Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Lassen Commissioned—20 Years Ago

On April 21, 2001, USS Lassen was commissioned at Tampa, FL. The Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer is named after Lt. Clyde Everett Lassen, a Medal of Honor recipient, who rescued two downed aviators while he was commander of a search and rescue helicopter during the Vietnam War. On June 19, 1968, Lassen was under heavy enemy fire and initially landed in a clear area, but due to the dense undergrowth, the aviators could not reach the helicopter. With the aid of flare illumination, Lassen successfully accomplished a hover between two trees at the survivors’ position, but illumination was lost and the helicopter hit a tree. Lassen expertly maneuvered his helicopter in the clear and again attempted to land, but lack of light and being dangerously low on fuel nearly squashed the rescue. On the next attempt, fully aware he would come under enemy attack by exposing himself, Lassen turned on his landing lights, and the aviators were able to board the aircraft. Lassen made his way back to his ship with only minutes of fuel left.

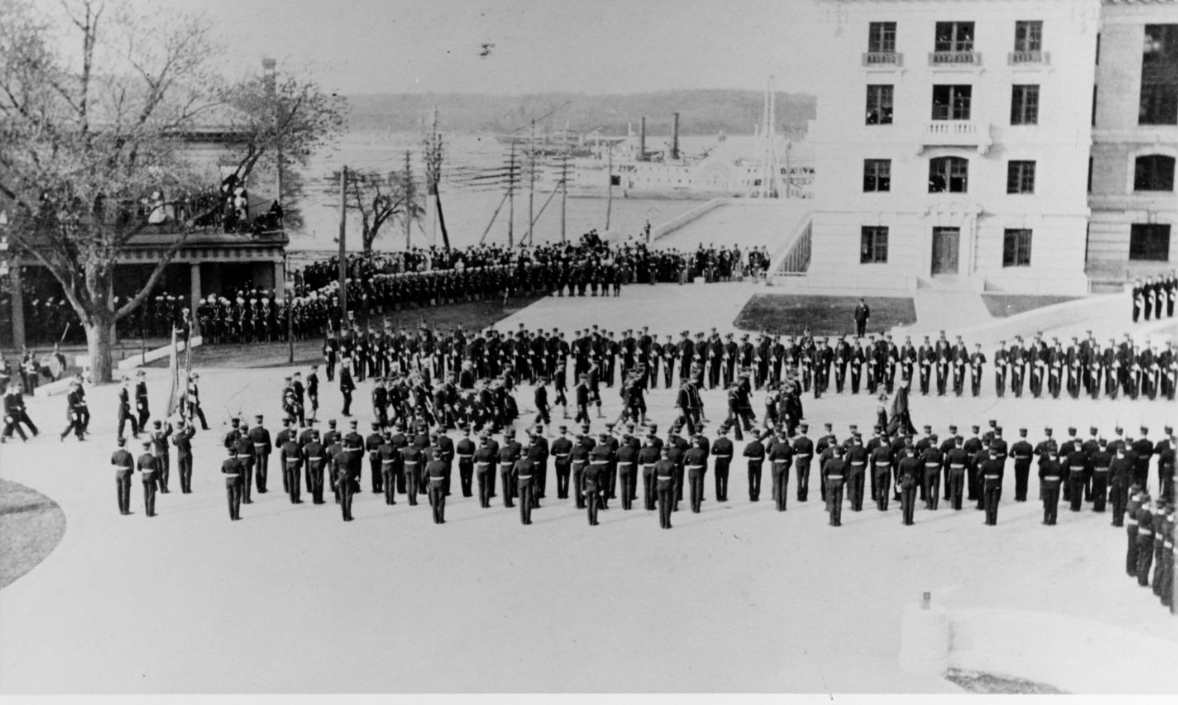

Jones Reburial Ceremony—115 Years Ago

On April 24, 1906, a reburial commemoration ceremony for Capt. John Paul Jones was held at the U.S. Naval Academy where President Theodore Roosevelt delivered a speech in honor of the legendary American Revolution naval captain. Jones helped establish the traditions of courage and professionalism that Sailors of the U.S. Navy today proudly maintain. He took the American Revolution to the enemy's homeland with daring raids along the British coast and the famous victory of Bonhomme Richard over HMS Serapis was legendary. During the engagement and after his ship began taking on water and fires broke out on board, the British commander asked Jones if he had struck his flag. Jones replied, “I have not yet begun to fight!” In the end, it was the British commander who surrendered. Jones is remembered for his indomitable will, and his unwillingness to consider surrender even when the slightest chance of victory existed. Throughout his naval career, Jones always promoted professional standards and training. Sailors of the United States Navy can do no better than to emulate the spirit behind Jones’s stirring declaration: “I wish to have no connection with any ship that does not sail fast for I intend to go in harm's way.” For more on Jones, check out his page in NHHC’s historical figures.

Preble Hall Podcast

In a recent naval history podcast from Preble Hall, the oldest extracurricular activity at the U.S. Naval Academy is now 176 years old. Joining Preble Hall to discuss their performance of “A Midsummer Night's Dream” are Professor Christy Stanlake and Midshipmen Tiara Sterling, Allen Sand, Rob Saunders, and Olivia Hunt. The Preble Hall podcast, conducted by personnel at the U.S. Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, MD, interviews historians, practitioners, military personnel, and other experts on a variety of naval history topics from ancient history to more current events.

Preservation Week

This year, April 25–May 1 is Preservation Week. Preservation Week is intended to promote the role of libraries and other institutions in preserving personal and public collections and treasures. Some 630 million items in collecting institutions require immediate attention and care. Eighty percent of these institutions have no paid staff assigned responsibility for collections care; 22 percent have no collections care personnel at all. As natural disasters of recent years have taught us, these resources are in jeopardy should disaster strike. The American Library Association encourages libraries and other institutions to use Preservation Week to connect our communities through activities and resources that highlight what we can do, individually and together, to preserve our shared collections. Learn about our collections at NHHC’s website.

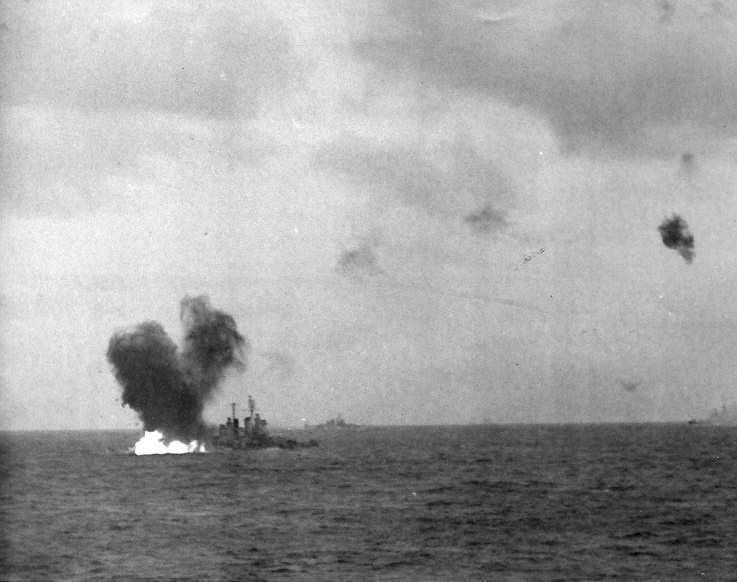

How Floating “Repair Yards” Helped the U.S. Navy Win in the Pacific

In a hard turn that left her underside exposed off Formosa in October 1944, personnel on the cruiser USS Houston felt the explosion of the torpedo strike across the ship. The commander of the ship, Capt. William Behrens, recalled “that all propulsive power and steering control was immediately lost. The ship took a list to starboard of 16 degrees. All main electrical power was immediately lost.” Subsequently, Behrens ordered that surplus hands evacuate to escorting ships, while damage control parties stayed onboard to keep the ship afloat. After nearly two weeks, Houston managed to limp more than 1,200 miles to Ulithi with the help of fleet tugs USS Pawnee, USS Zuni, and other ships. Houston, and many other ships during World War II, survived an attack due in part to the heroics of the crew, but equally to the unsung heroes of Service Squadron Ten. The forward deployed squadron allowed the Navy to conduct prompt and sustained combat operations close to the combat zone without returning to distant ports. They kept the fleet supplied, fed, fueled, repaired, and happy. The ability to regenerate combat power, close to combat operations due to service squadrons sustaining the fleet in forward areas of the theater, was a decisive advantage for the United States in the Pacific. For more, read the article.

Gemini VIII’s Near Disaster

On March 16, 1966, 55 years ago, Gemini VIII launched from Cape Canaveral, FL, with naval aviator Neil Armstrong at the helm. The astronauts, which included crewmate David Scott, completed seven orbits in 10 hours and 41 minutes at an altitude of 161.3 nautical miles. It was the first mission to link two spacecraft together in Earth’s orbit, but after 30 minutes, the crew was forced to undock with the Agena vehicle due to problems with Gemini’s control systems. When Gemini undocked from Agena, she began to spin and gyrate to the point where the astronauts could black out and die. Armstrong initially used the ship’s thrusters to stop the spin, but it immediately started again and began to get worse. Out of touch with Houston controllers and far from any tracking stations, Armstrong struggled to gain control, but to no avail. Armstrong, resourcefully, turned off the Orbital Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS) and activated the Reentry Control System (RCS), two rings of thruster rockets around the nose. After using three-quarters of their RCS propellants, he stopped the spin. Due to mission guidelines, Gemini had to immediately return to earth, but Armstrong’s decision saved their lives. For more, read the article. For more on the Navy’s role in space exploration, go to NHHC’s website.

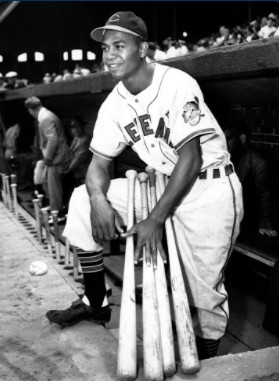

Baseball Legend Larry Doby Served in the Navy During World War II

Lawrence “Larry” Eugene Doby was the second African American baseball player to break Major League Baseball’s color barrier signing with Cleveland in July 1947, just three months after Jackie Robinson made history when he signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was the first to go directly from the Negro Leagues into MLB. Prior to his historic debut in baseball, he served from 1943–1946 in the U.S. Navy. He was stationed stateside at several locations and in 1945, he served on Ulithi—a volcanic atoll between Guam and the Philippines. The island was a major staging area for the Navy’s campaign across the Pacific during its final push to secure the Philippines and begin the invasion of Japan during World War II. After the war, Doby briefly played for the San Juan Senators in Puerto Rico before joining the Negro League. After he was signed in the big leagues, he played for the Indians until 1955 and then he bounced around with several other teams. Over the course of his career, he was a seven-time all-star, World Series champion, and two-time American League homerun champion. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998. For more, read the article. For more on Navy athletics, go to NHHC’s website.

Webpage of the Week

This week’s Webpage of the Week is new to NHHC’s notable ships. Frigate Chesapeake was launched on Dec. 2, 1799, at the Gosport Navy Yard, VA, and commissioned on May 22, 1800. The ship was one of six frigates authorized by Congress with passage of the Naval Act of 1794. On April 1, 1813, Capt. James Lawrence, commander of Chesapeake, set sail from Boston Harbor with half of his officers and around one quarter of the crew new to the ship. He ordered his ship to sail in HMS Shannon’s wake hoisting a banner with the motto, “Free Trade and Sailors Rights.” Shannon was attempting to blockade Boston Harbor. At around 4:30 p.m., Shannon pointed her bow southeast as Chesapeake followed at about 6–7 knots. Lawrence intended to bring the ships yard arm to yard arm, but the British commander anticipated the move and prepared his starboard battery. At 5:45 p.m., Chesapeake approached Shannon’s starboard. As the ships neared pistol range, both exchanged broadsides. Shannon’s broadsides and small arms fire decimated Chesapeake’s rigging, killing three men at the wheel including the sailing master. Within the next few minutes, almost 100 were killed or wounded on Chesapeake’s spar deck including nearly all the officers. Lawrence, who had been mortally wounded and below decks when the ship was boarded, uttered the famous words “Don't give up the ship,” although at that point it was too late. Within minutes after Shannon’s crew boarded Chesapeake, the fighting was over and the white ensign of St. George flew over Chesapeake. For more on the story of Chesapeake, check out the page today. It contains a short history, suggested reading, and selected imagery.

Today in Naval History

On April 20, 1964, Lafayette-class submarine USS Henry Clay launched a Polaris A-2 missile in the first demonstration to show that Polaris submarines could launch missiles from the surface as well as from beneath the ocean. Between 1963 and 1967, the Navy built 19 Lafayette and James Madison-class and 12 Benjamin Franklin-class fleet ballistic missile submarines. The first eight of these vessels built were armed with the A-2 missile and the rest with A-3 missiles equipped with multiple reentry vehicles. The U.S. Navy built 41 fleet ballistic missile submarines during the '50s and '60s to include the George Washington and Ethan Allen-class submarines, dubbed “41 for Freedom,” loaded with a combined total of 656 missiles. For a brief history of U.S. Navy fleet ballistic missiles and submarines, go to NHHC’s website.

For more dates in naval history, including your selected span of dates, see Year at a Glance at NHHC’s website. Be sure to check this page regularly, as content is updated frequently.