Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

How a Community Came Together to Save The Sullivans

In just eight months, the Buffalo and Erie County Naval & Military Park managed to raise more than $1 million for desperately needed repairs for decommissioned 1943 destroyer USS The Sullivans. In recent years, the park has repaired small holes in the hull every spring, but harsh winter weather and the pandemic-related shutdown hastened the damage. Water was seeping into the leaky hull, causing the ship to list to port. Contributions to save the ship came from 26 states and seven countries. Donors ranged from a 4-year-old boy, who made two contributions of $4, to the foundation Save America’s Treasures, which contributed $499,000. “We’ve been through some tough times these last few years, and to see people be so generous, it makes you emotional,” said Kelly Sullivan, a third-grade teacher and granddaughter of the only Sullivan brother who married. The ship was named to honor a working-class family that lost all five of its sons aboard USS Juneau 79 years ago, when it was struck by a Japanese torpedo that killed most of her crew in the Solomon Islands. Developer Douglas Jemal, who initially donated $10,000 and held a fundraiser that raised another $85,000, noted that the future of USS The Sullivans is about more than just saving a National Historic Landmark. It’s about honoring the sacrifices of the Sullivan family, and the 400,000 other Americans who died for our freedoms during World War II. For more, read the article.

Japanese Armada Departed Japan to Attack Pearl Harbor—80 Years Ago

On Nov. 26, 1941, under the greatest secrecy, a Japanese armada—commanded by Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo—left Japan to attack Pearl Harbor. The armada included all six of Japan’s first-line aircraft carriers—Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku. With 353 embarked aircraft, it was by far the most powerful carrier task force ever assembled. In addition to the carriers, the Pearl Harbor striking force included fast battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, with tankers to fuel the ships during the passage across the Pacific. An advance expeditionary force of large submarines, five of them carrying midget submarines, was sent to scout around Hawaii. Their mission was to dispatch the midget subs into Pearl Harbor to attack ships there and torpedo American warships that might escape to sea.

Preble Hall Podcast

In a recent naval history podcast from Preble Hall, Stephen Phillips and author Stan Haynes discuss Hayne's historical novel, And Tyler No More, which includes a historically accurate account of screw steamer Princeton, the ship's technological innovations, and an ordnance accident that killed the Secretary of State, the Secretary of the Navy, and but for a song, likely would have killed President John Tyler. The Preble Hall podcast, conducted by personnel at the U.S. Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, MD, interviews historians, practitioners, military personnel, and other experts on a variety of naval history topics from ancient history to more current events.

Sailor Donated Admiral Joseph “Jocko” Clark Memorabilia to Cherokee Nation

This month, as the country celebrates National American Indian Heritage Month, the U.S. Navy finds itself at a cultural crossroads between its own proud history and the equally proud lineage of the Cherokee Nation. Members of the Navy and the Cherokee Nation came together recently at the Army Navy Club in Washington, DC, to remember and honor a proud Native American and Sailor, Joseph James “Jocko” Clark. During the ceremony, Vice Adm. Jeff Trussler, a Cherokee Nation member, who currently serves as the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Information Warfare (N2N6) and as the Director of Naval Intelligence, presented a naval cruise book that once belonged to Clark to Kimberly Teehee, the Cherokee Nation delegate-designate to Congress, who accepted the cruise book on behalf of the nation. “I am honored to represent the U.S. Navy at this event to honor the memory and career of a true Navy warfighting hero of World War II… Admiral Joseph James “Jocko” Clark,” said Trussler. “The timing of this ceremony couldn’t be any better as it coincides with our annual commemoration of National American Indian Heritage Month. Coincidentally, today also happens to be the anniversary of the admiral’s birth, Nov. 12, 1893. His life and career of service to our Navy and our nation are worth remembering—he set the standards for those of us who share that heritage and who have followed in his footsteps.” For more, read the article by NHHC’s MC2 Ellen Sharkey. For more on the Contributions of Native Americans to the U.S. Navy, visit NHHC’s website.

Libby Relieved Burke as UN Delegate—70 Years Ago

On Nov. 26, 1951, during the Korean War, Rear Adm. Ruthven E. Libby relieved Rear Adm. Arleigh Burke as the United Nations delegate to the Panmunjom Peace Talks. In July 1951, Burke was made a delegate to negotiate with the Communists for a military armistice in Korea. However, after six months of frustration in the truce tents, he returned to the Office of Chief of Naval Operations. Libby experienced the same frustration. Negotiations for the armistice spanned more than two years, the longest negotiated armistice in history. Over those two years, representatives from United Nations Command, the Korean People’s Army (KPA), and Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (CPVA) met in Kaesong and later, Panmunjom. There were 158 meetings before any of the parties agreed to sign the document. During the meetings, all parties sought to make an agreement that would suspend open hostilities, arrange the release and repatriation of prisoners of war, and establish a separation of forces. In the final meeting, the armistice agreement accomplished those goals and established the Military Armistice Commission, as well as other commissions to oversee the truce terms and negotiate settlement of any armistice violations. Additionally, the armistice established the peninsula-wide demilitarized zone to provide a buffer between military forces.

Liscome Bay Lost

On Nov. 24, 1943, Japanese submarine I-175 sank USS Liscome Bay southeast of Makin Island. Although 272 were rescued, the ship lost more than 600 of her crew, including Navy Cross recipient Cook 3rd Class Doris “Dorie” Miller. Miller had previously received the Navy Cross from Adm. Chester W. Nimitz for heroism onboard USS West Virginia during the Pearl Harbor attack. After carrying several wounded Sailors to safety, including the ship’s captain, Miller manned a Browning antiaircraft machine gun—on which he had no training—and proceeded to fire on the enemy until he ran out of ammunition and was ordered to abandon ship. Miller was assigned to Liscome Bay in the spring of 1943 and was aboard the escort carrier during Operation Galvanic, the seizure of Makin and Tarawa Atolls in the Gilbert Islands. A single torpedo hit the ship, detonating the aircraft bomb magazine, while the escort carrier was cruising near the Tarawa Atoll’s Butaritari Island. Liscome Bay sank within minutes.

Namesake’s Grandson Visited USS Winston S. Churchill

After recently attending a change of command ceremony on board USS Winston S. Churchill, at BAE Systems Shipyard near Jacksonville, FL, the Honorable Rupert Soames toured the ship. Soames is the ship’s sponsor and grandson of the ship’s namesake—World War II British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill. “It’s always a fantastic time for any ship to have its sponsor aboard,” said Cmdr. Brian Anthony, the Churchill’s commanding officer. “It was a great honor for us to update the Honorable Mr. Soames on Churchill, the challenges and successes of its crew. I am delighted to demonstrate how it continues to deliver as the Navy’s most combat ready ship.” Soames is also the Group Chief Executive Officer of SERCO, a company that has approximately 60 employees working on Winston S. Churchill’s depot modernization project. “My grandfather would be immensely proud of this ship and all who have sailed, are now sailing, or will sail in her,” said Soames. “USS Winston S. Churchill represents all that is right between our countries, and she is a fine global ambassador of peace and naval power.” For more, read the U.S. Navy press release.

Webpage of the Week

This week’s Webpage of the Week is the Navy Thanksgiving page. The U.S. Navy has celebrated Thanksgiving in one fashion or another even before it became an official American holiday. Arrayed on this page are selected Navy Thanksgiving menus from NHHC’s collections that span the first half of the 20th century. Although some dishes, such as “Mayonnaise Salad” on battleship Arizona in 1917, and “Baked Spiced Spam à la Capitaine de Vaisseau” on cruiser Augusta in 1942, have not transcended time, roast turkey, baked ham, and pumpkin pie have been the anchors of nearly every Thanksgiving feast at sea or on shore to the present day. Check this page out today. Happy Thanksgiving!

Today in Naval History

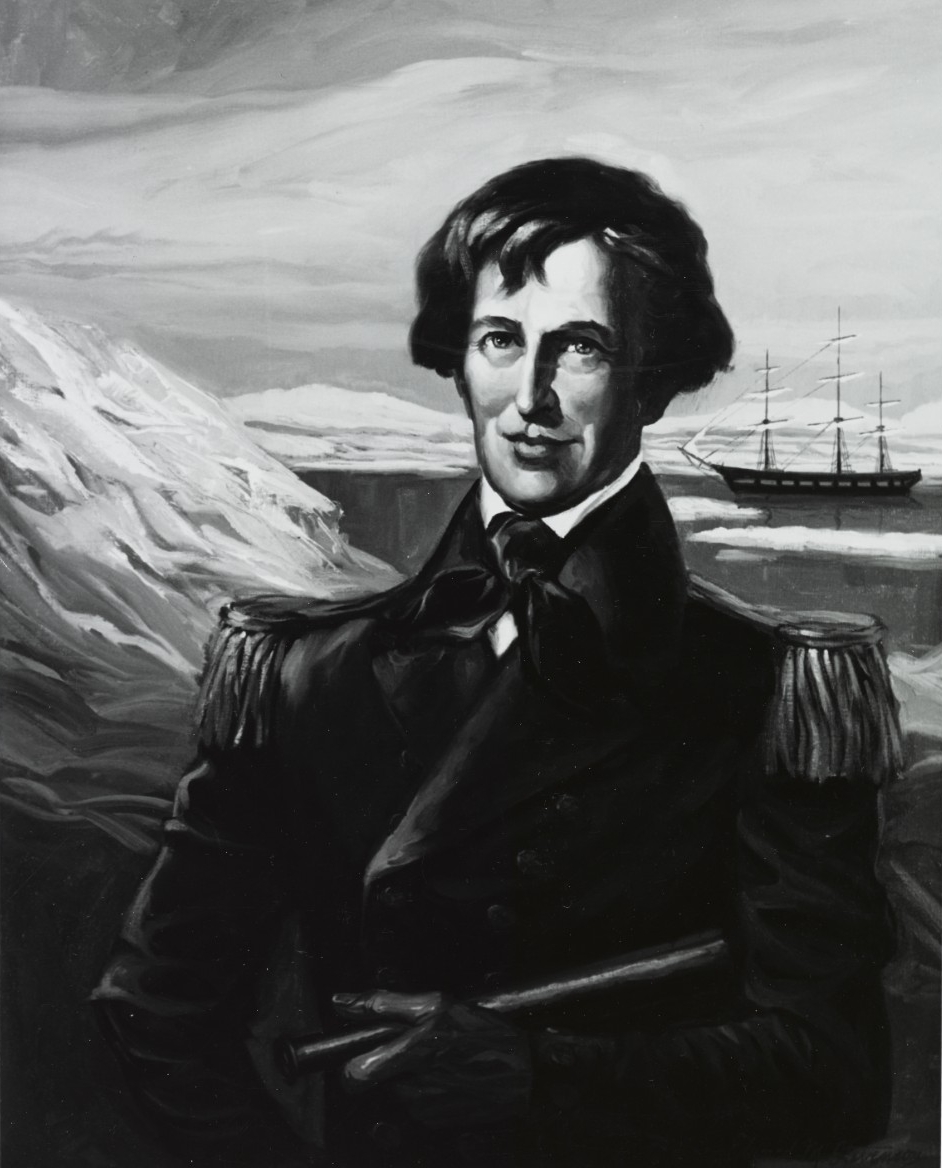

On Nov. 23, 1838, sloop-of-war Vincennes reached Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, en route to the South Pacific during the U.S. Exploring Expedition. The four-year expedition, commonly referred to as the Wilkes Expedition, was led by Lt. Charles Wilkes, and its purpose was to study and survey the Pacific Ocean from north to south. In company with Peacock, Porpoise, Sea Gull, Flying Fish, and Relief, the expedition made its second stop at Tierra del Fuego, located at the southern tip of South America, and then made its first cruise through Antarctic waters, February–March 1839. They returned to Tierra del Fuego, and then later headed through the South Seas to Sydney, Australia, where they arrived in late November. On the day after Christmas, they embarked on their second voyage to the Antarctic. In January 1840, Wilkes sighted the actual land mass that constitutes Antarctica, though it took later explorations to confirm the continent existed. By late spring 1840, the expedition moved north again and began the exploration of the islands of the South Pacific. After surveying the Fiji Islands between May and August, the expedition made way to Hawaii. The Hawaiian survey centered on studying the volcanoes Mauna Loa and Kilauea. In April 1841, they set sail for the U.S. West Coast. After surveying parts of the coast of the Pacific Northwest during the summer of 1841, Wilkes brought the expedition into San Francisco on Aug. 14. Their arrival back in the United States, however, signaled no end to the work of the expedition. On Nov. 1, they were at sea once again, this time for a voyage to the Western Pacific. During that cruise, the expedition visited Manila in the Philippines, the British colony at Singapore, and Cape Town on the southern tip of Africa. Wilkes’ expedition concluded upon arrival at New York on June 10, 1842.

For more dates in naval history, including your selected span of dates, see Year at a Glance at NHHC’s website. Be sure to check this page regularly, as content is updated frequently.