Texas II (Battleship No. 35)

1914-1948

The second U.S. Navy ship named for the 28th State of the Union.

II

(Battleship No. 35: displacement 27,000 tons; 1ength 573'0"; beam 95'2½" (water line); draft 29'7"; speed 21.05 knots (trial); complement 954; armament 10 14-inch guns, 21 5-inch guns, 4 3-pounders, 4 21-inch torpedo tubes (submerged); class New York)

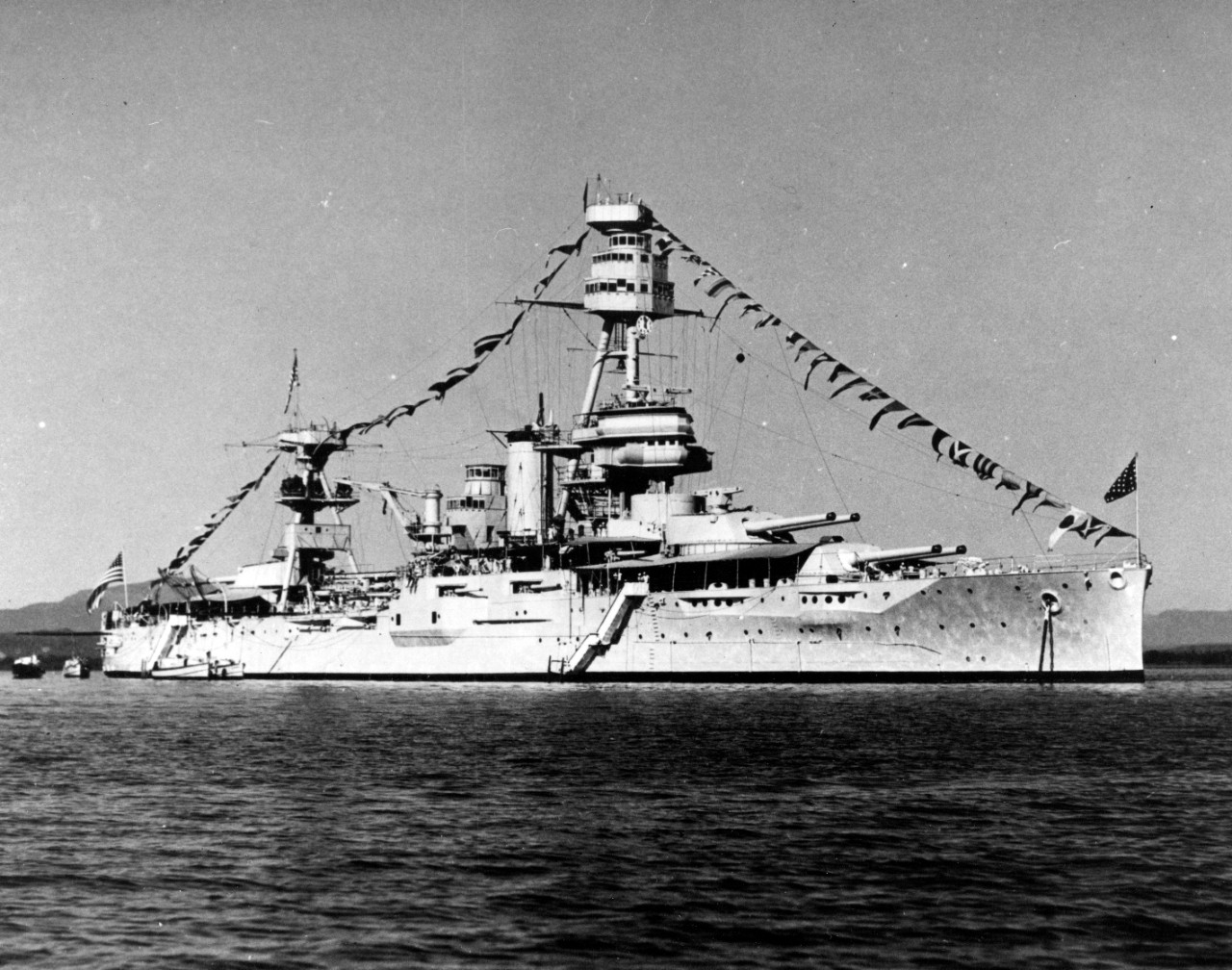

The second Texas (Battleship No. 35) was laid down on 17 April 1911 at Newport News, Va., by the Newport News Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 18 May 1912; sponsored by Miss Claudia Lyon; and commissioned on 12 March 1914, Capt. Albert W. Grant in command.

On 24 March 1912, Texas departed the Norfolk Navy Yard and, after a stop at Hampton Roads, set a course for New York. She made an overnight stop at Tompkinsville, N.Y., on the night of the 26th and 27th and entered the New York Navy Yard on the latter day. She spent the next three weeks there undergoing the installation of the fire control equipment.

During her stay in New York, President Woodrow Wilson ordered a number of ships of the Atlantic Fleet to Mexican waters in response to tension created when an overzealous detail of Mexican Federal troops detained a U.S. boat crew at Tampico. The problem was quickly resolved locally, but Rear Adm. Henry T. Mayo sought further redress by demanding an official disavowal of the act by the Huerta regime and a 21-gun salute to the U.S. flag.

Unfortunately for Mexican-American relations, President Wilson apparently saw in the incident an opportunity to put pressure on a government he felt undemocratic. On 20 April 1914, Wilson placed the matter before Congress and sent orders to Rear Adm. Frank Friday Fletcher, commanding the naval force off the Mexican coast, instructing him to land a force at Veracruz and to seize the customs house there in retaliation for the incident at Tampico. That action was carried out on the 21st and 22nd.

Due to the intensity of the situation, when Texas put to sea on 13 May 1914, she headed directly to operational duty without benefit of the usual shakedown and post-shakedown repair period. After a five-day stop at Hampton Roads (14-19 May), she joined Rear Adm. Fletcher’s force off Veracruz on the 26th. She remained in Mexican waters for just over two months, supporting the American forces ashore. On 8 August, she left Veracruz and set course for Nipe Bay, Cuba, and thence steamed to New York where she entered the Navy Yard on 21 August.

The battleship remained there until 5 September 1914 when she returned to sea, joined the Atlantic Fleet, and settled into a schedule of normal fleet operations. In October, she returned to the Mexican coast. Later that month, Texas became station ship at Tuxpan, a duty that lasted until early November. The ship finally bade Mexico farewell at Tampico on 20 December and set a course for New York. The battleship entered the New York Navy Yard on 28 December and remained there undergoing repairs until 16 February 1915.

Upon her return to active duty with the fleet, Texas resumed a schedule of training operations along the New England coast and off the Virginia capes alternated with winter fleet tactical and gunnery drills in the West Indies. That routine lasted just over two years until the February-to-March crisis over unrestricted submarine warfare catapulted the U.S. into war with the Central Powers in April 1917.

The 6 April 1917 declaration of war found Texas riding at anchor in the mouth of the York River with the other Atlantic Fleet battleships. She remained in the Virginia capes-Hampton Roads vicinity until mid-August conducting exercises and training naval armed-guard gun crews for service on board merchant ships.

In August 1917, she steamed to New York for repairs, arriving at Base 10 on the 19th and putting in to Long Island Sound on the 20th. She entered the New York Navy Yard soon thereafter. She completed repairs on 26 September and got underway for Port Jefferson that same day.

During the mid-watch on the 27th, however, she ran hard aground off Block Island. For three days, her crew lightened ship to no avail. On the 30th, tugs came to her assistance, and by 6:06 a.m. on 2 October, Texas was afloat again. Six tugs moved the battleship away from those waters, but hull damage dictated a return to the yard, and the extensive repairs she required precluded her departure with Division 9 for the British Isles in November.

By December 1917, she had completed repairs and moved south to conduct war games out of the York River. Mid-January 1918 found the battleship back at New York preparing for the voyage across the Atlantic. She departed New York on 30 January; arrived at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland on 11 February; and rejoined Division 9, by then known as the Sixth Battle Squadron of Britain's Grand Fleet.

Texas’ service with the Grand Fleet consisted entirely of convoy missions and occasional forays to reinforce the British squadron on blockade duty in the North Sea whenever German heavy units threatened. The fleet alternated between bases at Scapa Flow and at the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Texas began her mission only five days after her arrival at Scapa Flow where she sortied with the entire fleet to reinforce the Fourth Battle Squadron, then on duty in the North Sea. She returned to Scapa Flow the next day and remained until 8 March when she put to sea on a convoy escort mission from which she returned on the 12th. Texas and her division mates entered the Firth of Forth on 12 April but got underway again on the 17th to escort a convoy. The U.S. battleships returned to base on 20 April. Four days later, Texas again stood out to sea to support the Second Battle Squadron the day after the German High Seas Fleet had sortied from Jade Bay toward the Norwegian coast to threaten an Allied convoy. Forward units caught sight of the retiring German ships on the 25th but at such extreme range that no possibility of bringing the enemy to battle existed. The Germans returned to their base that day, and the Grand Fleet, including Texas, did likewise on the next.

Texas and her division mates passed a relatively quiescent May of 1918 in the Firth of Forth. On 9 June, she got underway with the other warships of the Sixth Battle Squadron and headed back to the anchorage at Scapa Flow, arriving there the following day. Between 30 June and 2 July, Texas and her colleagues acted as escort for American minelayers adding to the North Sea mine barrage. After a two-day return to Scapa Flow, Texas put to sea with the Grand Fleet to conduct two days of tactical exercises and war games. Leaving Scapa Flow on the 11th, the fleet stood in to the Firth of Forth the following day.

For the remainder of the World War, Texas and the other battleships of Division 9 continued to operate with the Grand Fleet as the Sixth Battle Squadron. With the German Fleet increasingly more tied to its bases in the estuaries of the Jade and Ems Rivers, the U.S. and British ships settled more and more into a routine schedule of operations with little or no hint of combat operations. That state of affairs lasted until the armistice ended hostilities on 11 November 1918. On the night of 20 and 21 November, she accompanied the Grand Fleet to meet the surrendering German Fleet. The two fleets rendezvoused about 40 miles east of May Island -- located near the mouth of the Firth of Forth -- and proceeded into the anchorage there.

Subsequently, the American contingent moved to Portland, England, arriving there on 4 December 1918. Eight days later, Texas put to sea with Divisions 9 and 6 to meet President Wilson, embarked in the troop transport George Washington (Id. No. 3018) on his way to the Paris Peace Conference. The rendezvous took place at about 7:30 a.m. the following morning and provided an escort for the President into Brest, France, where the ships arrived at 12:30 p.m. That evening, Texas and the other U.S. battleships departed Brest for to return to the U.S. The warships arrived off Ambrose Light on Christmas Day 1918 and reached New York the following day.

Following overhaul, Texas resumed duty with the Atlantic Fleet early in 1919. On 9 March, the battleship brought on board a British-built Sopwith Camel and the next day, while lying at anchor in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, she became the first U.S. battleship to launch an airplane when Lt. Cmdr. Edward O. McDonnell flew the Camel off the platform having been constructed on the crown of Turret II. That summer, she was reassigned to the Pacific Fleet. On 17 July 1920, she was designated BB-35 during the Navy’s standardization of nomenclature and identification numbers.

Texas served in the Pacific until 1924 when she returned to the east coast for overhaul and to participate in a training cruise to European waters with Naval Academy midshipmen embarked. She entered the Norfolk Navy Yard on 31 July 1925 for a major modernization overhaul during which her cage masts were replaced with a single tripod foremast. She also received the latest in fire control equipment. Following that overhaul, she resumed duty along the eastern seaboard and kept at that task until late in 1927 when she did a brief tour of duty in the Pacific between late September and early December.

Near the end of the year, Texas returned to the Atlantic where she served as flagship of the U.S. Fleet. On 15 January 1928, she transported President Calvin Coolidge to Havana for the Pan-American conference, returning with him to Key West on the 17th. Two months later, she steamed to the Panama Canal and the west coast to maneuvers with the fleet near Hawaii.

Texas arrived at New York Navy Yard on 27 June 1928, and with the exception of a brief trip to New London, Conn. (7-11 July) remained there until 4 September. After further operations off the eastern seaboard, she returned to the New York Navy Yard for her annual overhaul (6 December 1928 – 7 January 1929), after which she proceeded back to the Pacific for a six-month stint (17 January – 11 June). She returned to the Atlantic in June and resumed normal duty with the Scouting Fleet. In April 1930, she took time from her operating schedule to escort the U.S. Lines steamship Leviathan into New York when that ship returned from Europe carrying the delegation that had represented the United States at the London Naval Conference. In January 1931, she left the yard at New York as flagship of the United States Fleet and headed via the Panama Canal to San Diego, her home port of San Pedro for the next six years. During that period, she served first as flagship for the U.S. Fleet and, later, as flagship for Battleship Division (BatDiv) 1.

In the summer of 1937, she was once more reassigned to the east coast, as the flagship of the Training Detachment, U.S. Fleet. Late in 1938 or early in 1939, the warship became flagship of the newly organized Atlantic Squadron, built around BatDiv 5. Through both organizational assignments, her labors were directed primarily to training missions, midshipman cruises, naval reserve drills, and training members of the Fleet Marine Force. These missions became more urgent following the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939.

After operating briefly in the West Indies, Texas began operating on the Neutrality Patrol in May 1941, established to keep the war out of the western hemisphere, principally basing on Narragansett Bay, making three extended cruises, in May, June, and July, into the North Atlantic. During the second of those patrols, on 20 June, Texas, in company with the destroyers Mayrant (DD-402), Trippe (DD-403) and Rhind (DD-404), was sighted by the German submarine U-203 (Kapitänleutnant Rolf Mützelburg, commanding), on her first war patrol, within what the Kriegsmarine considered the war, or “blockade” zone in the Atlantic. The U.S. ships, unaware of U-203’s being in proximity, outdistanced the U-boat and frustrated any attack plans. Consequently, Grössadmiral Erich Raeder, the Commander in Chief of the Kriegsmarine, sent orders to his deployed U-boats that U.S. ships could only be attacked if they ventured across the western boundary of the blockade zone by 20 miles or more, or within a 20-mile strip along that western boundary. Subsequently, she remained at Norfolk for a period of repairs and alterations (15 August–14 October) then a one-day sail to Argentia, Newfoundland).

Sunday, 7 December 1941, found Texas at Casco Bay, Maine, enjoying a rest and relaxation period following three months of watch duty at Argentia, Newfoundland. Receiving word there of the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific, Texas remained in Casco Bay for ten days, after which she returned to Argentia, remaining there for the holidays.

On 15 January 1942, Texas cleared Tompkinsville, N.Y., on an escort run and reached Iceland on 25 January, the transports Chateau Thierry (AP-31) and Strathaird leaving Task Force 15 on 23 January in the company of British destroyers. Texas then proceeded to operate in readiness to deal with German surface raiders. Returning home in March, the battleship resumed convoy-escort missions. On one occasion, she escorted Guadalcanal-bound Marines as far as Panama. On another, the warship screened service troops bound for Freetown, Sierra Leone, seeing the convoy to within 400 miles of the west coast of Africa. She made one trip to Great Britain prior to invasion of North Africa.

On 23 October 1942, Texas embarked upon her first major combat operation when she sortied with Task Group (TG) 34.8, the Northern Attack Group for Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa. The objective assigned to this group was Mehedia near Port Lyautey and the port itself. The ships arrived off the assault beaches early in the morning of 8 November and began preparations for the invasion. When the troops went ashore, Texas did not come immediately into action to support them. At that point in the war, amphibious warfare doctrine was still embryonic; and many did not recognize the value of a pre-landing bombardment. Instead, the Army insisted upon attempting surprise. Texas finally entered the fray early in the afternoon when the Army requested her to destroy an ammunition dump near Port Lyautey. For the next week, she contented herself with cruising up and down the Moroccan coast delivering similar, specific, call-fire missions. Thus, unlike later operations, she expended only 273 rounds of 14-inch and 6 rounds of 5-inch. During her short stay, some of her crew briefly went ashore to assist in salvaging some of the shipping sunk in the harbor. On 15 November, she departed North Africa and headed for home in company with light cruiser Savannah (CL-42), auxiliary aircraft carrier Sangamon (ACV-26), oiler Kennebec (AO-36), four transports, and seven destroyers.

Throughout 1943, Texas carried out the familiar role of convoy escort. With New York as her home port, she made numerous transatlantic voyages to such places as Casablanca and Gibraltar, as well as visits to ports in the British Isles, making one round trip in 1943 and a second that began on 29 December 1943 and ended on 23 January 1944. That routine continued into 1944 but ended in April of that year when, at the European end of one such mission, she remained at the Clyde estuary in Scotland and began training for the invasion of Normandy. That warm-up period lasted about seven weeks at the end of which she departed Belfast Lough and travelled down the Irish Sea and around the southern coast of England to arrive off the Normandy beaches on the night of 5-6 June.

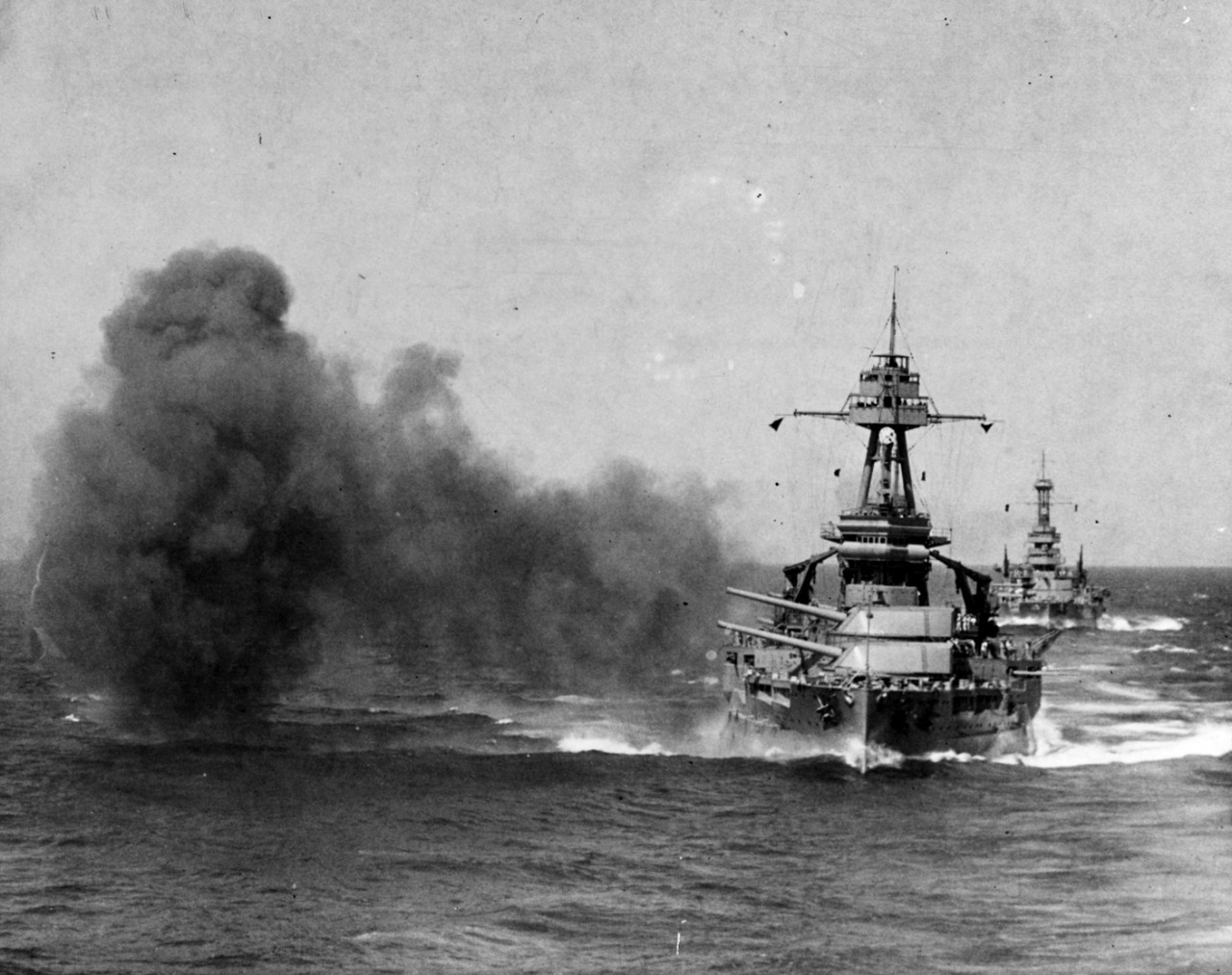

At about 0440 on the morning of 6 June 1944, Texas closed the Normandy coast to a point some 12,000 yards offshore near Pointe du Hoc. At 0550, she began churning up the coastal landscape with her 14-inch salvoes. Meanwhile, her secondary 5-inch battery went to work on another target on the western end of Omaha beach, a ravine laced with strong points to defend an exit road. Later, under control of airborne spotters, she moved her major-caliber fire inland to interdict enemy reinforcement activities and to destroy batteries and other strong points farther inland.

By noon, she closed the beach to about a range of 3,000 yards to fire upon snipers and machinegun nests hidden in a defile just off the beach. At the conclusion of that mission, the warship took an enemy antiaircraft battery located west of Vierville under fire.

The following morning, her main battery rained 14-inch shells on the enemy-held town of Trevieres to break up German troop concentrations. That evening, she bombarded a German mortar battery which had been shelling the beach. Not long after midnight, German planes attacked the ships offshore, and one of them swooped in low on Texas’ starboard quarter. Her antiaircraft batteries opened up immediately but failed to score on the intruder. On the morning of 8 June, her guns fired on Isigny, then on a shore battery, and finally on Trevieres once more.

After that, she retired to Plymouth to rearm, returning to the French coast on the 11th. From then until the 15th, she supported the Army in its advance inland. However, by the latter day, the troops had advanced beyond the range of her guns; and the battleship moved on to another mission, having expended 690 rounds of 14-inch and 272 of 5-inch in the preceding twelve days.

On the morning of 25 June 1944, Texas closed in on the vital port of Cherbourg and, with Arkansas (BB-33), opened fire upon various fortifications and batteries surrounding the town. The guns on shore returned fire immediately and, at about 1230, succeeded in straddling Texas. The battleship, however, continued her firing runs in spite of shell geysers blossoming about her. The enemy gunners proved stubborn and good. At 1316 a 240-millimeter shell slammed into her fire control tower, killed the helmsman, and wounded nearly everyone on the navigation bridge. Texas’ commanding officer, Capt. Baker, miraculously escaped unhurt and quickly had the bridge cleared. The warship herself continued to deliver her 14-inch shells in spite of damage and casualties. Some time later, another shell struck the battleship. That one, a 240-millimeter armor-piercing shell, crashed through the port bow, entered a compartment located below the wardroom, but failed to explode. Throughout the three-hour duel, the Germans straddled and near-missed Texas over 65 times, but she continued her mission until 1500 when she retired, having expended 208 rounds of 14-inch in the roughly three-hour action.

Texas steamed to Plymouth, England, where a bomb disposal team carefully removed the fuse, detonator and explosives from the unexploded shell, allowing its later presentation to the warship as a lucky charm. Following damage repairs to the battleship, Texas conducted refresher drills in preparation for the invasion of southern France. On 15 July 1944, she departed Belfast Lough and headed for the Mediterranean. After stops at Gibraltar and Oran in Algeria, the battleship sailed to Taranto, Italy, before setting a course for the Riviera coast of France. She arrived off St. Tropez during the night of 14 and 15 July. At 0444, she moved into position for the pre-landing bombardment and, at 0651, opened up on her first target, a battery of five 155-millimeter guns. Due to the fact that the troops ashore moved inland rapidly against light resistance, she provided fire support for the assault for only the first day. Texas departed the southern coast of France on the evening of 16 August, having fired 172 rounds of 14-inch and 171 of 3-inch. After a stop at Palermo, Sicily, she left the Mediterranean and headed for New York where she arrived on 14 September 1944.

At New York, Texas underwent a month-long repair period during which the barrels on her main battery were replaced. After a brief refresher cruise to Casco Bay, she departed Maine in November and set a course, via the Panama Canal, for the Pacific. She made a stop at Long Beach, Calif., and then continued on to Oahu. She spent Christmas of 1944 at Pearl Harbor and then conducted maneuvers in the Hawaiian Islands for two weeks before steaming to Ulithi Atoll. She departed Ulithi on 10 February 1945, stopped in the Marianas for two days of invasion rehearsals, and then set course for Iwo Jima. She arrived off the target on 16 February, three days before the scheduled assault. She spent those three days pounding Japanese defenses on Iwo Jima in preparation for the landings. After the troops stormed ashore on the 19th, Texas switched roles and began delivering support and call fire. She remained off Iwo Jima for almost a fortnight, helping the Marines subdue a well dug-in and stubborn Japanese garrison. The duty kept her gunners busier than ever, as the battleship fired 923 rounds of 14-inch and 967 of 5-inch between 16 and 21 February.

Texas cleared Iwo Jima on 7 March 1945 and returned to Ulithi to prepare for the Okinawa operation. She departed Ulithi with TF 54, the gunfire support unit, on 21 March and arrived off the Ryukyus on the 25th. Texas did not participate in the occupation of the islands and roadstead at Kerama Retto carried out on the 26th but moved in on the main objective instead, beginning the pre-landing bombardment that same day. For the next six days, she delivered 14-inch salvoes to prepare the way for the Army and the Marine Corps. Each evening, she retired from her bombardment position close to the Okinawan shore only to return the next day and resume her poundings. The enemy ashore, preparing for a defense-in-depth strategy as at Iwo Jima, made no answer. Only his air units provided a response, sending several kamikaze raids to harass the bombardment group. Texas escaped damage during those attacks. After six days of aerial and naval bombardment, the ground troops’ turn came on 1 April. They stormed ashore against initially light resistance. For almost two months, Texas remained in Okinawan waters providing gunfire support for the troops ashore and fending off the enemy aerial assault. In performing the latter mission, she claimed one kamikaze kill on her own and three assists. The duration and scale of the operation dwarfed any of her previous gunnery efforts, with the battleship expending 2,019 14-inch, 2,640 5-inch and 490 3-inch rounds in almost seven weeks of action. The warship even expended 3,100 40 millimeter and 2,275 20 millimeter rounds against air and shore targets.

On 14 May 1945, Texas retired to Leyte in the Philippines and remained there until after the Japanese capitulation on 15 August. She returned to Okinawa toward the end of August and stayed in the Ryukyus until 23 September. On that day, she set a course for the U.S. with troops embarked. The battleship delivered her passengers to San Pedro, Calif., on 15 October. She celebrated Navy Day there on 27 October and then resumed her mission bringing American troops home. She made two round-trip voyages between California and Oahu in November and a third in late December.

On 21 January 1946, Texas departed San Pedro and steamed via the Panama Canal to Norfolk where she arrived on 13 February and soon began preparations for inactivation. In June, she was moved to Baltimore, Md., where she remained until the beginning of 1948. Texas was towed to San Jacinto State Park in Texas where she was decommissioned on 21 April 1948 and turned over to the state of Texas to serve as a permanent memorial. Her name was stricken from the Navy Register on 30 April 1948.

Texas (BB-35) earned five battle stars during World War II.

Updated 7 September 2017