Liscome Bay (CVE-56)

1943

A bay off the eastern coast of Dall Island in southeast Alaska.

(CVE-56: displacement 7,800; length 512'3"; beam 65'0"; extreme width (flight deck) 108'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 19 knots; complement 860; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40-millimeter., aircraft 28; class Casablanca)

Laborers employed by the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company in Vancouver, Washington laid the keel of M.C. hull 1137 on 12 December 1942. Initially, the escort carrier was to pass into the hands of the British as HMS Ameer, and on 19 April 1943, Mrs. Clara Klinksick, wife of Rear Adm. Ben Moreell, USN, christened the escort carrier with champagne honors. By late-June 1943, however, Navy officials decided to maintain possession of the “baby flattop,” renaming the vessel Liscome Bay—after a bay in southeast Alaska. The Navy redesignated her CVE-56 on 15 July 1943 and commissioned her on 7 August 1943, Capt. Irving D. Wiltsie in command.

Liscome Bay (CVE-56) moored at Naval Station Astoria, Oregon one month after commissioning, 2 September 1943. U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-391023, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, MD.

Civilian tugs guided Liscome Bay down the Columbia River to the Naval Station at Astoria, Oregon, to complete her fitting out on 30 July 1943. Rear Adm. Henry M. Mullinnix reported for duty as prospective Commander Carrier Division (CarDiv) 24 on 29 August 1943. The other ships that made up the division included Coral Sea (CVE-57), Corregidor (CVE-58), and Manila Bay (CVE-61). Throughout September, CarDiv 24 underwent inspection at the Bethlehem Ship Building Yard in San Pedro, Calif., following shakedown trials, operational training, and post-shakedown repairs. All ships in CarDiv 24 then converged at San Diego to load cargo, ordnance, thousands of gallons of fuel, and aircraft.

Liscome Bay’s Composite Squadron (VC) 39 had eleven General Motors FM-1 Wildcats, five Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats, nine General Motors TBM-1 Avengers, and three General Motors TBM-1Cs. Coral Sea’s VC-33 had twelve F4F-4s and ten Grumman TBF-1C Avengers, while Corregidor’s VC-41 had twelve FM-1s and nine TBF-1s.

On 11 October 1943, Rear Adm. Mullinnix assumed command of CarDiv 24, breaking his flag in Liscome Bay and making her his flagship. Ten days later, Liscome Bay was the first of the group to depart for the Territory of Hawai’i. While at Pearl Harbor, Liscome Bay took on additional stores, which included Thanksgiving turkeys—indicating to the anxious crew that they would not be returning to the mainland anytime soon. On 10 November 1943, CarDiv 24 departed Pearl Harbor in company with other units of Task Force 52 and proceeded west for an offensive against the Gilbert Islands in Operation Galvanic. For a more in-depth analysis of Operation Galvanic, see NHHC’s recent publication, Galvanic: Beyond the Reef, Tarawa and the Gilberts (November 1943).

As “baby flattops,” some of the earliest escort carriers—initially classified as “aircraft escort vessel" (31 March 1941), then “auxiliary aircraft carrier” (20 August 1942)—entered the fleet as converted C-3 merchant hulls with the addition of a flight deck. Early in the war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt saw value in acquiring merchant ships and oilers for conversion to “aircraft carrier, small” with the intention that CVEs would escort vulnerable convoys to the Pacific and provide air support. The Casablanca-class flattops, of which Liscome Bay was one, were approximately three hundred feet shorter than those of their contemporary Essex-class sisters. Sailors bestowed a range of monikers to the Navy’s fleet of convoy escorts, ranging from the innocuous to the provocative, even mocking. The hastily built warships, with the hull designation CVE, were often described by members of their cynical crews as “combustible, vulnerable, expendable.” Their cynicism was not without merit, as events would bear out.

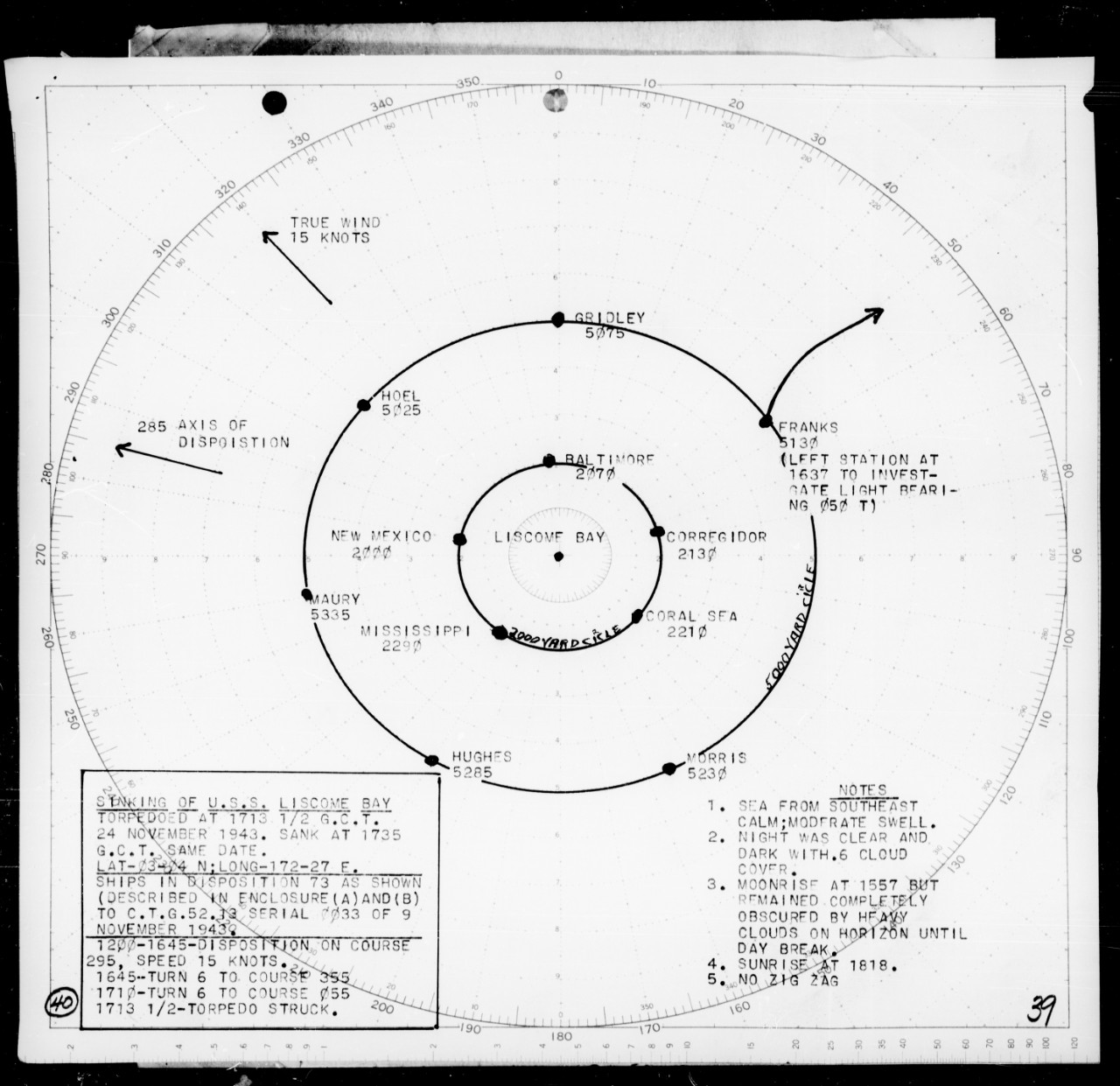

USN ship disposition on the night of 24 November 1943. Reprinted from L. L. Hunter to R. M. Griffin, memorandum, “The Sinking of the U.S.S. LISCOME BAY,” December 5, 1943, World War II War Diaries and Other Operational Records and Histories, Record Group 38: Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD [hereafter WWII War Diaries, RG 38, NARA].

The invasion bombardment of Tarawa and Butaritari atolls began the morning of 20 November 1943, with aircraft from Liscome Bay flying 2,278 sorties in support of Marine landings and combat operations, as well as intercepting enemy aircraft, spotting for naval gunfire support, and conducting antisubmarine patrols. As ground combat tailed off by 23 November, the temporary task group built around Liscome Bay, Coral Sea, and Corregidor—commanded by Rear Adm. Robert M. Griffin in battleship New Mexico (BB-40)—steamed in patrol pattern twenty miles southwest of Butaritari atoll. Unbeknownst to the task group, the Japanese submarine I-175, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Tabata Sunao, arrived in the Gilbert Islands late that night.

On 24 November 1943, reveille sounded for all hands on board Liscome Bay at the usual time of 0430. Among those wiping the crust of sleep from their eyes that morning was Navy Cross recipient Ck3c. Doris “Dorie” Miller. A resident of Waco, Texas, Miller enlisted in the Navy as a mess attendant third class in May 1939 at the age of nineteen. After completing training in Norfolk, Virginia, Miller came on board West Virginia in August 1940. During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, “despite enemy strafing and bombing,” Miller assisted his shipmates in moving their mortally wounded captain to relative safety and, without orders, “operated a machine gun directed at enemy Japanese attacking aircraft.” What made Miller’s handling of West Virginia’s Browning .50-caliber machine gun meritorious was his inexperience with the weapon. Miller, like most of the ship’s complement of Black sailors, did not receive training in the operation of deck weapons. On board Liscome Bay, however, Miller manned one of the carrier’s port side 20-millimeter guns assisted by loader StM1c. Theodore R. Harris while at general quarters.

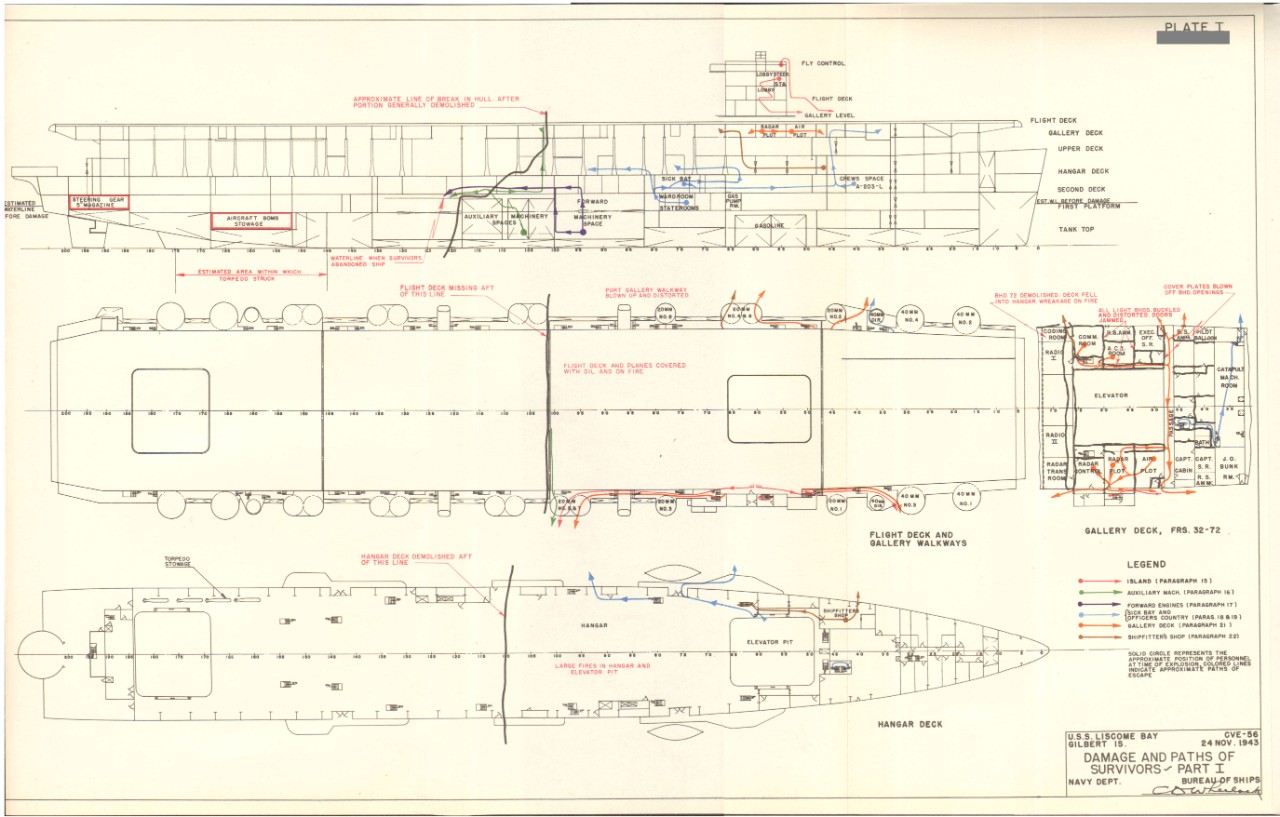

Liscome Bay sounded general quarters thirty-five minutes after reveille not because the SG radar on board the accompanying battleship New Mexico picked up a suspicious return, but because experience had shown that the transition between night and day was an excellent time for enemy air attacks, given the difficulties lookouts had spotting enemy aircraft in the dim light. For general quarters to sound at this time of day, therefore, was not uncommon for ships at war. Within five minutes of sounding general quarters, however, a Japanese torpedo slammed into Liscome Bay abaft of the after engine room. Following a short interval, wrote the senior surviving officer Lt. Cmdr. Oliver Ames, A-V(T), USNR, “a second major detonation closely followed . . . a series of detonations of lesser intensity” further aft. The blasts, likely caused by the detonation of a bomb storage magazine, immediately cut power cables and broke water pipes across the ship. A wall of flames consumed the hangar deck and pockets of smaller fires broke out on the flight deck above. Aviation fuel and oil pooled on the surface of the water under the starboard bow and ignited.

Action shot of the explosion of Liscome Bay as photographed from Mississippi, 24 November 1943. U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-227956, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, MD.

A plume “of bright orange-colored flame, with some white spots in it like white hot metal” disrupted the calm of the early morning Pacific sky. American sailors in neighboring ships confirmed seeing a column of flame emanating from Liscome Bay, but their reports differed over the number of explosions they witnessed—some claimed one, while others asserted they observed two rapid-succession explosions. This was likely because aircraft and antiaircraft ammunition, ordnance, and depth charges detonated indiscriminately in the aft hull of the disabled vessel. Liscome Bay survivors stationed in the auxiliary and forward engine rooms at the time of the incident “reported one violent explosion followed by one or two less violent shocks.” Within seconds, at some 1,500 yards distance, burning and smoldering debris fell on New Mexico. The battleship’s commanding officer, Capt Ellis M. Zacharias, reported his vessel “was showered from forecastle to quarterdeck with oil particles and burning and extinguished fragments [of] deck splinters up to three feet in length, metal fragments in great numbers—mostly small but as large as one pound in weight—molten drops of metal, bits of clothing, dungarees, overshoes, and so forth, and several pieces of human flesh.” New Mexico, as with the other ships in formation, had no capability to engage the submerged I-175 as Tabata retreated.

“Plate I: Damage and Path of Survivors” reprinted from Navy Department Bureau of Ships, U.S.S. Liscome Bay (CVE56) Loss in Action: Gilbert Islands, Central Pacific, 24 November 1943 (U.S. Hydrographic Office: Washington DC, 1944). While it cannot be confirmed, it is likely that Dorie Miller was at the starboard 20-millimeter antiaircraft gun between frames 155 and 145 at the time of the explosion.

Tabata had managed to guide I-175 toward the American task group undetected, despite the use of radar technology by some of the ships in CarDiv 24. Lurking submerged just beyond the screening destroyers, Tabata launched a spread of four Type 93 torpedoes at the task group, hoping at least one made contact with an American warship. The 24-inch torpedoes used pure oxygen to propel the weapon forward, replacing previous models that used compressed air and eliminating “practically all gas bubbles, leaving only a slightly visible wake.” While standing at his battle station at one of the 40-millimeter guns on the starboard quarter, Ens. Thomas D. Yuill, D-V(G), USNR, identified the unmistakable bubbling wake of an incoming torpedo. According to Ens. Francis X. Daily, Jr., D-V(G), USNR, in his unpublished memoirs and reprinted in Twenty-Three Minutes to Eternity, seconds before the torpedo made contact with Liscome Bay, Ens. Yuill shouted into his telephone to the bridge: “Christ, here comes a torpedo!” Nearly every sailor at battle stations aft of the auxiliary machinery spaces was killed instantly. There were no survivors aft of frame 118, the final War Damage Report noted.

Thirteen aircraft—ready to depart for morning flight operations—were visible on the flight deck with one forward on the catapult. The readiness of these planes meant that flight crews had completed the fueling and arming process, making them especially flammable and susceptible to combustion. Ames speculated that flames “spread with tremendous rapidity throughout the ship, probably because of oil and gasoline in the planes on deck.” An eyewitness, Ens. Danten D. Creech, D-V(G), USNR, observed the explosion through his binoculars from the deck of Coral Sea. Creech confirmed seeing planes on the flight deck “blown into the air and overturned by the first explosion. Before the flames of the first explosion had come down, the entire flight deck burst into flames.” Survivors already in the water bore witness to the sobering sight of their baby flattop ablaze with “little structure remaining at the stern.” Ten sailors assigned to the gyro room, second deck machine shop, generator room, and electrical workshop were the ship’s aftmost survivors.

Scores of men sprinted to the valves that controlled the water lines to Liscome Bay’s fire hoses and despite their valiant efforts to increase water pressure, the gauges never registered above zero. The broken cast iron water pipes and valves, shattered in the explosions, were undoubtedly a result of mass production techniques in building these escort carriers. Never meant for fleet carrier combat operations, and designed for quick, cheap construction, the escort carriers did not include the redundant steel water pipes, and backup electrical and firefighting systems found on the more durable Essex-class fleet carriers. Without the ability to broadcast the order to abandon ship, the order passed from sailor to sailor by word of mouth. Capt. Wiltsie was last seen by Lt. Cmdr. Marshall U. Beebe ordering those around him to abandon ship while beckoning survivors to the safest route to the water. Sailors watched, dazed, as Liscome Bay listed to starboard, taking on water, and, twenty-eight minutes after the initial explosion, she sank below the surface.

Destroyers Morris (DD-417), Hughes (DD-410), and Hull (DD-350) initiated rescue operations immediately. Hughes’ commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. Ellis B. Rittenhouse, confirmed seeing survivors “jumping off the flight deck into the water, one group of about five men jumping with a rubber boat which tumbled after them. This group,” he continued, “appeared to land directly into flaming oil which seemed to cover the area all along the starboard side and around the bow.” Rittenhouse supervised the rescue of survivors from the water at 0600. The crew lowered a life raft on which Liscome Bay sailors rested before being taken on board. Survivors incapable of walking “were brought on board by the use of hammocks” lowered over the port side. “This was a big help in the case of wounded men,” Rittenhouse concluded, “for they could be placed on hammocks much easier from the raft than directly from the water.” A motor whaleboat made three trips to retrieve survivors with Hughes’ pharmacist’s mate on board to administer first aid. The crew also converted the after mess hall to a temporary sick bay and triage center. Burns were the most severe injuries treated by medical staff. Ad hoc “burn teams,” consisting of non-medical assistants, removed thick coatings of fuel oil, cleaned burns, and applied sulfa powder or boric acid ointment dressings. Survivors capable of showering had “to rid themselves of fuel oil” at cleaning stations equipped with “diesel oil and clean rags.” The supply officer then dispensed gum, cigarettes, underwear, dungarees, socks, and overshoes until the stores were empty.

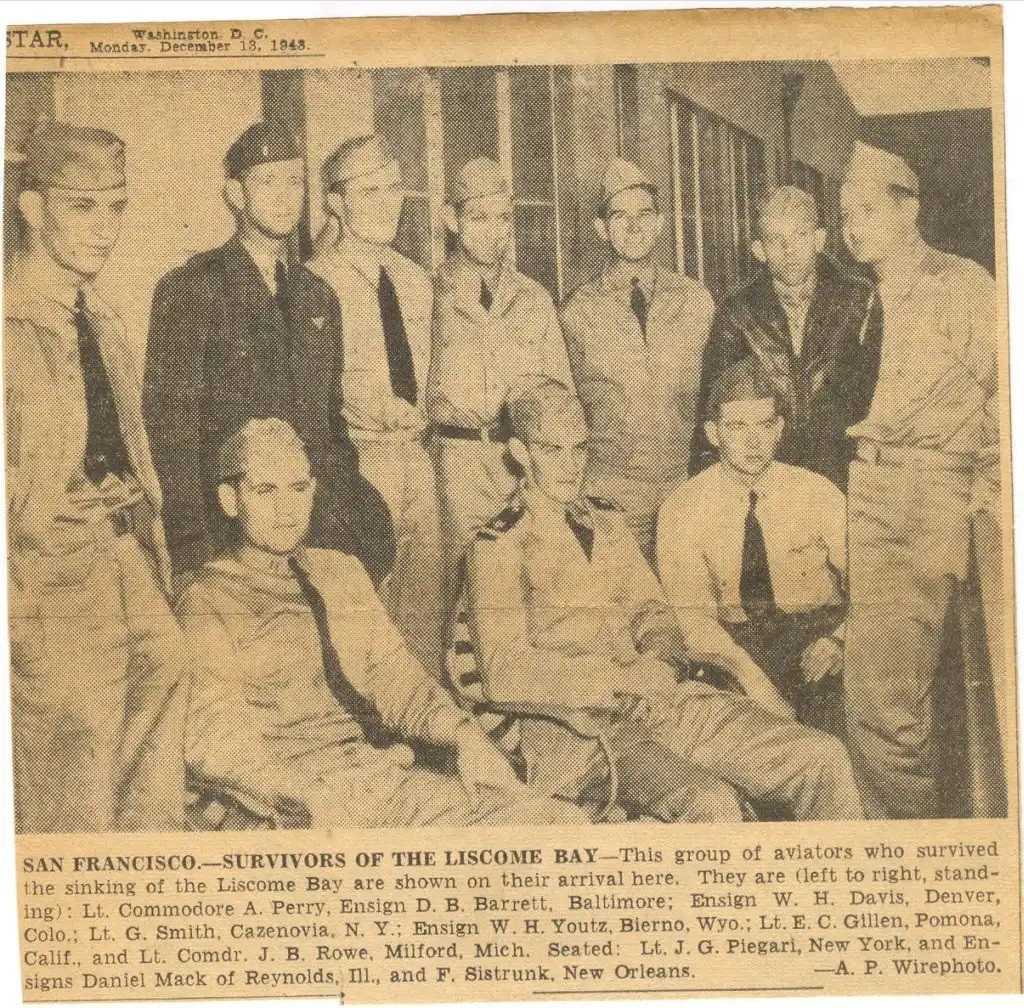

Liscome Bay survivors in San Francisco, CA. Reprinted from The Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 13, 1943, A-2.

Two unidentified enlisted men of Liscome Bay are buried at sea after succumbing to wounds sustained from an enemy torpedo explosion, ca. November 1943 U.S. Navy Photograph 26-G-3182, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, MD.

At midday, survivors transferred to the destroyer MacDonough (DD-351) and the attack transport Leonard Wood (APA-12) bound for Hawai’i where the severely injured could receive trauma care. Rescue operations yielded fifty officers and two hundred and fifteen enlisted men. Among the 683 deceased—and presumed deceased—were Capt. Wiltsie, Rear Adm. Mullinix, and Ck3c Miller.

Representatives from the offices of the Chief of Naval Operations; Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet; Bureau of Aeronautics, Ships, and Ordnance; Commander Fleet Aircraft, West Coast; and the Maritime Commission arranged for interviews of the survivors upon their return to the states. These statements were then used to prepare the final report that determined the cause of the sinking, lessons learned, and suggested improvements for escort carriers. The final report determined “that the primary cause of the loss of the vessel was the mass detonation of aircraft bombs stowed in the hold” between frames 152 and 168 “by a contact torpedo explosion on the starboard side in way of, or very near, this magazine.” The investigation into the sinking determined that the haste required for the construction of escort carriers—or conversion to an escort carrier from merchant C-3 hulls—prohibited redundant damage control systems for thicker bulkheads to protect against exploding ordnance fragments in the torpedo and bomb stowage spaces.

The Pittsburgh Courier reported the death of Dorie Miller, “along with hundreds of other gallant American youths,” on New Year’s Day 1944. Editors lamented that Miller went to his death still a cook. “His gallant sacrifice has failed to lift the shroud of segregation,” the article continued, “which envelopes not only the thinking but actions of the Navy Department.” Correspondence in Miller’s military personnel file, addressed to his parents from the Casualty Branch Head, confirms that the family received word of their son’s status as missing on December 6, 1943. The letter included details describing the final moments of Liscome Bay—that the ship “was struck by one or more torpedoes from an enemy submarine about dawn” and sunk. An unnamed commanding officer of a rescue vessel described the “absolute courage” of the survivors in the water as “electrifying.” Survivors displayed “no visible confusion, for everyone was just plain busy with the job at hand.” On the second anniversary of the sinking, the Bureau of Personnel informed the Millers in a letter that the Navy Department listed the death of Dorie Miller “to have occurred on 25 November 1944, which is the day following the expiration of twelve months in the missing status” in accordance with Section 5 of Public Law 490. Three hundred and sixty-six days after the sinking, all remaining crewmembers listed as unaccounted for, like Miller, were listed as lawfully deceased.

Liscome Bay received one battle star for her World War II service, for her participation in the Gilbert Islands Operation (20-24 November 1943).

Commanding Officer Date Assumed Command

Capt. Irving D. Wiltsie 7 August 1943

Heather M. Haley

13 November 2023