Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

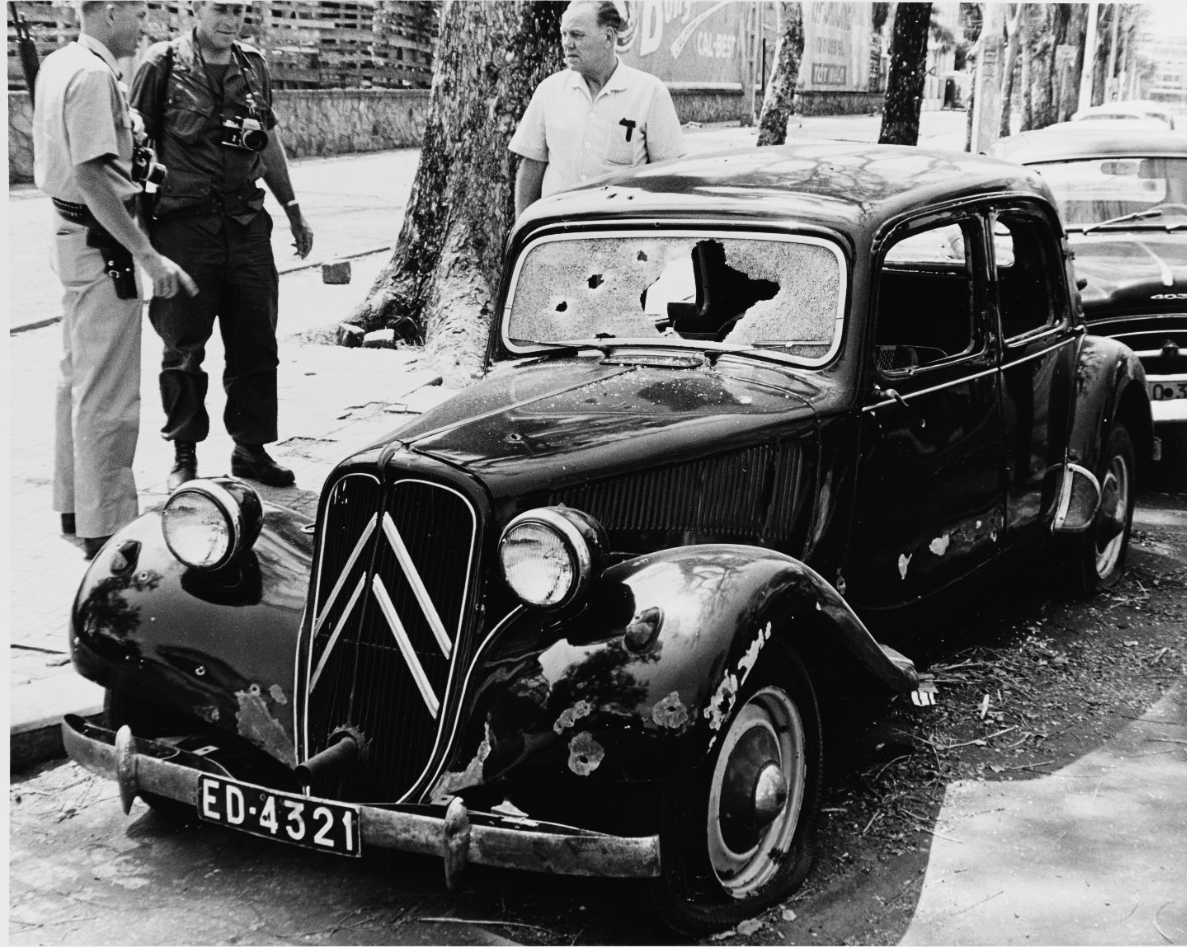

Tet Offensive Begins

In the early hours of Jan. 30–31, 1968, during Vietnam’s Lunar New Year celebrations (Tet), the enemy-led Tet Offensive began when some 85,000 North Vietnamese government troops and Viet Cong guerrillas simultaneously attacked major cities, dozens of military installations, and scores of towns and villages throughout South Vietnam (estimated to be more than 150 South Vietnamese targets). It was arguably the turning point in the Vietnam War. The massive assault was an attempt to incite an uprising among the South Vietnamese populace and break the stalemate between North Vietnam and American-backed South Vietnamese forces that had been going on for years. The offensive ultimately was a crushing tactical defeat for the North Vietnamese and especially for the Viet Cong, which used conventional tactics that were effectively countered by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces and suffered heavy losses. However, the media extensively publicized the impact of the attack, thereby striking a sharp psychological blow to American public and political support for the war. Although enemy casualties were estimated to be around 45,000–58,000 killed, including losses during the “mini-Tets” that occurred over the next eight months, the Tet Offensive turned out to be a massive psychological, propaganda, and strategic victory for North Vietnam. Ultimately, it soured the will of the United States to sustain the war.

In the months preceding the Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) engaged in extensive intelligence deception operations that were designed to focus allied attention to the border areas of the country and away from coastal cities. In hindsight, NVA operations at Con Tien and Dak To in the central highlands made little military sense and cost the NVA heavily, but they succeeded in the deception objective. Although U.S. commanders viewed the enemy attacks on the Khe Sanh operating base as an attempt by North Vietnam to replicate its unprecedented victory against the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the real NVA objective was to tie down a large number of allied forces and divert attention away from preparations for the Tet Offensive. The North Vietnamese government also announced that it would honor a truce between Jan. 27 and Feb. 3 in conjunction with Tet, something that they actually had no intention of upholding. Allied forces accepted the stand-down and a large amount of military personnel (mostly South Vietnamese) were on leave when the offensive commenced. Although several premature Viet Cong attacks already occurred on Jan. 29, allied forces were unable to recall troops in a timely matter and were ill-prepared.

Despite the North Vietnamese element of surprise and the initially low numbers of South Vietnamese troops available, the enemy attacks were beaten back in just a matter of days, with the exception of the old Vietnamese imperial capital of Hue, where two NVA battalions succeeded in occupying the city’s citadel. It wasn’t until Feb. 25, when the South Vietnamese Army and U.S. Marines recaptured Hue at the cost of 216 U.S. Marines killed and 1,600 wounded (Aegis-class cruiser USS Hue City (CG-66) was named in commemoration of the fight to recapture the city, the only U.S. Navy ship named after a Vietnam War battle).

As part of the Tet Offensive, Viet Cong forces attacked most of the cities along the Mekong River Delta, a strategically vital area of South Vietnam. The Navy’s riverine forces played a critical role in the rapid movement of U.S. Army Soldiers to repulse the enemy from every city they attempted to occupy. In several cases, U.S. Navy SEALs (Sea, Air, Land) from five detachments transported by Navy riverine craft, drove off the Viet Cong. In addition, the North Vietnamese attempted to surge supplies into South Vietnam via trawlers and other smaller, inconspicuous-looking vessels. U.S. Navy ships operating as part of Operation Sea Dragon (the bombardment of the North Vietnam coast) interdicted some of the traffic. Most of the seaborne traffic was interdicted by Task Force 115 (TF-115), the coastal surveillance force executing Operation Market Time. Market Time was mostly a U.S. Navy operation with significant U.S. Coast Guard participation using patrol aircraft and smaller vessels, such as PCF “Swift” boats, to track vessels as they went far into the South China Sea before making a run for the South Vietnamese coast to drop off supplies for the Viet Cong. As much as 90 percent of Communist seaborne resupply and infiltration was estimated to have been interdicted as a result of Market Time. U.S. Navy destroyers also conducted naval gunfire support to U.S. Marine and Army operations along the coastline during the Tet Offensive.

In the end, with the exception of the Battle of Hue and the siege of Khe Sanh, most of the enemy forces were quickly forced back. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong paid dearly for their deviation from a guerilla warfare strategy. The Tet Offensive also created more rejection among the South Vietnamese for the North Vietnam cause.

For more on the Vietnam War, NHHC’s Hampton Roads Naval Museum has a comprehensive display that explores the missions and contributions of the U.S. Navy at sea, on land, and in the skies over Vietnam. It can be viewed online or at the museum’s Virginia location.

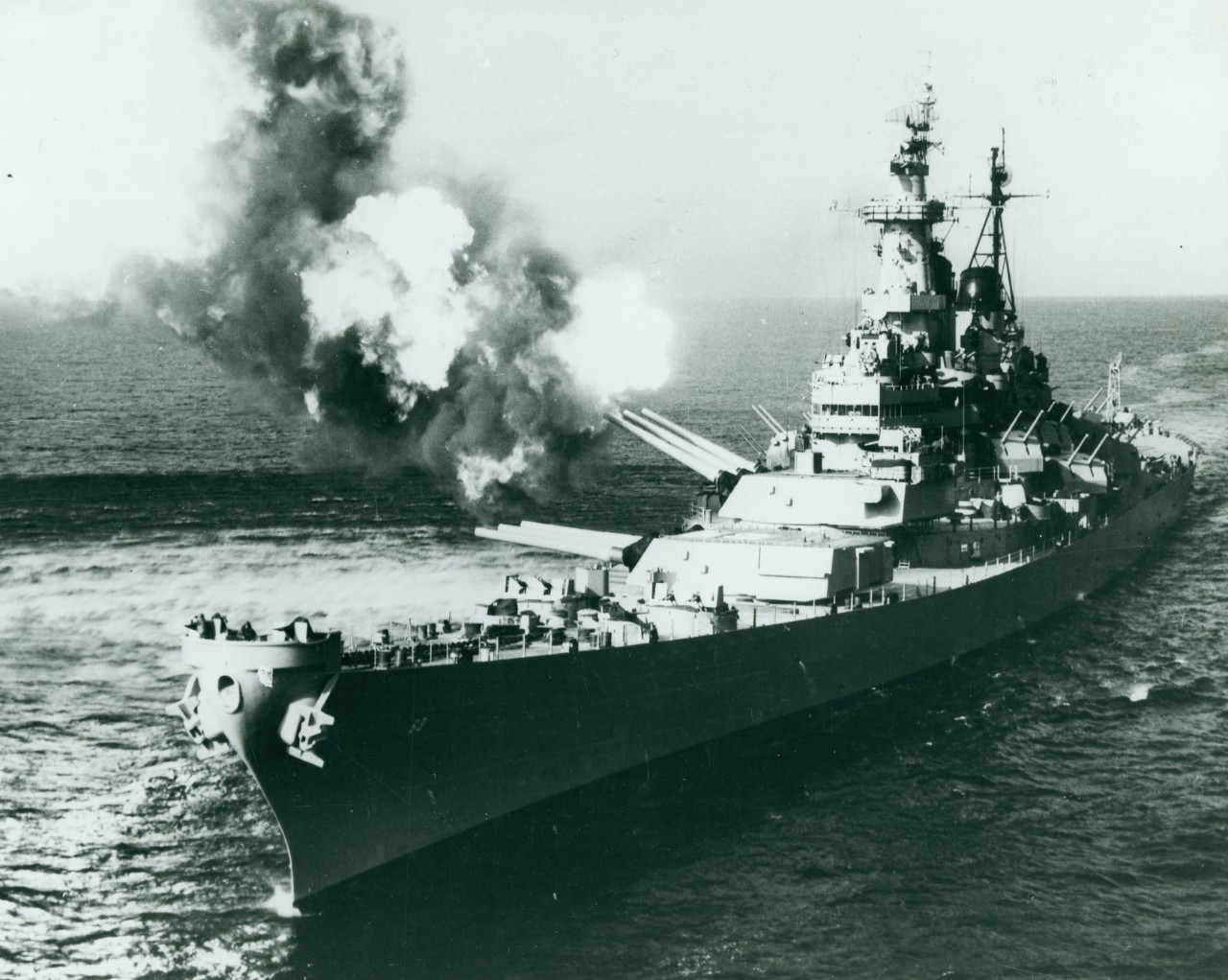

Missouri (America’s Last Battleship) Christened, Launched

On Jan. 29, 1944, the battleship USS Missouri (BB-63) was christened and launched at the New York Navy Yard. Later that same year, on June 11, the ship was commissioned. It was the last battleship to enter active service in the U.S. Navy. After trials off New York and shakedown and battle practice in the Chesapeake Bay, Missouri departed Norfolk, Virginia, on Nov. 11, 1944; transited the Panama Canal; and steamed to San Francisco for final fitting-out as a fleet flagship. After temporarily serving as a flagship for Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher at Ulithi, Western Caroline Islands, Missouri steamed with two aircraft carriers to participate in the Battle of Iwo Jima. The battleship’s 16-inch guns provided direct and continuous support for the invasion of the tiny volcanic island, which began on Feb. 19, 1945. On March 5, Missouri returned to Ulithi and was assigned to the USS Yorktown (CV-10) carrier task group. About 10 days later, the task group steamed for the Japanese mainland to strike targets on the coast. After a few days of intense fighting, Missouri made way for pre-invasion strikes and bombardment on Okinawa. After three months of continuous operations in support of the Battle of Okinawa, Missouri retired to Leyte.

About a month later, Missouri prepared to lead Third Fleet in strikes on Japan from within its home waters. On July 8, the task force headed north to approach Japanese mainland. The raids took Tokyo by complete surprise and were followed by more coastal devastation at the juncture of Honshu and Hokkaido on July 13–14. For the first time, a naval gunfire force destroyed a major installation within Japan when Missouri joined in a bombardment on July 15 that damaged the Nihon Steel Co. and the Wanishi Ironworks at Muroran, Hokkaido. During the night of July 17–18, Missouri bombarded industrial targets in the Hichiti area, Honshu. Aerial strikes continued through July 25, and Missouri escorted the carriers as they struck hard blows on the Japanese capital. Strikes on Hokkaido and northern Honshu resumed on Aug. 9, the day the second atomic bomb was dropped. The following day, word was received that the Japanese were ready to surrender provided that the Emperor of Japan’s prerogatives as a sovereign ruler were not compromised. Finally, on Aug. 15, President Harry S. Truman announced Japan's acceptance of unconditional surrender.

On Sept. 2, high-ranking military Allied officials came onboard Missouri, including Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Shortly thereafter, Japanese representatives, headed by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru, arrived. At 9:02 a.m., MacArthur stepped before a battery of microphones and the 23-minute surrender ceremony was broadcast to the waiting world. By 9:30 a.m., the Japanese emissaries had departed the ship. World War II was finally over.

For the next several years, Missouri participated in a number of exercises, cruises, and overhauls. Operations and show- of-force exercises were dominated by the advent of the Cold War. On April 9, 1946, Missouri departed Istanbul for Phaleron Bay, Piraeus, Greece, and the following day received an overwhelming welcome by Greek government officials. The ship had arrived in a year when there were ominous Soviet activities in the entire Balkan area. Greece had become the scene of a communist-inspired civil war as Russia sought every possible extension of Soviet influence throughout the Mediterranean region. Demands were made that Turkey grant the Soviets a navy base in the Dodecanese Islands and joint control of the Turkish Straits leading from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean. The voyage of Missouri to the eastern Mediterranean gave comfort to both Greece and Turkey. News media proclaimed Missouri was a symbol of U.S. interest in preserving Greek and Turkish liberty. With an August 1946 decision to deploy a strong fleet to the Mediterranean, it became obvious that the United States intended to use its naval sea and air power to stand firm against the tide of Soviet dominance.

The threat of the spread of communism came to a head when North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, beginning the Korean War. On Aug. 19, Missouri departed Norfolk, Virginia, to support United Nations forces on the Korean Peninsula. On Sept. 15, as the first American battleship to reach Korean waters, Missouri bombarded Samchok in a diversionary move coordinated with the Inchon landings. In company with heavy cruiser USS Helena (CA-75) and two destroyers, Missouri helped prepare the way for the 8th Army offensive. Later, Missouri conducted bombardment missions in the Chonjin and Tanchon areas, and at Wonsan. The ship conducted additional operations with carriers and systematic shore bombardments off the east coast of Korea until March 19, 1951. Missouri arrived at Yokosuka, Japan, on March 24, and four days later was relieved of duty in the Far East. The ship was back at Norfolk the following month. While at Norfolk, Missouri underwent an overhaul that lasted until January 1952.

In late 1952, Missouri returned to operations off the Korean coast with its primary mission to provide seagoing artillery support by bombarding enemy targets in the Chaho Tanchon area; at Chongjin, in the Tanchon Sonjin area; and at Chaho, Wonsan, Hamhung, and Hungnam. In January and February 1953, Missouri resumed patrols along the east coast of Korea in direct support of troops ashore. Repeated strikes against Wonsan, Tanchon, Hungnam, and Kojo destroyed main supply routes along Korea’s eastern seaboard. Missouri was relieved in April by USS New Jersey (BB-62). Missouri was decommissioned on Feb. 26, 1955, and remained in reserve for the next 30 years.

As the Cold War continued into the 1980s, Missouri received a new lease on life and was modernized and recommissioned at San Francisco on May 10, 1986. Activated as part of the Navy's new maritime strategy that was intended to send offensive aircraft carrier and battleship task groups into Soviet waters in the event of a future global conflict, Missouri conducted refresher and fleet operations training until departing Sept. 10 for a circumnavigation of the world. It was the first such voyage by an American battleship since the Great White Fleet of 1907–09.

After several years of routine exercises and upkeep, news came that Iraqi Dictator Saddam Hussein's army had invaded Kuwait in August 1990. The battleship's crew conducted security drills, installed more point defense weapons, and began preparations for a Persian Gulf deployment. During subsequent operations leading up to Operation Desert Storm, Missouri prepared to launch Tomahawk missiles and provide on-call naval gunfire support. Missouri fired its first Tomahawk missile at Iraqi targets at 1:40 a.m. on Jan. 17, followed by 27 additional missiles over the next five days. In addition, the battleship bombarded Iraqi beach defenses in occupied Kuwait on the night of Feb. 3. Missouri then fired another 60 rounds off Khafji on Feb. 11–12 before steaming north to the vicinity of Faylaka Island. After minesweepers cleared a lane through Iraqi defenses, Missouri fired 133 rounds during four shore bombardment missions as part of the decoy simulated amphibious landings on the Kuwaiti shoreline the morning of Feb. 23. For the remainder of Desert Storm, Missouri conducted patrol and armistice enforcement operations in the northern Persian Gulf until heading for home.

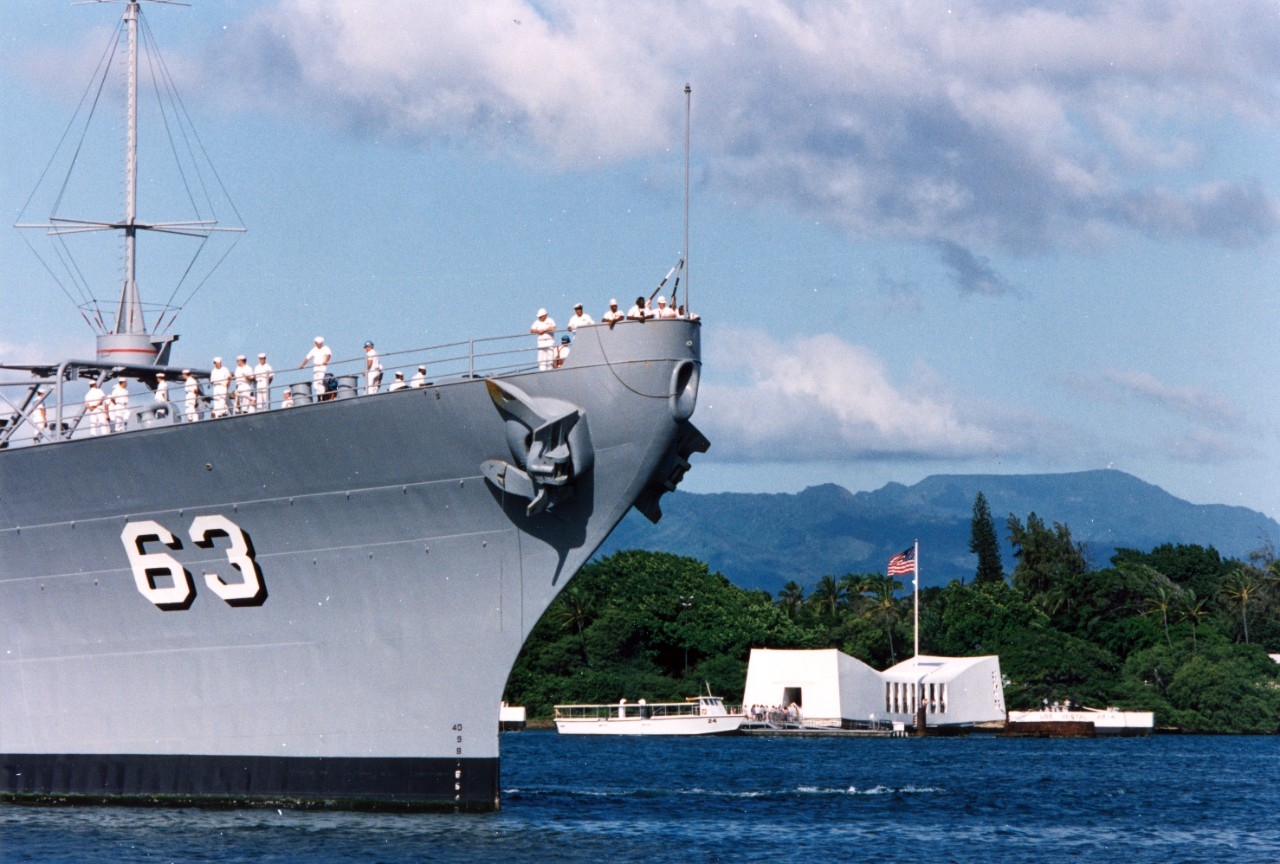

After making way for Long Beach, California, in December 1991, the battleship's crew began the long process of deactivating the ship. Missouri was decommissioned on March 31, 1992 and was laid up as part of the inactive fleet at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington. The ship remained part of the reserve fleet until Jan. 12, 1995. Donated as a museum and memorial ship on May 4, 1998, Missouri was later transferred to Pearl Harbor, where the battleship rests near the USS Arizona (BB-39) Memorial and is open for tours by the public.

Today in Naval History

On Jan. 24, 1991, during the first week of Operation Desert Storm, SEAL (Sea, Air, Land) platoons from USS Leftwich (DD-984) and USS Nicholas (FFG-47) recaptured the island of Jazirat Qurah. It was the first Iraqi-occupied Kuwait territory to be liberated by coalition forces.

When the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait on Aug. 2, 1990, the United States deployed a major joint force as part of a multination coalition to stop President Saddam Hussein’s aggression against his southern neighbor. The U.S. Navy provided sea control and maritime superiority, which paved the way for the introduction of U.S. and allied air and ground forces.

At the time of the invasion, the Navy was already on station in the region. The ships of Joint Task Force Middle East were immediately placed on alert. Battle groups led by USS Independence (CV-62) and USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) sped from the Indian Ocean and eastern Mediterranean to take up positions in the Gulf of Oman and Red Sea, at the ready to commence sustained combat operations.

When President George H. W. Bush ordered the deployment of troops and equipment to defend Saudi Arabia, more than 240 ships carrying about 18.3 million pounds of equipment and supplies were employed. United Nations trade sanctions were immediately imposed against Iraq to undermine the country’s economy. When U.S. Marines began arriving in Saudi Arabia, their supplies and equipment were in close proximity due to existent low-key military ties with friendly Arab states. More than 21,000 naval reservists were called to active duty in support of Desert Shield/Desert Storm.

Hussein's repeated refusal to abandon Kuwait led to the commencement of combat operations on Jan. 17, 1991. The subsequent bombardment by air assets and the effects of the economic embargo decimated Iraq's military infrastructure and morale, degraded communications and logistics, and devastated weapons arsenals. At the beginning of the war, Navy ships launched salvos of Tomahawk cruise missiles against military targets in Iraq to “soften up” the battlefield for ground troops.

After the 38-day air campaign, ground troops began sweeping through Kuwait in blitzkrieg fashion. In a mere 100 hours, the Iraqi army was crushed. Iraqi soldiers surrendered by the thousands. Kuwait was free again.