Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On March 21, 1917, Loretta Perfectus Walsh was sworn in as a chief yeoman, becoming the first female chief petty officer in the U.S. Navy. Four days earlier, Walsh had been the first woman to enlist in the Navy, having the distinction of being the first woman to serve in any of the U.S. armed forces other than a nursing assignment. Before Walsh enlisted, women served primarily in the medical field, but were civilian employees with few benefits. During World War I, more than 11,000 Yeoman (F) personnel—popularly referred to as Yeomanettes—served in the Navy. They primarily worked in clerical positions, received the same benefits and responsibilities as men (including identical pay of $28.75 per month), and were treated as veterans after the war. When the “Great War” ended, Walsh and all Yeoman (F) personnel were released from active duty. When Walsh joined the Naval Reserve for a four-year enlistment, she continued on inactive reserve status, receiving a modest retainer pay, until the end of her enlistment on March 17, 1921.

In the spring of 1917, the United States began preparing for the inevitable—war in Europe. However, men had not been enlisting in sufficient numbers. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels determined that women could be enrolled in the U.S. Naval Reserve Force as part of the Naval Act of 1916 and issued an order authorizing their enlistment. In an attempt to prompt more men to enlist, Lt. Cmdr. Frederick R. Payne received permission to swear in Walsh as a chief petty officer in a public setting. Walsh donned a modified chief petty officer’s uniform, and the event was covered by Philadelphia newspapers. The ceremony was eventually picked up nationwide. Reporters were told of the necessity to enlist women because not enough men were enlisting. The ploy worked and shortly thereafter, before the declaration of war, the enlistment of men and women dramatically increased.

Born on April 22, 1896, in Olyphant, Pennsylvania, Walsh attended St. Patrick’s Parochial & High Schools in Olyphant and Scranton & Lackawanna Business College in Scranton, Pennsylvania. After graduating from business school, Walsh went to work as a clerk for the Navy League in Philadelphia. Walsh worked for Lt. Cmdr. Payne’s wife in the women’s section of the Navy League for Preparedness. After she enlisted and was assigned to the Philadelphia Naval Home, Walsh volunteered to work during the peak of the influenza epidemic in 1918. Walsh fell victim to influenza in the fall of 1918 and later contracted tuberculosis. She died on Aug. 16, 1925, at the age of 29 in Olyphant, due to complications of the latter disease. She is buried in St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Olyphant.

In 1928, the National Yeoman F (NYF) society of female Navy veterans of World War I was incorporated “for patriotic, historical, and educational purposes….” In 1934, the NYF began a campaign to have Walsh’s remains buried at Arlington National Cemetery and have a monument erected. In addition, an area would be set aside for the future graves of female veterans of World War I. However, their attempts ultimately failed. Instead, funds were raised by the NYF and other veterans’ organizations for a monument that was dedicated at Walsh’s grave site in 1937. Although the NYF no longer exists, the monument for the Navy women of World War I still stands today. In addition, on March 21, 2021, the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat, Constitution, named one of its 24-pound long guns “Perfectus” to honor the first female citizen-sailor during a ceremony at Charlestown Navy Yard, Massachusetts. For more on women in the U.S. Navy, visit NHHC’s website.

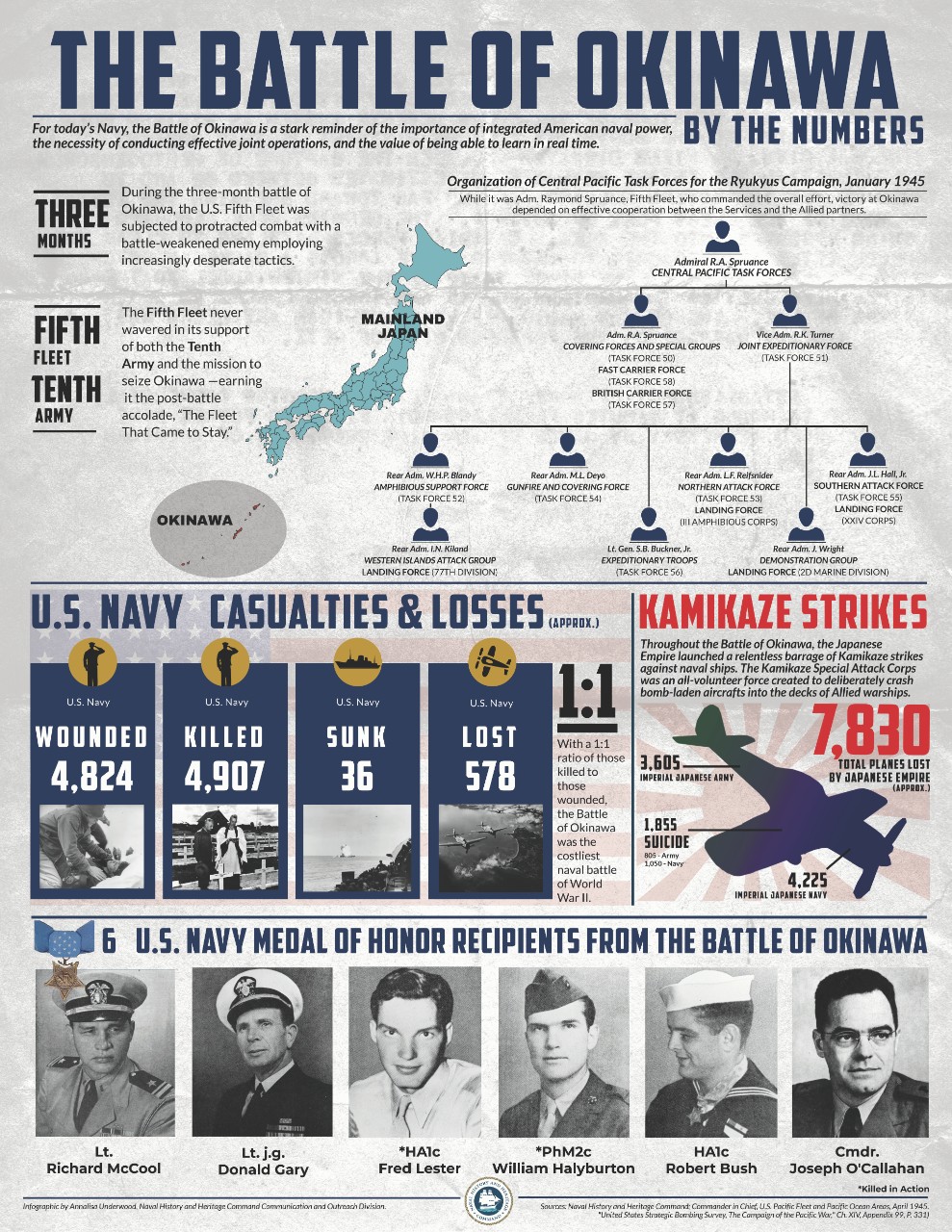

Battle of Okinawa

On April 1, 1945, under heavy naval gunfire and air support, U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps troops began the invasion of Okinawa, the last major amphibious assault of World War II. Capture of the island was considered a vital precursor to a ground invasion of Imperial Japan. Leading up to the invasion, more than 1,600 ships and 350,000 naval personnel would assemble to form one of the largest amphibious assault forces of the war. However, before an invasion of Japan could be considered, American forces would have to endure one of the most brutal battles of the war. On March 19, a preview of what awaited came while Task Force 58 conducted bombardment strikes on mainland Japan in an effort to blockade their supply lines for the invasion of Okinawa. During the strikes against Honshū and Kobe Harbor, aircraft carrier USS Franklin (CV-13) was hit by two bombs from a Japanese dive bomber. The crew ultimately saved the ship, but more than 800 of the crew were killed.

Although the Japanese military was greatly diminished at this point, U.S. planners expected that the ferocity of their resistance would continue to increase as American forces got closer to Japan. With action now mainly concentrated around the Central Philippines and the Ryukus, the Japanese were able to bring their land-based aircraft from Taiwan and Kyushu to the fight. However, these would not be used to conduct a conventional air campaign. Instead, the Japanese intended to use their land-based aircraft as human-guided missiles against U.S. forces. Such tactics, known as kamikaze, had been used sporadically at Leyte Gulf, Luzon, Lingayen, and Iwo Jima, but not on the particularly large scale that was expected. With Fifth Fleet so close to mainland Japan, Navy planners feared that as many as 3,000–4,000 enemy planes could be expected. Unfortunately, their estimates were correct, with the prolonged land battle enabling the Japanese to launch numerous air attacks that were more successful than anticipated. Adm. Raymond Spruance got an early taste of what was to come when a diving kamikaze barely missed his flagship USS Indianapolis (CA-35) while still severely damaging the ship with a bomb as it splashed into the sea. This forced Indianapolis back to San Francisco for repairs.

Despite the immense threat from the skies, the initial stages of the Battle of Okinawa went as planned. Minesweeping, pre-invasion bombardments, and tactical strikes from aircraft carriers paved the way for an uncontested amphibious landing of Lt. Gen. Simon Buckner’s Tenth Army that was made up of U.S. Army Soldiers from the 96th and 7th Divisions, as well as Marines from the 1st and 6th Divisions. The force landed on the western side of the island close to two airstrips. Unbelievably, the airstrips were taken uncontested as well. Immediately afterward, the ground force split. Marines moved northeast to secure the northern part of the island, the Army moved south toward Shuri. By mid-April, the Marines had secured their less-defended portion of the island, but the Army faced a more formidable Japanese defense, which led to a slower, more methodical advance. Later, the Marines joined the Army to slug it out with the Japanese, but suffered high casualties against the well-defended Shuri Line. The fierce fighting and the appalling numbers of casualties taken by U.S. forces continued into June, with the total number reaching 49,151, of which 12,520 were killed or missing. The Navy lost 32 ships and craft, mostly by kamikaze attacks, and 368 ships and craft were damaged. Additionally, 763 aircraft were lost.

The prolonged land battle had consequences at sea. As progress occurred slower than anticipated and with ground forces heavily dependent on Fifth Fleet, Spruance’s ships had no choice but to remain in the area to provide support, and presented inviting targets for kamikaze attacks. By the time Okinawa was declared secure on June 22, the toll on the Navy was the costliest of the war. It is estimated that nearly one out of seven Navy deaths during the entire war occurred during the bloody months off Okinawa.

With Iwo Jima and Okinawa secure, the American military had considerable latitude as to how it would conduct the war going forward, but the human cost of those bloody battles raised serious questions among the American public and military leaders as to the practicality of invading Japan. As President Franklin Roosevelt had died shortly after the beginning of the Okinawa campaign, President Harry S. Truman would have to make the decision how much more bloodshed the nation was willing to endure to secure Japan’s unconditional surrender. With the lessons learned from the Okinawa battle fresh in his mind, Truman would make the fateful decision to drop two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing the war to a close. The Battle of Okinawa became not only the final major engagement of the war, but a grim testament to what the future might have held for U.S. and Allied forces had they continued onward to the Japanese mainland.

The Four Chaplains

On March 29, 1944, USS Ericsson (DD-440) and USS Kearny (DD-432), along with three submarine chasers, sank German submarine U-223, which had sunk five Allied merchant vessels, including U.S. Army transport ship Dorchester of “the four chaplains” fame.

Shortly after midnight, on Feb. 3, 1943, Dorchester was one of three ships in a convoy, moving across the Atlantic from Newfoundland to an American base in Greenland. Dorchester, a converted luxury liner, was filled to capacity with 902 service members, merchant seamen, and civilian workers. About 150 miles from their destination, U-223 spotted the convoy. Soon thereafter, the German commander gave the order to fire torpedoes on Dorchester. The spread of torpedoes was decisive, striking the ship below the waterline. The initial blast killed scores of men and wounded many more. Others, stunned by the explosion and in complete darkness, began to panic. Chaos quickly ensued as men were screaming, and others were crying or franticly trying to get lifeboats off the ship.

Through the pandemonium, four men spread out among the crew, calming the frightened, tending to the wounded, and guiding the disoriented towards safety. They were four U.S. Army chaplains: Lt. George Fox, a Methodist; Lt. Alexander Goode, a Jewish rabbi; Lt. John Washington, a Roman Catholic priest; and Lt. Clark Poling, a Dutch Reformed minister. Quickly and quietly they brought calm to the situation. As passengers and crew began to make their way to the deck, many were still in their underwear as they had been asleep at the time of the attack. When they were topside, they were confronted by the harsh cold arctic winds.

Petty Officer John J. Mahoney, shocked by the extreme cold, started to head back down into the ship. “Where are you going?” a calm voice asked. “To get my gloves,” Mahoney replied. “Here, take these,” said Rabbi Goode as he handed a pair of gloves to the young man. “I can't take those gloves,” Mahoney replied. “Never mind,” the rabbi responded. “I have two pairs.” It was then that Mahoney realized that the chaplain never intended to leave the ship.

While topside, the four chaplains began distributing life jackets. When there were no more life jackets available, the chaplains simultaneously took theirs off and handed them to the next men in line. As the ship went down, survivors witnessed the four chaplains, arms linked and braced against the slanting deck. Their voices could be heard praying and singing hymns.

Of the 902 aboard Dorchester, only 230 survived. Although Distinguished Service Crosses and Purple Hearts were later awarded to the four chaplains posthumously, Congress attempted to award them Medals of Honor, but was blocked by the stringent requirements that required heroism performed under fire. Consequently, a posthumous special medal for heroism, The Four Chaplains’ Medal, was authorized by Congress and awarded by the President on Jan. 18, 1961.

Oldest Warfare Insignia Device

Recently, NHHC added a new page on its website on the Navy’s oldest warfare device.

In the summer of 1923, while serving as the commander of Submarine Division Three, then-Capt. Ernest J. King proposed that the Navy create a warfare insignia device for qualified submariners. The insignia came to be known as “dolphins” or “fish.” The hard-earned badge distinguishes and identifies the members of the submarine community and has since become a source of pride for the “silent service.” Not only did King propose the idea for the submarine warfare device, he also submitted the initial design. His drawing, which he submitted to the Bureau of Navigation for consideration, included a shield mounted on the beam ends of a submarine, with dolphins forward and aft of the conning tower. The bureau considered a shark and shield motif as well, but ultimately hired a Philadelphia jeweler to create the design. The final design of the device was approved for wear on March 24, 1924. It displayed a bow view of a surfaced O-class submarine with two dolphins resting their heads on the submarine’s bow planes. The dolphins depicted on the insignia were actually dolphinfish, or mahi-mahi, not the marine mammal. From 1924–1947, qualified enlisted personnel wore an embroidered cloth version of this design on their right sleeve, midway between the wrist and elbow. Officers wore a gold-plated metal pin on their left breast above their ribbons and medals. In 1947, new regulations dictated that enlisted personnel wear the embroidered insignia on their left breast—in the same position as officers. When the Navy began allowing officers to embroider gold insignia on their uniforms in 1950, enlisted personnel were allowed to wear a silver-plated metal version of the pin.

Beginning in 1943, the Navy authorized a new design for medical officers in which the submarine motif was replaced by two fish flanking a silver acorn over a gold oak leaf. In 1950, submarine engineering officers were granted their own insignia, in which the submarine motif was replaced by a gold disc inlaid with the letter “E.” The letter was replaced two years later with a ship’s screw. Not to be forgotten, submarine supply officers received their own version of the insignia in 1964 that displayed three oak leaves bordered by acorns. Submarine personnel also designed their own unofficial insignias specific to their submarine community. Deep-water submarines as well as nuclear submarine personnel developed their own insignia. Submariners with an affinity for diesel boats also created enlisted and officer metal badges emblazoned with the letters DBF (diesel boats forever) on the bottom border.

The device, however, is more than just another addition to the uniform. The process of qualifying for “dolphins” on board a submarine is not optional—it’s a requirement for submarine service so that everyone aboard can take immediate action when an emergency occurs. To qualify, Sailors must learn everything about a submarine’s systems, operation, and construction. They learn where the damage control gear equipment is located in every compartment, how to plug and patch leaks, extinguish fires, and rig compartments for casualty situations. The qualification process for officers and enlisted is similar and typically takes a year to complete. Submarine officers and enlisted personnel must demonstrate extensive knowledge of all submarine systems, operations, and compartments as well as damage control, casualty procedures, and watch standing. Submariners under instruction complete a qualification card that lists all the submarine systems, compartments, and equipment. Personnel obtain signatures upon receiving proper training and showing understanding of the boat’s equipment. Upon gaining all their required signatures, they must then pass an oral board. Upon transferring to a new class of submarine, Sailors must requalify on the new submarine.

In 2010, the Navy lifted the ban barring women from serving on submarines. In June 2012, Lt. Britta Christianson, Gold Crew supply officer for the guided-missile submarine Ohio (SSGN-726), earned her submarine supply corps insignia, making her the first female supply corps officer to qualify in submarines. In December 2012, the first three female unrestricted line officers, Lt. (j.g.) Marquette Leveque, Lt. (j.g.) Amber Cowan, and Lt. (j.g.) Jennifer Noonan, qualified in submarines and were awarded their “dolphins.” In 2016, Chief Culinary Specialist Dominique Saavedra became the first female enlisted Sailor to earn her silver warfare insignia. For more on the submarine force, visit NHHC’s website.