Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On June 14, 1777, Captain John Paul Jones was ordered to take command of the 18-gun Continental Navy sloop Ranger. After fitting out at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Ranger hoisted her sails for France to deliver the news to the commissioners in Paris of the surrender of British General John Burgoyne’s troops at Saratoga, New York—considered a turning point for the young nation during the American Revolution. On the voyage over the Atlantic, Ranger captured two British prizes, which Jones sold when he arrived at Nantes on Dec. 2. While in France, on Feb. 14, 1778, Ranger received the first official salute to the new American flag, the “Stars and Stripes,” given by the French fleet at Quiberon Bay.

On April 10, Ranger sailed from Brest for the Irish Sea, and four days later, captured a prize between the Scilly Isles and Cape Clear. On April 17, she took another prize and sent that captured British vessel back to France. About a week later, Jones led a daring raid on the British port of Whitehaven, spiking the guns of the coastal batteries and burning the ships in the harbor. Several British cruisers were searching for Ranger as Jones sailed across the North Channel to Carrickfergus, Ireland, to persuade HMS Drake (20 guns) to come out of port and fight. Drake ventured out slowly against the wind and tide, and, after an hour's battle, the battered British vessel struck her colors. Having made temporary repairs, and with a prize crew on Drake, Ranger continued around the west coast of Ireland, capturing a stores ship, before arriving back at Brest with her prizes on May 8.

After he arrived in France, Jones was gifted the French vessel Duc de Duras by King Louis XVI for use against the British. Jones renamed the ship Bonhomme Richard to honor his friend, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, whose famous work, Poor Richard’s Almanac, was a bestseller in France under the title Les Maximes du Bonhomme Richard. Jones received command of Bonhomme Richard from Gabriel de Sartine, French minister of marine, in the spring of 1779. After several months of refitting the ship to a man-of-war, Jones was tasked with supplying her armament and manning the crew. Despite suffering from an adversarial relationship with his subordinates during his last voyage as commander of Ranger, the officers he selected for duty on Bonhomme Richard remained relatively loyal to Jones.

Bonhomme Richard set sail from L’Orient on June 19, 1779, as flagship of a squadron made up of 36-gun frigate Alliance, three French warships, and an 18-gun cutter taken from the British. On Sept. 23, at about 3 p.m., a lookout spotted a large group of ships approaching from the north. Guided by information he had received previously, Jones concluded that the vessels belonged to a 41-ship convoy coming from the Baltic Sea under the protection of British frigate Serapis and sloop-of-war Countess of Scarborough. Eager to confront them, Jones ordered maximum sail to close in on the enemy, but the wind was still very light and some three-and-a-half hours passed before they reached within striking distance. Meanwhile, British Captain Richard Pearson, commanding the convoy from Serapis, eyed the approaching ships suspiciously. Since they were still too far away, he could not tell what nationality they were, and Jones was flying British colors as a lure to get them into range of his cannons. Pearson moved forward to determine the identity of the approaching squadron. As Jones closed in with two escorts, he raised signal flags for the rest of the squadron to form a line of battle. They not only ignored these orders, but turned away entirely and left Bonhomme Richard alone as she closed with Serapis. Keeping his British colors aloft, Jones closed in on Pearson’s ship. The British captain called out to him, via trumpet, “What ship is that?” Hoping to move in just a little closer, Jones responded that he was Princess Royal. Unconvinced, Pearson called out again “Where from?” and when he received no answer, he bellowed, “Answer directly or I’ll fire into you.” Jones gave his answer by hauling down the British colors and raising the flag of the American rebellion. Immediately, both ships unleashed full broadsides onto each other.

Pearson, who enjoyed a substantial advantage over Jones, worsened dramatically for Bonhomme Richard when two 18-pounders exploded early in the battle. The twin blasts tore a hole in the ship and killed or horrifically injured the gun crews. The situation only got worse when Jones realized the remaining four 18-pounders were too old and defective to risk using, so he ordered to abandon them as well. Jones, knowing he had no chance just blasting away with his now very inferior firepower, tried to maneuver close enough to board Serapis. While maneuvering, the two ships collided with Bonhomme Richard’s bow, striking Serapis’ stern. At this point, Jones realized his best chance was to get the two ships coupled together. He scrambled across the deck to grab the enemy’s forestay (rope connected to the primary mast) that had been cut and had fallen on the deck of Bonhomme Richard. Seizing it and tying it to his own ship, Jones managed to tie the two ships together in a deadly embrace. This took away Pearson’s superior firepower, because half of his guns were pointed away from Bonhomme Richard.

With the two vessels entangled, Jones crew went to work firing what guns they had left at Serapis’ rigging in hopes of disabling her, while simultaneously using small arms fire and grenades on the enemy ship. While Bonhomme Richard’s small arms were having a devastating effect on Serapis and her crew, the British cannons were as equally successful. During the third hour of the battle, Jones found himself with only three small 9-pounders left on the quarterdeck. Pearson, meanwhile, heard the screams of some of Jones crew who wanted him to surrender. “Have you struck? Do you ask for quarter,” Pearson called out across the deck of Bonhomme Richard. At that moment, Jones famously replied, “I have not yet begun to fight!” At 10:30 p.m., Pearson had enough and struck. It was a stunning victory for the Americans.

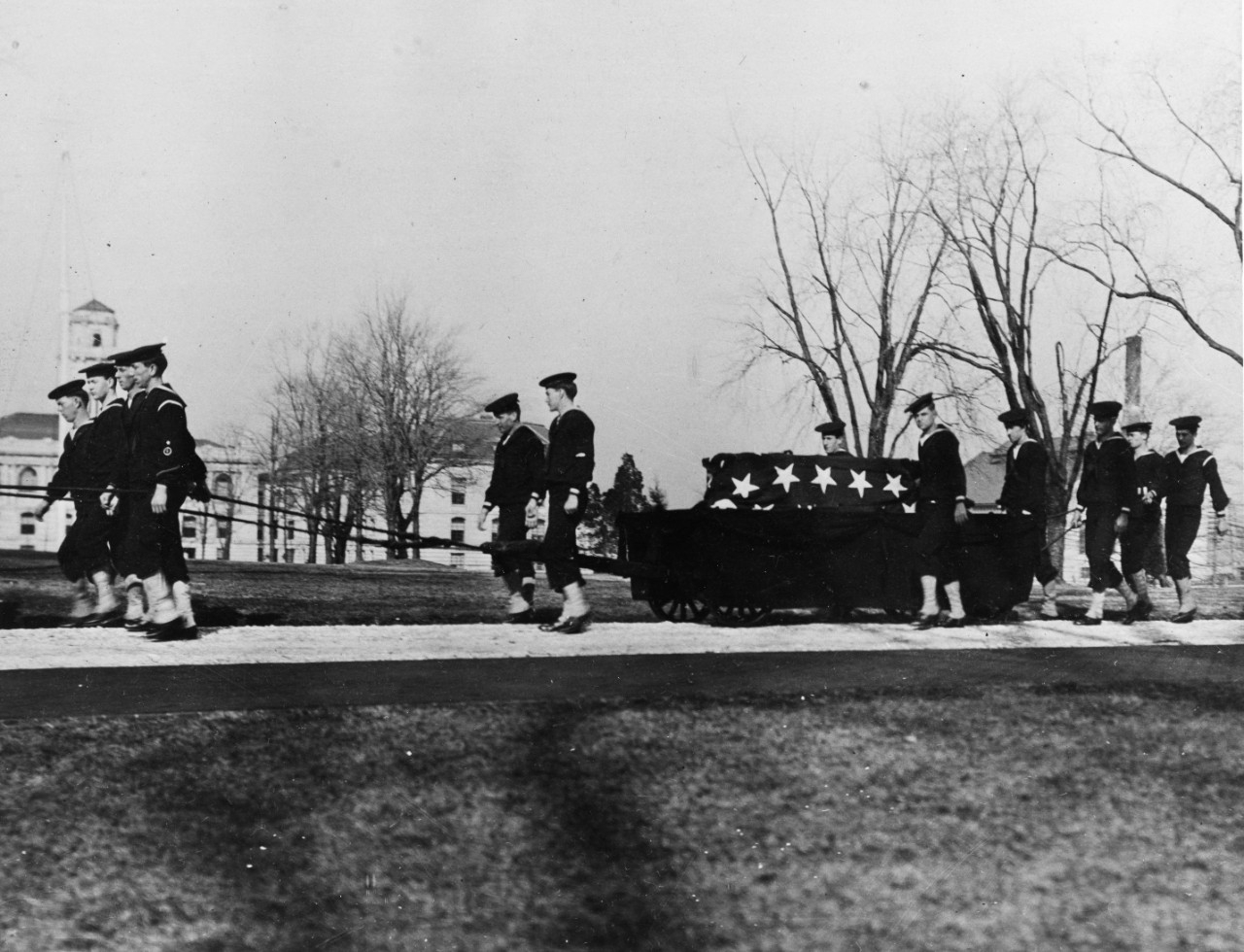

Jones is remembered for his indomitable will and his unwillingness to consider surrender. Throughout his naval career, Jones promoted professional standards and intensive training. Sailors of the U.S. Navy can do no better than to emulate the spirit behind Jones’s stirring declaration, “I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast for I intend to go in harm's way.” Jones passed away on July 18, 1792, at his residence in France. In 1905, Jones’s remains were identified by U.S. Ambassador to France Gen. Horace Porter, who had searched for his body for six years. The following year, his remains were transported back to the United States. On April 24, 1906, Jones’s coffin was installed in Bancroft Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, following a ceremony in Dahlgren Hall, presided over by President Theodore Roosevelt, who gave a speech paying tribute to the American hero. On Jan. 26, 1913, Jones’ remains were finally re-interred in a bronze and marble sarcophagus at the Naval Academy Chapel.

Battle of Saipan

Following intensive naval gunfire and bombing by carrier-based aircraft, Task Force 52 landed Marines of the 2nd and 4th Divisions on Saipan June 15, 1944. The island was the first relatively large and heavily defended land mass in the Central Pacific to be assaulted by U.S. amphibious forces. However, the assault was brutal for U.S. forces. Just before dawn on D-day, the Marines had a grand breakfast and then it was time to board the amphibian tractors. Fifty-six of these vehicles proceeded in lines of four toward the eight designated landing beaches. Thousands of Japanese personnel, with their artillery, held their fire as the tractors gained the reefs and arrived in the lagoon. Then, with a deafening roar of Japanese artillery, it became clear that the preparatory bombardment of the shoreline defenses had not done enough. Japanese defenses were hidden well in Saipan’s topography, which featured high ground within range of the lagoon and reefs, a natural obstacle for U.S. forces and a focal point for Japanese fire. Deadly complications besieged American forces all at once. The intensity of the enemy’s defense resulted in one landing area becoming overcrowded as Marines tried to get a footing on shore. The massive amount of U.S. personnel storming the beach was an easy target for Japanese mortars and other projectiles. Nevertheless, the Marines managed to get to dry ground before H-hour had passed. Then came another obstacle. The amphibian tractors were not functioning as had been planned. Their armor was not heavy enough to withstand the barrage from Japanese artillery, and their agility on the rough terrain proved lacking. Marines scattered in several directions as hilltop snipers tried to pick them off one by one. Eventually, the Americans reestablished order and proceeded with the assault.

The Japanese resistance was far greater than anticipated, as intelligence reports had underestimated Japanese troop levels. U.S. forces expected there to be about 31,000 enemy troops, but in reality there were about twice that many. For at least a month, the Japanese had been fortifying the island and bolstering its forces as well. U.S. D-day casualties were high, with as many as 3,500 in the first 24 hours, in spite of having 20,000 troops on shore by sunset with more to come. Reinforcements could not come quickly enough as the Japanese defense doubled down and changed tactics by deploying tanks and infantry in the darkness of night. Conditions improved the following day when a new group of battleships arrived to bombard the coast. In response to difficulties on the ground, U.S. forces postponed the invasion of Guam and the operation’s reserve, the Army’s 27th Infantry Division, was called in to assist the Marines.

The unexpected difficulties on the beaches prompted Adm. Raymond Spruance, Fifth Fleet commander, to commit more ships to the operation. Spruance had good reason to worry about the beachheads, although they appeared to be secured by the second day of the battle. “The [Japanese] are coming after us,” Spruance said, and they were bringing with them 28 destroyers, 5 battleships, 11 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 9 carriers with somewhere near 500 aircraft. The resulting engagement, Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20), was a decisive victory for the Allies that nearly eliminated the Japanese ability to wage war by air. Notably, during the operation known as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” the U.S. destroyed nearly 600 enemy aircraft, sank two enemy fleet carriers, a light carrier, and two oilers, killing nearly 3,000 of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s pilots and sailors.

After the Battle of the Philippine Sea was over, U.S. forces turned the main effort back to Saipan, where reinforcements and materiel were still needed as the battle still raged on. Attack transport Sheridan (APA-51) was among the first of the ships to return. For days, Sailors had been watching the action on the shore from Sheridan’s decks. This got easier to decipher at dusk when the tracers came out, according to Lt. j.g. Harris Martin. The Americans’ flamethrowers, too, shone brightly amid the carnage: “We could see some of our landing craft being hit by Japanese artillery and we watched Japanese tanks as they counterattacked from the low hills.” When the island was finally declared secure on July 9, the work of processing prisoners of war, both civilian and military, began. In addition, Navy civil engineers (Seabees) began to plan for the internment camp and ordered the construction of shelters and other facilities.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Saipan, tens of thousands of Japanese troops were killed and more than 1,700 were captured. Particularly shocking were the extensive civilian casualties, estimated to be as high as 22,000. Civilians, as well as Japanese military personnel, reportedly opted to commit suicide by jumping off cliffs rather than be captured by the Americans. The Americans suffered greatly as well, with 26,000 casualties—about 5,000 of those were killed in action. However, the American victory on Saipan was decisive. Japan’s National Defense Zone, demarcated by a line that the Japanese had deemed essential to hold in the effort to stave off a U.S. invasion, had been blown open. Japan’s access to scarce resources in Southeast Asia was now compromised, and the Caroline and Palau islands now appeared to be ready for the taking. With Saipan’s airfields soon to be operational (as well as those of Tinian and Guam, which the Americans would capture a short time later) and with Japanese air power having been all but eliminated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, there was little protection for the home islands from Allied aerial bombardment.

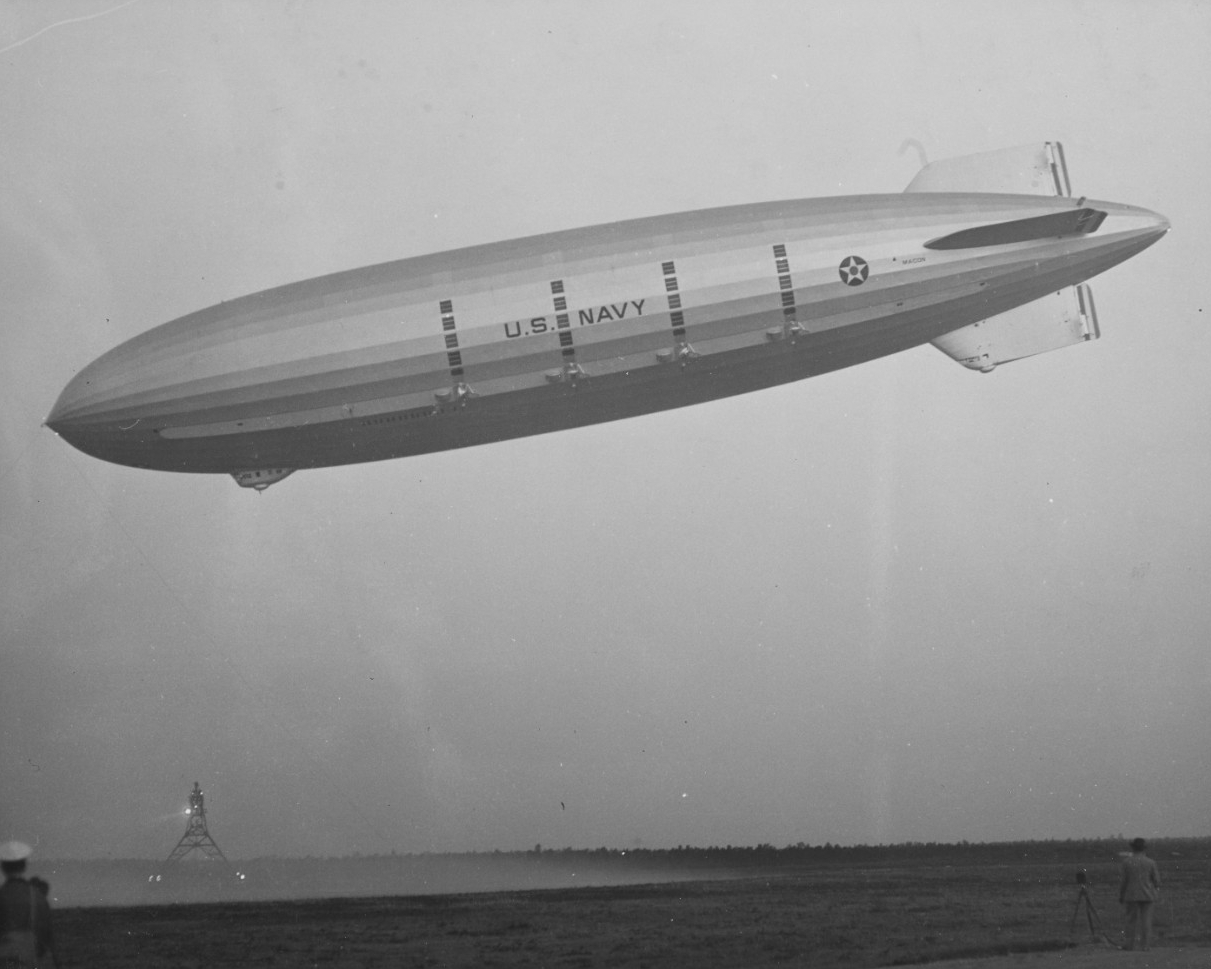

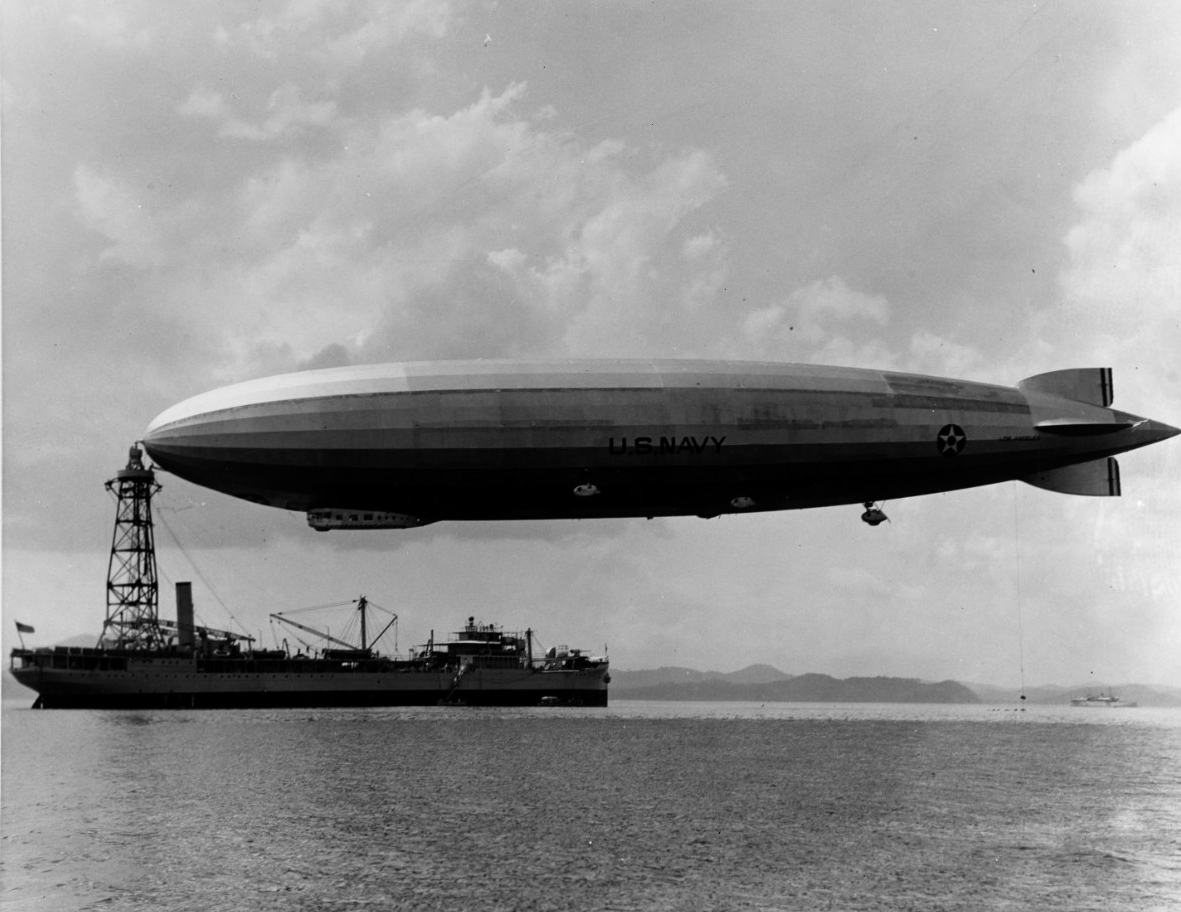

Macon Commissioned

Rigid frame airship Macon (ZRS-5) was commissioned on June 23, 1933. At the time, rigid airships were considered an improvement from previous designs because they could carry aircraft. Macon was capable of carrying five Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplanes. Macon received her first aircraft on July 6, 1933, during trial flights out of NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey. Departing the U.S. East Coast on Oct. 12, 1933, Macon's home field became Sunnyvale, California. She operated out of that base until Feb. 12, 1935, when, returning from fleet maneuvers, she ran into a storm off Point Sur, California. During the storm, she was caught in a sudden updraft, which caused structural failure of her upper fin, resultant gas leakage, and loss of control. Settling to the sea, Macon sank off the California coast, losing two crewmembers. Of note, the only surviving Sparrowhawk from Macon is currently on loan from the National Naval Aviation Museum to Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum.

Macon, having completed 50 flights from her commissioning date, was stricken from the Navy list on Feb. 26, 1935. Subsequent airships for Navy use were of a non-rigid design to make them less vulnerable to poor weather. There were just a handful of rigid frame airships built by the Navy. Akron (ZRS-4) was also lost to weather when she crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off the New Jersey coast on April 4, 1933. The incident killed 72 of her crewmembers to include Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, who was the leading proponent of rigid frame airships.

The Navy had first launched its lighter-than-air program when it awarded its first contract for an airship, DN-1, to the Connecticut Aircraft Company in June 1915. The designation stemmed from “D” for dirigible, “N” for non-rigid and “1” as the Navy’s first airship. During construction of DN-1, the Navy authorized construction of a hangar to house the new airship, which was completed in early 1916. DN-1 arrived in Pensacola, Florida, in December 1916, but the airship was not ready for flight until April 1917. Once test flights began, multiple problems were revealed. The airship was severely damaged during one of the test flights and it was never repaired.

Even before DN-1 was built, studies were ongoing at the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a future class of dirigibles. The General Board endorsed the development of “zeppelins” (rigid frame airships) and other mobile lighter-than-air craft. At Akron, Ohio, the Navy’s program tested non-rigid airships, free balloons, and kite balloons. During testing, the balloons were found to be an easy target for enemy aircraft and restricted maneuverability when moored to a ship. However, during World War I, airships and kite balloons were used in conjunction with seaplanes and flying boats to help protect shipping. They were also used to detect submarines and warn vessels of mines. Most of the airship patrols were carried out off the U.S. East Coast and in European waters, where they were deemed successful because they were a deterrent to German submarines.

After the “Great War,” the development of non-rigid airships became more advanced with more capabilities. The Navy contracted Goodyear to build airships and hangers to accommodate them. The airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) was the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium and the first to fly across the United States. On Sept. 3, 1925, while flying over Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a severe storm that broke the airship in two killing about half the crew. The most successful airship of the time was Los Angeles (ZR-3). The airship was built by Germany and given to the U.S. as compensation for the loss of two airships that were lost during the war. Los Angeles was in operation about seven years and made more than 330 flights.

During World War II, there were five different airship classes/types in the Navy’s inventory. Airship operations and expansion was unprecedented. The airship fleet conducted operations in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and Atlantic. When the war was over and the military drew down, the Navy still kept two squadrons that primarily conducted training, search and rescue, observation, and photography missions.

On June 21, 1961, the Secretary of the Navy announced he was going to terminate the Navy’s lighter-than-air program. The last flight of a naval airship occurred on Aug. 31, 1962.

Brave Sailor Defied Hijackers

On June 14, 1985, Steelworker Second Class Robert D. Stethem was tortured and killed by Hezbollah terrorists, who had hijacked TWA flight 847. Stethem was flying home from Athens, Greece, with 153 passengers when the terrorists took over the plane and forced it to fly to Algiers, where they demanded the release of 435 Arab prisoners held by Israel. When the terrorists’ demands were not met, they forced the airplane to fly to Beirut, Lebanon. While in Beirut, their demands for fuel were also refused. The passengers’ passports were collected and when Stethem was identified as a U.S. Sailor, he was bound with rope and beaten in an attempt to force him to scream into a transmitter, so that the tower would send fuel. However, Stethem steadfastly refused to cry out as he was beaten and tortured for several hours. Not a cry was heard from him as he endured the beating. Instead, he chose to remain silent because he knew that the only way a rescue attempt could be conducted was if the aircraft remained on the ground. Ultimately, because of his silence, he was shot and killed by an enraged terrorist. The pilot was later asked about his impression of Stethem and he replied simply, “He was the bravest man I've ever seen in my life.” For 17 days, the hijackers kept the passengers hostage before giving in and releasing them.

Stethem was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for heroism. In 1995, the destroyer USS Stethem (DDG-63) was named in his honor. On Aug. 24, 2010, onboard Stethem in Yokosuka, Japan, Stethem was made an honorary Constructionman Master Chief Petty Officer by the Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy. Stethem is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Stethem was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, and raised in Waldorf, Maryland. He was one of three sons. Shortly after graduating from Thomas Stone High School in 1980, he joined the Navy, where he was trained as a diver and as a steelworker. He was assigned to the Navy Underwater Construction Team 1 in Norfolk, Virginia, and in 1985, the team was sent to Greece to repair a Navy communications facility.

One of Stethem’s brothers said in reflection of his brothers’ sacrifice, “Every time I look at the flag now and for the rest of my life, the red will represent the blood he spilled, the blue the beating and bruises he endured, and the white the purity and integrity he demonstrated in sacrificing his life.”