Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On Nov. 15, 1994, Cmdr. Donnie L. Cochran was selected to be the first African American commanding officer of the U.S. Navy’s Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels. He served as commander for 18 months during the 1995 and 1996 seasons. Earlier in his career (1986–88), Cochran was the first African American Blue Angels pilot. Blue Angels pilots are usually limited to two seasons. However, in 1987, they transitioned from the A-4 Skyhawk to the F/A-18 Hornet, giving Cochran an extra year on the team. During his first two years, Cochran flew in the No. 3 jet position and, in his third year, flew the No. 4 position. As commanding officer, he flew in the No. 1 jet position.

To qualify for the Blue Angels, pilots must have a vast amount of tactical jet experience. Cochran previously flew the RF-8G Crusader on his first deployment aboard USS Nimitz (CVN-68), followed by the F-14 Tomcat on two deployments aboard USS Enterprise (CVN-65). In 1984, he applied to the Blue Angels, but unfortunately wasn’t selected. The following year, Cochran decided to try again, and that time was successful. After serving as a pilot for the Blue Angels, he moved on to other assignments in the Navy, including as commander of Fighter Squadron 111 (VF-111), which deployed with USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) and earned the Battle E and Safety S awards. In 1994, he was selected over five other candidates for the coveted Blue Angels commanding officer position and history was made. During Cochran’s illustrious career as a naval aviator, he made 888 carrier landings, took part in more than 300 air shows and practice air shows, and in 350 maneuvers in a fighter jet inverted at 380 knots.

Born on July 6, 1954, Cochran grew up on a farm near Pelham, Georgia, where his chores included harvesting okra alongside his eight brothers and three sisters. The family farm was located along a flight path taken by military aircraft, and Cochran has fondly recalled the excitement provided by the high-speed, low-flying airplanes as inspiration for his career as a pilot. In 1976, Cochran graduated from Savannah State University, earning a degree in civil engineering technology and a commission in the U.S. Navy. Two years later, he earned his wings of gold and was assigned to Light Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron 63 (VFP-63), flying the Crusader at Naval Air Station Miramar, California. It was at Miramar that he saw his first Blue Angels show and his fascination with the historic flight demonstration team began.

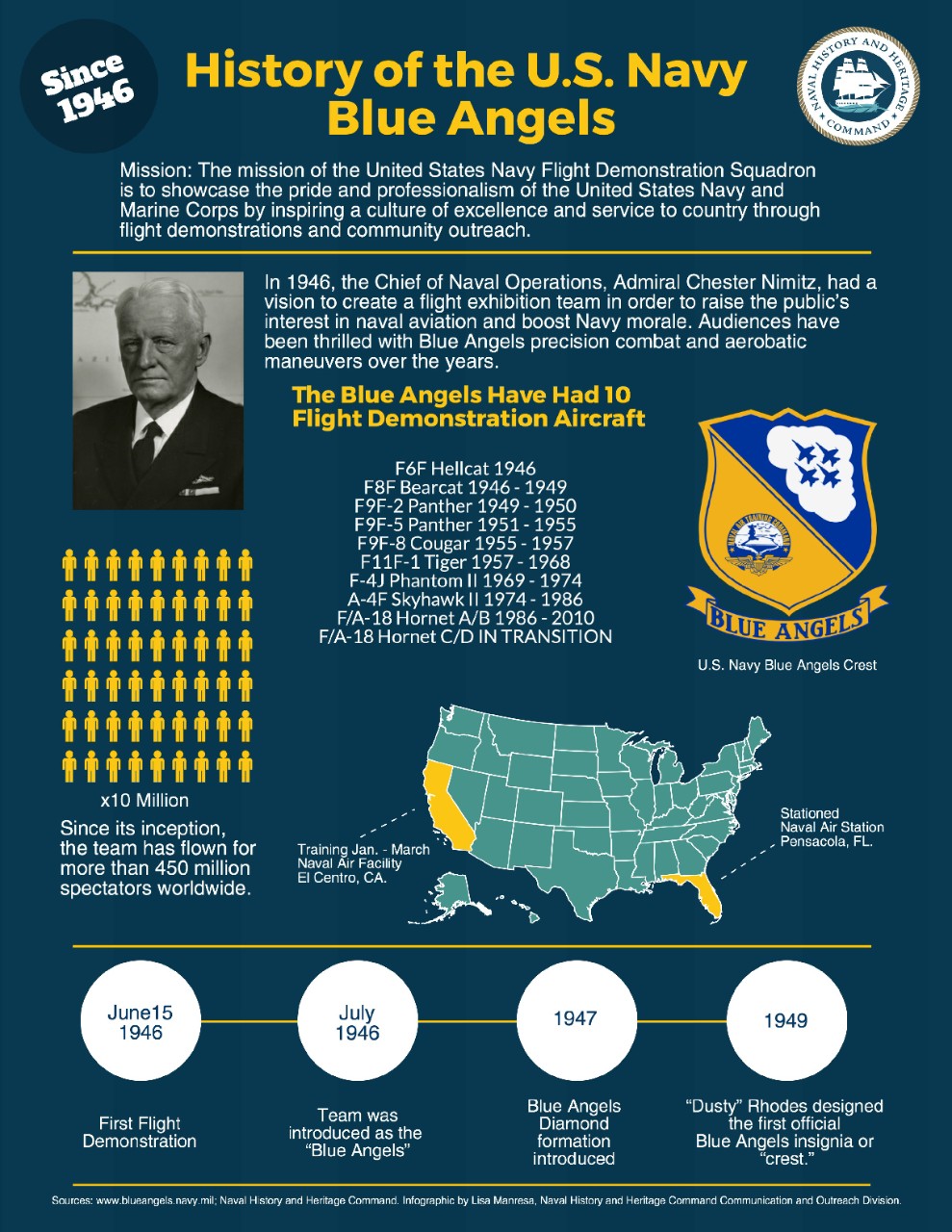

Following World War II, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Chester W. Nimitz ordered the formation of the team with the goal of increasing public awareness and appreciation of naval aviation. In July 1946, the team was first introduced as the Blue Angels at an air show in Omaha, Nebraska. In their first year, the Blue Angels simulated World War II battles with an SNJ-5 Texan that had been painted and configured to resemble a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero. The Blue Angels’ famous diamond formation was introduced a year later, which led to other new maneuvers such as the diamond loop and the diamond barrel roll. These maneuvers are still performed today by the team. Currently, the Blue Angels are stationed at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida, during air show season, and train at Naval Air Facility El Centro, California, during the off-season. The Blue Angels are viewed by an estimated 11 million spectators each year during air shows, and they visit more than 50,000 people per year during school and hospital visits, and other community events.

First Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier Commissioned

The world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise (CVN-65), was commissioned on Nov. 25, 1961, in Newport News, Virginia. After commissioning, Enterprise—constructed from 60,923 tons of steel, 1,507 tons of aluminum, and 230 miles of piping and tubing—began a lengthy series of tests and training exercises designed to determine the aircraft carrier’s full capabilities. In early tests, its eight nuclear reactors generated such horsepower capacity that Enterprise literally ran circles around accompanying petroleum-powered escort ships. After qualifications, Enterprise set course on its first mission as part of the Project Mercury recovery force. Three carriers, including the “Big E,” patrolled the most likely areas for reentry and impact of the capsule, but unforeseen delays postponed the second attempt to send a man into space. Enterprise returned to its homeport of Norfolk, Virginia. The following year, Enterprise had its second chance in the historic early days of America’s space program when Mercury-Atlas 6 launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, with Marine Lt. Col. John Glenn as the astronaut. After becoming the first American to orbit the Earth in space, Glenn splashed down in the Atlantic about 800 miles southeast of Bermuda. Enterprise tracked and measured the entire historic flight, which was NASA’s main objective for the orbit.

In the fall of 1962, Enterprise took part in its first international crisis when the Soviet Union began secretly deploying medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles on Cuba. During what was dubbed the Cuban Missile Crisis, Enterprise took part in the successful blockade of the Communist country that ultimately, along with intense diplomatic efforts, prevented the Soviet Union from further escalation. This could have resulted in a Soviet nuclear strike on American soil. Enterprise, with its immense power-projection capabilities, deployed 120 sorties daily. The efforts of the Enterprise crew and its embarked aircraft proved critical to the successful resolution of the crisis.

Beginning in May through October 1964, the capabilities of the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier continued to impress the leadership of the U.S. Navy. Along with USS Bainbridge (DLGN-25) and USS Long Beach (CGN-9), Enterprise participated in Operation Sea Orbit, an all-nuclear task force that circumnavigated the globe without refueling. Following the groundbreaking cruise, Enterprise was redesignated CVAN-65 (attack aircraft carrier) and deployed in November 1965 for service in the Vietnam War. Enterprise was the first nuclear-powered ship to engage in combat, utilizing its aircraft against North Vietnam. During the deployment, three days before Christmas 1965, 110 aircraft from Enterprise, Kitty Hawk (CVA-63), and Ticonderoga (CVA-14) launched a massive coordinated strike against the Uong Bi Thermal Power Plant, 15 miles northeast of Haiphong and a source of national pride for the North Vietnamese. The air crews essentially destroyed the plant, temporarily disrupting approximately two-thirds of the power to Hanoi and Haiphong. It was the first authorized industrial strike by naval aircraft in North Vietnam. Enterprise remained off Vietnam, aside from a short trip to Taiwan until June 1966. In February 1967, Enterprise returned to Vietnam and resumed operations against North Vietnam. Tragedy struck on Jan. 14, 1969, when an explosion involving an F-4 Phantom killed 27 Sailors and injured another 314. Although the fires from the explosion were brought under control quickly, the ship was sent to Pearl Harbor for extensive repairs. After repairs were completed, Enterprise continued to serve off and on in Vietnamese waters until 1973. In 1975, the aircraft carrier returned to Vietnam to participate in Operation Frequent Wind, the evacuation of Saigon. The following year, Enterprise was redesignated back to CVN-65.

Deployed mainly in the Pacific, Indian, and Mediterranean during the late 1970s and 1980s, Enterprise was pivotal in the April 1986 Operation El Dorado Canyon—the bombing of terrorist-related activities in Libya. The strike was in retaliation for the direct role Col. Muammar Qaddafi’s regime had in the bombing of a nightclub in the Federal Republic of Germany. Two years later, Enterprise provided support for Operation Earnest Will, the protection of Kuwaiti-owned tankers from Iranian attacks during the Iran-Iraq War. Enterprise was also involved in Operation Praying Mantis, the response to the Iranian mine strike on USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58).

In the early 1990s, Enterprise completed another around-the-world cruise before it returned to Newport News for a lengthy overhaul. The carrier returned to sea duty in September 1994 and later enforced no-fly zones over Bosnia during Operation Joint Endeavor and over Iraq during Operation Southern Watch. In 1998, Enterprise also spearheaded Operation Desert Fox, the destruction of Iraqi military targets with more than 300 Tomahawk missiles.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Enterprise was returning home from the Persian Gulf when the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, DC, took place. Enterprise quickly returned to the waters off Southwest Asia and awaited orders. In October, in response to the 9-11 attacks, the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom with air attacks on al-Qaeda training camps and Taliban military installations in Afghanistan. Over the first three weeks of the operation, aircraft from Enterprise flew nearly 700 missions and dropped more than 800,000 pounds of ordnance. The ship returned to Norfolk afterward and underwent a scheduled dry docking. In September 2003, Enterprise deployed back to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom to relieve the carriers on station. The ship provided aerial support for the operation before returning back to Norfolk. Enterprise was again in the Persian Gulf in 2006 in support of both operations. For the remainder of its time in commission, Enterprise underwent further refurbishments and short deployments until deactived in 2012. The carrier was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on Feb. 3, 2017.

Over the course of its 51 years of service, Enterprise made 25 deployments (10 major operations) and 400,000 arrested landings were made on its flight deck. More than 100,000 veterans have served on the storied deck of the “Big E.”

Sculpin Lost, Crew Taken as POWs

On Nov. 16, 1943, USS Sculpin (SS-191) arrived in its designated area of operations from Pearl Harbor to intercept and attack Japanese ships departing to counter the upcoming U.S. invasion of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. Sculpin and two other submarines were to form a wolf pack to make coordinated attacks on the enemy. Capt. John P. Cromwell was on board Sculpin to coordinate the operation. Two days later, Sculpin made radar contact with a large, high-speed enemy convoy. The following morning, Sculpin surfaced to attack, but after detection, the enemy started to zigzag toward the submarine, making it difficult for the Americans to score a torpedo hit. The Japanese convoy then changed course. Sculpin dove and then resurfaced to attempt another attack, but a Japanese destroyer was waiting only 600 yards away. Sculpin crash-dived, surviving the first salvo of depth charges. A second wave of “ash cans” knocked out the boat’s depth gauge and caused other minimal damage. After evading the enemy destroyer in a rain squall, Sculpin attempted to come to periscope depth, but with the depth gauge stuck at 125 feet, the submarine was easily detected when it broached. Sculpin dove again. The enemy subsequently rained 18 depth charges on Sculpin, causing significant damage to include temporary loss of depth control. As a result, Sculpin dove beyond a safe depth and numerous leaks began to develop in the hull. So much water entered the submarine that it was forced to run at high speed to maintain depth. This made tracking easy for Japanese sonar. A further depth charge attack knocked out Sculpin’s sonar, leaving the submarine blind.

After coming to the realization that Sculpin was dead in the water, the submarine’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Fred Connaway, ordered his doomed boat to surface to give the crew a chance at survival. With its decks still awash, Sculpin’s Sailors manned the 3-inch deck gun, but they were no match for the enemy destroyer’s main battery. A shell hit the conning tower, killing the bridge watch team, including Connaway. Flying fragments also killed the gun crew. Cromwell, the ship’s senior surviving officer, ordered the submarine to be scuttled. Cromwell possessed vital information on the upcoming assault on the Gilbert Islands and other important future operations and feared he might reveal the plans if he was captured. The Japanese were infamous for their barbaric techniques in extracting information, which included torture. Cromwell refused to be captured or abandon the submarine. He went down with the boat, giving his life, to escape capture.

After the American submarine slipped below the waves, destroyer Yamagumo picked up 42 of Sculpin’s crew (one badly injured Sailor was mercilessly thrown back in the sea). After 10 days of questioning at the Japanese naval base at Truk, the prisoners of war were loaded on two aircraft carriers headed for Japanese prison camps. Escort carrier Chuyo carried half of the POWs. On Dec. 2, USS Sailfish (SS-192) torpedoed and sank Chuyo. The attack killed all but one of the American prisoners on board, who managed to grab hold of a ladder on the side of a passing Japanese destroyer and hauled himself on deck. The remainder of Sculpin’s survivors, who were on another aircraft carrier, made it safely to Japan and labored in copper mines for the duration of the war.

Two years after his death, Cromwell’s heroism in Sculpin’s final engagement was brought to light by the surviving crew, and he was subsequently awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. His wife, Margaret, received his Medal of Honor and placed it on her son, John. Cromwell was also awarded the Legion of Merit and the Purple Heart.

First U-Boat Sunk by U.S. Navy During World War I

On Nov. 17, 1917, six months after the United States had declared war on Germany, destroyers Fanning (DD-37) and Nicholson (DD-52) sank the German submarine U-58 off Milford Haven, Wales. At approximately 4:20 p.m., a sharp-eyed lookout on board Fanning spotted the enemy submarine’s periscope, which projected a mere foot above the water about 400 yards away. U-58 crossed the destroyer’s bow, and Fanning commenced chase, ringing down full speed and swinging the ship into position over the enemy submarine. After dropping a single depth charge that wrecked U-58’s motors, diving gear, and oil leads, the boat plunged to 200 feet before blowing ballast for a rushed ascent. Fanning spotted the submarine come to the surface with the conning tower exposed. Nicholson dropped another charge close to the submarine, scoring another hit. Nicholson then opened fire with its after gun. Fanning followed suit and scored several hits on the U-boat. Immediately thereafter, the submarine’s hatch flew open, and German sailors quickly clambered onto the deck with their hands in the air.

Fanning maneuvered alongside the foundering U-58, and the destroyer’s crew threw lines to the surviving German sailors. Thirty-five, including the commander, were taken as prisoners of war. While the U.S. crew kept the survivors under strict guard, they treated them with respect and dignity, giving them hot coffee and sandwiches. When the Germans disembarked at Queenstown, Ireland, which ultimately led to their captivity at a war prison camp in Fort McPherson, Georgia, they showed their appreciation to the American Sailors by cheering Fanning as they left the ship.

Fanning’s victory prompted many celebrations. Two days later, Royal Navy Adm. Lewis Bayly, commander-in-chief of the coast of Ireland, came on board and read a congratulatory cablegram praising the ship’s crew. Capt. Joel Pringle, chief of staff of the U.S. destroyer flotilla operating in European waters, also visited and read similar laudatory cables from CNO Adm. William S. Benson and Vice Adm. William S. Sims, commander of in-theater U.S. naval forces. Bayly even authorized Fanning’s crew to paint a coveted white star on the ship’s forward funnel to proclaim its victory over U-58.