placed the Germans on the defensive on the Western Front, while the Russians’ Brusilov Offensive against Germany’s principal ally, Austria-Hungary, shook the alliance and forced the diversion of sizeable contingents of German troops southward to stabilize the Eastern Front. Even though the German army did enjoy a signal success with the invasion of Romania under Falkenhayn’s replacement as OHL chief, Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg and his counterpart Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff, the war still seemed hopelessly deadlocked.

Left to right, Hindenburg, Wilhelm II, and Ludendorff. (National Archives, 165-GB-1000)

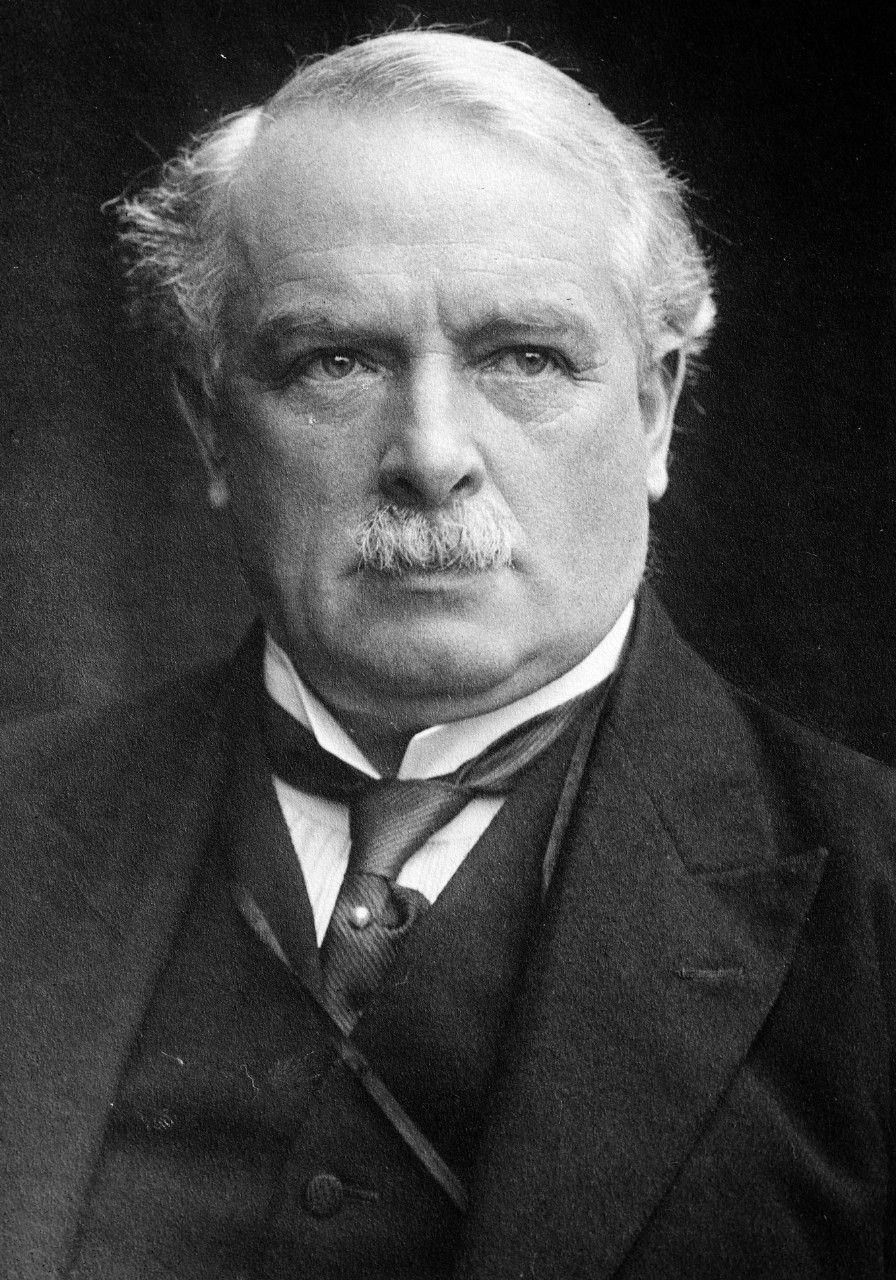

Meanwhile, the British continued to turn up the pressure with their economic warfare strategy. They established the Ministry of Blockade in February 1916 before abrogating the Declaration of London and asserting the blockade’s legitimacy under international law. Then on 6 December, David Lloyd George, already looking to further tighten the screws on the German economy in his capacity as the British Secretary of State for War, became prime minister. As 1916 turned to 1917, the British blockade produced results: the “Turnip Winter,” as Germans called it, a period of deprivation and even starvation in some parts of the empire.[72]

Meanwhile, Scheer’s fleet remained bottled up in port, having failed to break the British at Jutland. As a result, he ordered the U-boats under his command to return to commerce raiding under cruiser rules late in 1916 and suggested to Wilhelm II the possibility of the resumption of USW.[73] The tightening of the British blockade resulted in a call from the German public for renewing USW as a means of retaliation in order to “punish England,” according to the popular rallying cry.[74] Given the strategic situation, views in Berlin regarding the efficacy of USW were changing.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George. (Library of Congress, LC-B2-5604-3)

With the capture of Bucharest, the Romanian capital, on 6 December 1916, Hindenburg raised the issue of resuming USW with Wilhelm II two days later. Bethmann Hollweg, however, initially parried this proposal as he had already received the Kaiser’s consent for the extension of peace overtures to the Entente through the United States.

Holtzendorff joined with Hindenburg and Ludendorff at a conference held at Pless on 8 January 1917. Arguing for the campaign’s renewal, the three men urged the Kaiser to sack Bethmann Hollweg if he refused to support it. Faced with this overwhelming pressure from OHL and the Admiralstab, the chancellor relented in his opposition, and Wilhelm II ordered the resumption of USW, effective 1 February 1917.[75]

The drive for the resumption of USW stemmed from a communication from Holtzendorff to Hindenburg. Dated 22 December 1916, the memorandum had calculated that Britain would be required to sue for peace if Germany’s U-boats could manage to sink a monthly average of 600,000 tons of shipping over five months. The Admiralstab’s chief justified the risk of war with the United States, “so long as the U-boat campaign is begun early enough to ensure peace before the next harvest, that is, before August l,” a target date that allowed for a sixth month for the U-boat force to do its work. Holtzendorff determined that “an unrestricted U-boat campaign, begun soon, is the right means to bring the war to a victorious end for us. Moreover, it is the only means to that end.”[76] By Ludendorff’s recollection, the calculation was “to reduce enemy tonnage [so] that the quick transport of the new American armies was out of the question.” After all, the United States would not be able to intervene decisively if “a certain proportion of the transports had been sunk. The navy counted upon being able to do this.”[77]

Holtzendorff’s memorandum, moreover, shaped the campaign’s implementation, as it advised Hindenburg that “the declaration and commencement of the unrestricted U-boat war should be simultaneous so that there is no time for negotiations.”[78]

With the resumption and intensification of USW, Germany’s political, military, and naval leaders achieved the unity of purpose that had eluded them earlier in the war. Even those concerned with provoking U.S. intervention now saw no alternative given the strategic circumstances. Drastic times called for drastic measures.

The Imperial German Navy was much better prepared in February 1917 than it had been two years prior. The Germans had learned valuable lessons during the first USW campaign. Veteran U-boat officers would deploy their tactical experience, while those in charge of submarine design recognized that larger, more heavily armed U-boats with a greater range would not only be more lethal, but could also be more habitable for the men on board, thus increasing the amount of time that a boat could be kept at sea on patrol.[79]

Even before the resumption of USW, while having to comply with the restrictions of cruiser warfare, U-boats inflicted a heavy toll on Allied shipping, sinking roughly twice as much tonnage in the five months to January 1917 as they had in the seven months of USW in 1915. This was due in large part to the deployment of more U-boats, made possible by Tirpitz’s insistence on continued procurement and construction and Hindenburg’s reorganization of the labor force, which provided shipyards with a reliable supply of workers. The result was 133 deployable U-boats by the end of 1916—U-boats with better range, wireless communications, sustainability, and lethality.[80]

Bethmann Hollweg notified the Reichstag of the resumption of USW on 31 January 1917: “In now deciding to employ the best and sharpest weapon, we are guided, by a sober consideration of all the circumstances that come into question,” he assured the delegates. Nevertheless, “the most important fact of all” was “that the number of our submarines has very considerably increased as compared with last spring, and thereby a firm basis has been created for success.”[81] Germany’s leaders had calculated the hazards and determined to risk the war’s outcome on a fateful roll of the dice.

Within hours of Bethmann Hollweg’s address to the Reichstag, Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, German Ambassador to the United States, conveyed a message to Secretary Lansing giving formal notice of the resumption of USW. The notice was framed as a response to Wilson’s “Peace without Victory” speech, given to the Senate on 22 January.[82]

Bernstorff’s message condemned Britain for “using her naval power for a criminal attempt to force Germany into submission by starvation.” It then informed the United States that as of 1 February 1917, “sea traffic will be stopped with every available weapon and without further notice in the…blockade zones around Great Britain, France, Italy, and in the Eastern Mediterranean.”[83]

Wilson was outraged. The following day, 1 February 1917, he told House that Germany was “a madman that should be curbed.”[84]

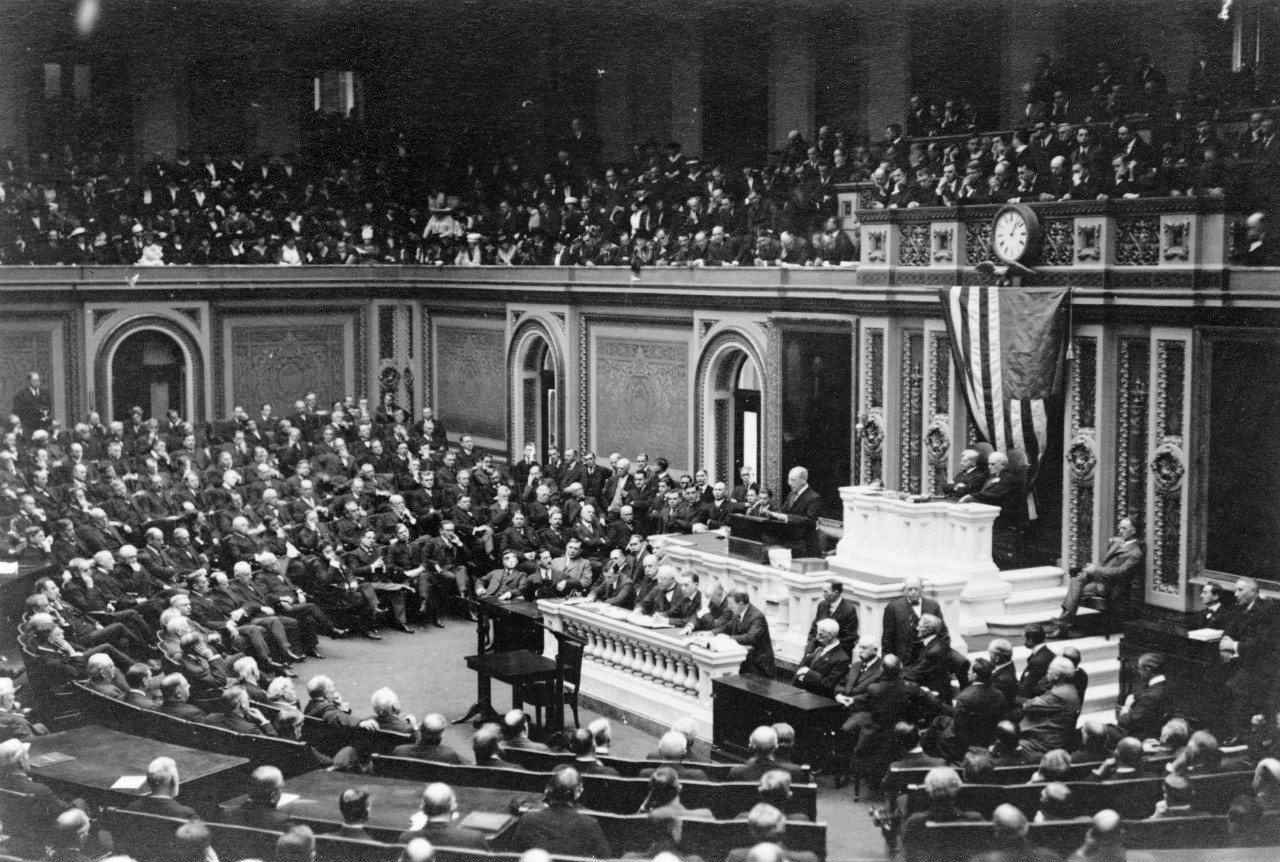

Having convened his cabinet to discuss the situation, Wilson addressed a joint session on 3 February 1917: “I have therefore directed the Secretary of State to announce to his Excellency the German Ambassador that all diplomatic relations between the United States and the German Empire are severed.”[85]

Concomitant with the severing of relations, the U.S. government seized the German ships interned in U.S. ports earlier in the war.[86] Among these were the passenger liners Kronprinz Wilhelm and Prinz Eitel Friedrich.[87]

That same day, 3 February, U-53 under Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, encountered the U.S.-flagged Housatonic en route to London with a cargo of grain. After firing two warning shots in accordance with cruiser rules, the U-boat’s crew boarded the steamer. As the ship was loaded with Britain-bound contraband, Rose ordered the steamer scuttled. He allowed the crew to take to the lifeboats in advance of breaking the ship’s seacocks and firing a single torpedo. U-53 then towed the lifeboats landward until a British patrol craft appeared on the horizon.[88]

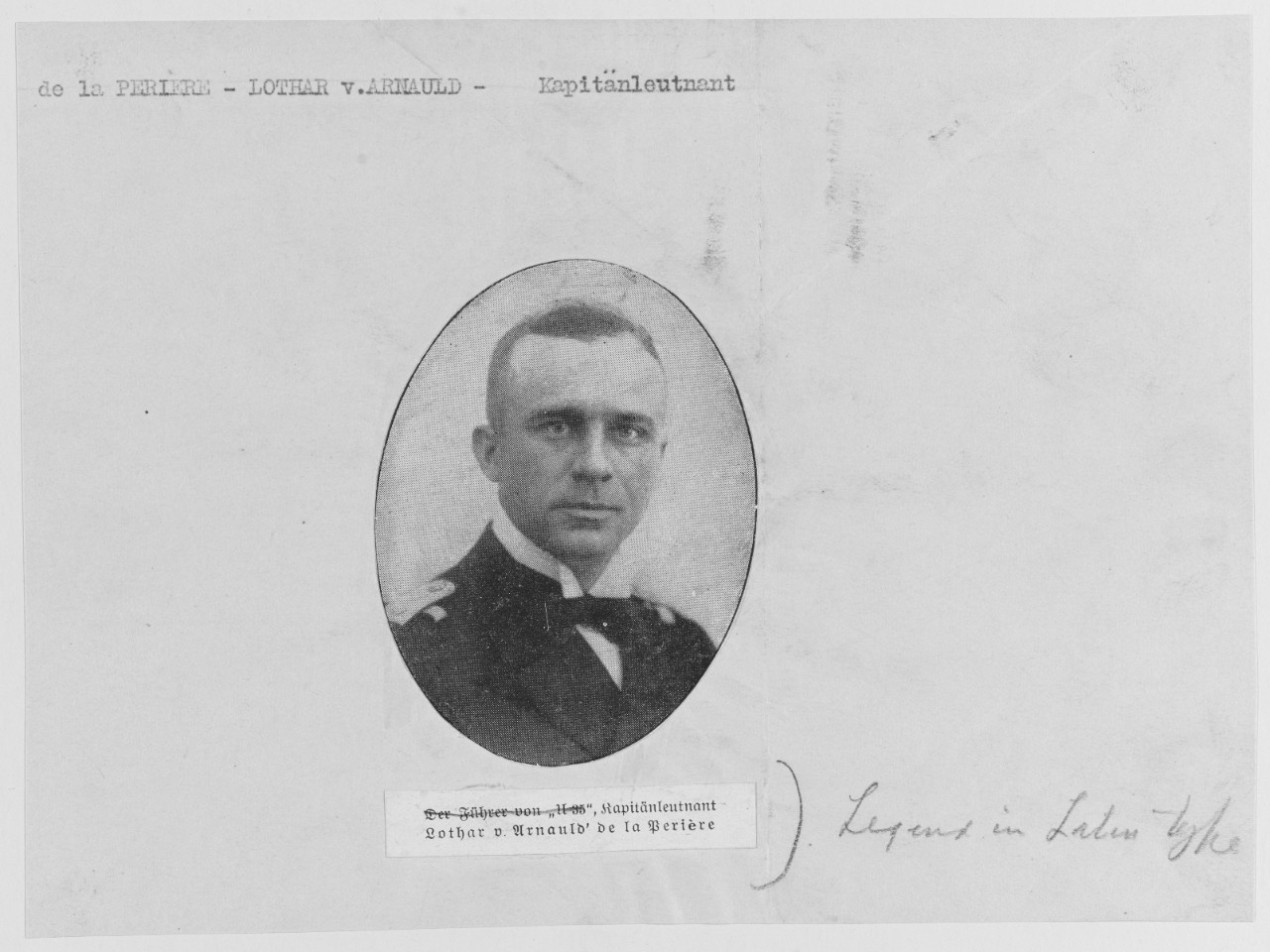

Kapitänleutnant Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière’s U-35 similarly sank the U.S.-flagged schooner Lyman M. Law in the Mediterranean on 13 February.[89] Given the manner in which both ships were sunk, neither equaled a casus belli for war with Germany, though Theodore Roosevelt, the former President, and others disagreed. These incidents did, however, prompt Wilson and the Cabinet to consider arming U.S.-flagged merchantmen. Pursuant to these discussions, Wilson asked Congress to pass the Armed Ship Bill on 26 February.[90] As he spoke, word passed through the House chamber that U-50 under Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Berger had sunk the Cunard liner RMS Laconia on its way from New York to Liverpool. Three U.S. citizens were among the 12 who perished.[91]

A further step toward war came two days later, on 28 February 1917, when President Wilson provided the text of the Zimmermann Telegram to the Associated Press. Although much of the U.S. public responded in support of Wilson’s desired armed neutrality, a good many others, including a large segment of the press, called for war. What stirred this response was Arthur Zimmermann, Germany’s new Foreign Minister, having proffered an alliance to Mexico in exchange for the promise of the latter regaining territory lost to the United States in the 19th century. Zimmermann further suggested the possibility of Japan abandoning the Entente to fight with Germany against the United States.[92]

Arthur Zimmermann (Library of Congress, LC-B2- 4069-10)

Amid the furor over Zimmermann’s note, U-62, under Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen, sank the U.S.-flagged steamer Algonquin 65 miles west of Bishop Rock on 12 March 1917. Then, in three successive days, 16–18 March 1917, German U-boats sank three additional U.S. vessels: Vigilancia by U-70 (Kapitänleutnant Otto Wunsche); City of Memphis by UC-66 (Oberleutnant Herbert Pustkuchen); and the oil tanker Illinois by UC-21 (Oberleutnant Reinhold Saltzwedel). While these four vessels were the only U.S.-registered ships among the nearly 400 ships sunk by U-boats during March, each brought the United States and Germany ever closer to war.[93] In fact, it is possible that these three ships constituted the tipping point for Wilson. He met with his Cabinet on 20 March to discuss the U.S. response.[94] The next day Wilson decided to ask for the convening of a joint session of Congress at the earliest opportunity. That date was 2 April 1917.

President Woodrow Wilson had made up his mind. Addressing Congress, he avowed:

The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.

It is a war against all nations. American ships have been sunk, American lives taken, in ways which it has stirred us very deeply to learn of, but the ships and people of other neutral and friendly nations have been sunk and overwhelmed in the waters in the same way….Armed neutrality, it now appears, is impracticable….

With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking and of the grave responsibilities which it involves, but in unhesitating obedience to what I deem my constitutional duty, I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the Imperial German Government to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States; that it formally accept the status of belligerent which has thus been thrust upon it; and that it take immediate steps not only to put the country in a more thorough state of defense but also to exert all its power and employ all its resources to bring the Government of the German Empire to terms and end the war….

The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make….

To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.[95]

President Wilson asking for a declaration of war. (LC-USZ62-113662)

Four days later, on 6 April 1917, Congress issued a joint resolution that granted Wilson’s request:

Whereas the Imperial German Government has committed repeated acts of war against the Government and the people of the United States of America; Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress Assembled, that the state of war between the United States and the Imperial German Government which has thus been thrust upon the United States is here by formally declared; and that the President be, and he is hereby, authorized and directed to employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government to carry on war against the Imperial German Government; and to bring the conflict to a successful termination all of the resources of the country are hereby pledged by the Congress of the United States.[96]

Pressed beyond its level of tolerance, much as in 1812, the United States declared war as an assertion of its rights to the freedom of the seas.

Conclusion

Wilson made freedom of the seas the second of his Fourteen Points. There, he asserted the “absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.”[97]

This principle’s legacy is that it has continued to remain a tenet of U.S. foreign policy, as evidenced by the Navy’s conduct of operations to uphold its primacy throughout the world in the decades since. This includes the conduct of neutrality patrols in the months after the outbreak of World War II, the DESOTO patrols off communist countries in the 1960s, the crossing of Libyan dictator Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s “Line of Death” into the Gulf of Sidra during the 1980s, the escorting of reflagged tankers through the Persian Gulf in 1987–88, and today’s FONOPS in the South China Sea, one of the world’s most transited waterways.[98]

To ensure the free passage of trade through these contested waters, to protect U.S. allies in the region, and to maintain forward basing there, the U.S. Navy continues to uphold the doctrine of the freedom of the seas.

─Christopher B. Havern Sr., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, October 2020

_______________________________________________

[1] Penny Campbell, “A Modern History of the International Legal Definition of Piracy,” Piracy and Maritime Crime: Historical and Modern Case Studies, eds. Bruce A. Elleman, Andrew Forbes, and David Rosenberg (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010), 20–21; James Kraska, “Grasping the Influence of Law on Sea Power,” Naval War College Review 62, no. 3 (2009), 116.

[2] Declaration concerning the Laws of Naval War. London, 26 February 1909.

[3] Arthur J. Marder, From Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919, vol. 3, The War Years: To the Eve of Jutland 1914-1916 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013). 373.

[4] Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 335.

[5] G. J. Meyer, The World Remade: America in World War I (New York: Bantam Books, 2016), 39.

[6] Interestingly, Alfred Thayer Mahan, the U.S. delegate to the conference, expressed opposition to the declaration, believing it undermined the principles of the exercise of naval supremacy.

[7] Nicholas A. Lambert, Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 142.

[8] Ibid, 175.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Meyer, World Remade, 39.

[11] Lambert, Planning Armageddon, 237.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid, 372

[14] “It is a well-settled principle of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence that the law will not permit a thing to be done indirectly which cannot legally be done directly. The application of this proposition to International Law has given rise to what is known as the doctrine of continuous voyages. Originating in the decisions of English prize courts, the principle was chiefly applied and developed in the admiralty courts of Great Britain and the United States until it became a recognized part of International Law in governing the rights of neutrals to trade with belligerents in time of war.” –“The Doctrine of Continuous Voyages, St. Louis Law Review 1, issue 3 (January 1916).

[15] Thomas A. Bailey and Paul B. Ryan, The Lusitania Disaster: An Episode in Modern Warfare and Diplomacy (New York: The Free Press, 1975), 29. Ostensibly a warning of the danger from German mines sown in the area, the declaration conveniently provided cover for the Royal Navy’s own extensive mining operations in support of the blockade. See Lawrence Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare in World War I: The Onset of Total War at Sea. (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), 15.

[16] Lawrence Sondhaus, The Great War at Sea: A Naval History of the First World War. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 137.

[17] Nicholas A. Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1999).

[18] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 12.

[19] Paul G. Halpern, “‘Handelskrieg mit U-Booten’: The German Submarine Offensive in World War I,” in Commerce Raiding: Historical Case Studies, 1755–2009, eds. Bruce Elleman and S. C. M. Paine (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2013), 138

[20] The ship did not sink, but at least 30 passengers went overboard and drowned. Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 14.

[21] Ibid, 15–16.

[22] Halpern, “Handelskrieg,” 138.

[23] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 30.

[24] “Prize rules” or “cruiser rules” are colloquial references to the conventions regarding the attacking of a merchant ship by an armed vessel. In this instance cruiser is meant in its original meaning of a ship sent on an independent mission such as commerce raiding. Cruiser rules, therefore, govern when it is permissible to open fire on an unarmed ship and the treatment of the crews of captured vessels. These rules essentially state that an unarmed vessel should not be attacked without warning. The vessel can be fired on only if it repeatedly fails to stop when ordered to do so or resists being boarded by the attacking ship. The armed ship may only intend to search for contraband when stopping a merchantman. If so, the ship may be allowed on its way, as it must be if it is flying the flag of a non-belligerent, after removal of any contraband. However, if it is intended to take the captured ship as a prize of war, or to destroy it, then adequate steps must be taken to ensure the safety of the crew. This would usually mean taking the crew on board and transporting them to a safe port. It is not usually acceptable to leave the crew in lifeboats. This can only be done if they can be expected to reach safety by themselves and have sufficient supplies and navigational equipment to do so. Alexander Gillespie, A History of the Laws of War, vol. 1, The Customs and Laws of War with Regards to Combatants and Captives (Oxford: Hart, 2011), 174.

[25] Strict Accountability Warning, 10 February 1915, http://firstworldwar.com/source/wilsonwarningfeb1915.htm.

[26] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 26.

[27] Ibid, 31.

[28] Ibid, 35.

[29] Bryan, a populist Democrat who was defeated four times as a candidate for the presidency, was a pacifist.

[30] Halpern, “Handelskrieg,” 141.

[31] Sondhaus, Great War at Sea, 143.

[32] The three earlier German attacks involving American shipping or American loss of life were the sinking of Falaba on 28 March with one American casualty, the bombing of the tanker Cushing by a German airplane on 28 April, and the torpedoing of the tanker Gulflight by U-30 on 1 May with the loss of three lives. Ibid., 150–51.

[33] Protest over the Lusitania Sinking, The Secretary of State to the Ambassador in Germany, 13 May 1915, FRUS 1915, Supplement, The World War, Document 575; https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1915Supp/d575.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Jagow issued an apology on 1 June 1915 and offered to make restitution.

[36] The Ambassador in Germany (Gerard) to the Secretary of State, 28 May 1915, FRUS 1915, Supplement, The World War, Document 615, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1915Supp/d615.

[37] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 44.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Bailey and Ryan, Lusitania Disaster, 245. See also Sondhaus, The Great War at Sea, 158: “The aftermath of the [Lusitania] sinking did find the United States drawing closer to the Allies in general and the British in particular, in part because Wilson (in contrast to Bryan) refused to keep the British on a par with the Germans once the Germans started the unrestricted U-boat campaign, and in part because the Allies, over the summer of 1915, grew to appreciate their own growing dependence on American resources. Ultimately, even when the United States protested what it considered to be British violations of international law at sea, the obvious difference was that these protests concerned damage to American economic interests rather than the death of American citizens, and thus generated fewer newspaper headlines with far less impact on US public opinion.”

[40] The Secretary of State ad interim to the Ambassador in Germany (Gerard), FRUS 1915, Supplement, The World War, Document 632, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1915Supp/d632.

[41] The Secretary of State to the Ambassador in Germany (Gerard), 21 July 1915, FRUS, 1915, Supplement, The World War, Document 692, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1915Supp/d692.

[42] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 47.

[43] Sondhaus, Great War at Sea, 153–54.

[44] Justus D. Doenecke, Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America’s Entry into World War I (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2011), 116–18.

[45] Believing U-27 to have been the U-boat that sank Arabic, Herbert and his crew did not attempt to save the survivors. In fact, they took no prisoners and fired on the German survivors.

[46] Bailey and Ryan, Lusitania Disaster, 50–52. Lusitania, it should be noted, also flew U.S. colors during her final crossing.

[47] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 75. The progressive Senator Robert La Follette (R, Wisconsin) accused Wilson of applying a double standard in dealing with Britain and Germany in this period. See Meyer, World Remade, 194-9.

[48] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 49. This is also known as the Arabic Pledge.

[49] Ibid, 50. OHL was the highest command echelon of German Army (Heer).

[50] Halpern, “Handelskrieg,” 141.

[51] Jan S. Breemer, Defeating the U-boat: Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010), 20.

[52] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 51.

[53] This was something that critics like former President Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood had advocated since the war’s outbreak.

[54] George T. Davis, A Navy Second to None: The Development of Modern American Naval Policy (Boston: Harcourt Brace, 1940), 213.

[55] Wilson to Daniels, July 21, 1915, Josephus Daniels Papers, Library of Congress.

[56] Davis, Second to None, 213.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Paul E. Pedisich, Congress Buys a Navy: Politics, Economics, and the Rise of American Naval Power, 1881–1921 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016), 221. See also George W. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890–1990 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), 59.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid, 59–60.

[61] The increase in the Army was for 142,000, the Navy 83,000, and the Marine Corps 13,000 (along with 400,000 reservists). Ibid. In his address, Wilson stated, “The programme to be laid before you contemplates the construction within five years of ten battleships, six battle cruisers, ten scout cruisers, fifty destroyers, fifteen fleet submarines, eighty-five coast submarines, four gunboats, one hospital ship, two ammunition ships, two fuel oil ships, and one repair ship.” This totals 186 ships. Arthur S. Link, ed., Papers of Woodrow Wilson, vol. 35, 7 December 1915 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966–1994).

[62] Wilson had long advocated for increasing the size and capacity of the U.S. Merchant Marine. See Jeffrey J. Safford, Wilsonian Maritime Diplomacy, 1913–1921 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1978).

[63] Davis, Second to None, 216–18. The tour included nine cities, beginning in New York on 27 January 1916 and ending in St. Louis on 3 February.

[64] Ibid, 227.

[65] The Battle of Jutland was the largest naval battle in history to that point. The Germans attempted to win a strategic victory over the Royal Navy but were unable to do so despite sinking more ships.

[66] Baer, One Hundred Years, 60.

[67] Pedisich, Congress Buys a Navy, 222.

[68] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 60.

[69] 1914–1918 Online: The International Encyclopedia of the First World War, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/sussex_pledge, hereafter 1914–1918 Online.

[70] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 64-65.

[71] 1914–1918 Online, ibid.

[72] G. J. Meyer, A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914–1918 (New York: Delacorte, 2006), 275; Avner Offer, The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989).

[73] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 87.

[74] “Gott strafe England” is the phrase in German, translating to “May God punish England.”

[75] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 102.

[76] Ibid, 103. Interestingly, it was Holtzendorff whose opposition to the first round of USW had been crucial to ending it in September 1915. Sondhaus, Great War at Sea, 242.

[77] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 103.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Sondhaus, Great War at Sea, 170.

[80] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 95–98.

[81] Sondhaus, Great War at Sea, 247.

[82] Address of the President of the United States to the Senate, 22 January 1917, FRUS 1917, Supplement 1, The World War, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1917Supp01v01/d22.

[83] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 111.

[84] Doenecke, Nothing Less than War, 252.

[85] Address of the President of the United States to Congress, 3 February 1917, FRUS 1917, Supplement 1, The World War; https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1917Supp01v01/d100.

[86] These German ships were interned as a matter of international law. As ships flagged by Germany, a belligerent nation, they could not remain in a U.S. port beyond a specified period of time. When they failed to depart U.S. ports within that timeframe, the ships were taken into a protective custody so that they could not engage in acts of war. With the severing of relations, however, it was within the rights of the U.S. to seize the ships. These particular vessels would be converted for U.S naval service after the 6 April 1917 declaration of war against Germany.

[87] Doenecke, Nothing Less than War, 256. The Navy converted these vessels into troop transports for the crossing of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to France.

[88] Rodney Carlisle, Sovereignty at Sea: U.S. Merchant Ships and American Entry into World War I (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009), 77–78.

[89] Ibid, 82–83.

[90] Ibid, 89–90, 93.

[91] Doenecke, Nothing Less Than War, 266–67.

[92] British intelligence intercepted this missive and provided it to the U.S. government in the hope that it might prompt just such a response. For more information on the Zimmermann Telegram, see Thomas Boghardt, The Zimmermann Telegram: Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America’s Entry into World War I (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2012).

[93] Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare, 114.

[94] Carlisle, Sovereignty at Sea, 106–7, 120.

[95] Address of the President of the United States Delivered at a Joint Session of the Two Houses of Congress, 2 April 1917, FRUS 1917, Supplement 1, The World War, Document 231, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1917Supp01v01/d231.

[96] Joint Resolution Declaring that a State of War Exists Between the Imperial German Government and the Government and the People of the United States and Making Provision to Prosecute the Same, Ch. 1, 40 Stat. 1, 6 April 1917, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/digitized-books/world-war-i-declarations/united-states.php.The vote in favor was 82–6 in the Senate on 4 April and 373–50 in the House of Representatives on 6 April.

[97] Address of the President of the United States Delivered at a Joint Session of the Two Homes of Congress, FRUS 1918, Supplement 1, The World War, Volume I, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1918Supp01v01, 8 January 1918.

[98] On 27 October 2015, the Arleigh Burke–class guided missile destroyer USS Lassen (DDG-82) navigated to within 12 nautical miles of the emerging land masses in the contested, but Chinese-claimed, Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. In the years since, U.S. ships have undertaken a series of “Freedom of Navigation Operation” (FONOPS) at irregular intervals because, as Michael Peck recently wrote, “Chinese air, missile, and radar bases in the disputed South China Sea enable Beijing to project military power as far away as Singapore, Vietnam and Indonesia.” Continuing, he remarked that the South China Sea “rich in energy resources and located near busy shipping lanes, has been disputed for decades. China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Indonesia and Malaysia all have competing claims on the area, while the U.S. is loath to let China control waters dear to so many American allies.” The major benefit to China “is the ability to monitor all activity in the South China Sea and support forward deployment of coast guard and militia ships who can rapidly respond to any activities by the Southeast Asian parties that China doesn’t like” and that is “slowly pushing the Southeast Asians out of these waters.” If that strategy continues to work as well as it has been, “China will control the South China Sea in a few years without having to fire a shot. And it will undermine any support for U.S. forward presence.” Michael Peck, “This Map Explains How Chinese Bombers and Missiles Control the South China Sea,” Forbes.com, 20 August 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelpeck/2020/08/20/this-map-shows-how-chinese-bombers-and-missiles-control-the-south-china-sea/#7117782121e9

Additional Reading

Ensuring the Lifeline to Victory: Antisubmarine Warfare, Convoys, and Allied Cooperation in European Waters During World War II, by Christopher B. Havern Sr.