Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On Sept. 20, 1986, USS Bunker Hill (CG-52) was commissioned at the Charlestown Naval Shipyard in Boston. The Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruiser is the second to be named after the American Revolution battle. Commonly referred to as the “Battle of Bunker Hill,” the British defeated the inexperienced colonials for control of the hills surrounding Boston. Despite their loss, the Americans inflicted significant casualties on the British army, and provided a confidence boost in the early stages of the war. The first U.S. Navy ship named for the June 16, 1775, battle was an aircraft carrier that served more than 20 years, beginning when it was commissioned on May 25, 1943. During World War II, Bunker Hill (CV-17) received the Presidential Unit Citation and earned 11 battle stars for its gallant service. It participated in notable battles such as the Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

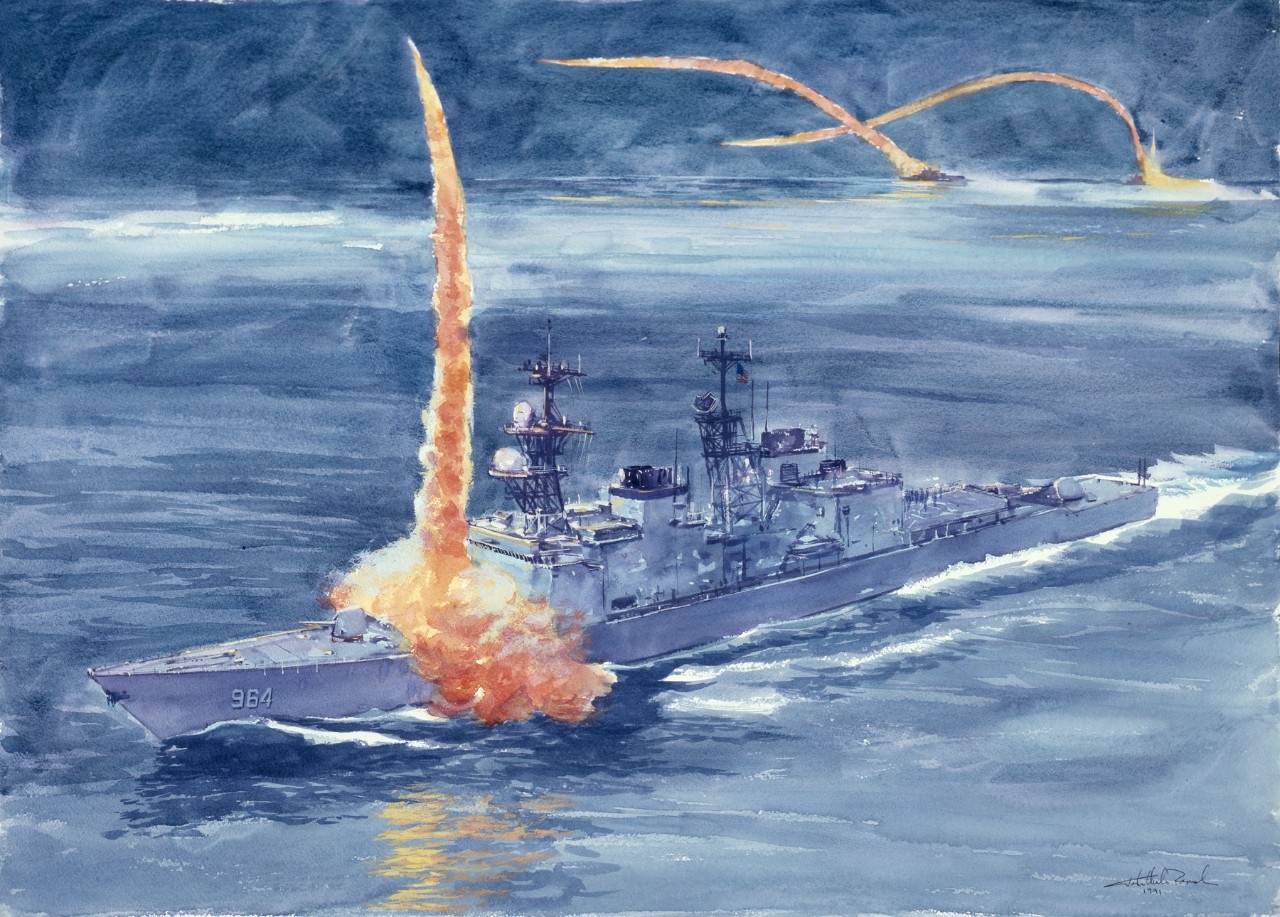

The current Bunker Hill was the first Ticonderoga-class cruiser to be equipped the Mark 41 Vertical Launching System, which greatly improved flexibility and firepower by allowing the class of ships to fire Tomahawk missiles. After commissioning, Bunker Hill was sent to the Pacific to join Seventh Fleet. During its first deployment in July 1987, the ship provided an anti-air warfare umbrella in the Persian Gulf for USS Missouri (BB-63) and other ships transiting through the Strait of Hormuz. In August 1988, Bunker Hill shifted homeports from San Diego to Yokosuka, Japan. During that time, it joined other Seventh Fleet ships again for a four-month deployment, in which it was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation and its first Battle Efficiency (“E”) Award. In November 1990, Bunker Hill steamed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm. During the operation, Bunker Hill served as the multinational Air Warfare Commander and was one of the first ships to launch Tomahawk missiles at Iraqi targets.

Following the Gulf War, Bunker Hill participated in organizing and establishing Operation Southern Watch—the enforcement of the United Nations no-fly zone over southern Iraq. In 1993, the ship made a historic visit to the Russian city of Vladivostok, and a year later, made a port visit to Qingdao in the People’s Republic of China. Two years later, Bunker Hill took up station south of Taiwan to monitor missile tests by China’s army.

In 1998, the ship switched homeports again from Japan back to San Diego. Following the shift, Bunker Hill deployed in late 2000 with the Abraham Lincoln Battle Group to again participate in Operation Southern Watch. It also conducted boarding and inspections on more than 40 vessels in support of UN sanctions against Iraq. In addition, Bunker Hill conducted humanitarian operations off East Timor and training exercises in Kuwait. Following the attack on USS Cole (DDG-67), the ship made way to Bahrain to provide support and protection for ships based there;- it remained at sea for 67 consecutive days. Bunker Hill finally returned to San Diego in February 2001.

In 2006, the ship was upgraded with the Aegis defense system, and later that year, deployed to the coast of Somalia to conduct antiterrorism operations as part of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Task Group. It returned to San Diego in March 2007 and was given the 2006 Battle “E” award. After modernization, Bunker Hill returned to sea in August 2009. During the deployment, it participated in Operation Unified Response, in which the crew provided critical care and aid to six Haitian villages. After returning from the deployment in the summer of 2010, Bunker Hill participated in multiple high-profile events to include the Portland Rose Festival and activities with Russian cruiser Varyag.

In November 2010, Bunker Hill was once again at sea. While operating in the Middle East, the ship provided support for Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. During the deployment, Bunker Hill, along with USS Momsen (DDG-92), averted a pirate attack on a tanker while patrolling in the Gulf of Oman by sinking two skiffs.

Although Bunker Hill is currently an active ship with its homeport still in San Diego, the Navy plans to take the ship out of commission in reserve next year.

Bonhomme Richard Captured Serapis

On Sept. 23, 1779, the frigate Bonhomme Richard, commanded by Capt. John Paul Jones, was in the North Sea off Flamborough Head, England, in company with Alliance and Pallas, when at about 3 p.m. a lookout shouted out that a large group of ships were approaching from the north. Guided by information he had received previously, Jones concluded that the vessels belonged to a 41-ship convoy coming from the Baltic Sea under the protection of British frigate Serapis and sloop-of-war Countess of Scarborough. Eager to confront them, Jones ordered maximum sail to close in on the enemy, but the wind was very light and some three and a half hours passed before they reached within striking distance. Meanwhile, British Capt. Richard Pearson, commanding the convoy from onboard Serapis, eyed the approaching ships suspiciously. Since they were still too far away, he could not tell what nationality they were, and Jones was flying British colors as a lure to get them into range of his cannons. Pearson, who was cautious, ordered the merchant ships to move toward the shoreline, where coastal defenses could defend them. With the valuable merchant ships protected under the guns of Countess of Scarborough, Pearson moved forward to determine the identity of the approaching squadron. As Jones closed in with his two escorts, he raised signal flags for the rest of the squadron to form a line of battle. They not only ignored the orders, but turned away entirely and left Bonhomme Richard alone as it closed with Serapis. Keeping his British colors aloft, Jones closed in on Pearson’s ship. The British captain called out to him, via speaking trumpet, “What ship is that?” Hoping to move in just a little closer, Jones responded that he was Princess Royal. Unconvinced, Pearson called out again “Where from?” and when he received no answer, he bellowed, “Answer directly or I’ll fire into you.” Jones gave his answer by hauling down the British colors and raising the American flag. Immediately, both ships unleashed full broadsides onto each other.

Pearson enjoyed a substantial firepower advantage, having 50 guns compared to Jones, who had 40. Jones’ disadvantage worsened dramatically when two of his 18-pounders exploded early in the battle. The twin blasts tore a hole in the ship and killed or horrifically injured their gun crews. The situation only got worse when Jones realized the remaining four 18-pounders were too old and defective to risk using. Knowing he had no chance in a gun duel with his now very inferior firepower, Jones tried to maneuver close enough to board Serapis. Bonhomme Richard came alongside Serapis at a poor angle. When Jones’ men tried to board, Pearson’s marines easily repelled them, and Jones pulled away. Pearson then made another attempt at firing a broadside, but Jones was careful to keep his ship from presenting itself at an advantageous angle for Pearson’s guns. While maneuvering, the two ships collided, with Bonhomme Richard’s bow striking Serapis’ stern. At this point, Jones realized his best chance was to get the two ships coupled together. He scrambled across the deck to grab the enemy’s forestay (rigging connected to the foremast) that had been cut and had fallen on the deck of Bonhomme Richard. Seizing it and tying it to his own ship, Jones managed to tie the two ships together in a deadly embrace. This took away Pearson’s advantage in firepower, because half of his guns were pointed away from Bonhomme Richard.

With the two vessels entangled, Jones’ crew went to work firing what guns they had left at Serapis’ rigging in hopes of disabling it, while simultaneously using small-arms fire and grenades on the enemy ship. Jones ordered his men to attempt a second boarding, but Pearson’s crew again was able to fight them off. However, these actions forced the British seamen on Serapis out onto the dock, creating easy targets for Bonhomme Richard’s sharpshooters. Jones suffered yet another setback when Alliance moved forward and unleashed the first of three broadsides not on Serapis, but on Bonhomme Richard. The commander of Alliance—former French naval officer Pierre Landais—and Jones had a longstanding feud that had come to a head when Bonhomme Richard and Alliance had collided months earlier. Later in his journals, Jones would claim Landais did it on purpose so he could sink Bonhomme Richard and take credit for sinking Serapis. Nevertheless, the ongoing feud would have to wait. His ship, as was Serapis, was in dire straits. Billowing smoke engulfed the decks as fires sprang up amid the debris of shattered timbers and shredded sails. As they scrambled to fight the battle, the crew of Bonhomme Richard also worked to make sure the flames did not reach the powder magazine.

While Bonhomme Richard’s small arms were having a devastating effect on Serapis and its crew, the British cannons were as equally successful. During the third hour of the battle, Jones found himself with only three small 9-pounders left on Bonhomme Richard’s quarterdeck. When one of the gunners suffered a severe head injury, Jones himself took over and began firing at the enemy mainmast. While he was hunched over the gun, one of the crew came up from below, and not knowing it was Jones firing the weapon, assumed his commander had either surrendered or was dead. Gunner’s Mate Henry Gardner grabbed two nearby crewmates and began to scream “Quarter! Quarter!” Jones, hearing their cries, became enraged. Turning on the men, he chased them down to the gun deck and finally hurled his pistol at Gardner, striking him in the head and rendering him unconscious. Pearson, meanwhile, heard the screams as well. “Have you struck? Do you ask for quarter,” he called out across the deck of Bonhomme Richard, not even bothering to use his speaking trumpet as the two ships still lay lashed together. At that moment, Jones famously replied, “I have not yet begun to fight!”

Pearson got the message and the fighting continued. At around 10:15 p.m., an enterprising seaman from Bonhomme Richard managed to get on one of the yards overhanging the British deck and dropped a grenade into an open hatch. The blast ignited powder cartridges that had been left scattered about the deck during the heat of battle, and triggered a series of explosions that blew guns off their carriages and blasted gaping holes in the side of the ship. Flames engulfed the gun deck, where many of the crew now confined themselves to avoid the constant sniper fire topside. At this point, both ships were in dire condition and it was just a matter of time before one of them would surrender. Reportedly, one of the seamen begged Jones to surrender, but he refused. “No! I will sink. I will never strike.” However, Pearson had had enough and at 10:30 p.m. struck.

Jones spent a day and a half trying to salvage Bonhomme Richard, but it was a hopeless effort. At about 11 a.m. on Sept. 25, Jones, watched “with inexpressible grief” from the deck of his new flagship as Bonhomme Richard disappeared beneath the waves. By all estimates, roughly half the crew of both ships were killed or seriously wounded in one of the longest and bloodiest naval battles of the American Revolution.

Kearsarge Provided Relief for Typhoon Vera Victims

On Sept. 29, 1959, aircraft carrier USS Kearsarge (CVS-33), with Helicopter Squadron 6 and other Seventh Fleet units, began six days of disaster relief for Nagoya, Japan, after Category 5 Typhoon Vera made landfall. Vera was the strongest and deadliest typhoon on record to make landfall reaching wind speeds of up to 160 miles per hour. Storm surges swamped vessels and overwhelmed seawalls and levees, landslides swept over communities, and multiple buildings collapsed, crushing or trapping people within. Vera killed and injured tens of thousands of people and rendered an estimated 1.5 million homeless.

After Kearsarge entered port, its aircraft landed parties of medical staff and supplies, while its crew and air group donated clothing and money to the distressed people. These endeavors included evacuating almost 6,000 persons, delivering 200,000 pounds of relief cargo, and administering more than 17,000 typhoid and antibiotic shots to prevent the spread of disease. In addition to Kearsarge’s support, all available servicemembers stationed in Japan were ordered to take part in typhoon relief efforts.

Economically, Typhoon Vera was a major setback for Japan, which was still recovering from World War II. As a result of the storm, the Japanese government created a disaster management council to ensure that national and regional governments would have measures in place to provide more effective emergency assistance in the aftermath of future storms. In addition to legislative reform, the breaching of flood defenses during Vera prompted a redesign of the mechanisms. In Nagoya, regulation was created for coastal construction and their heights. Development of flood defenses in Ise, Osaka, and Tokyo Bays were also set into motion. The heights of the defense systems were based on worst case scenarios and maximum storm surge heights caused by future typhoons. For more on the Navy’s humanitarian mission, visit NHHC’s website.

Washington Navy Yard Established

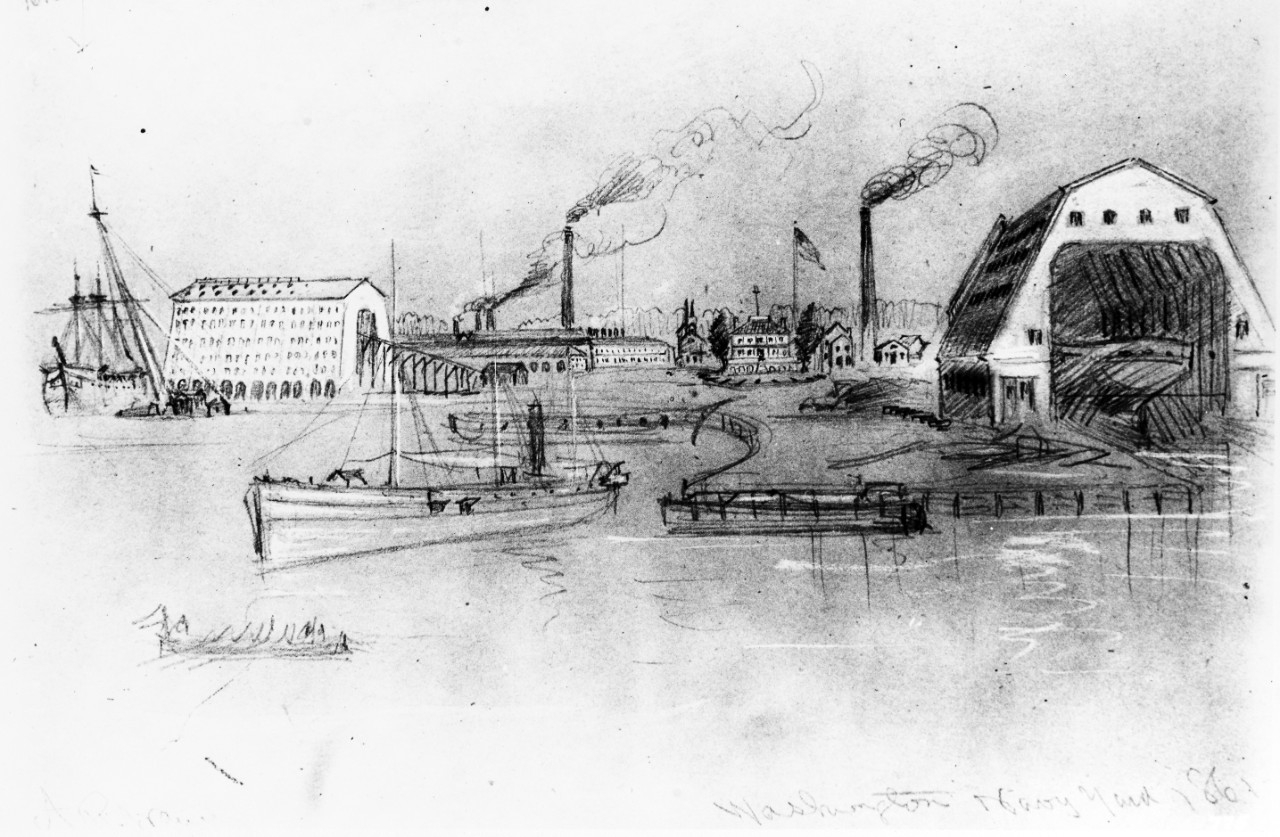

On Oct. 2, 1799, the Washington Navy Yard was established under the direction of Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert and the supervision of Commodore Thomas Tingey, who served as commandant of the District of Columbia navy yard for the next 29 years. As the nation’s first navy yard and homeport, shipbuilding and ship fitting were the dominant activities in the early years. Twenty-two vessels were constructed at the Washington Navy Yard that ranged from 70-foot gunboats to the 246-foot frigate Minnesota. In 1812, Constitution was moored at the yard for a refit in preparation for combat with Great Britain. During the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard remained an important support facility and a strategic location in the defense of the nation’s capital city. As the British stormed Washington in 1814, Tingey ordered the navy yard burned so that the enemy could not capture it. The only structures that were spared were the Latrobe Gate and the Tingey House (Quarters A), which are still standing today.

After the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard never regained its prominence as a shipbuilding facility. The waters of the Anacostia River, which border the south side of the yard, were deemed too shallow and mostly inaccessible for larger vessels. Therefore, a shift in the yard’s functions was undertaken and lasted more than a century—ordnance and technology. Early on, anchors, chains, and steam engines were manufactured at the Washington Navy Yard. After the Civil War, the yard was designated the manufacturing center for all ordnance in the Navy. The 14-inch naval railway guns used in France during World War I were manufactured at the Washington Navy Yard.

By World War II, the Washington Navy Yard was the largest naval ordnance manufacturer in the world. At its peak, the navy yard accommodated 188 buildings on 126 acres of land and employed nearly 25,000 people. Functions of the navy yard ranged from the construction of small components for optical systems to enormous 16-inch battleship guns. In December 1945, the Washington Navy Yard was renamed the U.S. Naval Gun Factory and ordnance work continued until it was phased out in 1961. Three years later, the facility was renamed the Washington Navy Yard and the factories used to make ordnance began to be converted to office space.

The Washington Navy Yard has also been the scene of multiple scientific developments. During the War of 1812, Robert Fulton conducted research and testing on his clockwork torpedo. Commodore John Rodgers built the nation’s first marine railway for the overhaul of large vessels, and John Dahlgren developed his distinctive bottle-shaped cannon that became the mainstay of naval ordnance. In 1898, David Taylor developed a ship-model testing basin that was used by the Navy and private shipbuilders to test the effects of the sea on new hull designs, and the first shipboard catapult for aircraft was tested on the Anacostia River in 1912. The gears for the Panama Canal locks were cast at the navy yard, and technicians applied their efforts to medical designs for prosthetic hands and molds for artificial eyes and teeth.

Due to its proximity in the nation’s capital, the Washington Navy Yard has also been a ceremonial gateway to dignitaries, diplomats, and political leaders. In 1860, the first Japanese diplomatic mission was welcomed at the navy yard. Abraham Lincoln was a frequent visitor during his presidency, and Great Britain’s King George VI visited the Washington Navy Yard during his stay. The navy yard also received the remains of World War I’s Unknown Soldier, and Charles Lindbergh returned to the Washington Navy Yard in 1927 after his world famous transatlantic flight.

Today, the facility supports a variety of activities, and serves as headquarters for the Naval District of Washington and numerous support activities. The National Museum of the U.S. Navy welcomes visitors daily to displays of art and artifacts that trace the Navy's history from the American Revolution to present day. Leutze Park is the scene of military ceremonies, and one of the anchors of USS Enterprise (CV-6)—the most decorated ship of World War II—is displayed there as well. In addition, the Naval History and Heritage Command calls the Washington Navy Yard home.