Operation Homecoming

28 January 1973 – 4 April 1973

Twenty telephones sat silent and sentinel along an L-shaped desk at the Joint Command Processing Center (JCPC) at Clark Air Force Base (AFB) on Luzon. Although it was the end of January 1973, the skies were overcast but the temperature was pleasant. A line of wall-mounted clocks displayed times in Hanoi, Hawaii, Washington, D.C., and Zulu local time—ticking away the seconds, minutes, and hours until the JCPC would become a flurry of voices and commands, directing hospital planes to various locales.[1]

Operation Homecoming—formerly Operation Egress Recap—had been in the works for nearly five years, with the joint operation ready to deploy at a moment’s notice by 1973.[2] At its core, Homecoming intended to reduce the amount of time between the liberation of a prisoner of war (POW) from compounds across Southeast Asia, and their return to the mainland United States. Americans were optimistic of a peace accord in late 1972.[3]

American newspapers reported over 1,200 military personnel, mostly airmen, listed as missing in action (MIA). Dr. Roger E. Shields, Chairman of the Prisoner of War and Missing in Action task force under Assistant Secretary of Defense G. Warren Nutter, told reporters in late-January 1973, “all our plans are in a high state of readiness, just as they were in October, awaiting word that the prisoners have been released—and where.”[4]

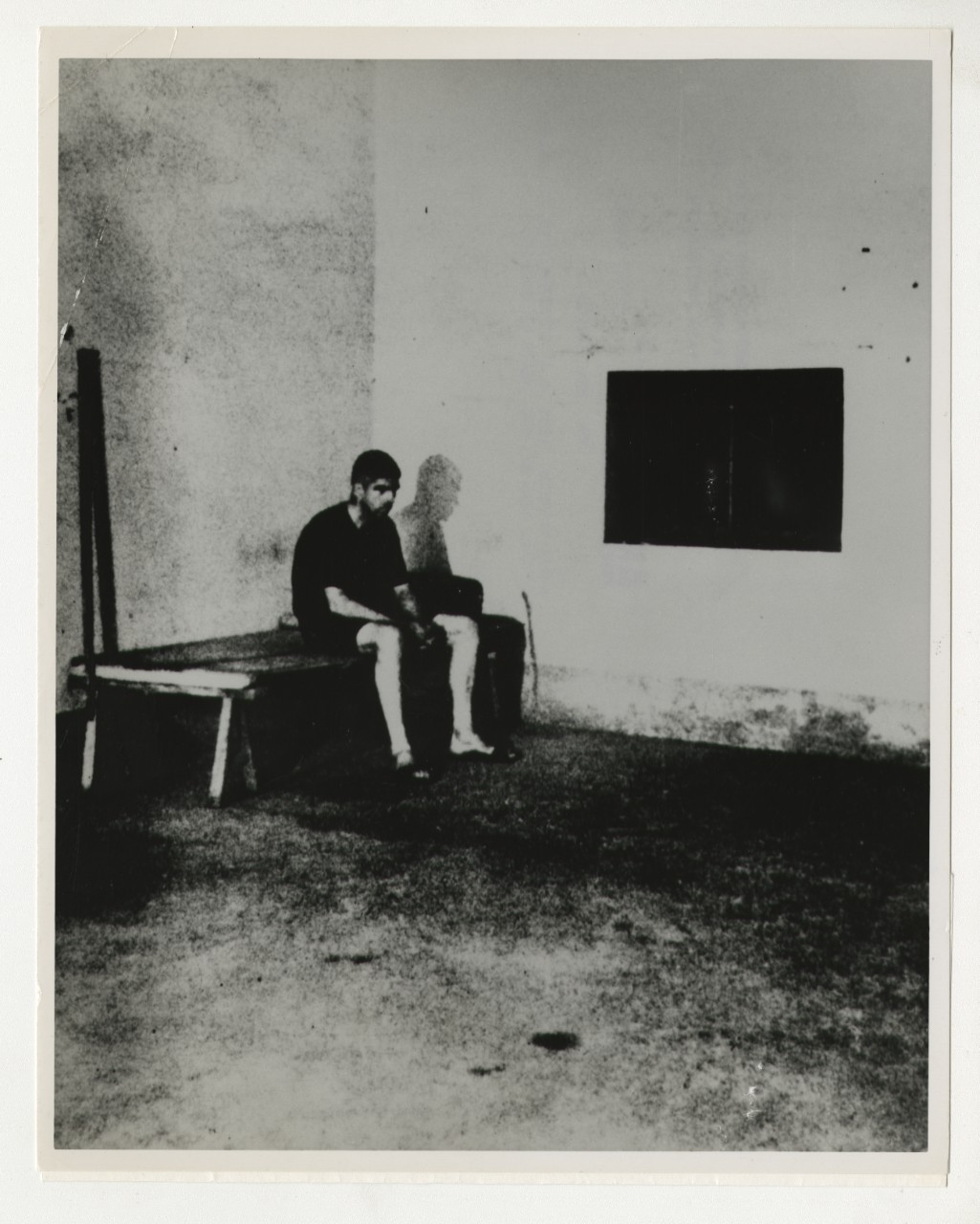

Then-Lieutenant Commander Richard A. Stratton, USN, Prisoner of War, held by North Vietnamese communists in late 1969. (L-53-36-002-F)

In advance of the rehabilitation and repatriation of the 591 American POWs from Vietnam—325 Air Force, 138 Navy, 77 Army, 26 Marines, and 25 civilians—COMNAVMARIANAS delivered all necessary processing gear, which included personnel, intelligence, and medical records; medical and dental evaluation forms, and uniforms to COMNAVPHIL. The 13th Air Force at Clark AFB provided the working and ready storage spaces on station for the operation.[5] Operation Homecoming was a three-phase operation that involved the initial reception (Phase I), initial processing (Phase II), and detailed processing (Phase III) of all returnees.

Civilians Douglas Ramsey (center) and James U. Rollins (left) await release by the Viet Cong to American authorities on 12 February 1973. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration (DD-ST-99-04408).

Phase I involved the transfer of the returnee into U.S. control. For the returnees, this phase was simply transit, as they awaited aeromedical evacuation to one of the three JCPCs at Camp Kue, Okinawa; Naval Hospital, Guam; or Clark Air Force Base (AFB), Philippines. All Navy returnees processed through Clark AFB (see Table 1). Twenty Military Airlift Command (MAC) C-141 and PACAF C-9A medevac flights brought returnees to the Joint Homecoming Reception Center (JHRC) at Clark AFB from Hanoi, Saigon, and Hong Kong.[6] The arrival of Navy returnees at the JHRC initiated Phase II in which their administrative and medical processing began in earnest. Processing teams provided legal aid, spiritual support, and public affairs guidance. Phase III began when the Navy returnee touched down in the United States following aeromedical evacuation from Clark AFB.[7]

Table 1. NAVY RETURNEE CHRONOLOGY

28 JANUARY |

Operation Homecoming begins |

12 FEBRUARY |

43 Navy returnees arrived |

18 FEBRUARY |

4 Navy returnees arrived |

4 MARCH |

36 Navy returnees arrived |

14 MARCH |

31 Navy returnees arrived |

27 MARCH |

2 Navy returnees arrived |

28 MARCH |

9 Navy returnees arrives |

29 MARCH |

13 Navy returnees arrived |

4 APRIL |

Operation Homecoming formally disestablished. |

Adapted from H. F. Griffith, “Chronology of Events,” Part II, Attachment B in “Operation Homecoming, Navy After Action Report,” April 8, 1973, Folder 2, Box 92, CNO and BuPers: POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington D.C.

An unidentified returnee deplanes at Clark AFB in Luzon and greeted by LGEN William G. Moore Jr. (left), Commander 13th Air Force, as Admiral Noel Gaylor (right), Commander Pacific Command greets another returnee. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration (6504305).

The Navy deployed a “Homecoming Processing Team,” consisting of ninety-three personnel that included a contingent of forty-seven debriefer-escorts. This team converged at the JCPC at Clark Air Base on 28 January 1973. An additional twenty debriefer-escorts arrived on 8 February, bringing their team to 113 personnel.[8] In a memorandum from Captain H. F. Griffith, PACOM JCPC Deputy Commander, Griffith identified the primary responsibility of debriefer-escorts as establishing a “close rapport” with their returnee and assisting “in every way possible to make his transition from captivity to freedom as stress-free as possible.”[9] One of the many duties of each debriefer-escort was to maintain custody of the returnee’s personnel processing file, ensure the accuracy of all data included in the file, and to be familiar with its contents. Debriefer-escorts were on call 24 hours each day “to assist or talk to the returnee,” and were to seek out medical assistance and, sometimes, spiritual counseling from the attending physician or chaplain, as necessary. In this sense, debriefer-escorts took on the unofficial role of confidant and friend, even assisting their returnee in placing phone calls to family members and with letter-writing. The debriefer-escorts were also responsible for scheduling and monitoring the processing progress of their individual returnees.[10] On average, debriefer-escorts and medical personnel completed a returnee’s initial processing in 68 hours.[11]

LCMDR Everett Alvarez looks at a letter in his room at Clark AFB in Luzon on 1 February 1973. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration (DD-ST-99-04308).

Navy CPT Jeremiah Denton Jr. of Virginia Beach, Virginia, was the first of the initial forty-three released POWs to step off the first plane from Hanoi to Luzon on 12 February 1973.[12] In a short statement before departing to the United States three days later, Denton voiced his gratitude, and that of his cohort of returnees, before a crowd of news media: “I would like to express our thanks to you people here at Clark. You have shown us that your feeling is as deep as ours, and that is the highest compliment I can pay for the wonderful welcome we received here.” He went on to thank President Richard Nixon and all persons, military and civilian, associated with Operation Homecoming, “for an experience we will never forget.”[13] Greeted by an adoring crowd at Travis Air Force Base outside Sacramento, California, Denton touched down in the United States on 18 February 1973.

CPT Jeremiah Andrew Denton stands at the microphones and talks to the crowd of well-wishers and press upon his arrival on the C-141 Starlifter from Clark AFB on 18 February 1973. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration (DD-ST-99-04274).

Thirty-six MAC C-141 medevac flights transported Navy returnees from the JHRC to the United States, initiating Phase III of Operation Homecoming.[14] This phase included, even centered, Navy spouses and the children of returnees. Commander G. E. Hill, Public Information Officer for COMNAVAIRPAC, led a briefing for the wives of NAVAIRPAC naval aviators deployed in Southeast Asia, “should misfortune befall their husbands during their tour.” CDR Hill explained in thorough detail the process the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) initiated upon its receipt of a casualty message. A staff officer and chaplain made the much-dreaded phone call to the next-of-kin. With the news media alerted to casualty messages, BUPERS engaged in “a game” CDR Hill called “Beat the Press,” in which Navy officials strove to “beat the first call from the reporters.” Generally, they were able to do so. Hill cited one instance in which a family was notified “approximately seven minutes” before receiving calls from the press for comment. Once the casualty section in Washington, D.C. received notification, a standard telegram would be sent out to the primary and secondary next-of-kin, spouse, and parents or guardians, respectfully. Hill reminded the spouses that, should this circumstance come to pass, they would “be besieged with telephone calls and press queries,” and recommended they simply not talk to the press.[15]

Most Navy returnees landed at Travis Air Force Base before continuing on to naval hospitals in California, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington.[16] These former POWs were welcomed to a cacophony of cheers, jubilation, and fanfare. The Command Information Bureau at Balboa Naval Hospital prepared a commemorative "photofeature" (17.9 MB PDF download) of photographs that center the return experience of several Navy and civilian returnees. Some of these photographs depict candid and intimate moments of anticipation, elation, and, in some instances, sorrow as wives, children, and extended family embrace returnees for the first time in many years.[17]

In this photo from the FAPL scrapbook, Commander Richard Mullen is greeted by his wife, Jean, and daughters, Sandra and Karen. The Viet Cong captured Commander Mullen after he was shot down during a combat mission on 6 January 1967. (Box 10, Folder 2, Brent Baker Papers, Archives Branch, NHHC)

On Wednesday, April 11, 1973, President Nixon took a meeting with Dr. Roger Shields in the presence of Brent Scowcroft, Nixon’s Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs. While a brief fifteen minutes—most of which involved pleasantries—the conversation transcript not only shows Nixon’s pride in the work done by the POW/MIA task force, but his desire to maintain, if not increase, the positive publicity. Nixon told Shields, “These men can inspire and we shouldn’t lose this opportunity.” After Shields agreed, Nixon continued, belying “the pitiful attempt of the left to say their statements were brainwashed,” alluding to the statement given by Captain Denton prior to his departure for the United States.[18] Shields described the first group from Hanoi as “great,” recalling the bus turning a corner with the men smiling at him with “their thumbs up.” A sailor was the first off the bus and, on crutches, “He said, ‘Form up.’ They [sic] men stood tall and proud. They marched through the gate and the Commander [Captain] threw his crutches down and hugged me and said ‘I am home.’ On the plane, Denton said, ‘We wanted to return with honor. Did we?’” Shields assured the President, “They sure did.”[19]

Between 12 February and 4 April 1973, 566 U.S. military personnel, 23 American civilians, and 5 country nationals passed through the JHRC at Clark AFB. On 2 October, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs determined that no evidence existed indicating that “any U.S. Serviceman unaccounted for in Southeast Asia remained alive and in captivity by hostile forces.” As a result, PACOM phased out the receiving center on Guam, but maintained a contingency plan to reestablish it with 30 days’ notice if necessary. The facility at Clark AFB phased down, maintaining minimum provisions as of 1 December 1973.[20]

—Heather M. Haley, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, February 2024

----

[1] “Staff Poised for Return of POWs,” Daily Times-Advocate (Escondido, CA), February 1, 1973, 1; James P. Sterba, “U.S. Units in Philippines Poised for P.O.W. Airlift,” New York Times, February 11, 1973, 1; H. F. Griffith, “Chronology of Events,” Part II, Attachment B in “Operation Homecoming, Navy After Action Report” [hereafter “Operation Homecoming, Navy AAR”], April 8, 1973, Folder 2, Box 92, CNO and BuPers: POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington D.C. [hereafter POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC].

[2] Carl O. Clever, CINCPAC Command History 1973 (Oahu: Camp H. M. Smith, 1974), II: 599.

[3] Frank Macomber, “Nixon Began as War Protests Grew,” Daily News-Post (Monrovia, CA), January 27, 1973, A-2.

[4] Roger E. Shields quoted in Macomber, “Nixon Began as War Protests Grew,” A-2.

[5] H. F. Griffith, “Operation Homecoming, Navy AAR,” April 8, 1973, 4, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[6] Clever, CINCPAC Command History 1973, II, 600.

[7] B. A. Clarey, “CINCPACFLT CONPLAN 5111 Plan Summary,” undated, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[8] H. F. Griffith, “Operation Homecoming, Navy AAR,” April 8, 1973, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[9] H. F. Griffith to Egress Recap (Navy) Debriefers/Escorts, memorandum, “Egress Recap Debriefing and Escorting Duties,” January 8, 1973, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[10] H. F. Griffith to Egress Recap (Navy) Debriefers/Escorts, memorandum, “Egress Recap Debriefing and Escorting Duties,” January 8, 1973, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[11] Clever, CINCPAC Command History 1973, II, 600.

[12] “Sees Spouse, Shrieks,” Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa), February 12, 1973, 1.

[13] Jeremiah Denton quoted in James P. Sterba, “Clark Base Gets Thanks of P.O.W.’s: Men Boarding Plane to U.S. Express Gratitude for ‘Wonderful Welcome,’” New York Times, February 15, 1973, 16.

[14] Clever, CINCPAC Command History 1973, II, 600.

[15] G. E. Hill, “Briefing presented to the wives of NAVAIRPAC naval aviators deployed to the Western Pacific,” undated, Folder 2, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[16] J. M. Zacharias, “List of Navy Returnees in Operation Homecoming,“ April 12, 1973, Folder 1, Box 92, POW and MIA Records, 1964-1981, NHHC.

[17] Command Information Bureau Operation Homecoming Photofeature (San Diego: Fleet Air Photo Lab, 1973), Folders 1 and 2, Box 10, Brent Baker Papers, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C.

[18] Richard Nixon, “Memorandum of Conversation,” April 11, 1973, GRF-0314, Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[19] Roger Shields, “Memorandum of Conversation,” April 11, 1973, GRF-0314, Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor, MI.

[20] Clever, CINCPAC Command History 1973, II, 603.