Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

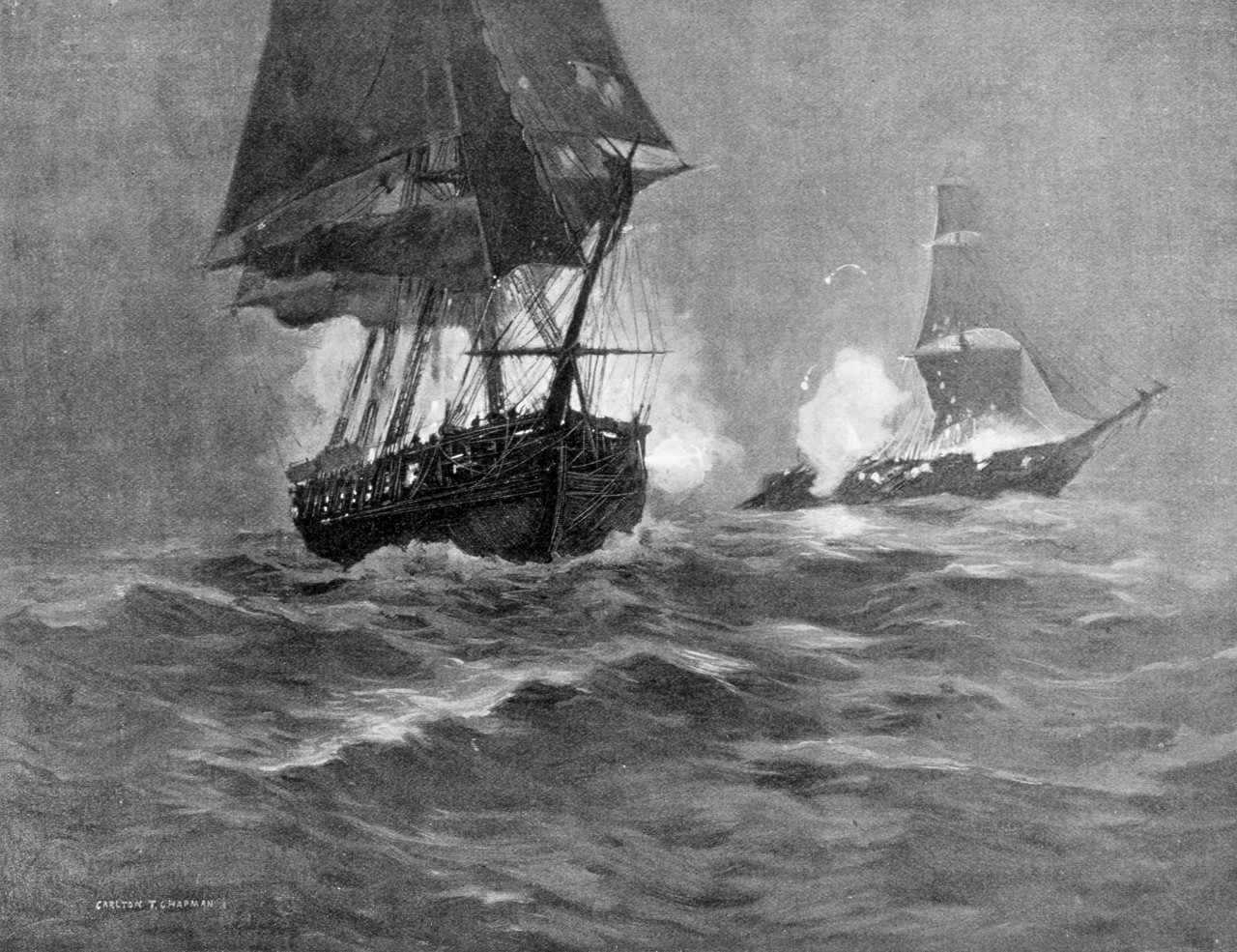

In the late afternoon of June 28, 1814, during the War of 1812, sloop-of-war Wasp, commanded by Master Commandant Johnston Blakeley, came upon HMS Reindeer, commanded by Commander William Manners, 225 miles west of Plymouth, England. Wasp was under orders to attack British shipping in the English Channel and had already captured seven enemy ships. Reindeer was ordered to engage Wasp. The battle lasted only 19 minutes, but during that brief span of time, both sides traded a barrage of broadsides before the ships came into direct contact. Several times, Reindeer’s crew tried to board Wasp, but the American crew repulsed them on each occasion. In the end, it was Wasp’s crew that boarded the British ship. After they boarded, the British commander continued to urge his crew to fight back until he was killed by a musket shot from Wasp’s rigging. Once onboard, the Americans swarmed the British crew and drove them below deck. The British captain’s clerk, who was one of the last remaining officers onboard Reindeer, eventually surrendered to the Americans. The crew of Wasp took the surviving sailors as prisoners, and after deciding the ship was too damaged to take as a prize, burned it. Wasp suffered 26 casualties with 11 killed in action. Reindeer had 25 killed and 42 wounded. Wasp suffered six hits to her hull, and some of her rigging was shot away, but she was still operational. After taking prisoners onboard, setting fire to Reindeer, and watching her explode, Wasp set course for L'Orient, France. While en route, the damaged Wasp managed to take two more prizes, 112-ton brig Regulator on Independence Day and 151-ton schooner Jenny two days later. Not long thereafter, she entered L'Orient for repairs, provisions, and care for her wounded.

Wasp remained in L'Orient until she put to sea again on Aug. 17, 1814. On her third day underway, she captured the brig Lettice, and the following day, took another enemy ship, Bon Accord. Early in the morning of Sept. 1, she spotted a convoy of 10 ships escorted by 74-gun ship-of-the-line Armada. Wasp made way toward the convoy and singled out brig Mary, which was quickly taken. The crew took her crew as prisoners and burned the ship. The American sloop-of-war then attempted to take another ship in the convoy, but Armada chased her off. That evening, Wasp’s crew spied another sail on the horizon and gave chase. By 9:30 p.m., she had 18-gun, 477-ton brig Avon within range and opened fire. The British returned fire for about a half an hour, after which her battery ceased fire. When Wasp did the same and called for the ship’s surrender, the British answered with another cannonade. Wasp once again opened fire on the ship. Some broadsides later, Avon's guns fell silent once more, and Wasp repeated the call for surrender. Avon, at this point, was a badly battered hulk and had no choice but to comply. However, just as Wasp began to lower the boat for the prize crew, the lookout sighted another enemy brig. Wasp's crew manned their battle stations immediately in hope of taking the newcomer as well. Just then, two more British ships appeared on the horizon and Wasp was forced to give up the destruction of Avon to save herself. The lead British ship hauled in close to Wasp's stern and fired a broadside into Wasp’s rigging, which damaged her sails and running rigging considerably. Then, the British ship stopped the engagement and rendezvoused with the other two ships following her and the sinking Avon. Wasp departed the area.

The American warship continued to wreak havoc on the British merchant marine. On Sept. 12, she encountered another enemy brig and scuttled her, and two days later, sank the brig Bacchus. On Sept. 21, eight-gun brig Atlanta came into contact with Wasp, and she, too, suffered the humiliation of capture. Deemed too valuable to destroy, Atlanta was taken as a prize and sent to Savannah, Georgia. From the time Wasp and Atlanta parted company, nothing more was heard from the gallant American ship. She was last seen by a Swedish merchantman bound from Rio de Janeiro to Falmouth, England, about three weeks after the capture of Atlanta and was said to be headed for the Caribbean. It is believed that Wasp sank in a storm with the loss of all hands.

Operation Husky: Invasion of Sicily

The Allied decision to invade Sicily, following the conceivable defeat of Axis forces in North Africa, was a result of the Casablanca Conference held Jan. 14–24, 1943, between President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and senior military personnel. Initially, the Americans and British were at odds on the strategic value of the operation, but the British were able to successfully argue that an amphibious assault on the Italian island would divert and disperse Axis forces, and a positive outcome would also significantly reduce enemy air assets in the western Mediterranean. Following the defeat of German and Italian forces in Tunisia, allocation of land forces began in May 1943. The plan, dubbed Operation Husky, was the dispersed landings of brigade- and division-sized formations in the southeast, south, and northwest areas of Sicily to capture key enemy airfields that would pose a threat to the beachheads and the invasion fleet. The landings would also lead to the capture of nearly all of Sicily’s main port cities and secure them for immediate logistical support and future staging operations. Overall command of the operation was Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was commander in chief of all Allied forces in North Africa. However, operational command of naval and landing forces was carried out by the British. The invasion fleet was divided into two task forces: the eastern naval task force was taken from the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, and the western naval task force was formed around the U.S. Navy’s Eighth Fleet. The landing forces for the operation followed a similar organization. Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s eastern task force was made up of British Commonwealth formations (British Eighth Army and a Canadian infantry division). Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s, western task force was made up of in-theater U.S. Army formations (U.S. Seventh Army). Air support was provided by the combined U.S.-British Mediterranean Air Command.

On the night of July 9–10, U.S. and British airborne landings took place with the mission to secure key bridges and traffic points. However, due to strong winds and faulty navigation, they were only marginally successful, but the airborne units managed to cause confusion among the predominantly Italian army formations they encountered. The initial amphibious landings began on July 10 on the south and southeast coasts of Sicily. Although severe weather caused some delays and misdirection, the Italians strategy called for massing formations in areas beyond the beaches, which allowed Allied forces to disembark and assemble without much opposition. Despite some early tactical successes, counterattacks by the few German units then present on Sicily were hampered by difficulties coordinating with the Italians. Therefore, Montgomery’s task force was soon able to advance toward objectives north of the landing areas and Patton’s forces pushed quickly toward the west.

By mid-month, the advance of Allied forces were somewhat slowed by German reinforcements that were rapidly deploying from mainland Italy. Hotly contested sectors included the areas around Mount Etna and the eastern Sicilian port of Catania. However, enemy forces were steadily squeezed into northeastern Sicily due to the sheer mass of the Allied onslaught. Palermo, Sicily’s capital, fell to Seventh Army on July 22. In August, following a series of delaying actions, the Germans decided to evacuate their remaining forces across the Strait of Messina to southern Italy, which was completed by mid-August.

The success of Operation Husky was a contributing factor to Italy’s surrender the following month, the removal of Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, and the country’s shift to the side of the Allies. After Italy surrendered, the Germans were forced to counter Allied operations in mainland Italy, invariably weakening their frontline forces elsewhere, particularly those fighting in the Soviet Union. For the Allies, the operation provided a secure staging area for future engagements.

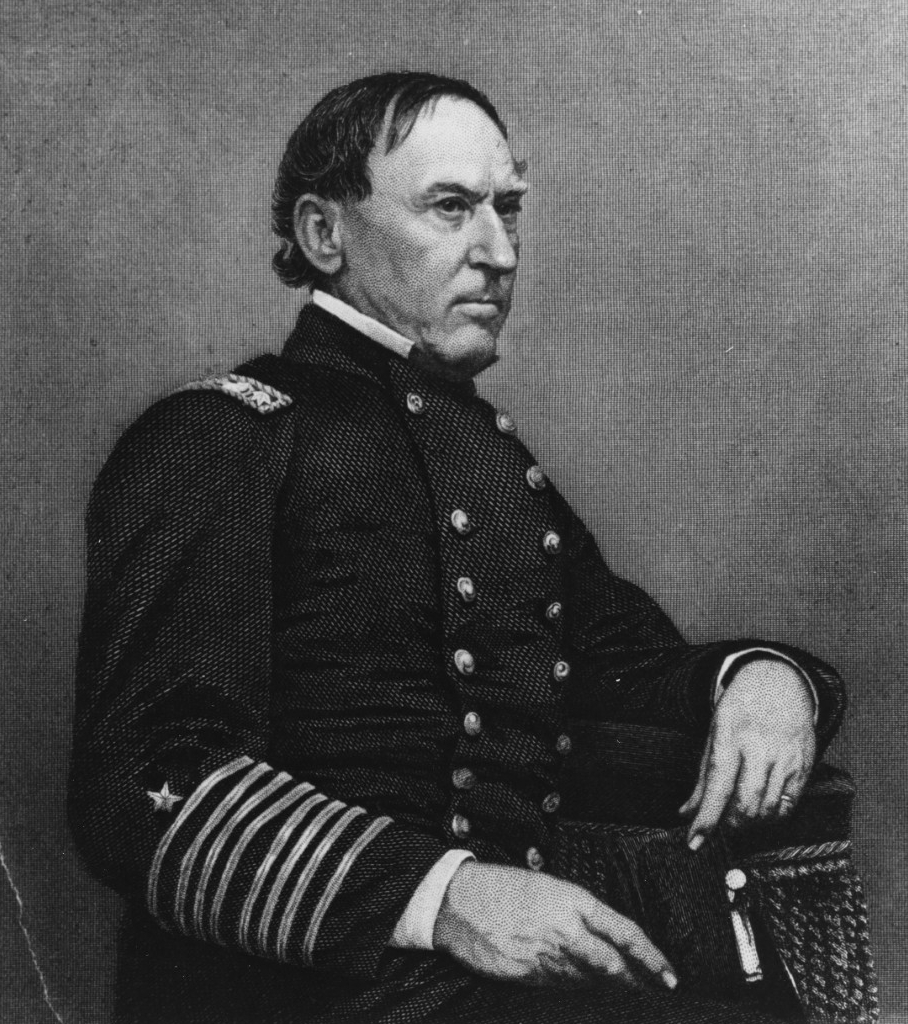

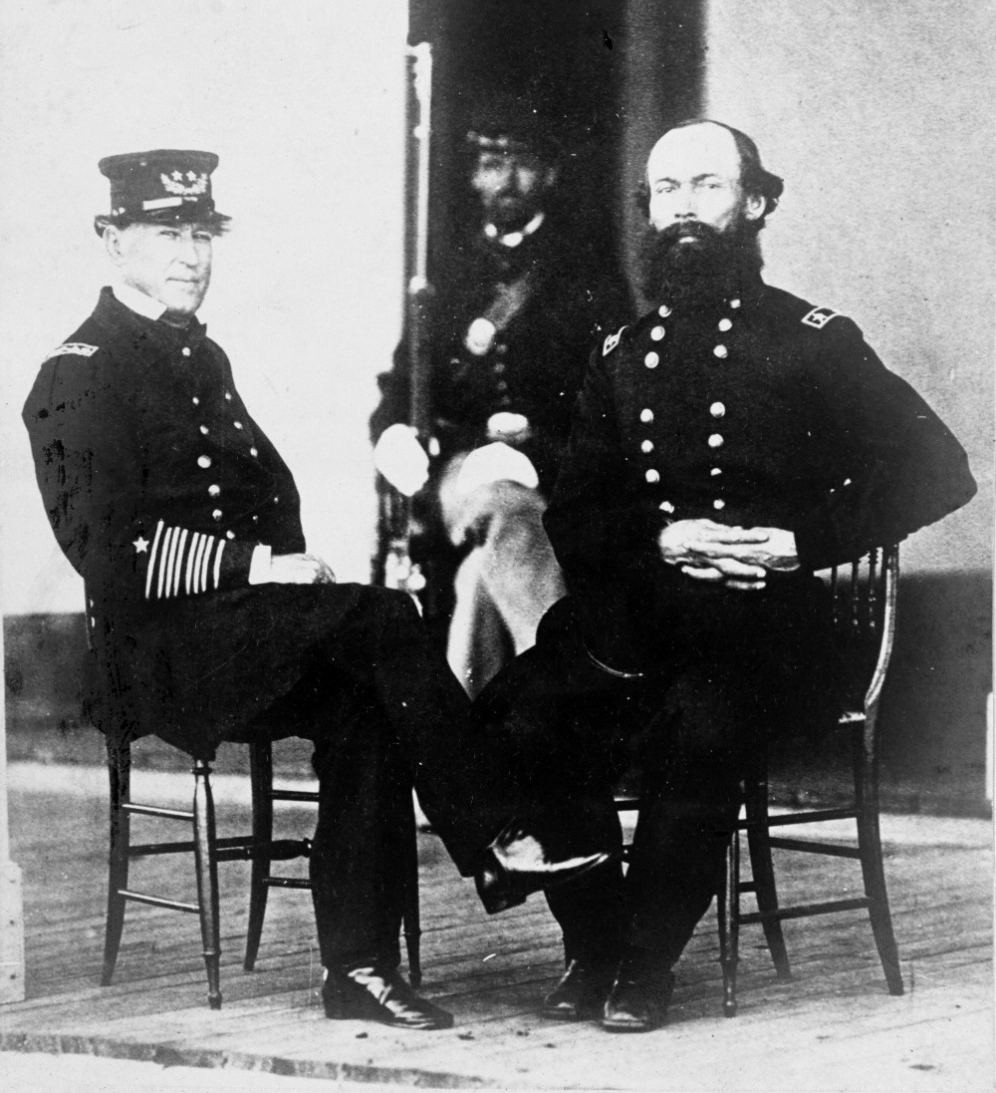

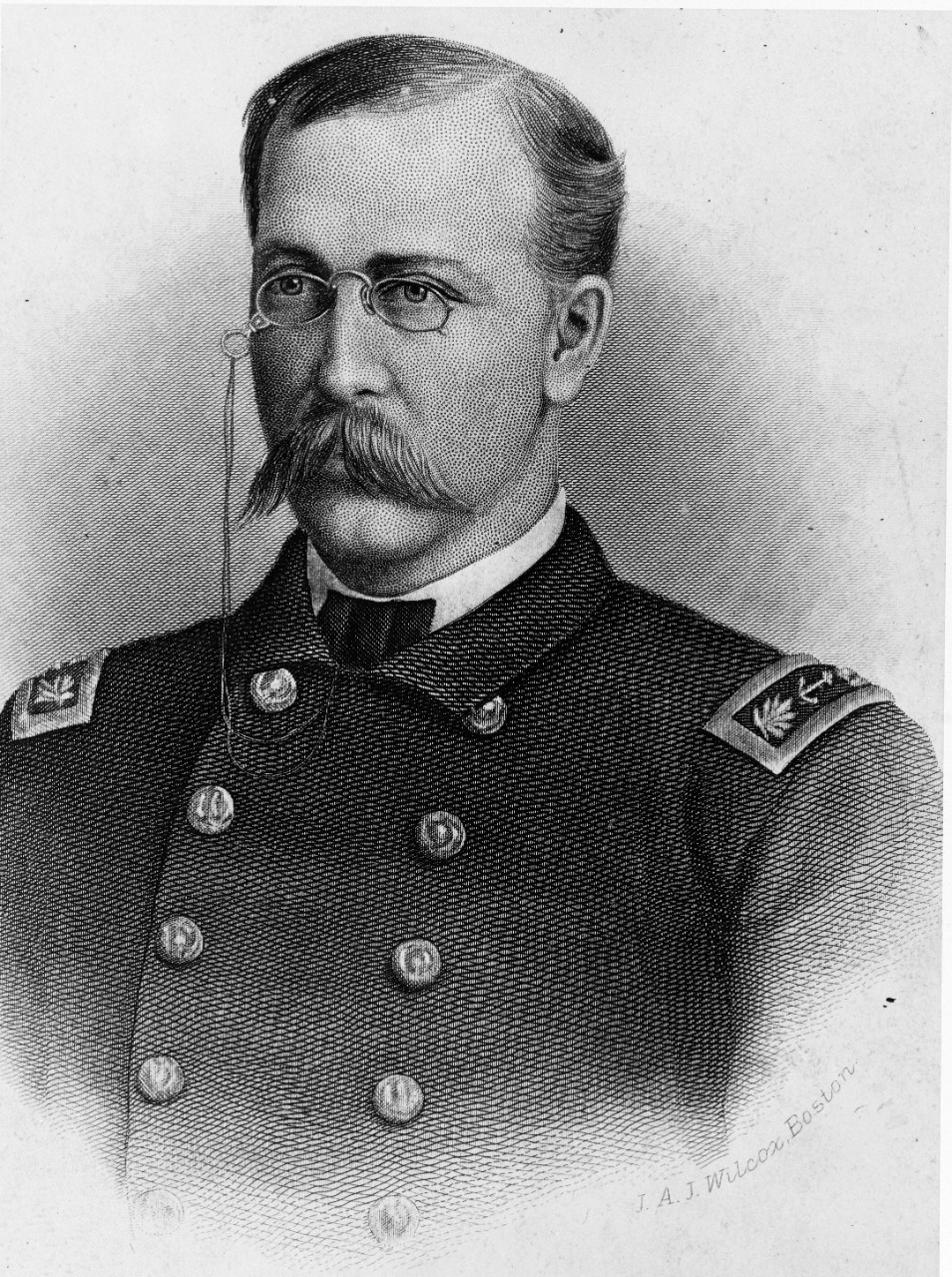

Adm. David G. Farragut’s Birthday

David Glasgow Farragut was born at Campbell’s Station near Knoxville, Tennessee, on July 5, 1801. Known for the quote “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” during the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864, he was appointed vice admiral by President Abraham Lincoln later that year and was commissioned an admiral—the first ever in the U.S. Navy—by a congressional act on July 25, 1866.

Farragut began his long naval career as just a young boy when he saw his first sea service off the coast of the United States in the frigate Essex in 1811. The following year, he was made prize master of Alexander Barclay, one of the ships captured by Essex. Farragut, then just 12 years old, took the prize safely to Valparaiso, Chile. Two years later, during the War of 1812, he took part in the battle between Essex and British ships Phoebe and Cherub off Valparaiso. After the war, in March 1815, he was ordered to ship-of-the-line Independence to cruise the Mediterranean, and remained with the U.S. Navy’s Mediterranean Squadron until 1820, after which he served with the “Mosquito Fleet” in the West Indies until 1823. After failing a preliminary examination for lieutenant in 1821, he tried again and passed, and was commissioned in August 1825. He served on the Brazil Station until late 1837, first as executive officer of Delaware, and later, as commanding officer of 10-gun schooner Boxer and sloop-of-war Decatur. While in command of sloop-of-war Erie at Vera Cruz, he witnessed the bombardment by French naval forces of the castle of San Juan de Uloa in 1838 and at that time called special attention to the importance of horizontal shell fire.

In April 1844, Farragut was named executive officer of receiving ship Pennsylvania and remained at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, until the Mexican-American War broke out. In March 1847, he was given command of sloop-of-war Saratoga, and during his time in command of the ship, saw service during the blockade of Tuxpan. From 1848–1854, he served in a variety of positions, during which time he worked on a book on ordnance regulations. In 1854, he was sent to the U.S. West Coast to establish the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, California, where he served as commandant until 1859.

When the Civil War began, Farragut was called upon to choose between his native state and the federal government, and upon declaring his allegiance to the Union, was given command of the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron in January 1862. Ordered to “proceed up the Mississippi River and reduce the defenses which guard the approaches to New Orleans ... and take possession of it under the guns of (his) squadron,” his passage of Forts Jackson and St. Philip (the defenses of New Orleans) in his fleet of wooden ships in April 1862 was a great achievement in naval warfare at a time when superiority of land fortifications over ships was asserted everywhere. His most stunning victory was the Battle of Mobile Bay, when he forced the passage of Forts Morgan and Gaines at the entrance to Mobile Bay and captured Confederate ram Tennessee and gunboat Selma.

In 1867, while in command of the European Squadron, he spearheaded an extended goodwill tour in his flagship Franklin. Upon his return to New York the next year, Farragut’s health began to fail. He performed his last official duty when he took charge of the naval ceremonies to honor American financier and philanthropist George Peabody, whose body had been brought to the United States on British ship Monarch. Farragut died the following year while on a visit to Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Farragut was married twice during his lifetime, first in 1823 to Susan C. Merchant, who died on Dec. 17, 1840. He married Virginia Loyall in December 1843 and they had a son, Loyall, who graduated from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York. Five U.S. Navy ships have been named in his honor.

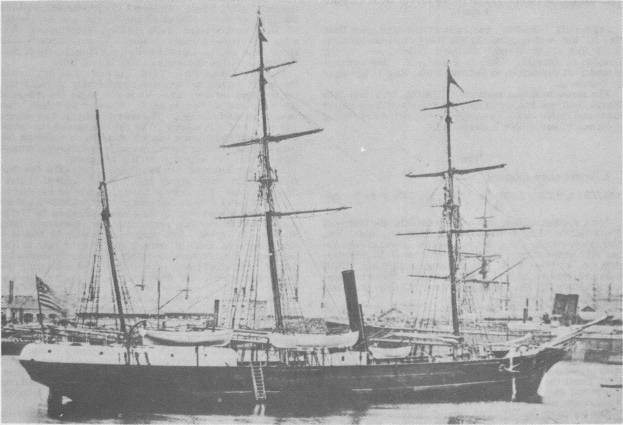

Jeanette Departed San Francisco for the Arctic

On July 8, 1879, bark-rigged wooden steamship Jeannette departed San Francisco to explore the Arctic. Prior to departing the northern California bay, Jeanette was fitted with the latest equipment and was considerably strengthened for northern service. Although she was privately owned by Arctic enthusiast James Gordon Bennett, Jeanette sailed under the orders of the Navy and was subject to naval laws and discipline. The crew consisted of 28 naval personnel and three civilians. The ship contained the latest in scientific equipment and, in addition to reaching the North Pole through Bering Strait, scientific observation ranked high among the expedition's list of goals. After departing, Jeanette pushed northward to Alaska's Norton Sound and sent her last communication to Washington before heading north from St. Lawrence Bay, Siberia, on Aug. 27. The ship sighted Herald Island on Sept. 4 and soon afterward was caught in the ice pack. For the next 21 months, the sturdy Jeannette drifted to the northwest, ever closer to the goal of the ship’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. George W. DeLong—the North Pole itself. He described in his journal the important scientific records kept by the party. “A full meteorological record is kept, soundings are taken, astronomical observations made and positions computed, dip and declination of the needle observed and recorded ... everything we can do is done as faithfully, as strictly, as mathematically as if we were at the Pole itself, or the lives of millions depended on our adherence to routine.” In May 1881, two islands were discovered and named Jeannette and Henrietta. On the night of June 12, the pressure of the ice finally began to crush Jeannette. DeLong and his men unloaded provisions and equipment onto the ice pack and the ship sank the following morning.

The expedition now faced a long trek to the Siberian coast, with little hope even then of rescue. Nonetheless, they headed for the Lena Delta hauling their boats and supplies. After reaching several small islands in the Siberian group and gaining some food and rest, they took to their boats in hope of reaching the mainland. As a violent storm rolled in, one of the boats capsized and sank. The other two, commanded by DeLong and Chief Engineer George W. Melville, survived the severe weather, but landed at widely separated points on the delta. The party headed by DeLong began the long march inland over the marshy, half-frozen landscape to look for native settlements, but one by one the men died from starvation and exposure. Finally, DeLong sent the two strongest men ahead for help, and though they eventually found a settlement, DeLong and his companions died on the Siberian tundra.

In the meantime, Melville and his party found a native village and were rescued. Melville then headed for Belun, a Russian outpost, where he found the two survivors of DeLong's boat and persuaded a group of natives to go with him in search of his commander. He succeeded in finding their landing place on the Lena and recovered Jeannette's log and other important records, but returned to Belun without locating DeLong. Keeping only two of his party, Melville then turned northward once more, and finally found the bodies of DeLong and his two companions on March 23, 1882. He built a large marker over the grave of his friends, a monument which has been reproduced in granite and marble at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Before leaving Siberia, Melville made an attempt to find the remains of Jeannette's third boat, even though the chance of survivors was slim. He returned disappointed to Irkutsk, the capital of Siberia, on July 5, 1882, almost three years since his departure from San Francisco in Jeannette. The results of the expedition, both meteorological and geographic, were important. Melville was rightly honored for his courage and tenacity, and the name of George Washington DeLong is enshrined forever among the ranks of the U.S. Navy's explorer heroes. For more on polar exploration in the Navy, visit NHHC’s website.