Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Forts Jackson and St. Philip

Louisiana

16–28 April 1862

The Federal fleet under the command of Admiral David Farragut passing Forts Jackson and St.Philip. Ships identified on the print include USS Hartford, USS Mississippi, and CSS Manassas. This engraving by Harley was originally published in Loyall Farragut'sThe Life of David Glasgow Farragut: First Admiral of the United States Navy, Embodying his Journal and Letters (New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co, 1879). (Naval History and Heritage Command [NHHC], NH 1075)

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

Flag Officer David Farragut, United States Navy (USN)

Commander David Porter, USN

General Benjamin Butler, United States Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Major General Mansfield Lovell, Confederate States Army (CSA)

Brigadier General Johnson Duncan, CSA

Colonel Edward Higgins, CSA

Captain William Whittle, CSN

Commander John Mitchell, CSN

BACKGROUND

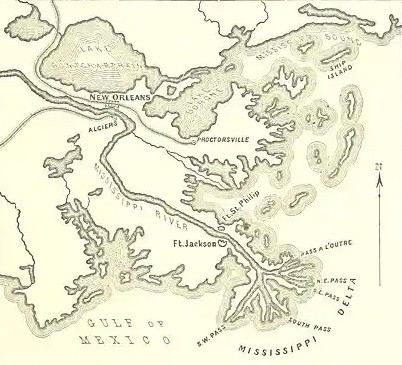

In 1860, New Orleans was one of the largest port cities in North America. Almost one hundred miles south of the city, the Mississippi River enters the Gulf of Mexico. Before the river intersects with the Gulf, its main stem splits at a point known as the Head of Passes. Four distinct channels pass through the delta region: Pass à l’Outre, the Northeast Pass, South Pass, and the Southwest Pass.

Approximately 25 miles above Head of Passes and 75 miles below New Orleans, two forts protected the southern approach to the port city. On the eastern bank, Fort St. Philip predated the War of 1812. Both forts had external water batteries to extend their range over the river. On 10 January 1861, Louisiana militia seized both forts on orders from the state’s governor.[1] Later that month, members of the state legislature voted for Louisiana to become the sixth state to declare its secession from the United States. From the start of this conflict, New Orleans became a target for the U.S. armed forces. Not only was the city the largest in the new confederacy, its location made its occupation essential if the U.S. government hoped to regain total control of the Mississippi River.

In 1862, there were four different approaches, or passes, through the Mississippi delta to New Orleans. This map is from Charles C. Coffin, Drum-Beat of the Nation: The First Period of the War of the Rebellion from Its Outbreak to the Close of 1862 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1888), 241.

PRELUDE

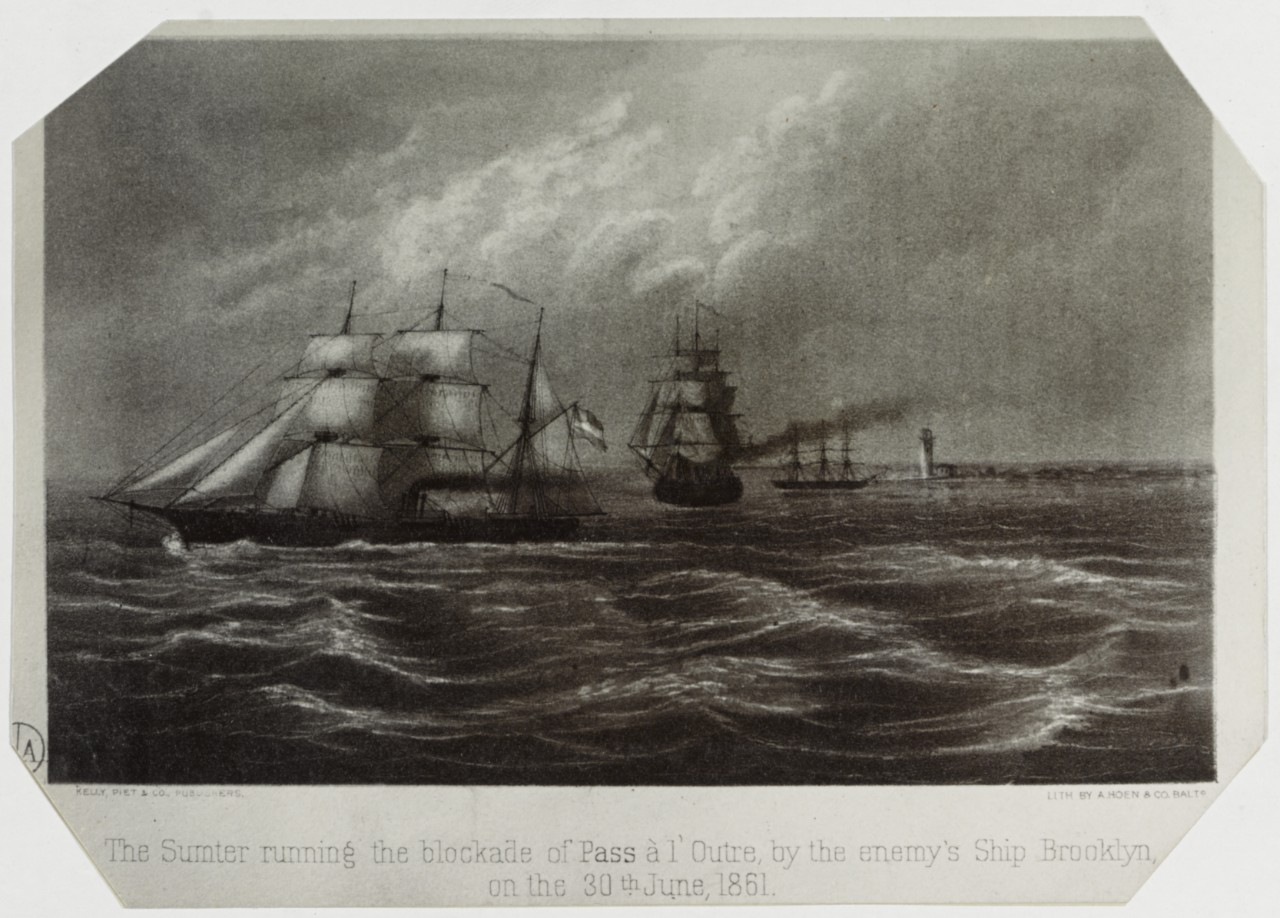

When President Abraham Lincoln announced his intent to blockade the southern states, the U.S. Navy lacked both the numbers and the strength to establish an effective blockade. As one of the major ports along the Gulf Coast, New Orleans was a priority despite the scarcity of ready ships. At the end of May, Flag Officer William Mervine, in command of the Gulf Blockading Squadron, sent two ships to blockade the mouth of the Mississippi. USS Brooklyn, commanded by Commander Charles H. Poor, took a position at the Pass à l’Outre,[2] the deepest of the channels leading into the mouth of the river. USS Powhatan, commanded by Lieutenant David D. Porter, went to the Southwest Pass,[3] the other major entrance to the river. On 30 June, the Navy vessels had their first close encounter with an enemy ship when CSS Sumter managed to run past Brooklyn.[4] Two ships were simply too few to seal the port. The effectiveness of the blockade was further hampered by the steam-powered ships’ need for coal and their position at the end of the U.S. Navy’s supply chain into the Gulf of Mexico.

The U.S. Navy’s ad hoc committee that came to be known as the Blockade Strategy Board first met on 27 June 1861. Their first three reports focused on the Atlantic coast. Their fourth report, dated 9 August, discussed the importance of New Orleans. Analyzing the various approaches and the defenses surrounding the city, the board recommended against any attempt at attacking the city, preferring to reinforce the blockade and seal off the port. They encouraged the capture of Ship Island, off the coast in the Gulf of Mexico, as a naval depot for the blockaders.[5]

On 30 June, Sumter escaped into the Gulf of Mexico while Brooklyn was away from its station at Pass à l’Outre.[6]

“The Sumter running the blockade of Pass à l’Outre, by the enemy's ship Brooklyn, on the 30th June, 1861,” lithograph, A. Hoen and Company, Baltimore, Maryland. This illustration was originally printed in Raphael Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States (Baltimore, MD: Kelly, Piet, and Co., 1869). (NHHC, NH 51797)

This incident and other failures within the operational area of the Gulf Blockading Squadron became a source of frustration for Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles.[7] Welles ultimately sought new leadership for the Gulf squadron, replacing Mervine with Flag Officer William W. McKean. Immediately after the change of command, McKean started issuing orders to improve the efficiency of the blockade of the Mississippi River.[8] Within two weeks of the change of command, U.S. Navy vessels under command of Captain John Pope—Richmond, Vincennes, Preble, and Water Witch—occupied the Head of Passes.[9] Their presence did not go unnoticed. Commodore George N. Hollins, the commander of the Confederate naval forces afloat at New Orleans, began to plan an attack to push back at the blockade.

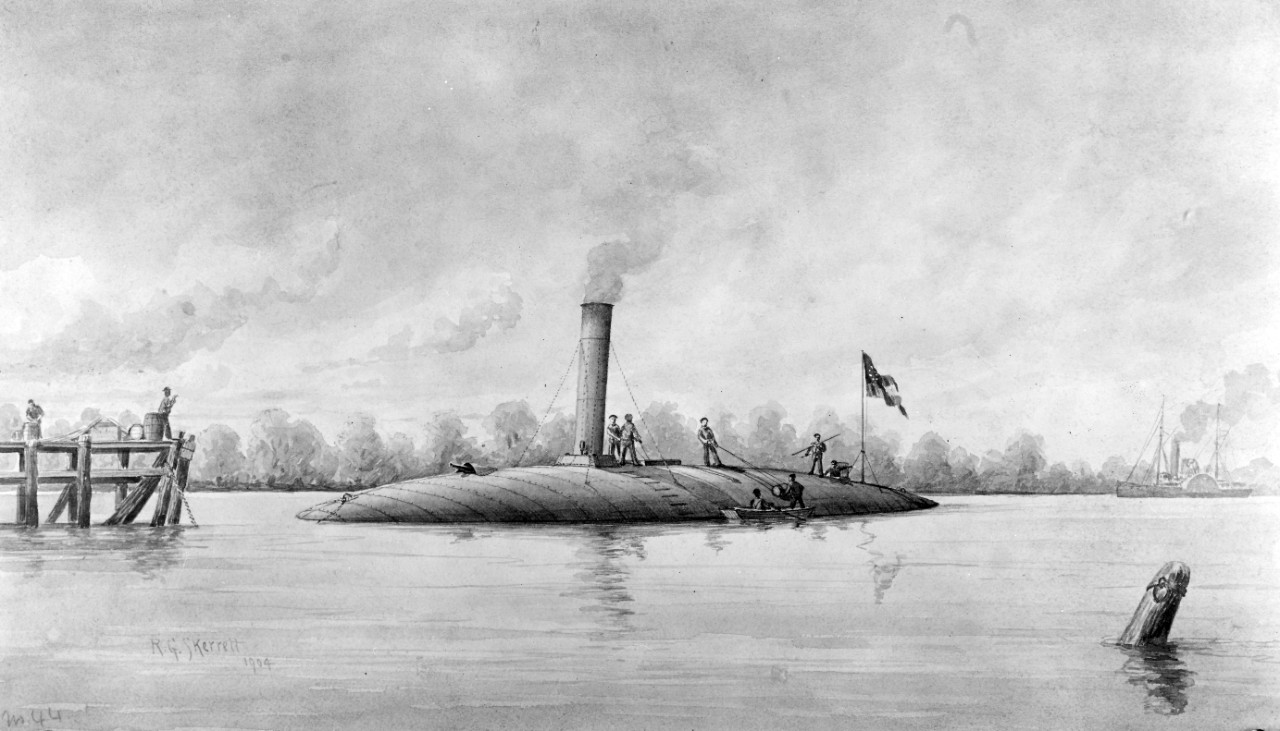

Skerrett, R.G.,"CSS Manassas," sepia wash drawing, 1904. (NHHC, NH 608)

On the night of 11–12 October, the Confederate ironclad ram Manassas led an attack on the Federal blockading force at Head of Passes. Although the ironclad suffered almost as much damage as it inflicted during the encounter, its attack on Pope’s flagship, USS Richmond, was only the beginning of the attack. CSS Tuscarora, CSS McRae, and CSS Ivy followed closely behind the ironclad, pushing three fire rafts chained together. The combined effect of the ironclad and the fire rafts was enough to drive the Federal ships back from the Head of Passes. The blockade remained in place at the delta, but the Head of Passes was once again under Confederate control. It was becoming more apparent that any hope of completely sealing off the port of New Orleans required holding a position farther upriver.

In early November, Porter approached Welles, and later President Lincoln, with an idea for attacking and capturing New Orleans. Lincoln approved the plan, but Porter was viewed as too young to take command of such an operation. Instead Welles appointed Flag Officer David G. Farragut, and Porter was charged with outfitting a semi-independent flotilla of mortar schooners to accompany Farragut’s force.

In January 1862, Farragut officially received command of the new West Gulf Blockading Squadron of 24 gunboats augmented by Porter’s mortar flotilla. At the end of the month, he headed south for New Orleans aboard his flagship, Hartford. With the constitution of the squadron, the War Department started to amass land support for Farragut’s expedition. General Benjamin Butler received orders to occupy Ship Island, recently abandoned by the Confederate forces.

While Farragut amassed his squadron at Ship Island, the Confederate forces originally assigned to New Orleans were slowly being drawn away. After the fall earlier that year of Forts Henry and Donelson, which guarded the confluence of the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers, General Mansfield Lovell, in command of the defenses at New Orleans, received orders to send reinforcements north to Tennessee. As the Western Gunboat Flotilla descended the Mississippi River, Hollins was frequently called upon to send his vessels upriver to offer afloat support to the Confederate army. When Hollins himself had to go north, the Confederate secretary of the navy appointed two men, Commander William C. Whittle and Commander John K. Mitchell, to split his responsibilities in New Orleans.

In April, once the southbound ironclad Federal gunboats had reduced and passed Island No. 10 near New Madrid, Missouri, Hollins asked permission to return to New Orleans. When he received news of the Federal fleet crossing the bar into the Mississippi’s main channel, he made a decision to not await a response.[10] Mallory subsequently sent orders for Hollins to remain upriver, but Hollins disregarded these.[11] Hollins was subsequently relieved of his command upon his return to New Orleans and recalled to Richmond.[12]

In New Orleans in April 1862, the contingent of the Confederate States Navy was the most powerful of three separate organizations afloat off New Orleans. It included three ironclads, CSS Manassas, Louisiana, and Mississippi; and two converted gunboats, McRae and Jackson. Louisiana and Mississippi had the potential to bring a good deal of firepower into the upcoming fight, but they remained unfinished. The Louisiana Provisional Navy provided two ships, General Quitman and Governor Moore, for the city’s defenses. Finally, the River Defense Fleet, nominally controlled by the Confederate States Army, had six “cotton-clad” rams: Warrior, Stonewall Jackson, Defiance, Resolute, General Lovell, and General Breckinridge.[13] Captain John A. Stephenson, in command of the River Defense Fleet, refused to accept the orders of Commander Mitchell even though he had received specific instructions to do so from General Lovell. Lovell was becoming increasingly concerned that neither the Confederate navy nor the two other afloat contingents seemed willing to cooperate with him.[14] Without their cooperation, he repeatedly wrote to his leadership, he was concerned that his department was being “drained of everything.”[15] However, in the spring of 1862, Confederate leaders looking at the western theater remained focused on the actions in the upper Mississippi River valley rather than on the approaching threat from the Gulf of Mexico.

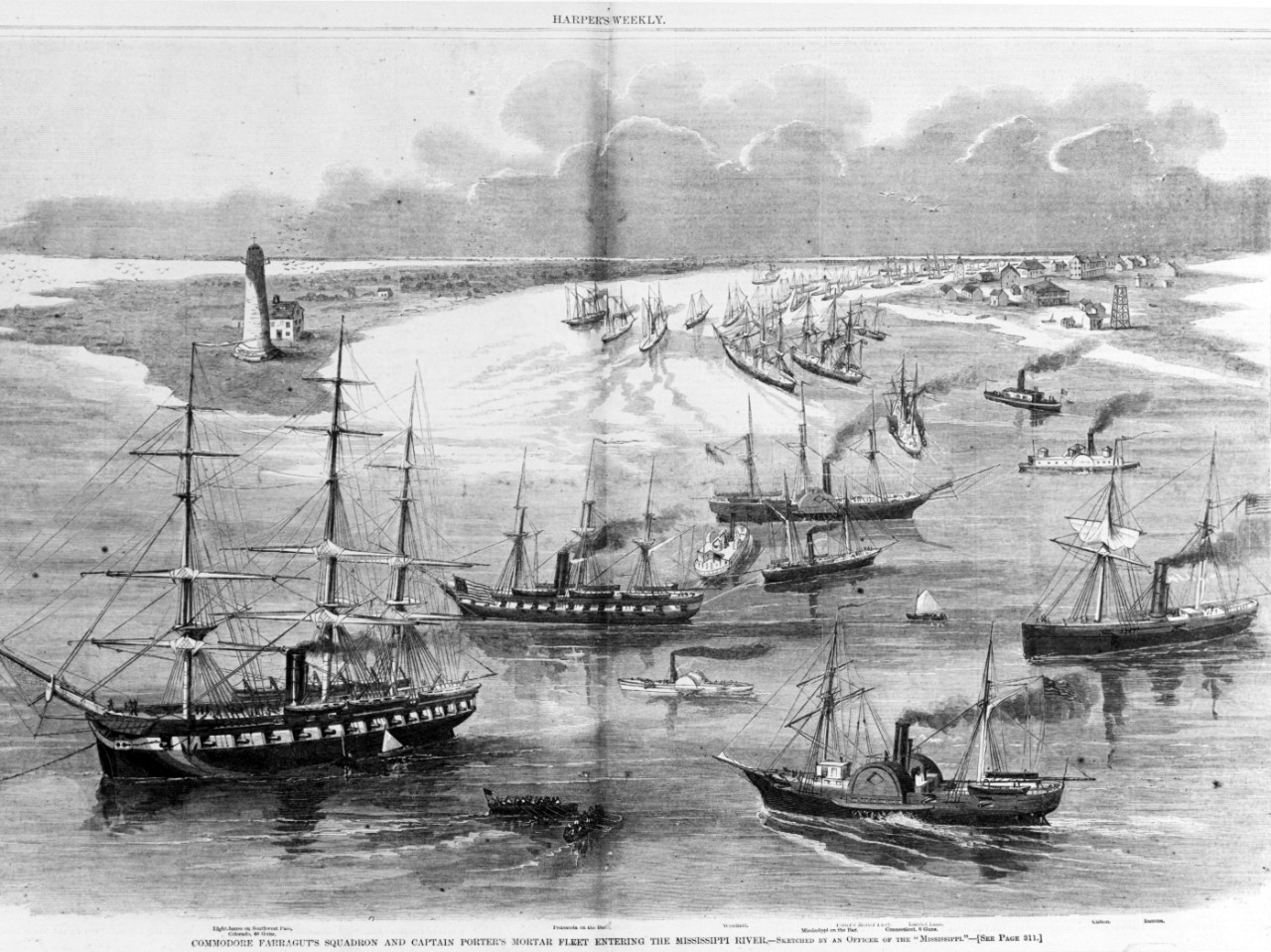

On 18 March, Farragut’s squadron arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi River. The smaller gunboats and the mortar schooners were able to cross the bar into the main shipping channel at Pass à L’Outre. However, the low water level (only 15 feet) and a lack of pilots familiar with the channels required that the deeper-draft vessels be lightened and pulled across the bar to enter the Southwest Pass. This process took almost a month to complete. One ship, Colorado, was unable to cross the bar. While Porter’s force waited for the rest of the fleet, he sent scouting parties and surveyors upstream. This interval allowed time for Porter to gauge the strength of the forts, to determine the range of the defenders’ guns, and to position the mortar schooners for the fight to come. As the Federal fleet began its preparations, there was little that Lovell could do against this new threat at this point except hope that the forts below the city would be able to maintain the defense of their bend in the river.

Admiral Farragut's squadron and Captain Porter's mortar fleet entering the Mississippi River at the Southwest Pass in April 1862. This engraving was based on a sketch by an officer of USS Mississippi, and originally published in Harper's Weekly, 7 April 1862. (NHHC, NH 59059)

BATTLE

On 18 April, Porter’s flotilla commenced its bombardment of Forts Jackson and St. Philip at 0900. During this first phase of engagement, all 19 mortar schooners fired long range into the forts. They focused most of the attention on Fort Jackson due to its proximity and its size. It was also Porter’s belief that if Fort Jackson surrendered, Fort St. Philip would not stand alone.[16] Positioned behind a curve in the river and camouflaged by the trees, it was difficult for the garrisons at the forts to return fire on the mortar schooners. The question remained whether the bombardment from Porter’s flotilla would be enough to force a surrender.

Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan, in command of both forts, quickly sought the support of the Confederate navy. On 20 April, Commander Whittle reluctantly designated the unfinished ironclad Louisiana as a floating battery to be placed above the forts in the river.[17] Duncan requested that the ironclad be positioned further downstream, but Louisiana’s captain, Commander Charles F. McIntosh, explained that the ship’s unfinished condition, especially its lack of steam power, did not allow the vessel to be placed directly under enemy fire. The ironclad was present only to prevent the further intrusion of the enemy if their vessels passed the forts.[18]

Although the return fire from the forts continued to fall short of the mortar fleet, the bombardment was not doing enough damage to replicate the success of the November 1861 Federal bombardment of Port Royal, South Carolina. Farragut grew impatient and started preparing for the next phase of the attack. Reconnaissance of the forts and the approach to New Orleans had revealed a boom, a defensive chain of hulks (sunken decommissioned ships), stretched across the river just below the forts.[19] On 20 April, Farragut ordered three of his Unadilla-class gunboats (Kineo, Itasca, and Pinola) forward to break the chain across the river below the forts. This task did not prove to be easy.

Three days later, the crews of the three gunboats had managed to open a small gap in the barrier. Although the evolution had not been as successful as Farragut had hoped, this gap would allow the ships to pass in single file. This narrow opening required Farragut to adjust his original plan of attack, which had included two columns passing the forts simultaneously, one column engaging with Fort Jackson and the other with Fort St. Philip. Farragut continued to adjust his plan according to the changing conditions, but he sent out a general order to prepare to pass the forts.

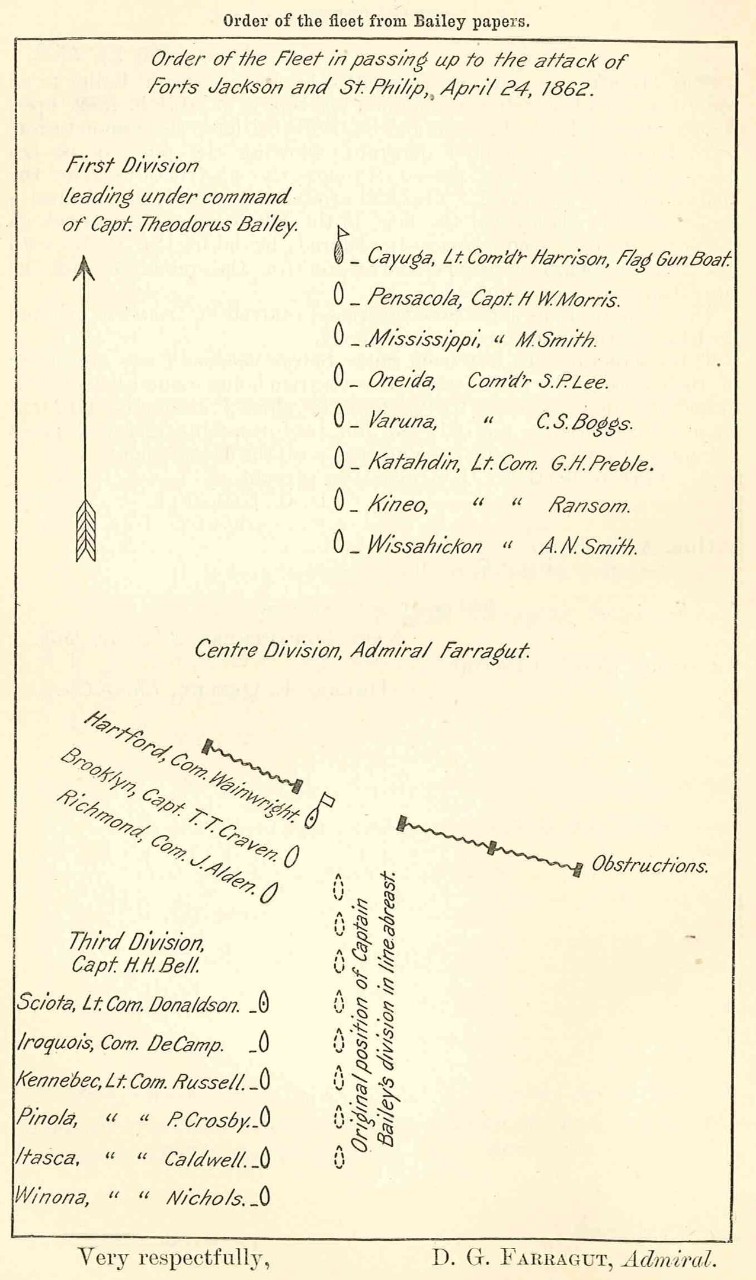

The order of the advance of the Federal fleet preparing to pass Forts Jackson and St. Philip, in April 1862, endorsed by Farragut. Originally printed in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series I, Volume 18, Government Printing Office, 1904), page 166.

Beginning at 0200 on 24 April, Farragut took advantage of the darkness to get past the broken barrier and, while still unseen, as close to the forts as possible. He organized his 17 ships into three divisions.

The first division, under the command of Captain Theodorus Bailey included Cayuga, Pensacola, Mississippi, Oneida, Varuna, Katahdin, Kineo, and Wissahickon.

The second division comprised of Farragut’s own flagship, Hartford, along with Brooklyn and Richmond.

The third division, under Captain Henry H. Bell, consisted of three gunboats—Sciota, Iroquois, Kennebec, Pinola, Itasca, and Winona.

Although the organization of the maneuver had changed twice already, the general concept was the same: pass single file through the gap while avoiding the return fire from the forts and engage the afloat enemy above the forts.

At 0345, the forts began to fire upon the first division passing under their guns. Cayuga, Bailey’s flagship, was the first to pass the forts at 0400 and the first to engage with the Confederate fleet waiting above the forts.[20] In the ensuing confusion, the first ships in Bailey’s division were able to get past the Confederate fleet before these were able to get underway.[21] As more ships from Bailey’s division passed the forts, it became a challenge distinguishing between friend and foe, especially as the smoke from the exchange of fire began to fill the air.

“The Splendid Naval Triumph on the Mississippi, April 24th, 1862: Destruction of the Rebel Gunboats, Rams, and Iron Clad Batteries by the Union Fleet under Flag Officer Farragut,” c. 1862, lithograph, Currier and Ives. (NHHC, NH 76369-KN)

The last of the ships from the first division mingled with Farragut’s heavy warships, but all remained afloat and continued forward through the gap. All of the U.S. Navy vessels were forced to dodge fire rafts as they moved upriver. Most of the Confederate defensive efforts seemed to be directed at the heaviest warships of Farragut’s division.[22] The Confederate steam tug Mosher pushed a fire raft alongside Hartford, but quick thinking on the part of its crew saved the Federal warship from the blaze.

The third and final division under Bell was caught by heavy fire as the rising sun exposed its position. Fourteen of the seventeen gunboats ultimately made it past the forts, with the exception of three of the six ships in the third division. In the melee of the opposing naval forces that followed the passing of the forts, the U.S. Navy lost one vessel and the Confederate forces lost twelve, including the ironclad Manassas.

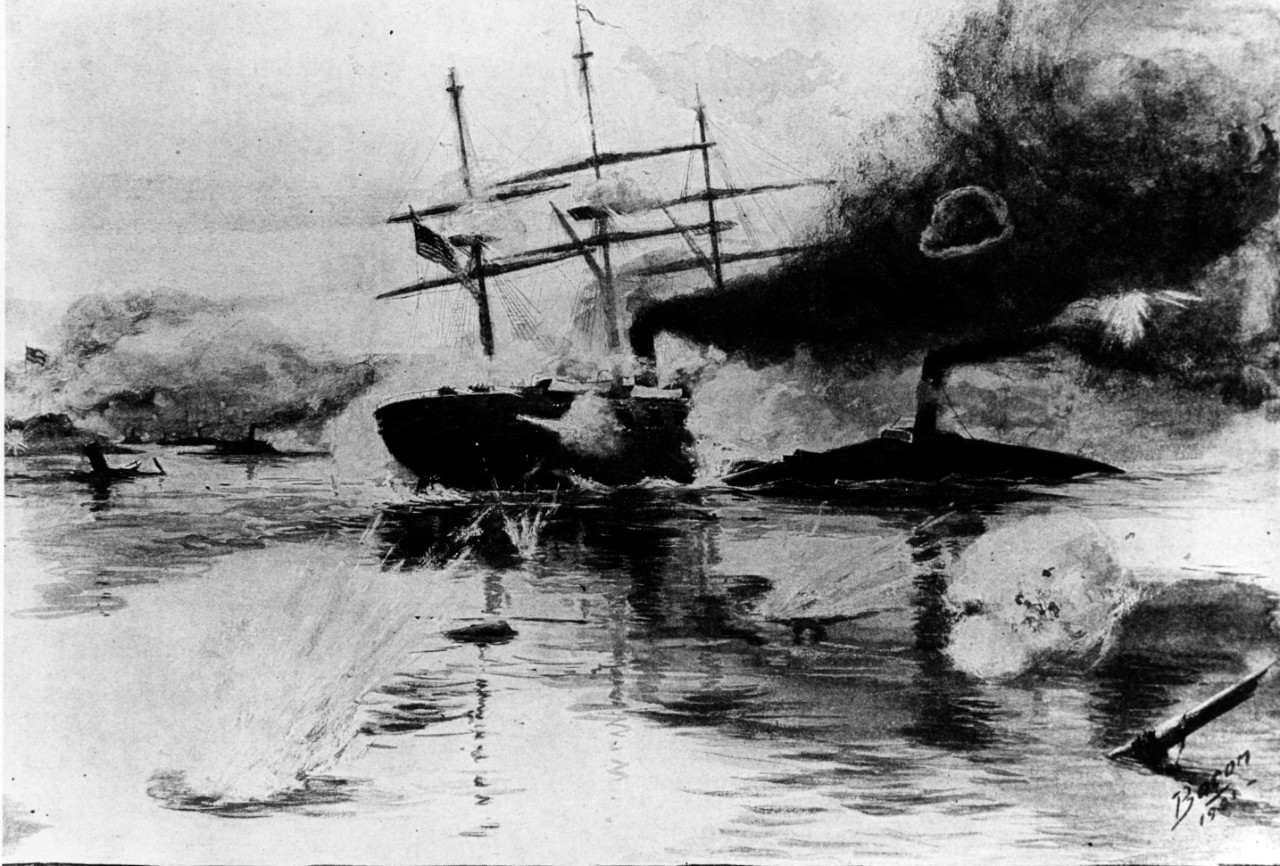

Irving R. Bacon, “The Manassas struck us a Diagonal Blow,” painting, c. 1907. This painting depicts CSS Manassas ramming into USS Brooklyn during the battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, on the Mississippi River below New Orleans on 24 April 1862. This illustration was originally published in Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keyel, Deeds of Valor, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Perrien-Keydel Company, 1907). (NHHC, NH 79908)

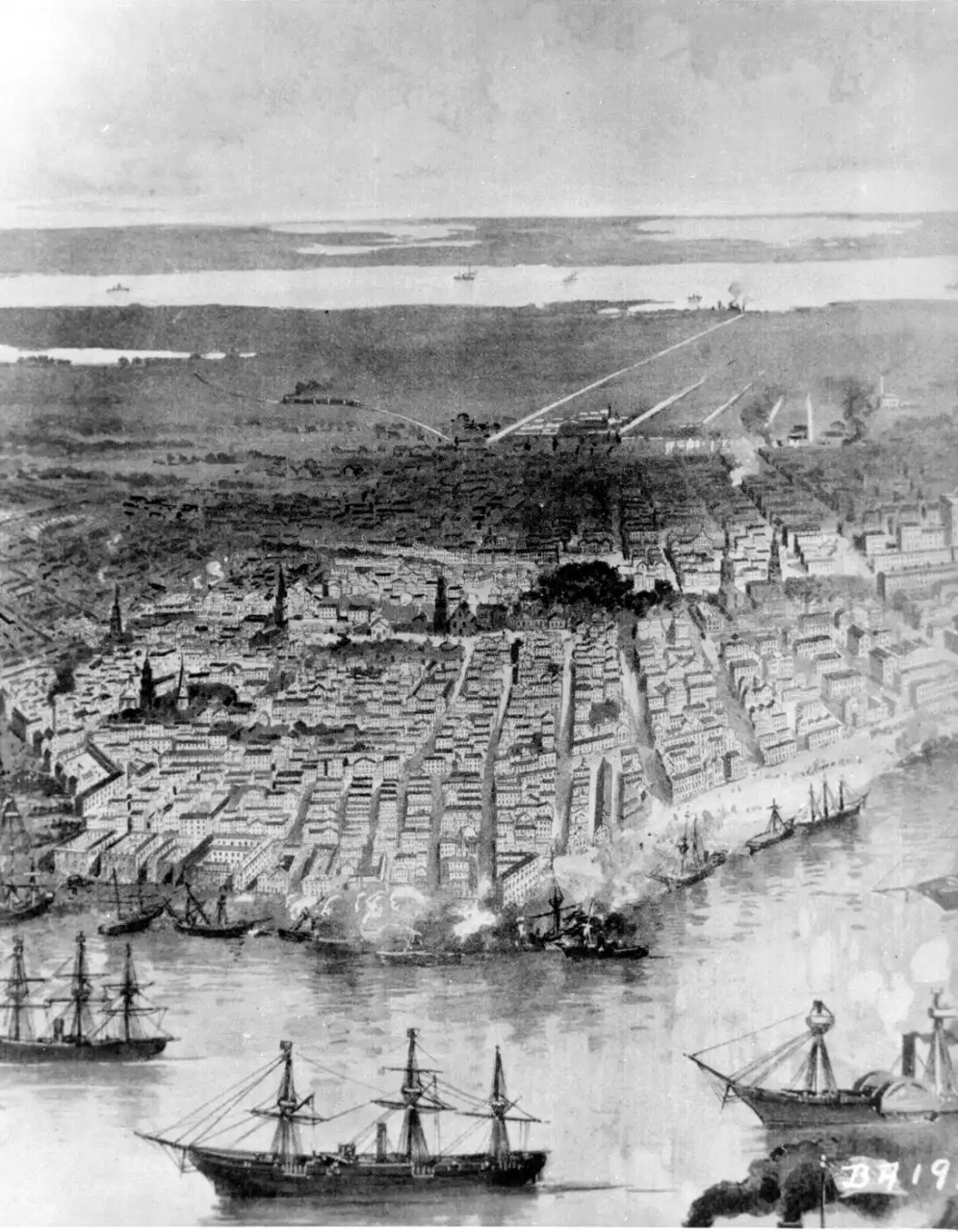

After passing the forts, Farragut did not wait to continue attacking the forts from the rear.[23] Anchoring on the night of 24 April by 1800, the fleet was underway next morning. The inner ring of fortifications closer to New Orleans had not been intended to resist a naval force operating on the Mississippi River.[24] The batteries at Chalmette were quickly silenced.[25] On the afternoon of 25 April, Farragut anchored his ships off New Orleans. Captain Bailey was sent to demand the surrender of the city. General Lovell had already evacuated the troops from the city, so it lacked any defense against the U.S. Navy’s guns. The last of the unfinished ironclads, CSS Mississippi, was burned rather than be surrendered. The mayor and the city council attempted to negotiate terms. Three days later, Farragut sent a contingent ashore to run up the U.S. flag at the custom house rather than continue to await their surrender.[26]

The battle for the forts was not over after Farragut’s ships passed up the river. Porter continued his bombardment in preparation for a land assault by Butler’s soldiers. After Farragut’s fleet had passed the forts, Butler had assumed that Farragut’s fleet would wait for the army before continuing to New Orleans.[27] His troops landed on the Gulf-side crossing in the rear of Fort St. Philip to reach the river. By the time the soldiers made it through the swamps to the landward side of the fort, Farragut’s fleet had continued up the river to New Orleans rather than support an assault on Fort St. Philip. Butler was disappointed with Farragut’s decision because he was unable to bring his troop transports to New Orleans until the forts had been reduced or had surrendered. Although he had brought scaling ladders to assault the rear of Fort St. Philip, he made no further attempt to do so.

On the night of 27-28 April, the garrison at Fort Jackson mutinied.[28] Although this action did not directly affect Fort St. Philip, the incident and the interdependent nature of the two forts ultimately forced General Duncan to arrange the surrender of both forts to Porter. Commander Mitchell subsequently set CSS Louisiana afire and adrift rather than surrender it.

The U.S. Navy had performed a singular service in the passing of the forts and the surrender of the city of New Orleans. The representatives of the U.S. Army involved in the campaign bore witness to its triumph, but it was the U.S. naval officers Farragut and Porter who accepted the surrender of the enemy.

“Panoramic View of New Orleans-Federal Fleet at Anchor in the River,” c. 1862. This illustration is from Rossiter Johnson, Campfires and Battlefields (New York: Williams and Cox Co., 1894). (National Archives and Records Administration, 530501)

AFTERMATH

On 1 May 1862, Butler and the U.S. Army took responsibility for the occupation of New Orleans. While Farragut and Butler solidified their control of the Mississippi delta, the Western Gunboat Flotilla descended the river from Island No. 10 to Memphis, Tennessee.[29]

Farragut ascended the Mississippi River with his squadron to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He received the surrender of Baton Rouge and Natchez before heading for Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. The Federal victory at Memphis in June allowed the Western Gunboat Flotilla to descend to Vicksburg and rendezvous with Farragut in July 1862.[30]

A year later, the city of Vicksburg was under siege by combined U.S. forces under command of General Ulysses S. Grant and Commander David D. Porter. The Federal occupation of New Orleans opened the way for a convergence on Vicksburg that wrestled control of the Mississippi River from the Confederacy.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

Admiral Farragut and Captain Percival Drayton on the deck of the U.S. frigate, Hartford, c. 1861–1865. (Library of Congress, 2013646182)

NHHC Resources:

Flag-Officer David G. Farragut and the Capture of New Orleans

Additional Resources

New Orleans in the Civil War, American Battlefield Trust.

“New Orleans Gone and with it the Confederacy”–The Fall of New Orleans, Emerging Civil War.

The Confederate Navy’s Order of Battle at New Orleans, Emerging Civil War.

Capture of New Orleans: Farragut’s Rise to Fame, The Mariners’ Museum and Park.

The Defense of New Orleans, 1718-1900, National Park Service.

Further Reading

Bielski, Mark F. A Mortal Blow to the Confederacy: The Fall of New Orleans. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2021.

Hearn, Chester G. The Capture of New Orleans, 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995

Pierson, Michael D. Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

***

NOTES

[1] United States War Department, The War Of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies [hereafter referenced as ORA], Series 1, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1880), 491.

[2] Civil War Naval Chronology, 1861-1865 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office [GPO], 1971), 15.

[3] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion [hereafter referenced as ORN], Series 1, Vol. 4 (Washington: GPO, 1896), 188-89.

[4] ORN, Ser. 1, 1 (1894): 34.

[5] ORN, 1, 16:627–28.

[6] ORN, 1, 16:569.

[7] Gideon Welles, The Diary of Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy under Lincoln and Johnson (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), Vol. 1, 76.

[8] ORN, 1, 16:685.

[9] ORN, 1, 16:700.

[10] ORN, 1, 22:839.

[11] ORN, 1, 22, 840.

[12] Read more: Neil P. Chatelain, “George N. Hollins’ Fall from Grace,” Emerging Civil War, 24 April 2022.

[13] Cottonclads were an innovative type of steam-powered wooden vessel “armored” with cotton bales for protection from enemy fire.

[14] ORN, 1, 18:255, 844–45.

[15] ORN, 1, 2:684.

[16] ORN, 1, 18:437.

[17] Louisiana, Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 26 September 2023.

[18] ORN, 1, 18:323.

[19] ORN, 1, 8:89

[20] ORN, 1, 18:173.

[21] Neil P. Chatelain, Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861-1865 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020), 161.

[22] Chatelain, 165.

[23] ORN, 1, 18:158.

[24] ORN, 1, 18: 142.

[25] ORN, 1, 18: 221.

[26] ORN, 1, 18: 154.

[27] ORA, 1, 6:713-14.

[28] Read more: Michael D. Pierson, Mutiny at Fort Jackson: The Untold Story of the Fall of New Orleans (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

[29] The Western Gunboat Flotilla was renamed the Mississippi River Squadron on 1 October 1862 after its transfer from the U.S. Army to the U.S. Navy.

[30] Flag Officer Charles H. Davis succeeded Andrew H. Foote as commander of the Western Gunboat Flotilla in May 1862.