Origins of the Korean War

On 2 September 1945, a Japanese delegation signed an unconditional surrender to the Allied forces aboard Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay, ending World War II. Less than seven months later, there was a drastic decrease in the size of the total active Navy ship force level from 6,768 to 1,248. The fleet in the Pacific was reduced to 158 ships. In June 1950, Missouri was the only U.S. battleship on active duty as war erupted on the Korean peninsula on the other side of the world from her homeport at Norfolk.

The Korean War is often overshadowed by the immensity of World War II and the uncertainty of the Cold War. The conflict in Korea began before the end of World War II, amidst Allied negotiations to end the war with Japan. The Soviet Union, Japan, and China were longtime rivals for control of influence in Korea. After 35 years of Japanese colonial rule, the Soviet Union saw the liberation of Korea as an opportunity to extend their regional influence.

Although the United States was new to this rivalry, President Franklin D. Roosevelt felt that it was necessary to make a plan to avoid communist rule in Korea. In a series of conferences at Cairo and Tehran in 1943 and Yalta and Potsdam in 1945, Allied leaders strategized to ensure their victory and to lay the groundwork for the postwar balance of power. President Roosevelt was the first to introduce the idea of a shared trusteeship of Korea by the Allied powers.

With this promise in hand, Josef Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, agreed to enter the war with Japan within three months of the end of the war in Europe. After the death of President Roosevelt while in office, Vice President Truman became the new President of the United States. Before the final session of the Potsdam conference in July 1945, Truman learned about the first successful test of a new weapon in America’s arsenal: the atomic bomb. He hoped that this weapon might end the war with Japan, forestall the Soviet entry into the war, and moot the promise of a joint trusteeship in Korea. An end to the war with Japan without the aid of the Soviet Union would nullify the promise that Roosevelt had made to Stalin at Yalta. After the Potsdam conference, Truman made the decision to use the atomic bomb to end the war with Japan without the aid of the Soviet Union.

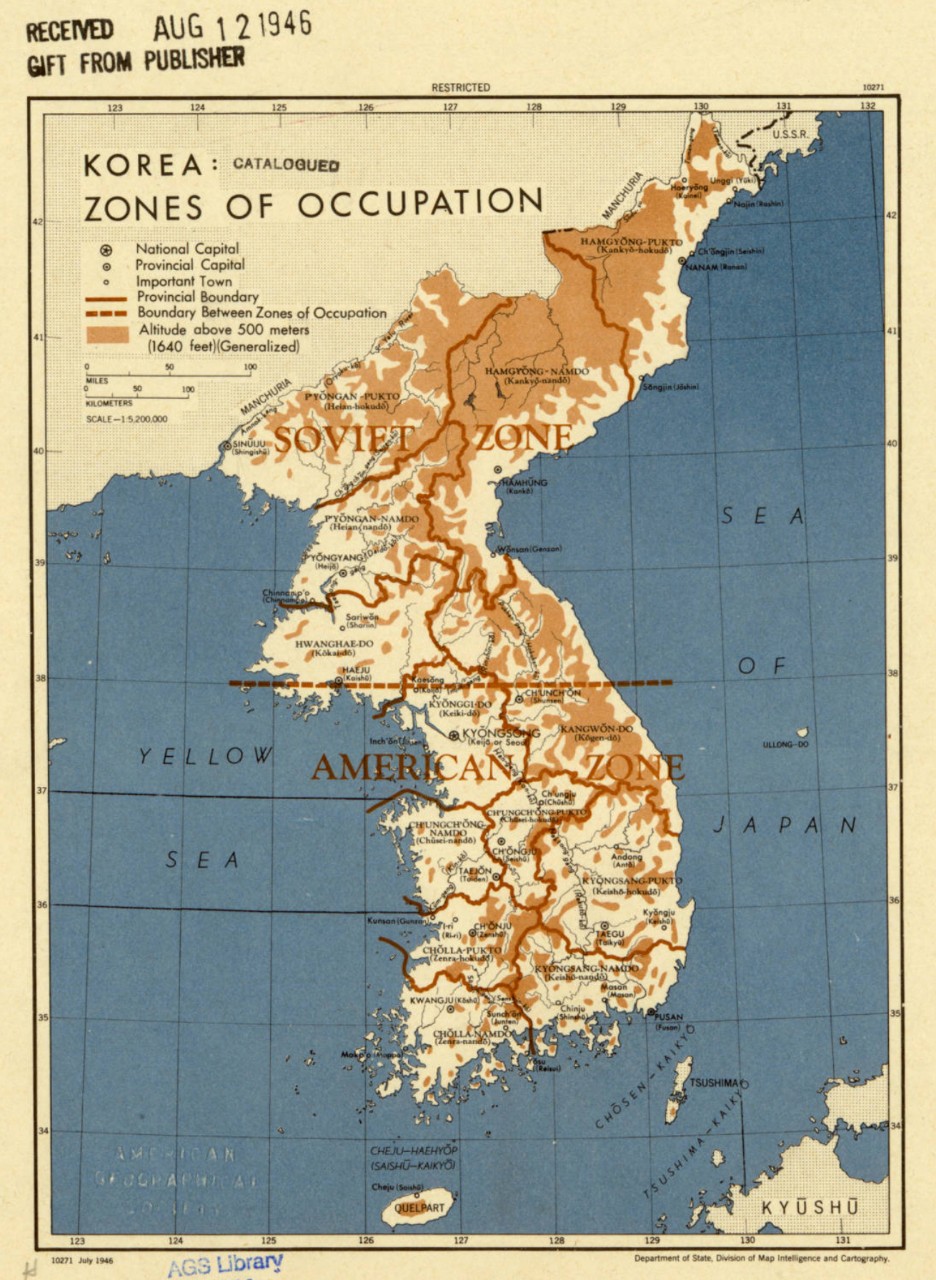

On 6 August 1945, Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. On 8 August 1945, the Soviet Union officially declared war on Japan and marched into Manchuria. Whether it was the impact of the second atomic bomb a day later or the realization that Japan’s neutrality pact with the Soviet Union was at its end, Emperor Hirohito of the Empire of Japan made the decision to surrender to the Allied forces on 10 August 1945. As the Soviet troops marched south, the speed of this sequence of events required even faster action on where to draw the lines for joint trusteeship in Korea. Late in the night on the same day that the Japanese declared their surrender, Colonel Charles H. Bonesteel and Colonel Dean Rusk, both of the U.S. Army, serving in the War Department’s Operations and Plans Division (OPD), hurried to prepare their final recommendation to the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC). Although they consciously kept Seoul, the Korean capital, within the U.S. occupation zone, their line across the 38th parallel divided farms and villages with no consideration for terrain or the local economy. Rusk later clarified that they made this choice “faced with the scarcity of US forces immediately available, and time and space factors, which would make it difficult to reach very far north, before Soviet troops could enter the area.”[1] Their intent was that this line would be temporary and acceptable to the Soviet Union.

Accepting the surrender of the Japanese after World War II was a multi-stage process that required cooperation both within the U.S. military and with its wartime allies. President Truman quickly ordered General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander, Allied Powers, to deploy U.S. forces to Korea and China to protect the new U.S. footholds on the mainland. MacArthur assigned Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, in command of the Navy’s Seventh Fleet, to the task of transporting the XXVI Corps of the U.S. Tenth Army to Korea.

While the formal surrender ceremony was taking place in Tokyo aboard Missouri, Kinkaid and Lieutenant General John Hodge, of the U.S. Army, accepted the surrender of the Japanese forces south of the 38th parallel in Korea at Keijo (Seoul). Following his participation in the surrender ceremony at Seoul, Admiral Kinkaid went on to China, which left the U.S. Army responsible for establishing a temporary military government in the American half of Korea. Hodge stayed on to serve as the military governor of South Korea. The U.S. Army left in Korea continued to rely on components of the Seventh Fleet for transport of repatriated Japanese soldiers.

Between 1945 and 1950, the Seventh Fleet supported the task of repatriating more than 400,000 former Japanese soldiers from China and Korea.[2] Throughout this postwar period, naval leaders observed watched as rising tension over the situation in Korea increased their chances of fighting another war in Asia. The decision to allow the division of Korea in 1945 had been reminiscent of prewar American policy of appeasement. The rise of the communist party in northern Korea was more than symbolic of the truth of Soviet ambitions. Appeasement in establishing the 38th parallel forged a path to further aggression in Korea amidst the early days of an undeclared war between the Soviet Union and the United States.

The impact of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 went beyond the loss of human life. Nuclear weapons represented a marvel in technological innovation, but they also represented a threat and a challenge to other nations. The Soviet Union soon rose to the challenge. On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union completed their first test of an atomic bomb. American scientists detected the seismic activity and high levels of radiation in the atmosphere. Less than a month later, President Harry S. Truman made the decision to share this knowledge with the world. This test confirmed the impending end to the American monopoly on the atomic bomb. With this new intelligence, the risk of an all-out war with nuclear weapons between the United States and the Soviet Union was real. Less than a year later, the conflict in Korea would become the first armed proxy war between the only two countries in the world armed with nuclear weapons.

The origins of a war cannot be attributed to a single act in history, nor is the first confrontation on the field of battle always the first act of war. However, the official version of events typically denotes a single military action as the pivot upon which the opponent responds to the instigator. On June 25, 1950, the official instigator Kim Il-sung, of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The trigger point that preceded his decision to attack is all guesswork. Regardless of the impetus for the first act of violence, it offered an opportunity to the United States and its allies to enforce a new policy of containment in Asia.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

____________

[1] U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, Volume VI, The British Commonwealth, The Far East (Washington, DC: GPO, 1969), Document 771.

[2] Edward D. Marolda, Ready Seapower: A History of the U.S. Seventh Fleet (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2012), 13.

NHHC Resources:

A Time of Change: National Strategy in the Early Postwar Era

- Independence and Responsibility: The Air Force in the Postwar World - Mr. Herman S. Wolk

- The Influence of Naval Strategy On National Security Planning, 1945-1955 - Dr. Michael A. Palmer

- Forces and Strategy: The Air Force and the Strategic Mission, 1945-1950 - Dr. Walton S. Moody

- The Navy and the Bomb: Naval Aviation's Influence on Strategic Thinking, 1945-1950 - Dr. Jeffrey G. Barlow

United States Naval History, A Bibliography—Postwar Years, 1946-1991

Further Reading:

Davis, Vincent. Postwar defense policy and the United States Navy, 1943-1946. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966.

Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941-1947. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Marolda, Edward J. Marolda, “Asian Warm-up to the Cold War.” Naval History 25, no. 5 (October 2011): 26–32.

Palmer, Michael A. Command at Sea: Naval Command and Control since the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Sokolsky, Joel J. Seapower in the Nuclear Age: The United States Navy and NATO 1949-80. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 1991.

Stoler, Mark A. Allies and Adversaries: the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Grand Alliance, and US Strategy in World War II. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Wheeler, Gerald E. Kinkaid of the Seventh Fleet: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, U.S. Navy. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1996.