William Maxwell Wood, the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron, and the Conquest of California

British Library digitized image from page 8 of "Reise um die Welt und drei Fahrten der Königlich Britischen Fregatte Herald nach dem nördlichen Polarmeer zur Aufsuchung Sir J. Franklin's in den Jahren 1845-1851. ... Zweite Auflage"

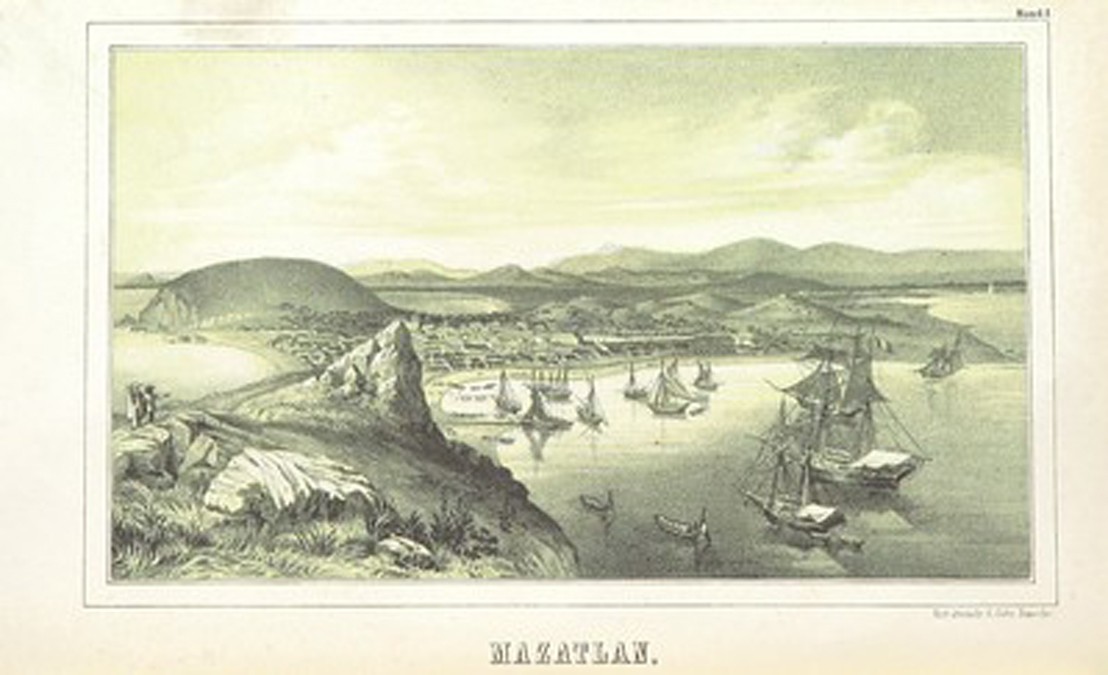

In early January 1846, William Maxwell Wood walked the streets of Mazatlán—a port city on Mexico’s Pacific coast. Wood was the fleet surgeon of the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron, which was anchored in the harbor. Though the town itself, with its “light and cheerful appearance,” was physically unchanged from Wood’s last visit exactly a year before, the mood among its residents had shifted. Things felt tense, he recalled, even “feverish.” On New Year’s Eve, General Mariano Paredes had assumed the Mexican presidency in a coup d’état. Just two days before that, at the behest of expansionist President James K. Polk, the United States had annexed the Republic of Texas, making the former Mexican territory its twenty-eighth state. There were similar rumblings of unrest in the Mexican possession of California, encouraged by the swell of American settlers. As Wood surveyed an uneasy Mazatlán, the United States and Mexico sat on the brink of war, mired in a dispute over the Texas border.

News traveled slowly in the 1840s, and neither Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the Pacific Squadron, nor the local authorities in Mazatlán could be certain if the two nations remained at peace or war. “The slightest event, the galloping of a horse through the street, or an unusual noise during the night,” Wood later wrote, “was attributed to deep motives, or regarded as connected with important events.” Though he did not know it yet, Wood himself would play the consequential role in supplying the first report of war directly to Sloat—a development that would have massive strategic implications.

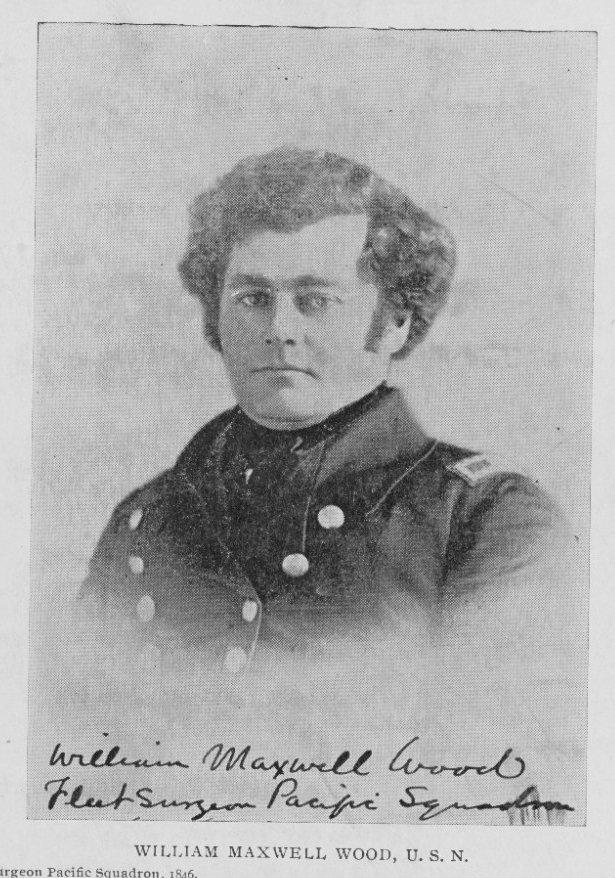

Born in Baltimore in 1809, William Maxwell Wood joined the Navy as an assistant surgeon in 1829. In the 1830s, he saw action in the Second Seminole War and in antipiracy and slave trade patrols in the West Indies. In 1843, Wood became the Pacific Squadron’s fleet surgeon. In his three-year tour, he traveled the length and breadth of the Americas and Polynesia. With a travel writer’s eye for detail and taste for adventure, Wood went ashore wherever the fleet anchored, often roaming deep into the countryside. At the summit of Mauna Loa in Hawaii, for example, he trekked into the smoldering volcanic crater, feeling the heat of the magma under his feet. Among Peruvians in colorful ponchos and hats, he took in a bullfight outside Lima, watching the ostensible matador—a convicted criminal—get pummeled by the beast. And from a Catholic mission in the central valley of California, he observed a local rebellion against Mexican authorities as it unfolded around him. Along the way, he learned Spanish.

By May 1846, Wood and the Pacific Squadron remained in Mazatlán. While war rumors persisted, there was no longer any guarantee that trusted communications could cross Mexico without first being intercepted by the authorities. At the same time, Wood was nearing the end of his tour of duty. Together with the American consul at Mazatlán, John Parrott, he agreed to return to the United States overland, traversing through the heart of Mexico. The route would take Wood and Parrott from San Blas on the Pacific coast through Guadalajara and Mexico City to Vera Cruz on the Gulf. Sloat ordered Wood to gather intelligence and send it back to the Pacific Squadron. The commodore’s concern in receiving the earliest possible notice of a declaration of war had less to do with Mexico and more to do with the machinations of another geopolitical rival—Britain. “Whether correctly or not,” Wood later wrote, “it was believed, that in case of war [with Mexico], the British squadron would attempt to take California under its protection.” Wood counted a dozen British vessels active in the Pacific and poised to occupy California, including the 80-gun ship of the line Collingwood. By providing Sloat with the most up-to-date intelligence, he could give the U.S. Navy a significant head start over the British.

On 4 May, Wood and Parrott set off on horseback, trailed by several pack mules. They were confronted with the usual hazards of travel across Mexico. Bandits often harassed the roads, robbing travelers of their possessions. But the political and military context made their journey even more dangerous. If Wood and Parrott’s identities were betrayed, they might be arrested as spies, and the contents of Wood’s luggage—his U.S. Navy uniform and a sheaf of dispatches addressed to the Secretary of the Navy—left them especially vulnerable to charges of espionage.

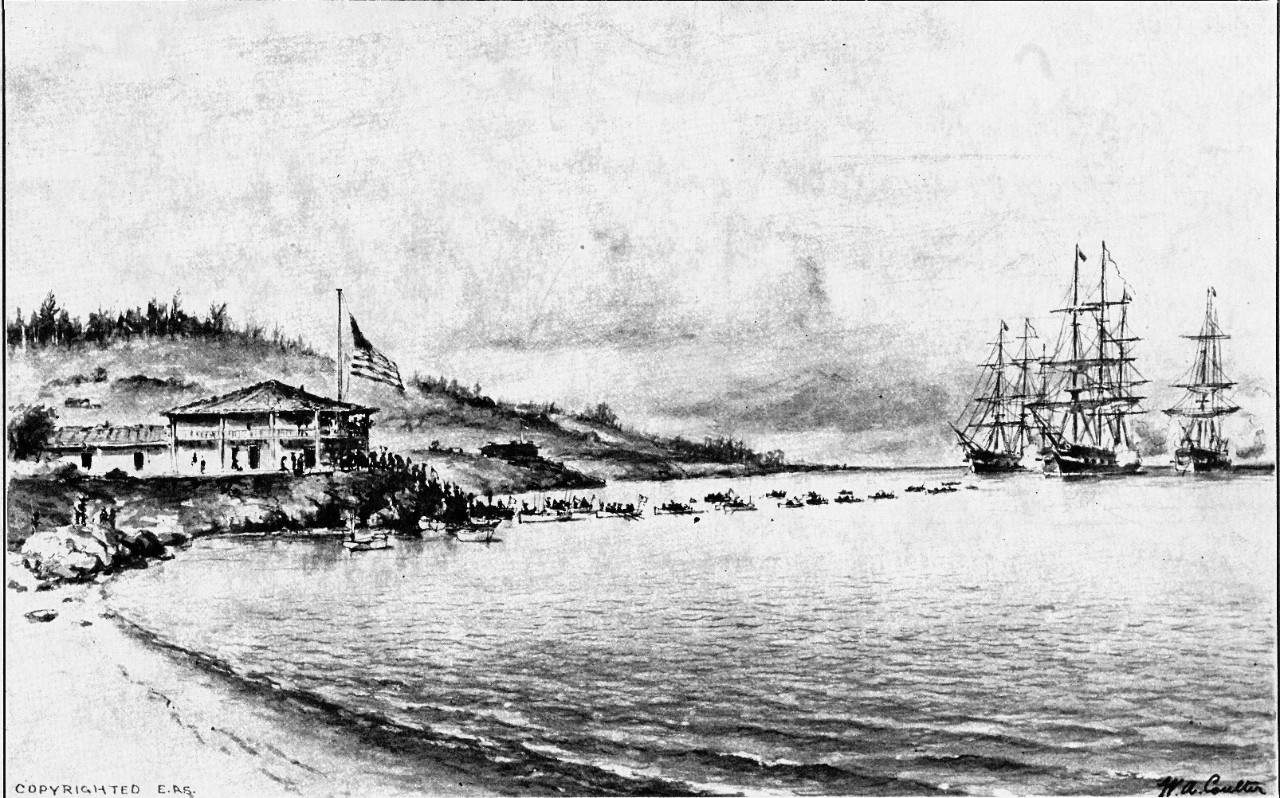

After a close call with an especially attentive customs agent outside Guadalajara, the two men entered the city, only to hear newspaper boys announcing that fighting had broken out in Texas. The war had begun. Wood acted swiftly, dispatching to Sloat details of the Battle of Palo Alto at small outpost in the Rio Grande valley called Fort Texas. As the commodore later told Wood, “The information you furnished me at Mazatlán… was the only reliable information I received of that event, and which induced me to proceed immediately to California.” The Pacific Squadron reached Monterey on July 7 and seized the town without firing a shot. They later took Yerba Buena—today, the site of San Francisco—as well as San Diego and Los Angeles. Ten days later, the British ship Collingwood sailed into Monterey Bay only to see the American flag flying over the town; it left the area immediately. The United States never relinquished its control over the territory, and four years later, after the Compromise of 1850, California entered the union as the thirty-first state.

With war officially declared, Wood and Parrott now found themselves in even greater danger. They continued on their journey to the Gulf coast, transiting first through Mexico City, where a discrete Irish tailor removed the epaulets from Wood’s concealed Navy uniform. Posing as an Englishman, Wood inspected the defenses of Chapultepec Castle before the two men departed in haste, eager to make contact with the U.S. blockading squadron at Vera Cruz. On 30 May, nearly a month after they had set out, Wood and Parrott reached the eastern port, where Wood enlisted the help of a small German vessel to take them to the U.S. flagship. Once on board, the commander immediately dispatched Wood to Pensacola on the steamer Mississippi, where he made his way to Washington, D.C.

Wood’s supporting role in the jockeying of great powers was a footnote in his long and illustrious career in Navy medicine. But he would continue to have a knack for being in the right place at the right time to witness important historical events. In the 1850s, he served as fleet surgeon of the Navy’s East India Squadron, observing engagements in the Second Opium War in China. During the Civil War, he found himself a spectator to the famed battle of the ironclads—USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (later renamed Merrimack). In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Wood to serve as Chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, and in March 1871, under the terms of the Naval Appropriation Act, he became the first Navy Surgeon General, with the rank of commodore.

William Maxwell Wood was retired for age in October 1871, but he continued to serve the Navy in a civilian capacity for another two years. He died outside his native Baltimore on 1 March 1880.

—Joel Hebert, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, February 2021

****

Sources:

Francis A. Knapp, Jr., “Biographical Traces of Consul John Parrott,” California Historical Society Quarterly 34, 2 (June 1955): 111-124.

George Cumming McWhorter, Incident in the War of the United States with Mexico, Illustrating the Services of Wm. Maxwell Wood, Surgeon, U.S.N. in Effecting the Acquisition of California

William Maxwell Wood, Wandering Sketches of People and Things in South America, Polynesia, California, And Other Places Visited, During a Cruise on Board of the U. S. Ships Levant, Portsmouth, and Savannah (1849)

William Maxwell Wood, Fankwei, Or, the San Jacinto in the Seas of India, China, and Japan (1859)