Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Operation Vittles@75

At the conclusion of World War II, the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union divided and occupied all of Germany, but its capital city was still highly contested. Initially, U.S., U.K., and French troops controlled western portions of Berlin, while the Soviet Union occupied the eastern sector. As the wartime alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union began to sour and friendly relations turned into a Cold War, the question of whether the western occupation zones in Berlin would remain under Allied control or whether the city would be absorbed into Soviet-controlled eastern Germany was of primary importance.

On June 24, 1948, 75 years ago, Soviet forces blockaded rail, road, and water access to Allied-controlled areas of Berlin. Two days later, the Berlin Airlift, codenamed Operation Vittles, was initiated, and the United States and United Kingdom responded to the Soviet blockade by airlifting food and fuel to Berlin from Allied airbases in western Germany. In perspective, the future of postwar Germany was plagued by political divisions between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. The only decision of significance that emerged was the agreement of zones of occupation. Even after the end of hostilities, the problem of what to do about Germany was never successfully addressed at the July–August 1945 Potsdam Conference. Not only was there a lack of consistency with the political leadership, occupation policy on the ground also confronted unforeseen challenges. Two and a half million residents of Berlin, spread between four zones of occupation, faced profound hardships—Allied bombing had reduced the city to rubble, shelter and warmth were infrequent, the black market dominated the city’s economic life, and starvation loomed.

After it was decided to employ all available aircraft to supply the city by air, U.S, Army Gen. Lucius Clay, commander of U.S. Occupation Forces and military governor of the U.S. Zone of Germany, reported he could meet the summertime needs of Berlin with an airlift of 3,500 tons a day, but that coal shipments required for winter heating would increase the amount needed to 4,500 tons a day. On Sept. 10, Clay requested 116 additional Douglas C-54 Skymaster aircraft—69 to be made available by Oct. 1 and the remaining 47 by Dec. 1, 1948—so that he could build up a stockpile of supplies for the winter months. In response to his request, Washington decided to augment the Berlin Airlift with only 50 additional C-54s. Two weeks after his initial request for additional support, Clay strongly reiterated his need for the full 116 aircraft package. After conducting a thorough reappraisal of U.S. objectives in Berlin, Clay’s request was finally approved by the Joint Chiefs of Staff for an immediate reinforcement, and, on Oct. 22, President Harry S. Truman gave final approval for the expansion of the airlift by granting the additional C-54s that Clay wanted.

This is where the Navy became fully involved in the Berlin Airlift. Although Navy tankers had been delivering massive quantities of aviation fuel to Bremerhaven, Germany, to furnish fuel for the airlift since the beginning of the blockade, its planes had not been involved in the aerial supply effort. The new increase that was called for would bring the use of C-54s in the airlift up to approximately 52 percent of the total number of such aircraft in the country’s operational inventory—thus seriously eroding the Air Force’s emergency war plans. Due to his concerns, Air Force Secretary Stuart Symington asked Navy Secretary John Sullivan to provide three Navy squadrons to the Airlift Task Force as part of the latest augmentation. The Navy readily agreed to the request.

On Oct. 27, 1948, in concurrence with Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Louis Denfeld, Transport Squadrons VR-6 and VR-8 were assigned to 180 days of temporary duty with the Airlift Task Force for participation in Operation Vittles. Both squadrons, at the time, were stationed in the Pacific. In addition to the two Pacific squadrons, a third squadron was added to provide transatlantic support from the U.S. East Coast. As operations commenced, the Navy squadrons quickly made their presence known to their Air Force counterparts. Winter weather in Germany proved extremely difficult for all the squadrons engaged in the airlift, due to heavy fog banks blanketing Berlin. It was routine during these months for the aircraft to fly east and west through the air corridor on instruments and to make ground control approaches at both Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport and Rhein-Main Air Force Base. Fortunately for Navy planes, their crews were, on average, more skilled in instrument flying than were the Air Force crews. During the first two weeks of flying the air route from Rhein-Main to Tempelhof, the two squadrons carried a total of 6,526 tons of cargo. By the end of December 1948, VR-8 was leading all squadrons in the airlift in every measurable phase of air transport operations, including aircraft utilization, total cargo carried, payload efficiency, and tons per plane. VR-6 was not far behind, being engaged for several weeks in a battle for second place with the two top Air Force squadrons. By the end of February 1949, VR-6 was equaling and frequently exceeding VR-8 in operational achievements. During April 1949 alone, the two squadrons flew a combined total of 8,234 hours and delivered 23,550 tons of food and coal to Berlin.

After several months of negotiations, the Soviet Union finally agreed to end the blockade of Berlin, but only if the three Western powers agreed to terminate their restrictions on trade with East Germany and East Berlin. On May 5, 1949, the four governments announced that the blockade would end on May 12. During the months that VR-6 and VR-8 operated in Germany, their aircraft flew 45,990 hours, carrying 129,989 tons of cargo into Berlin and averaging 10.1 flight hours per plane per day. For more on the Navy’s humanitarian mission, visit NHHC’s website.

Women’s Armed Services Integration Act@75

After World War II, approximately 86,000 women served in the U.S. Navy as nurses or in the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) under the provisions of the Naval Reserve Act of 1938. Congress amended the act on July 30, 1942, which established the Women’s Reserve Program. In 1947, the Army-Navy Nurses Act established the Nurse Corps as permanent staff corps of the Navy and Army, granting nurses’ permanent commissioned rank. On June 12, 1948, 75 years ago, President Harry S. Truman signed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act into law. The law granted women the right to serve as permanent members of the U.S. Armed Services. The number of women who could serve was capped at 2 percent of all personnel and prohibited women’s participation in combat units and flying in combat. For the first time after the passage of the act, women were permitted to serve alongside men in the military. Despite the magnitude of this decision, recruitment was initially slow. In June 1950, only 3,200 women were on active duty; however, the outbreak of the Korean War sparked an increase in recruitment efforts.

Capt. Joy Bright Hancock, former director of the WAVES, was instrumental in the passage of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act. Hancock leveraged her decades of experience in the Navy to advocate for women’s permanency. On July 7, 1948, the first six enlisted women were sworn into the regular Navy: Chief Yeoman Wilma J. Marchal; Yeoman Second Class Edna E. Young; Hospital Corpsman First Class Ruth Flora; Aviation Storekeeper First Class Kay L. Langen; Storekeeper Second Class Frances T. Devaney; and Teleman Doris R. Robertson. On Oct. 15, 1948, Hancock and seven other women were sworn in as officers: Lt. Cmdr.’s Winifred Quick Collins, Ann King, and Frances Willoughby; Lt.’s Ellen Ford and Doris Cranmore; and Lt.’s (j.g.) Doris Defenderfer and Betty Rae Tennant.

Before women became a permanent part of the armed forces, they had supported the U.S. military for generations. During the American Revolution and the War of 1812, women were mostly responsible for cooking, laundry services, and assisting with medical services. They also provided general supplies, intelligence on enemy positions, and the procurement of gunpowder. During the Civil War, women served as nurses and so-called “sanitary agents.” Some women even dressed as men and fought alongside them. Dr. Mary Walker was a contract surgeon for the Army during the Civil War and is the only woman to be awarded the Medal of Honor to date.

World War I brought new challenges in terms of the labor force. To keep men in the fight and not behind a desk, the Navy admitted women on the home front into ranks such as Yeoman (F), who initially performed clerical duties, but their duties expanded to include other stateside contributions, including service as radio operators, electricians, and pharmacists. During World War II, the armed services expanded dramatically for women with approximately 350,000 women serving during the war. In the Korean conflict, about 120,000 women served on active duty, some working as nurses while others filled professional roles such as engineers. During the Vietnam War, women again served in active duty roles in a growing variety of occupational specialties. More recently, 37,000 women were deployed in support of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm, and nearly 300,000 were deployed in support of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom.

In 2013, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta announced that women would be allowed to serve in combat roles, and by 2015, the plan to allow women more occupational choices within the military had been implemented. Today, women serve in all branches of the military and are no longer banned from serving in direct combat.

“Angel of the Orient”: First Hospital Ship off Vietnam

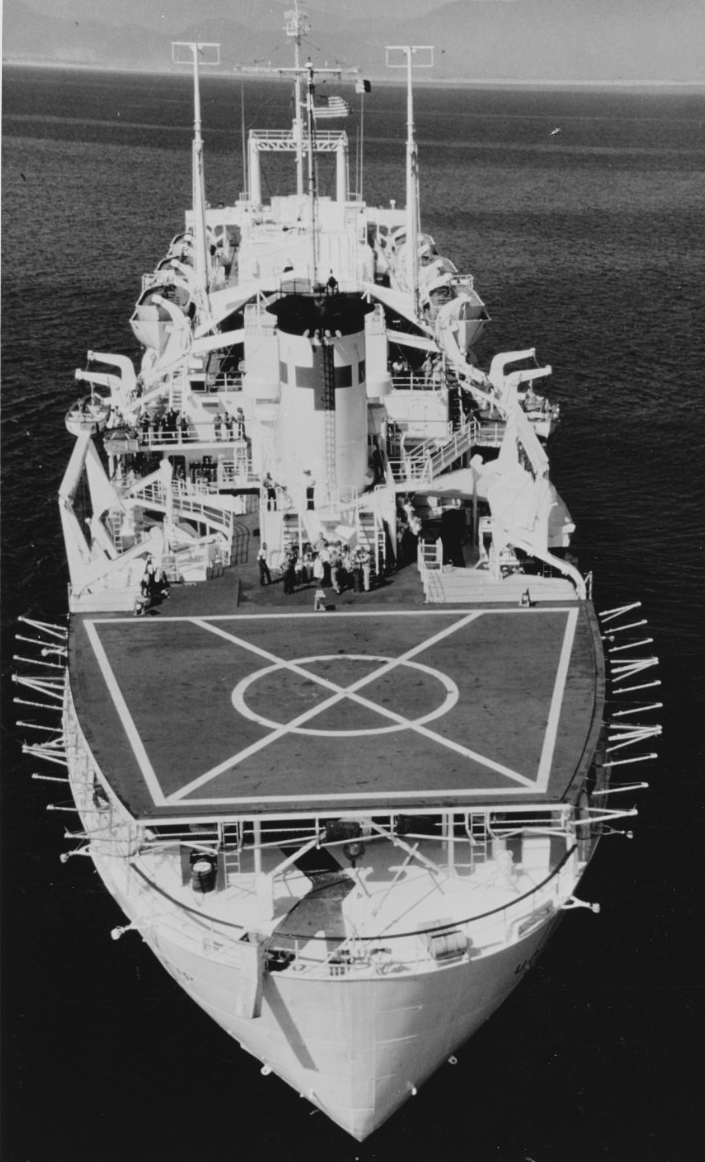

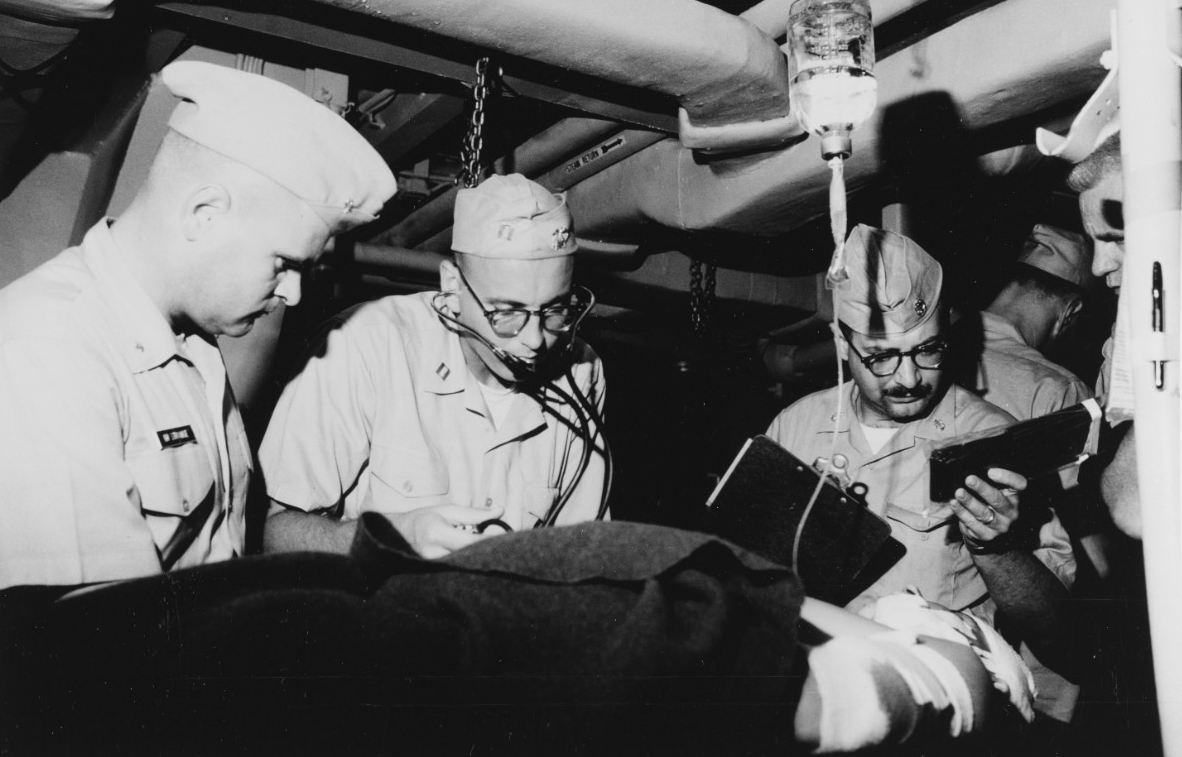

On June 16, 1965, the U.S. Navy scheduled the reactivation of USS Repose (AH-16), which would be the first hospital ship active during the Vietnam War. After the ship was reactivated and towed to various shipyards for repairs in the state of Washington, Repose was recommissioned on Oct. 16, 1965, at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, California, with Capt. Eugene H. Maher in command and Capt. Paul R. Engle as the senior medical officer. Repose departed San Francisco on Jan. 3, 1966, arriving at Pearl Harbor six days later for underway training. It then set course for Subic Bay in the Philippines, arriving on Feb. 3 to take on supplies and conduct repairs. Steaming on Valentine’s Day 1966 for Vietnam, Repose arrived two days later and commenced medical support off Chu Lai. Living up to its nickname, “Angel of the Orient,” Repose was permanently deployed to Southeast Asia until it departed Vietnam on March 14, 1970, when it was decommissioned and placed in reserve.

During its extended stay in Southeast Asian waters, the 741-bed floating hospital ship treated more than 9,000 battle casualties and admitted more than 24,000 for inpatient care. Repose earned nine battle stars for its Vietnam service.

The ship was no stranger to the combat zone. Commissioned toward the end of World War II in May 1945, Repose was deployed to Shanghai, China, where it operated as a base hospital until October 1946. Afterwards, it was placed in reserve until the Korean War broke out in June 1950. With a desperate need for hospital ships, Repose was transferred to San Francisco and ordered activated at the earliest possible date. It steamed with a civilian crew for Yokohama, Japan, on Sept. 2, 1950, and arrived two weeks later. There, a Navy crew embarked, and the next day it set course for Pusan, Korea, arriving on Sept. 20. Repose served off Pusan as a station hospital through Oct. 26, then departed for Yokohama with 189 patients. Returning to Korean waters on Nov. 13, Repose served at Inchon, Chinnampo, and Pusan before transporting 301 patients back to Yokohama. After undergoing availability repairs, Repose provided hospital services between Korean and Japanese ports throughout the rest of the year.

Following overhaul and installation of a helicopter platform, Repose returned to Inchon Harbor on June 24, 1952, where it began taking patients the same day. About a month later, Repose was joined by its sister ship USS Haven (AH-12) during increased Chinese participation and as the air war over Korea intensified. Following a period of patient transfers between Korea and Japan, Repose returned to the U.S. West Coast where it underwent repairs. After work was completed and for the remainder of the Korean War, the ship took up station at Inchon. Repose earned nine battle stars for its Korean service.

Today in Naval History

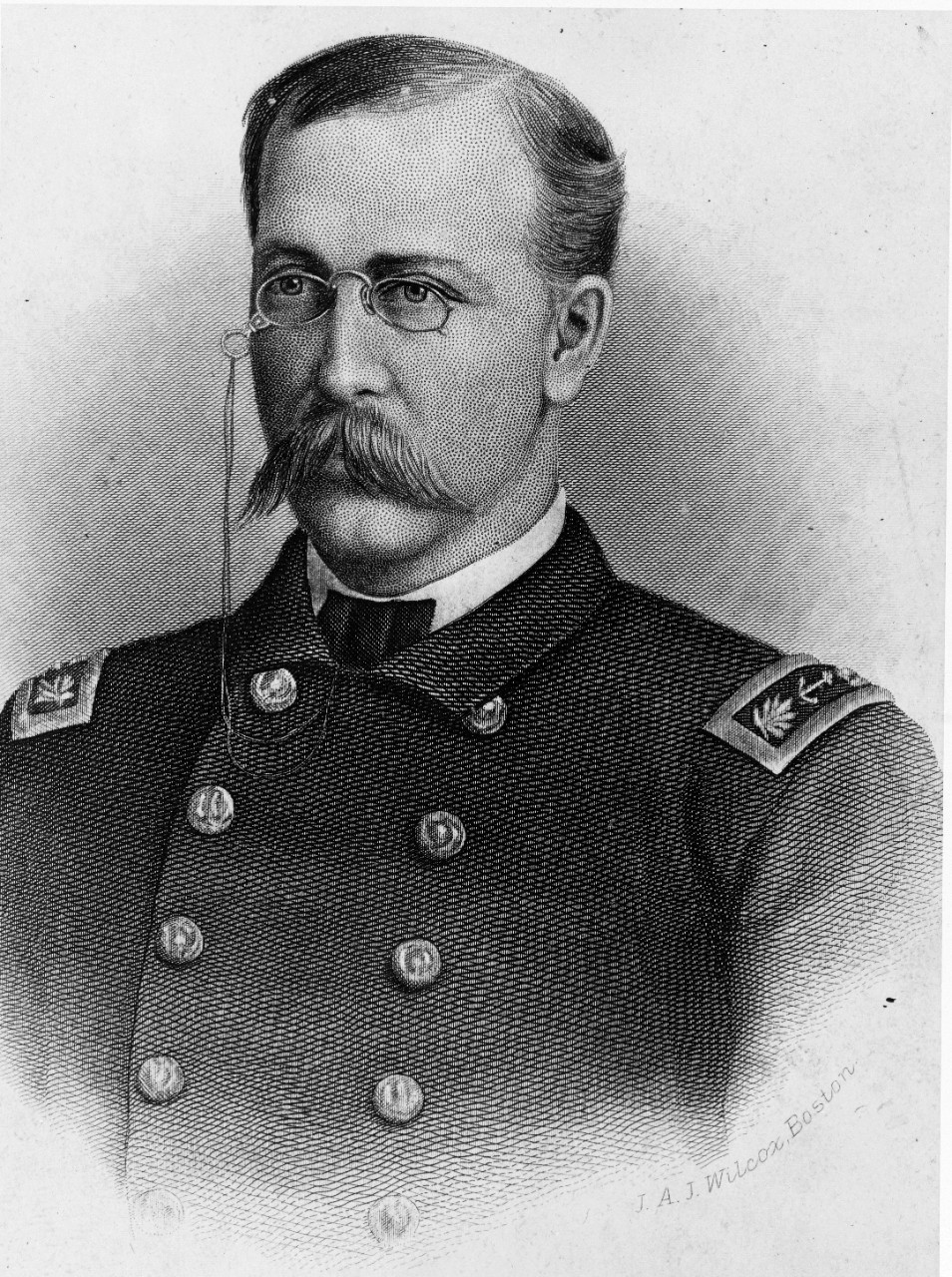

On June 13, 1881, bark-rigged, propeller-driven steamship Jeannette sank after it was crushed the previous day in an Arctic ice pack during an expedition to reach the North Pole through the Bering Strait. Commanded by Lt. Cmdr. George Washington DeLong, Jeanette was originally a gunboat in the Royal British Navy, but was purchased by New York Herald owner James Gordon Bennett for Arctic voyages. Bennett, an Arctic enthusiast, obtained U.S. Navy assistance in fitting out an expedition to the North Pole in March 1878 when Congress authorized the detailing of naval officers for the voyage. DeLong, a veteran explorer, accompanied Bennett to Europe to select a ship. Once it was purchased, DeLong sailed Jeanette from Havre, France, to San Francisco during the summer and fall of 1878.

At the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California, Jeanette was fitted with the latest scientific equipment and considerably strengthened for the harsh northern waters. Although the ship was privately owned, Jeanette set sail under the orders of the Navy. The crew consisted of 28 officers and Sailors and three civilians. Jeanette departed San Francisco on July 8, 1879, and pushed northward to Alaska’s Northern Sound. It sent its last communication to Washington before heading north from St. Lawrence Bay, Siberia, on Aug. 27. The ship sighted Russia’s Herald Island on Sept. 4, but soon afterward was caught in the ice pack. For the next 21 months, the sturdy Jeanette drifted northwest toward DeLong’s goal of the North Pole. DeLong described in his journal the important scientific records kept by the Arctic party: “A full meteorological record is kept, soundings are taken, astronomical observations made and positions computed, dip and declination of the needle observed and recorded. . . . Everything we can do is done as faithfully, as strictly, as mathematically as if we were at the Pole itself, or the lives of millions depended on our adherence to routine.” In May 1881, two islands were discovered and named Jeannette and Henrietta. On the night of June 12, the pressure of the ice finally began to crush Jeannette. DeLong and his crew unloaded provisions and equipment onto the ice pack, and the ship was lost the following morning.

With little hope of a rescue effort, the expedition now faced a long trek to the Siberian coast. Nevertheless, they started off for the Lena Delta, hauling their boats and supplies. After reaching several small islands off Siberia and getting some food and rest, they launched their boats in hope of reaching the mainland. However, after a violent storm, one of the boats capsized, while the other two, commanded by DeLong and Chief Engineer George W. Melville, survived the storm but landed at widely separated points on the delta. One party, headed by DeLong, began the long trek inland over the half-frozen delta in hope of finding native settlements. Tragically, one by one the men died from starvation and exposure. Finally, DeLong sent the two strongest of the group ahead for help. Although the two sent ahead eventually found a settlement, DeLong and his companions died in the harsh environment.

In the meantime, the courageous Melville and his party found a native village on the other side of the delta and were ultimately rescued. After receiving help, Melville then began the journey to Belun, a Russian outpost, where he found the two survivors of DeLong’s group and persuaded a group of natives to go with him in search of his commander. He succeeded in finding their landing place and recovered Jeannette’s log and other important records, but returned to Belun on Nov. 27 without locating DeLong. Keeping only two of his party, Melville then turned northward once more, and finally found the bodies of DeLong and his companions on March 23, 1882. He then built a large marker over the grave of his shipmates.

Before leaving Siberia, Melville made a final attempt to find the remains of Jeannette’s third boat, even though the chance of survivors was slim. He returned disappointed to Irkutsk, the capital of Siberia, on July 5, 1882, almost three years since his departure from San Francisco in Jeannette. The results of the heartbreaking Jeanette Expedition, both meteorological and geographic, were important at the time, and Melville was awarded with the Congressional Gold Jeannette Medal for his courage and tenacity. DeLong and his shipmates were later disinterred from their Artic graves and transported across Russia, Europe, and the Atlantic Ocean before being buried in February 1885 at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York. In addition, a monument, the Jeanette Expedition Memorial, is located in the cemetery of the U.S. Naval Academy. It carries the names of DeLong and the other shipmates who did not survive the expedition. For more on polar exploration, visit NHHC’s website.