William Braisted, the Navy, and the Pandemic of 1918

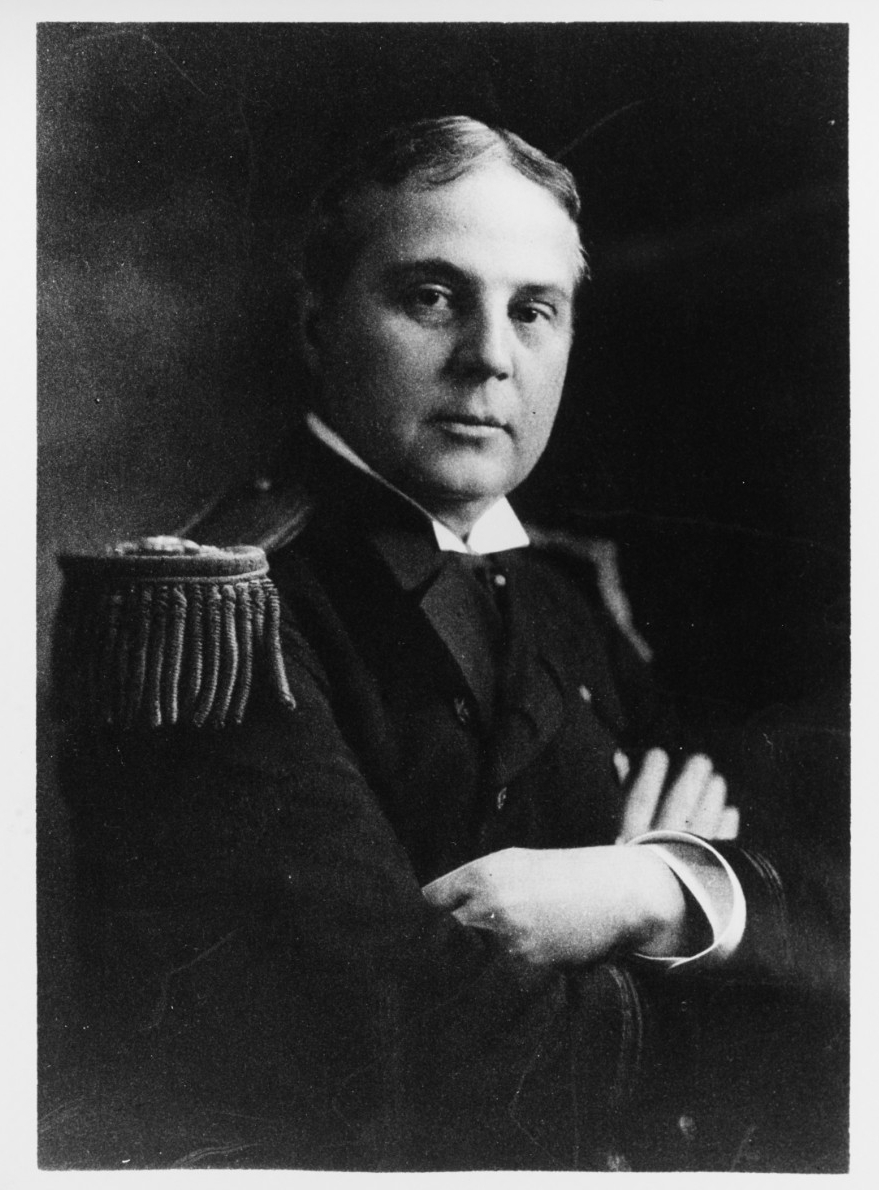

John J. Pershing. William S. Sims. Alvin York. The First World War produced its share of iconic figures for the United States, and helped start the careers of future legends like George C. Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower. Yet back in Washington, others performed less celebrated, but vitally important duties, playing their own crucial role in eventual Allied victory. Few today are likely to recognize the name William Braisted, but as Surgeon General of the Navy during World War I, Braisted was responsible for safeguarding the health of America’s fighting men. His job was enormously complicated by the fact that he had to oversee the Navy’s health during one of the worst pandemics ever to strike the globe. Under his leadership, the Navy was able to keep America’s fighting forces effective despite unprecedented challenges, and thus he made a vital contribution to victory.

Braisted graduated from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1886 and entered the Navy as an assistant surgeon in 1890. His naval career left him well-equipped for the challenges he would face, and he could boast experience as a medical observer in the Russo-Japanese War, attending physician at the White House, and fleet surgeon of the Atlantic Fleet. Woodrow Wilson appointed him Surgeon General of the Navy in February of 1914, and he held the post for the next six years.

The United States’ entry into World War I in April 1917 created an enormous challenge for Braisted. It was the Navy’s job to transport hundreds of thousands (two million by the final count) of Soldiers across the Atlantic to join the war in the trenches. Crowding so many men aboard ships–after they had already been thrown together in close quarters at encampments–made an ideal breeding ground for diseases. Even before the influenza pandemic arrived on the scene, Braisted gave orders for adequate medical quarters at every naval facility to treat and quarantine anyone who showed symptoms of a communicable illness.

Braisted kept a careful eye on the numbers for the normal diseases that the Navy expected to find among crowded groups of men; measles and mumps were the biggest concerns, but meningitis, chicken pox, and scarlet fever also threatened. Then, in the early months of 1918, ominous signs of something new began to appear. An influenza epidemic of unusual severity struck in Haskell County, Kansas, and quickly spread to the nearby Army encampment of Camp Funston. In the fall of 1918, the worst flu pandemic in world history began in earnest. It began with an explosive outbreak at a Navy facility in Boston, where Braisted had already warned the department that men were very dangerously overcrowded and conditions were ripe for disease outbreaks. The first influenza case was reported there on 27 August; two weeks later, there were over 2,000 cases. The disease would go on to claim the lives of over 675,000 Americans in less than a year. The horrifying conditions in some major cities called to mind images of the Medieval Black Death, and in the worst-hit areas it was not uncommon for families to leave their loved one’s body lying out in the street because overwhelmed morgues had too few staff to come and get them.The Navy suffered its full share of the horrors caused by influenza. Crowded conditions on bases were a problem, but the greatest threat was in the troop transports. In the fall of 1918, the Navy was tasked with carrying a quarter of a million men to Europe every month. The battle on the Western Front was reaching its climax, and while the Navy did reduce the number of men on ships, the war refused to wait for the pandemic to pass. Still, Braisted and the rest of the Navy’s leadership did impose strict regulations to contain the spread of the flu. No one displaying symptoms was allowed aboard, and medical personnel were strictly instructed to isolate those whose symptoms appeared after the ship departed. Of course, when the number of patients became overwhelming, keeping them quarantined was nearly impossible, and led to miserable conditions for the suffering, but doctors on troop transports did what they could.

Braisted did not, however, micromanage troop ships to the exclusion of any kind of innovation. The Navy Medical Corps’ Lieutenant W.F. McAnally reported that one naval transport he served on had enjoyed considerable success containing the disease by having the infected use a special medicinal gargle and also injecting them with a “specific bacterin” of the disease. McAnally had to concede that his pool of patients was too small for any definitive conclusions, but he was one of many Navy doctors using trans-Atlantic ships to experiment as well as treat. Likewise on land, the Navy’s physicians labored tirelessly to find some means of treating the plague. At the Naval Hospital in Washington D.C., Navy doctors had remarkable success slowing the death rate by injecting sick patients with a serum made from the blood of those who survived.

Braisted’s Navy was also not content to use only doctors already in the service. Leading figures in American medicine received temporary commissions into the service to research the pandemic and try to develop a cure. Ultimately, no vaccine could be found before the influenza had run its course, but Paul Lewis, one of the leading medical minds in America, did begin the experiments that eventually led to identifying influenza as a virus.

The influenza pandemic ran its course–for the most part–by the spring of 1919. Among the dead were over 4,000 Navy personnel. With over 50 million dead worldwide, some casualties within the Navy were inescapable, but Braisted’s management of the Navy’s medical capabilities during one of the most trying times in the service’s history won him high praise. Dr. Franklin Martin, who served alongside Braisted on the Council of National Defense, commented after the war that working with the Navy’s Surgeon General was “always a joy,” even under the difficult circumstances. “His Bureau of Medicine and Surgery ran along on carefully oiled wheels, and with the details of whose operation, this master steersman was in constant touch,” Martin added, crediting the Navy’s ability to overcome the twin crises of global war and global pandemic to “the vision of [Braisted] and his associates.”

—Thomas Sheppard, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, February 2021

****

Primary Sources:

Braisted to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, 28 May 1917

Braisted Circular Letter, 31 October 1917

Braisted to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, 7 February 1918

Braisted to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniel, 7 September 1918

Braisted to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, 5 November 1918

Naval History and Heritage Command Resources:

“The Most Terrifying Experience: The U.S. Navy and the Pandemic of 1918

Other Resources: