Legacies of Service: A Retrospective of the Navy Surgeon General

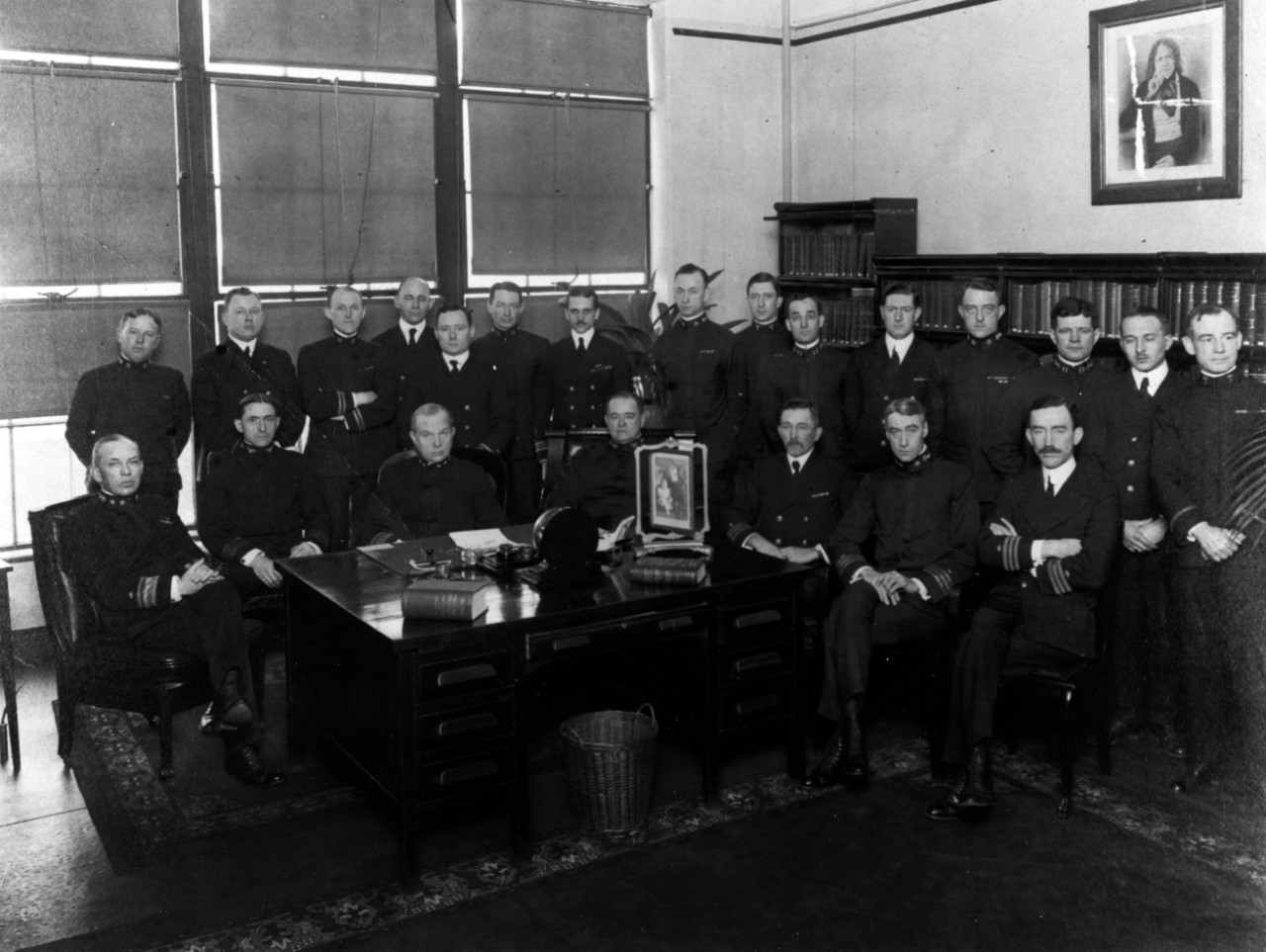

Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, headquarters staff in the Surgeon General’s office, located in the Navy Department or Munitions Building, Washington, D.C., circa 1918-19. Rear Admiral William C. Braisted, the Surgeon General, is seated third from the left. Note the photograph of 19th Century Surgeon General William P.C. Barton on the wall, at right. Collection of Rear Admiral William C. Braisted, USN(MC). Courtesy of Dr. WIlliam R. Braisted. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 91529)

by André B. Sobocinski, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED)

Since 3 March 1871, the Surgeon General of the Navy has stood at the helm of the Navy Medical Department embodying the organization’s mission, vision, and direction. It is hard to think of a Navy Medicine without a surgeon general or a nominal head, but this was exactly the case.

When the U.S. Navy was established in 1798, 24 physicians were granted commissions that year. Although they would represent the beginnings of the Navy Medical Department, none of these trailblazing physicians served in the position as the head of Navy Medicine. In the ensuing decades a host of senior physicians based in Washington, D.C. played a de facto role as consultants to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Naval Commissioners on medical issues, but without a formal title acknowledging this role.

With Congress’s Appropriations Act of 31 August 1842, the Navy’s bureau system was created, which established the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED). Heading the new BUMED was a chief who was responsible for all communications, requisitions, and policy relating to medical affairs of the Navy. However, the chief of BUMED held no formal rank or command until the Appropriations Act of 3 March 1871.

The Appropriations Act recognized Navy physicians as an official staff corps (Medical Corps), standardized relative ranks for medical personnel, and granted the chief of BUMED the additional title of “Surgeon General of the Navy” (with the rank of Commodore). The surgeon general would act as both an administrator and a director of professional medical services in the Navy. On 3 March 1871, BUMED Chief William Maxwell Wood became the first Surgeon General of the Navy.

From that point on Navy Surgeons General focused their attention to building the foundations for the future of Navy Medicine, and helped to advance medical science in the preservation of the health of Sailors and Marines. Principles of naval hygiene and laboratory research were promoted, the first instructions for medical officers and and statistical reports from those serving with the fleet were were published,, and for as long as there has been a Navy Medicine presence there has been a desire to improve the ability of the organization to better serve the warfighter.

Surgeon General Legacies

In the 1890s and 1900s, Surgeons General J. Rufus Tryon, William Van Reypen, and Presley Marion Rixey helped lead Navy Medicine into the twentieth century by pushing for modernization of naval hospitals, adopting new standards for medical care, and expanding the scope of Navy Medicine. Tryon, a long proponent of an enlisted corps of medical-trained Sailors and hospital ships, saw the realization of work in 1898 with the established of the Navy Hospital Corps and the commissioning of USS Solace, the Navy’s first white-hulled hospital ship.

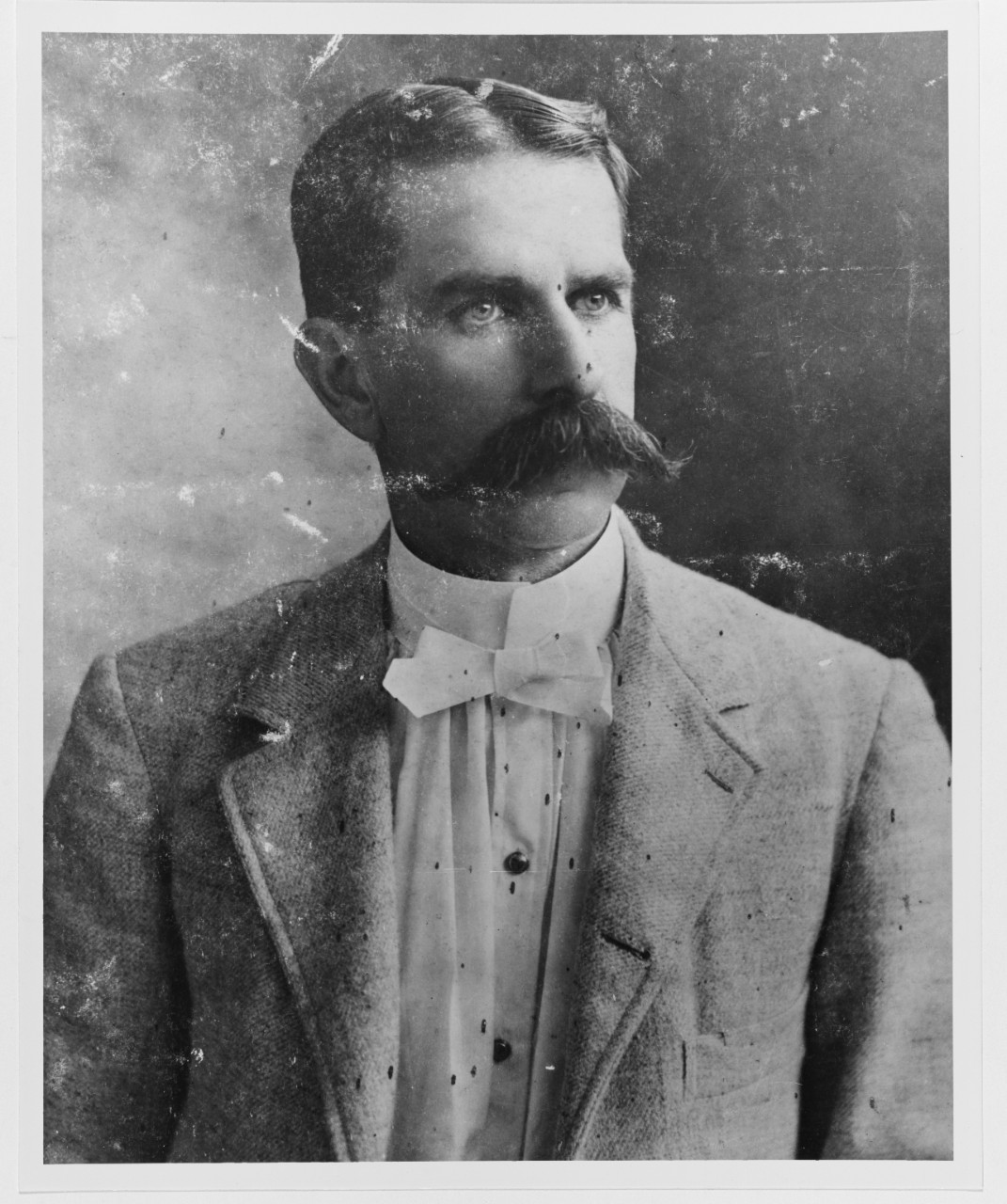

In the early twentieth century, few surgeons general made as big an impact on Navy Medicine as Rear Admiral Presley Marion Rixey. Appointed surgeon general in 1902, Rixey had come to this role after serving as personal physician to President William McKinley and was with the president on that fateful day in 1901 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo when the president was shot. Rixey continued serving as a personal physician to McKinley’s successor, Teddy Roosevelt, and became the President’s personal friend and confidante.

With Roosevelt’s support, Rixey expanded the Medical Department establishing the first specialized infectious disease hospital, the Navy Nurse Corps, a Naval medical school to indoctrinate newly commissioned physicians, a basic training school for new enlisted corpsmen, and he instituted the first physical readiness exams and placed medical officers in command of hospital ships. In 1904, Charles Francis Stokes earned the distinction as the first physician to command a hospital ship when he took the helm of Hospital Ship Relief during its cruise around the world.

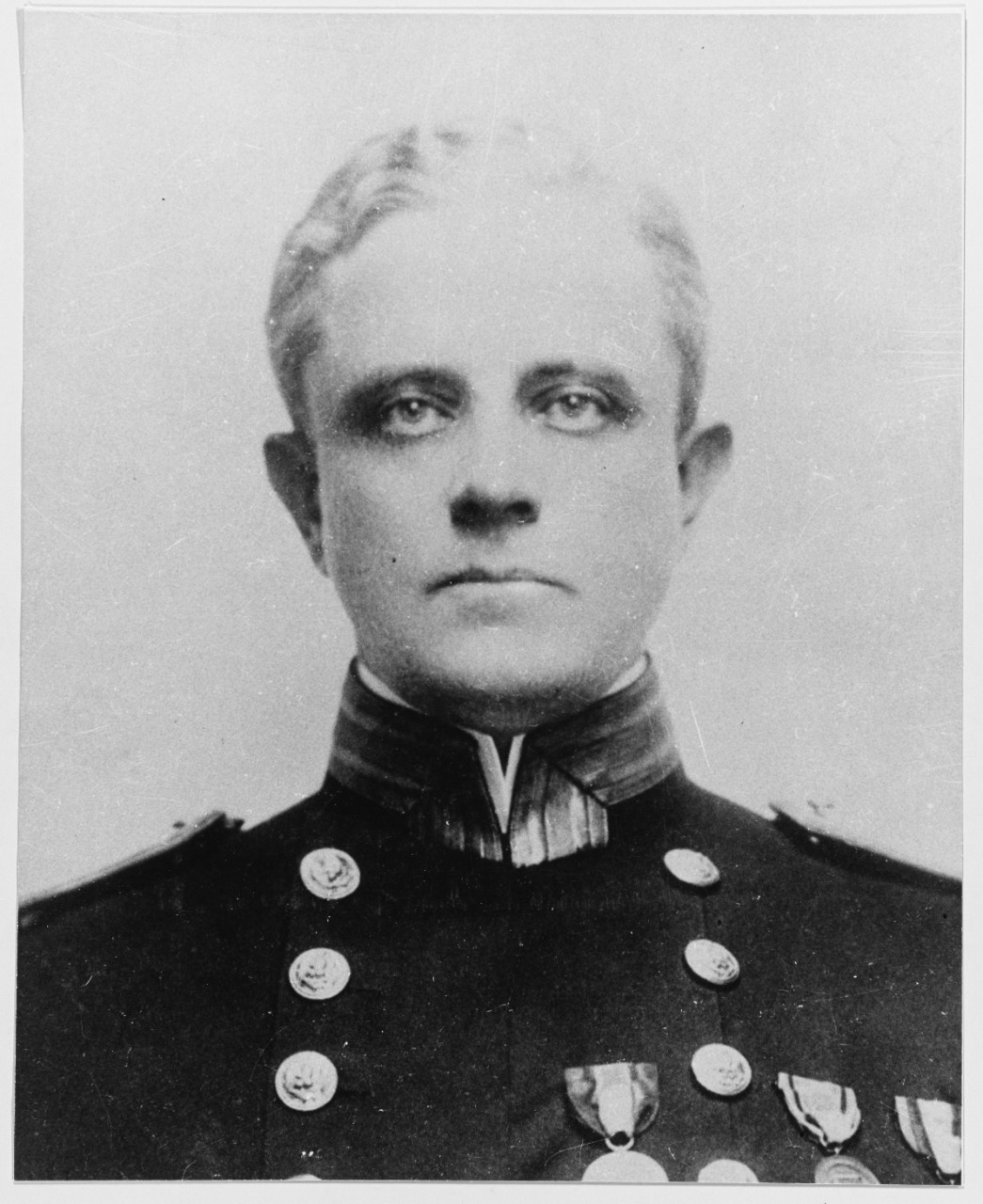

Stokes—also inventor of the wire-basket stretcher that still bears his name—succeeded Rixey as Surgeon General of the Navy in 1910. During his tenure, he oversaw the establishment of the Navy Dental Corps, the inoculation of the fleet and Marine Corps against typhoid, and the issue of athletic injuries at the Naval Academy.

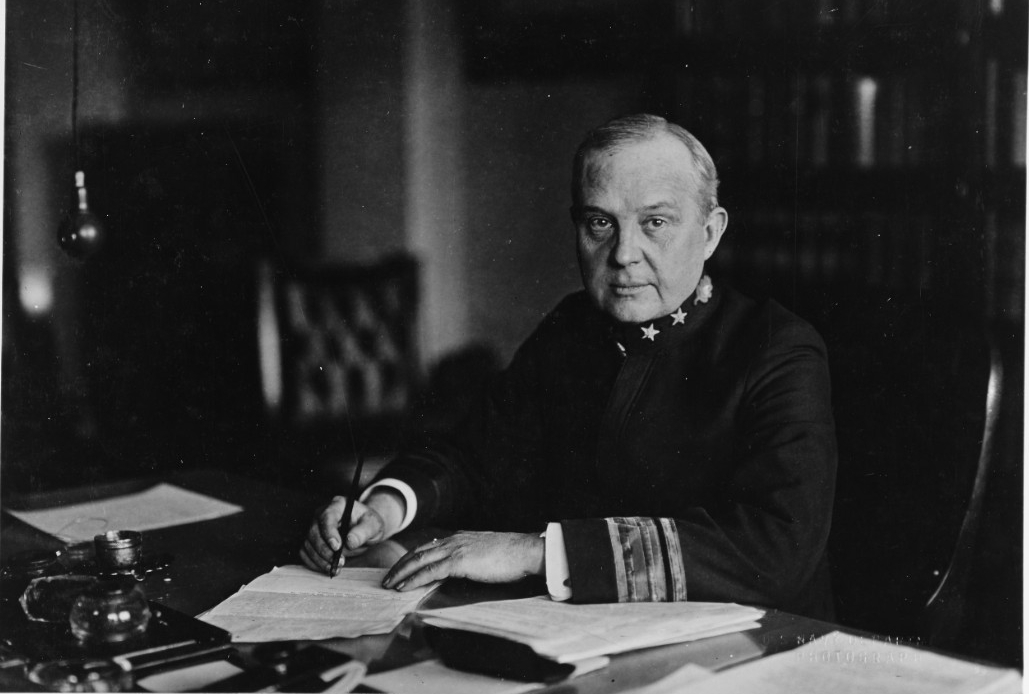

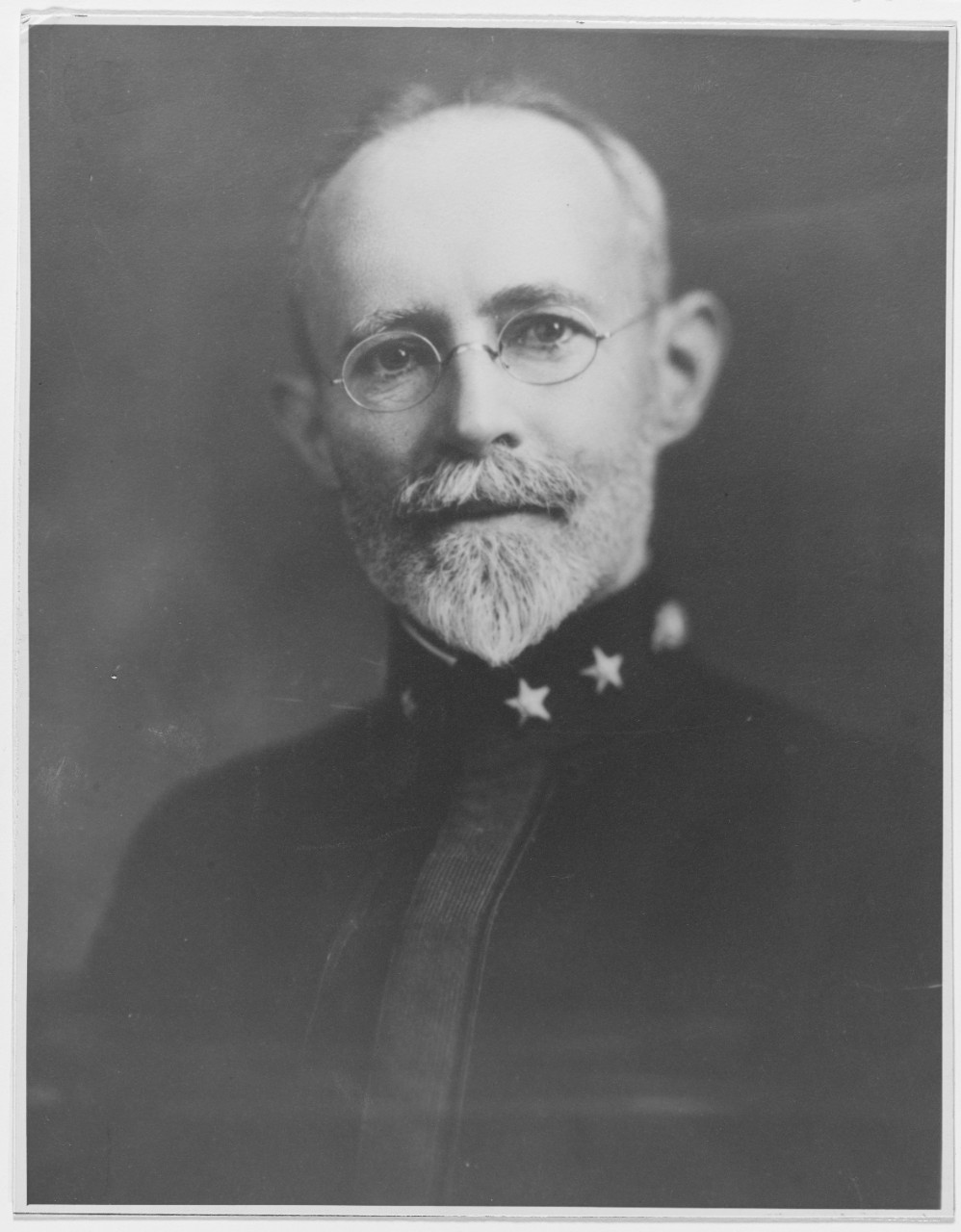

In 1914, William Braisted, a former aide to Presley Rixey, took the helm as Surgeon General of the Navy. Under Braisted, the Navy increased its focus on developing the skills and responsibilities of hospital corpsmen. The Basic Hospital Corps School—which was disestablished under Stokes— had been reestablished in Newport, Rhode Island, followed by other basic corps schools in San Francisco and Great Lakes. BUMED published the first textbook for Hospital Corpsmen, and approved the first formal instruction for Independent Duty Corpsman, as well as some of the first technician schools for enlisted personnel.

During Braisted’s administration, Navy medical personnel deployed with the Marines to Haiti and later to France in the First World War serving on the Western Front, at base hospitals in Europe, aboard combat ships, troop ships, and with aviation groups. As war came to the close, Navy Medicine shifted its focus again on the war against disease.

Endemic diseases that took Sailors and Marines out of the fight has long remained a focus for Navy Medicine. In the first decades of the twentieth century, the Navy Medical School served as the Navy’s arsenal in the fight against disease and educated medical personnel on the latest science on tropical medical, and—during the influenza pandemic—mobilized laboratory and sanitation units—forerunners of the today’s PMUs—to perform a series of public health and preventive medicine duties such as fighting outbreaks of meningitis and influenza. Overseeing much of this was Edward R. Stitt, Navy Medicine’s leading educator and author of textbooks Practical Bacteriology, Hematology, and Animal Parasitology, and Diagnosis and Treatment of Tropical Diseases and was superintendent of the Navy Medical School. In 1920, he was appointed Surgeon General of the Navy.

Under Stitt’s leadership, the Navy expanded its global health engagements, launched USS Relief (AH-1) (the only hospital ship to be built from the keel up as a hospital ship), established the Naval Dental School, and spearheaded new undersea and aviation medical training programs.

Rear Admiral Ross T. Mcintire, USN (MC), taking the Oath as Surgeon General of the Navy for a 2nd term, 1 December 1942. Looking on are: Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, Chief, Bureau of Naval Personnel; Vice Admiral Frederick J. Horne, Vice Chief of Naval Operation; Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet; Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox; Rear Admiral Walter B. Woodson, Navy Judge Advocate; and Rear Admiral Luther Sheldon, Jr., Assistant Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. (NH 47979)

Vice Admiral Ross T. McIntire was a student at the Navy Medical School when Stitt was its superintendent and later reported aboard Relief. In 1938, McIntire was appointed Surgeon General of the Navy. With the outbreak of World War II, Dr. McIntire played a dual role. He had primary responsibility for the health of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, traveling with him on diplomatic missions and military inspection trips. He also presided over the largest Navy Medical Department in history. Vice Admiral McIntire led over 175,000 physicians, dentists, nurses, corpsmen, and Allied scientists in the war effort and oversaw the expansion of Navy Medicine stateside and OCONUS, formation and mobilization of base and fleet hospitals, field medical training, formation of new hospital corps training schools, advent of Navy medical research laboratories and programs, and establishment of naval medical research units.

In World War II, Rear Admiral Clifford Swanson was senior medical officer on the battleship USS Iowa (BB-61). Swanson accompanied President Roosevelt to the Teheran Conference and was with the medical representative with the Congressional committee that inspected the Pacific War area. He became surgeon general in 1946. During his tenure he sponsored legislation that made the Nurse Corps a permanent staff corps and established the Medical Service Corps, formalized entomology and preventive medicine units, and oversaw the advent of dependent medical care, all while managing the largest demobilization in Navy history and the beginning of the Cold War.

Swanson’s deputy surgeon general was H. Lamont Pugh. Pugh had served in the Marine Corps in World War II before pursuing a career in medicine. Appointed Surgeon General of the Navy during the height of the Korean War in 1951, Pugh earned the distinction as the first surgeon general ever to visit an active war zone. He later authored an autobiography, Navy Surgeon, in 1959.

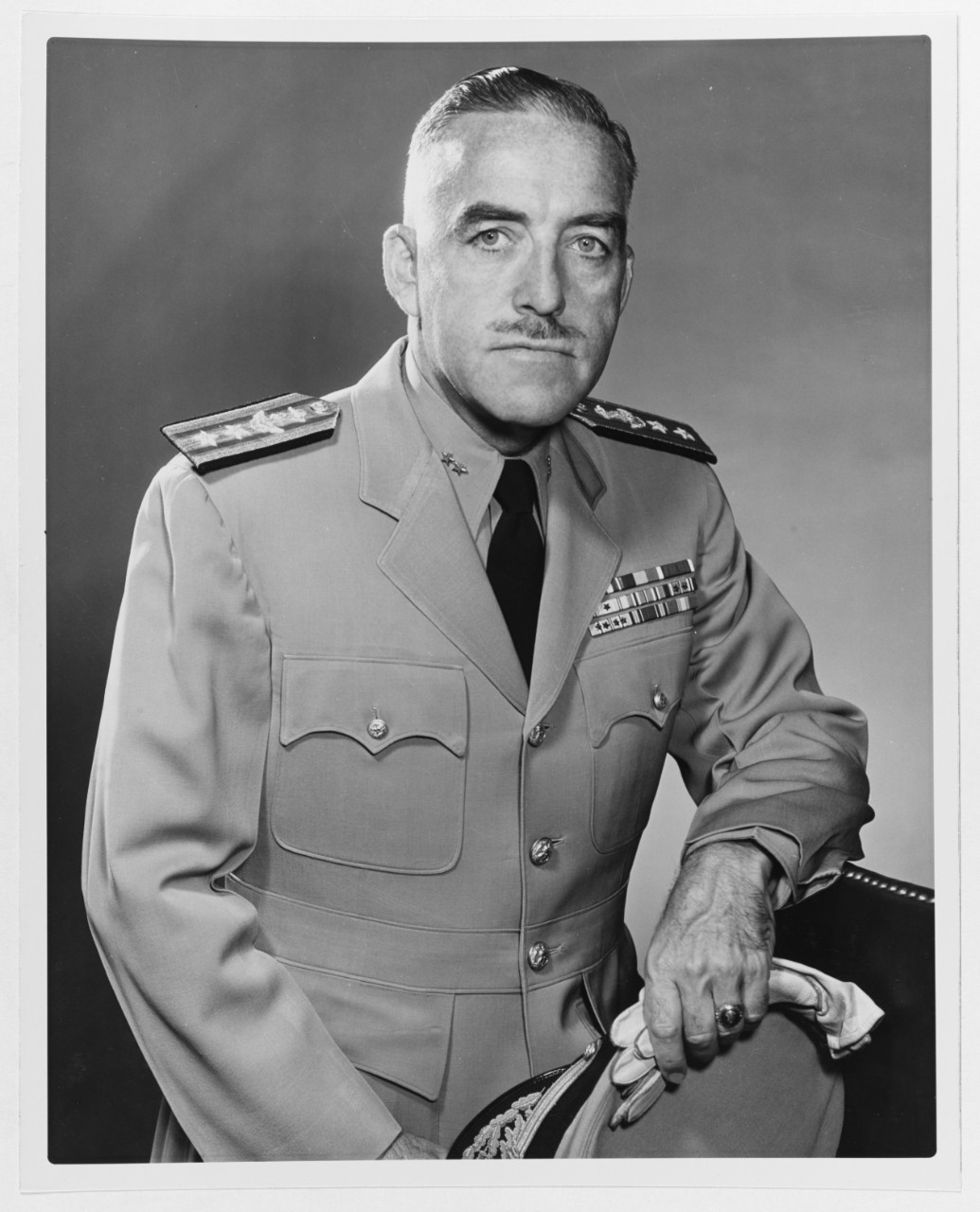

Beginning in 1955, Navy Medicine went through a 21-year span of being headed by a World War II veteran. Among them was Rear Admiral Bartholomew Hogan, who had served as the senior medical officer aboard USS Wasp (CV-7) during the Battle of Midway, and later earned a Silver Star. Appointed Surgeon General in 1955, Hogan was the first psychiatrist serving in this role.

During his tenure, Navy Medicine opened up dependent care program to military dependents and retirees to receive medical care in civilian facilities at government expense or in uniformed services medical facilities on a space-available basis. Navy Medicine under Hogan’s watch became more involved in aerospace and undersea medicine, radiation health, and supported the research efforts so vital to the space race. The Naval Medical Research Unit No. 2 (NAMRU-2) was reestablished and would oversee the pioneering work in treating cholera; the Navy’s Blood Laboratory in Chelsea, Massachussetts, was founded and developed a method for freezing whole blood for long-term storage, proving vital for the Vietnam War on the horizon.

Hogan was succeeded in 1961, by Edward Kenney, a veteran of Guadalcanal and a recipient of a Navy Cross for his actions in the campaign. As surgeon general, Rear Admiral Kenney continued to promote advances in medical research and in submarine, aviation, and preventive medicine. Kenney would help usher in the first anti-tobacco campaign and policies in the Navy.

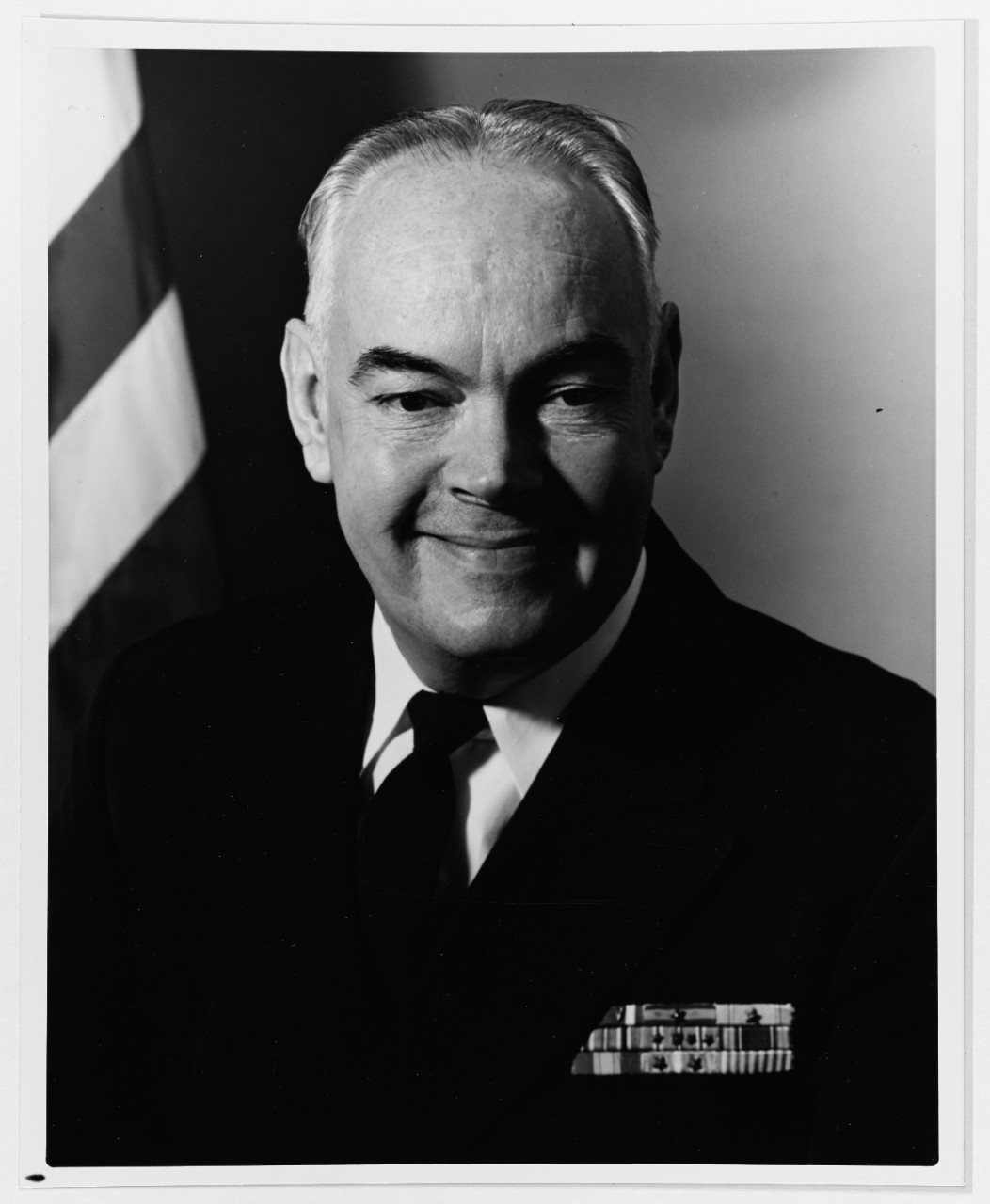

On 2 August 1964, USS Maddox (DD-731) was fired upon by three Vietnamese motorboats in the Gulf of Tonkin. The event led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (10 August) authorizing U.S. retaliation on North Vietnam and marking an “official” beginning of the Vietnam War. Robert Brown was serving as deputy surgeon general as Navy Medicine began focusing on Vietnam. The following year Brown was appointed Surgeon General of the Navy. In October 1965, Brown became the second surgeon general promoted to vice admiral.

As surgeon general, Brown oversaw the medical requirements supporting forces deployed to Vietnam and the deployments of the hospital ships Sanctuary (AH-17) and Repose (AH-16). He also promoted medical research, critical training in critical specialties and combat medicine, and the construction of new and replacement medical facilities in Rota, Spain; Naples, Italy; Cherry Point, N.C.; Lemoore, California; Whidbey Island (Oak Harbor), Washington; Orlando, Florida; Patuxent River, Maryland; Port Hueneme, California; and Taipei, Taiwan.

Vice Admiral George Davis succeeded Brown as Surgeon General of the Navy in 1969. During his term, he managed the Medical Department during the latter stages of the Vietnam War, maintained the department’s support of wartime medical requirements, increased support of health care for family and retirees and began exploring the use of physician assistants. He also obtained flag rank for the Nurse Corps and help create the position of Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Medical Department, the predecessor of today’s Force Master Chief and Director of the Hospital Corps.

In 1973, Vice Admiral Donald Custis became Surgeon General of the Navy as the Navy Medical Department began a postwar drawdown and a year after the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act started the Health Professions Scholarship Program to help recruit medical personnel. During his term, Custis led the Medical Department through postwar downsizing, expanded regionalization of medical and dental facilities, and was a strong proponent of graduate medical education and research.

Custis was followed by Vice Admiral Willard Arentzen, who directed studies on the hospital ship construction project, established BUMED’s Contingency Planning Division, made major improvements in the Navy Medical Department’s training and assignment policies, and continued to organize and support the Navy’s alcohol and substance abuse treatment programs.

Vice Admiral J. William Cox became Surgeon General of the Navy in 1980. During his term, he obtained flag rank approval for the Medical Service Corps, advanced the fleet hospital and hospital ship concepts, oversaw the deactivation of BUMED and the standing up of the Naval Medical Command.

In 1982, submarine medical officer and ophthalmologist Lewis Seaton became the first commander of the Naval Medical Command. The following year, he was appointed the Surgeon General of the Navy and Director of Naval Medicine (The title of Chief of BUMED ceased to exist after BUMED was deactivated). In that office, he oversaw construction and delivery of two new hospital ships, USNS Mercy (T-AH-19) and USNS Comfort (T-AH-20).

Navy Medicine—and the nation—suffered one of its most tragic days on 23 October 1983. A truck bomb detonated outside the First Battalion, Eighth Marines Landing Team Headquarters (1/8 BLT) at the Beirut International Airport. The resulting blast killed 220 Marines, 18 Navy Sailors and three Soldiers. In wake of the tragedy, Rear Admiral James Zimble, a former medical officer of the Marine Corps, authored the seminal work, Medical Readiness Planning in the U.S. European Command. Zimble’s report brought light to the neglect of medical readiness and shortfalls in achieving the mission. Zimble was appointed Surgeon General of the Navy in 1987 and refocused Navy Medicine’s mission to serving the warfighter. Under now Vice Admiral Zimble, Navy Medicine’s motto became, “Standing by to Assist.”

During his term as surgeon general, Dr. Zimble presided over the disestablishment of the Naval Medical Command and the reactivation of BUMED, and managed the first deployment of the hospital ships Mercy and Comfort, fleet hospitals, and medical personnel for the Gulf War.

Appointed Surgeon General of the Navy in 1991, Vice Admiral Donald Hagen’s experience in operational medicine enabled the Navy Medical Department to meet unprecedented demands for operational medical support for peacekeeping, humanitarian missions, and disaster relief. During his tenure, Navy medical personnel were deployed to Zagreb, Croatia; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and aboard the hospital ship Comfort in support of Haitian migrants. Admiral Hagen was instrumental in the implementation of advanced telemedicine throughout Navy Medicine, and was an outspoken advocate of health promotion and disease prevention.

Vice Admiral Harold Koenig succeeded Hagen in 1995. Upon taking the helm, Koenig set out on the goals of taking care to the deckplates, marketing TRICARE, and harnessing technology for the betterment of Navy Medicine. Navy began expanding telemedicine capabilities aboard aircraft carriers and standing up the Frames of Choice program.

Vice Admiral Richard Nelson succeeded Koenig in 1998. During his tenure, Navy Medicine increased focus on Force Health Protection. Nelson also oversaw the deployment of the first clinical professionals (e.g., psychologists and physical therapists) aboard warships.

On 10 August 2001, Vice Admiral Michael Cowan became the 34th Surgeon General of the Navy and Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. Cowan’s efforts as leader of Navy Medicine were focused on reshaping forward deployed units and their resources to make them flexible enough to go on location with warfighters. As surgeon general, Admiral Cowan was known as a strong supporter for more physical fitness programs in DoD school systems, fighting America’s battle with growing child obesity rates. He also helped promote anti-smoking and smokeless tobacco cessation campaigns. Because of his support, Navy health providers focused on preventive medicine measures for Sailors and Marines, ensuring that they are healthy and fit for today’s mission, and tomorrow’s future.

Cowan was surgeon general for one month when the attacks on September 11th occurred, forever impacting Navy Medicine and the nation. One of his first actions as was to change Navy Medicine’s motto, “Standing by to assist” to “Steaming to Assist” and deploy Comfort to New York City to render assistance to the rescue workers.

Succeeding Cowan in 2004, Vice Admiral Donald Arthur played a vital role in the Military Health System’s transformation by improving Force Health Protection methods, enhancing wounded warrior services and advancing initiatives and policies that were vital to the operational readiness of our military forces and the quality of life for their families. Under his leadership, Navy Medicine consistently delivered over 4,000 deployed medical personnel in support of the global war on terror and surged to deploy Mercy in support of 2005 South Asia Tsunami relief efforts.

Vice Admiral Adam Robinson, Jr., was appointed the 36th Surgeon General of the Navy in 2007. During his tenure as surgeon general, he ushered in a new patient and family-centered care model that expertly balanced the dual mission of providing readiness to Sailors and Marines deployed to war zones while maintaining world-class care at home and abroad. Robinson presided over the lowest battlefield mortality rate in history, strengthened global health diplomacy through new military medical partnerships in places like Botswana, Djibouti, and Vietnam, and directed humanitarian relief efforts in Haiti and Japan. His accomplishments earned him the reputation as a leader of national and international prominence in unprecedented times of challenge.

As head of the Navy Medical Department, and Robinson’s immediate successor, Vice Admiral Matthew Nathan stood at the helm during one of the most transformative times in its history—when the economic difficulties of the postwar world combined with the organizational challenges posed by the Unified Medical Command concept. Traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress would remain major issues during Nathan’s tenure as surgeon general. During his administration, the Navy served on the forefront of understanding what traumatic brain injury and traumatic stress does to people and taking on the challenge of treating and dealing with it from a continuity of care standpoint. As surgeon general, Nathan was also a dedicated supporter of humanitarian missions and diplomacy through medicine, ensuring that the hospital ships Mercy and Comfort played significant roles in the Pacific Partnership and Continuing Promise missions.

In December 2015, Admiral Faison was appointed the 38th Surgeon General of the Navy. During his tenure as surgeon general, Faison oversaw the shift in focus from an MTF-based care model to operational readiness. In order to ensure readiness, Faison directed a comprehensive review, rewrite and update of the Hospital Corps “A” School curriculum, placed a Personnel Qualification Standard (PQS) program in hospitals, and established trauma-training agreements with major civilian trauma centers in the United States. His attention to enlisted trauma training helped ensure that corpsmen have the requisite knowledge and skills or casualty response. Faison helped initiate the Global Health Specialist Program (GHSP) in 2017 to ensure Navy medical professionals with global health experience, skills, and training receive certifications to fill key positions across the DoD, as well as interagency and international communities. As part of this initiative, Navy Medicine successfully conducted a trauma collaborative exchange with the government of Vietnam to provide emergency medicine services. The resulting effort further strengthened allied medical trauma capacities and provided Navy medical teams the opportunity to sustain their trauma skills in an unfamiliar and resource constrained environment.

Rear Admiral Bruce Gillingham was appointed the 39th Surgeon General of the Navy on 31 October 2019. His immediate goal as the new leader of Navy Medicine was to ensure an increased focus on supporting the operational forces. The new framework for the mission was the Surgeon General’s “Four Priorities” or “4 P’s”—PEOPLE serving on PLATFORMS and PERFORMING with the purpose of projecting medical POWER for Naval Superiority. Navy Medicine’s motto was changed to “Medical Power for Naval Superiority.”

Months into his tenure, Navy Medicine projected its naval power in the fight against the global COVID-19 pandemic, serving on the frontlines in Baton Rouge, Dallas, New Orleans, New York, Los Angeles, Stamford, in Southwest Texas, and in Guam to mitigate the spread, and provide needed ICU capabilities; and leading pioneering medical studies on disease transmission. These early experiences in the war against this pernicious disease led to establishment of new medical platforms—Acute Care Teams (ACTs) and Rapid Rural Response Teams (RRRTs)—that were deployed to civilian hospitals in Texas and the Navajo Nation (Arizona and New Mexico) to provide medical support in the pandemic.

Whether in the war against an invisible enemy like COVID-19 and other public health threats or strategic military threats from other nations, the Surgeon General of the Navy has—and continues—to serve at Navy Medicine’s helm directing its course and helping to ensure that we meet our healthcare mission in support of our warfighters.

***

Sources:

Arentzen, Willard - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Arthur, Donald - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Braisted, William - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Braisted, William and William H. Bell. The Life Story of Presley Marion Rixey, 1902-1910: Biography and Autobiography. Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1930.

Brown, Robert - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Cowan, Michael. Oral History conducted by A.B. Sobocinski and D.V. Ginn, September 12, 2013. Oral History Collection. BUMED Archives.

Cowan, Michael - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Cox, J. William. Oral History conducted by J.K. Herman, November 19, 1993. Oral History Collection. BUMED Archives.

Cox, J. William - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Custis, Donald - Oral history conducted by J.K. Herman, October 25 and November 19, 1992. Oral History Collection. BUMED Archives.

Custis, Donald - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Faison, C. Forrest. Oral History conducted by A.B. Sobocinski, September 25, 2019. Oral History Collection. BUMED Archives.

Hagen, Donald. Oral history conducted by D.V. Ginn, April 20, 2016. Oral History Collection. BUMED Archives.

Hagen, Donald - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Hogan, Bartholomew - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Langley, Harold. A History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1995.

A Legacy of Service: Navy Surgeon General Retrospective. Produced by BUMED and Naval Medical Leadership & Professional Development Command. February 2021.

Kenney, Edward - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Koenig, Harold. From 4-F to U.S. Navy Surgeon General. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2019.

Koenig, Harold. Oral History conducted by A.B. Sobocinski and D.V. Ginn, September 23, 2015.

McIntire, Ross T. White House Physician. New York, NY: Putnam, 1946.

McIntire, Ross - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Nathan, Matthew. Oral History conducted by A.B. Sobocinski, November 18, 2015. BUMED Archives.

Nelson, Richard - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Rixey, Presley - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Pugh, Lamont - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Robinson, Adam - Oral History conducted by J.K. Herman, October 22, 2012. BUMED Archives.

Seaton, Lewis - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Stitt, Edward - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Swanson, Clifford - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Tryon, J. Rufus - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Van Reypen, William - Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

Zimble, James – Navy Biography. Surgeon General Biography Collection. BUMED Archives.

***

About the Author

André Sobocinski is a native of Norristown, Pennsylvania, who has served as the historian for the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) since May 2012. Mr. Sobocinski is the author of over 250 published works on history and culture including “A History of Naval Hospitals,” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History; “World War I Medicine,” Americans at War: Society, Culture, and the Homefront; and co-author of “History of Navy Medicine,” Medics at War.