Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Fort Fisher

North Carolina

December 1864–January 1865

Background

In January 1861, the state of North Carolina remained divided on the subject of secession. On 9 January, local militia prematurely seized Forts Johnston and Caswell on the Cape Fear River near Wilmington. However, Governor John W. Ellis was not prepared to commit to secession formally. He orchestrated the return of the forts to the federal government. This act was a short-term concession in the wake of an act of rebellion.

Three days after the fall of Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers from the militia of the loyal states for three months of service. Governor Ellis had to make a choice. He refused to send any militia from North Carolina. This decision initiated the state’s first acts of war. On 16 April, North Carolina state militia seized Forts Caswell and Johnson for the second time.1

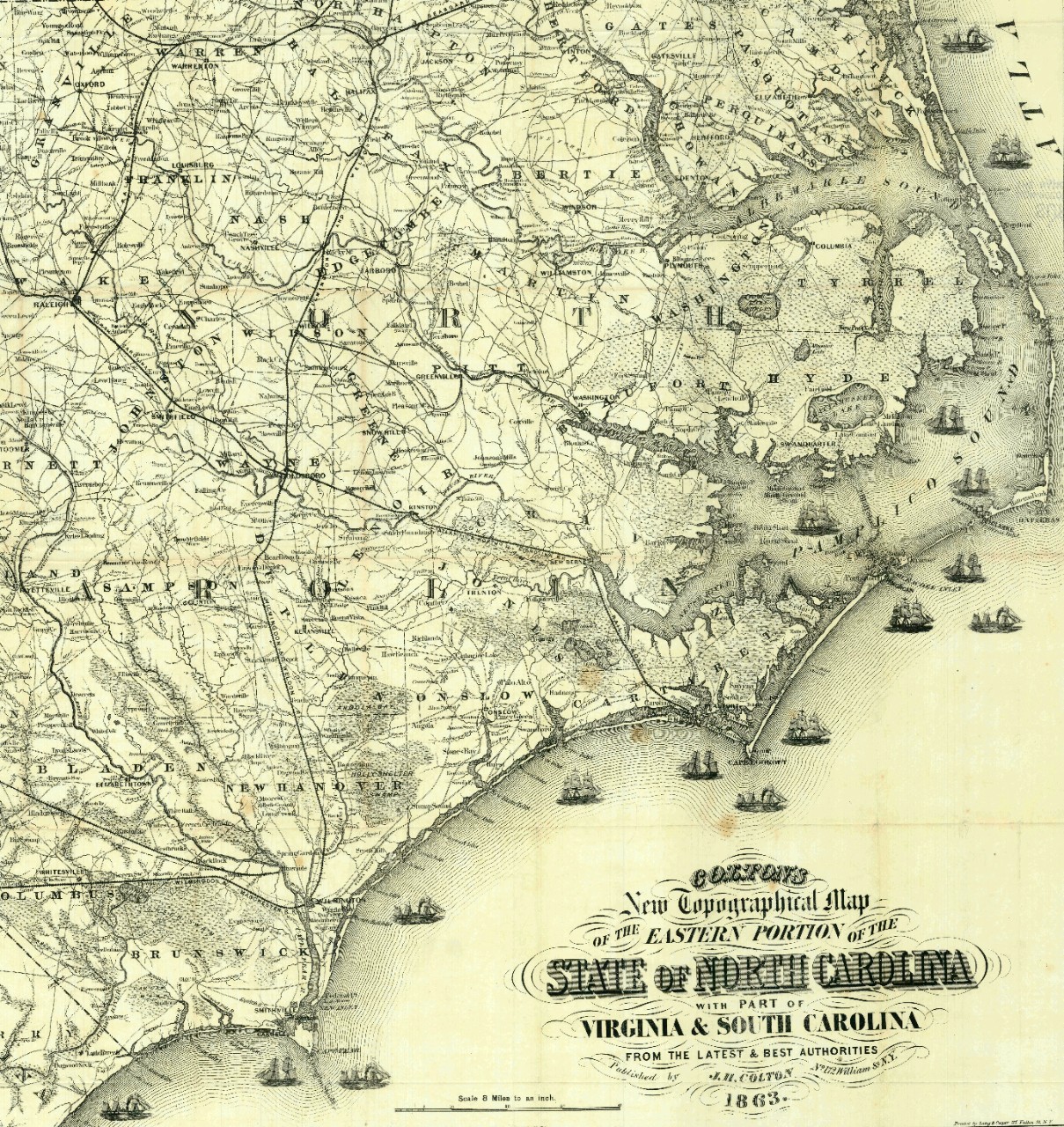

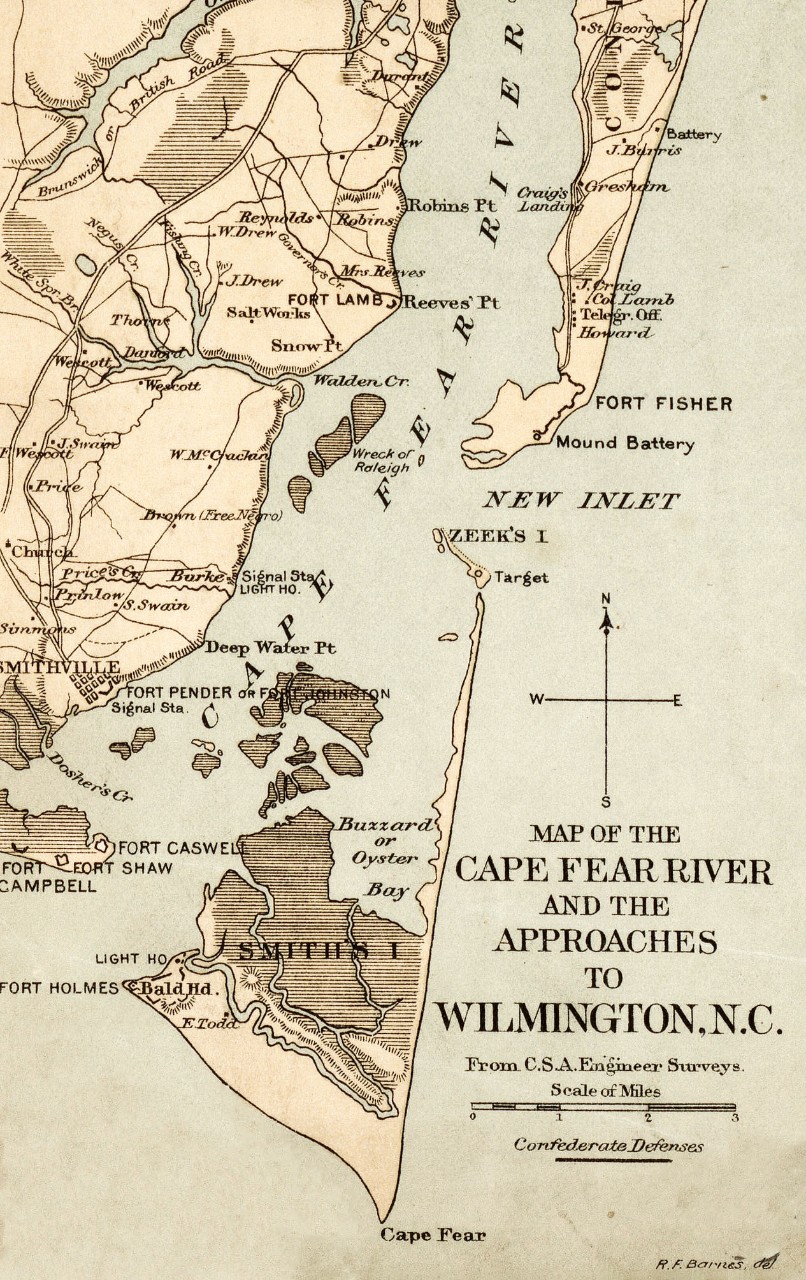

Map of the Cape Fear River and the approaches to Wilmington, North Carolina, 1862, drafted by Confederate army engineers. It was first published by the Norris Peters Co., Washington, DC. (Library of Congress [LC], 2014588297)

As soon as Ellis made the decision to ally his state with the Confederate cause, he began receiving aid from the provisional Confederate army. Major William H. C. Whiting, formerly of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was assigned to the coastal defenses at Cape Fear.2 Having already served in Charleston during the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Whiting quickly began writing requests for more ordnance while making plans to build a new defensive position six miles north of Fort Caswell.

On 19 April, Lincoln proclaimed a blockade of all southern ports. On the same day, Ellis ordered all of the state’s lighthouses to extinguish their beacons. On 27 April, Lincoln decided to extend the blockade to include Virginia and North Carolina. The state legislature of North Carolina officially voted for secession on 20 May 1861.

During this period, Wilmington was a prosperous transportation hub with two shipyards and three railroads, including the Wilmington and Weldon (W&W), which connected with lines running into Virginia. In June 1861, British vessels sailing into Wilmington continued to elude the federal government’s “paper blockade.”3 As long as Wilmington remained open, blockade runners could continue to supply the Confederate forces in the eastern theater. The W&W soon became known as the “lifeline of the Confederacy,” and Wilmington was its anchor.

The geographically protected port of Wilmington is located 20 miles up the Cape Fear River from the Atlantic coastline. Two inlets provided access to the river, separated by the 11-mile-long Smith’s Island. The Frying Pan Shoals extending from the tip of Cape Fear increased the distance between the two inlets to approximately 40 miles. This distance made it difficult for a small blockading fleet to be effective against blockade runners. In addition to its natural defenses, Wilmington was protected by a system of fortifications guarding each entrance to the river.

A series of earthen forts protected the Western Bar (Old) Inlet to the Cape Fear River, but a new fort was necessary to defend the river’s second entrance at the New Inlet. Major Charles P. Bolles was the civil engineer responsible for erecting the first battery on Federal (renamed Confederate) Point. This battery was the first redoubt of what became Fort Fisher, named after Colonel Charles F. Fisher.

Colonel Fisher, of the 6th North Carolina regiment, was among the first North Carolinians sent north to Virginia to fight with the Confederate forces in 1861. He died on 21 July 1861 during the first battle of Manassas.

In July 1862, Colonel William Lamb arrived to take command of Fort Fisher. Lamb spent the next two years transforming the disconnected series of earthworks into a continuous earthen fortification stretching across the peninsula and for a mile down the water’s edge. Its two faces, one facing the land and the other facing the sea, created the shape of upside-down L. The seaward face terminated at the point in a 60-foot high earthwork called Mound Battery. This conically shaped battery housed two heavy guns and served to signal blockade runners coming into the river. Lamb organized the construction of a separate four-gun battery to guard the inlet. Completed in October 1864, this battery was named for the senior Confederate naval officer, Admiral Franklin Buchanan. Confederate lieutenant Robert T. Chapman soon arrived to command the Confederate naval detachment assigned to protect the inlet. Fort Fisher was a formidable position with enough artillery and infantry.

Following the successful capture of Hatteras Inlet on the outer banks of North Carolina, the combined naval and land forces of the United States took the initiative in January 1862 to invade the eastern seaboard of North Carolina. The commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Louis M. Goldsborough, cooperated with General Ambrose E. Burnside to launch an amphibious assault to capture Roanoke Island, New Bern, Washington, and Plymouth. They succeeded in achieving their goals with the exception of the destruction of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad.4

As early as May 1862, Goldsborough had plans to follow up on his success in January and attack Fort Caswell. Contrary to his wishes, he was obligated to send vessels away from the North Carolina coast to support the Peninsula campaign to take Richmond.5 Plans to attack Fort Caswell continued to be superseded by other operations. The position of the port of Wilmington 26 miles from the coast required a joint effort. The U.S. Army continued to select other objectives; therefore, the U.S. Navy was forced to do the same.

In January 1864, Welles reintroduced the idea of a joint operation against Wilmington to the Secretary of the War, Edwin Stanton, again without success.6 After the U.S. Navy’s occupation of Mobile Bay in August, Wilmington was one of the last ports of entry for blockade runners. In October 1864, Wilmington finally became the next objective for a joint amphibious operation.

Prelude

In the fall of 1864, Confederate general William “Chase” Whiting (promoted from major) was in charge of the defenses of Wilmington. After the Federal victory at Mobile Bay, Whiting predicted an imminent attack on Wilmington. In September, he noted the increasing difficulties of evading the Federal blockade. Therefore, Whiting requested support from the Confederate secretary of the navy, concerned with the lack of naval forces in position to protect the port.7

In September, the governor of North Carolina, Zebulon Vance, wrote to Lee requesting that General P.G.T. Beauregard be sent to Wilmington to replace Whiting.8 Lee passed the request to the Confederate president, but Davis had other plans: He put General Braxton Bragg in charge at Wilmington and Beauregard was sent to Georgia.

In Washington, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was also angling for a change. He wished to replace the current commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Samuel Lee, with the victor at Mobile Bay, David Farragut.9 Farragut informed Welles that he was unable to accept this command for health reasons.10 Believing that Lee was not the man for the job, and unable to appoint Farragut, Welles assigned Admiral David Porter to the command of the squadron.11 Despite his reluctance to leave the Mississippi River Squadron, Porter accepted Welles’ decision.

The Navy was ready to attack Cape Fear as early as October 1864, but General Ulysses S. Grant did not commit troops for this expedition until December. When he finally did so, it was two divisions—6,500 soldiers—under the command of General Godfrey Weitzel.12 During the planning stages, the commander of the department of Virginia and North Carolina, General Benjamin Butler, decided to take over from Weitzel, and Grant did not oppose him.

The element of surprise was important to the success of this operation.13 The Confederate army had started sending troops away from North Carolina to Georgia. However, Butler did not hurry. He hoped to avoid a siege by employing a tactic that he had seen work for the enemy during the Bermuda Hundred campaign that past May. He planned to use a naval vessel loaded with explosives to destroy the walls of Fort Fisher and ensure a quick victory. Porter had experience with joint operations, so he did not directly oppose this scheme, although admitting to Grant that it would delay their general movement.14 The success of the partnership of Butler and Porter depended on Butler and his ability to follow through on his ambitious plans.

First Battle (December 1864)

***

UNION LEADERSHIP

Rear Admiral David D. Porter, U.S. Navy (USN)

Major General Benjamin J. Butler, U.S. Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

General William H. C. Whiting, Confederate States Army (CSA)

Colonel William Lamb, CSA

***

The joint operation led by Butler and Porter seemed ill-fated from the beginning. Butler’s scheme slowed down plans to assemble at Hampton Roads. Bad weather further delayed their departure. Communications continued to break down during the move to Wilmington. Porter left with his fleet ahead of the 46 Army transports carrying Butler’s force to allow time for his slow-going ironclad monitors and a stop to replenish powder and coal. Rather than delay his departure to allow for Porter’s port call at Beaufort, Butler left soon after Porter’s fleet, so the transports arrived Cape Fear ahead of Porter. Unable to launch an assault without the Navy, Butler waited for three days. By the time that Porter and his fleet joined him, bad weather set in again.

Waiting for the storm to pass, Butler took the transports to Beaufort to coal and resupply. He notified Porter that he would return on 24 December. Before Butler’s return, Porter put their plan into motion. On the night of 23 December, the crew of Louisiana, the sidewheel steamer loaded with explosives, prepared to abandon their vessel approximately 200 yards from the beach in front of Fort Fisher. At 0140, Louisiana exploded, but it was too far from the fort to do any damage.15

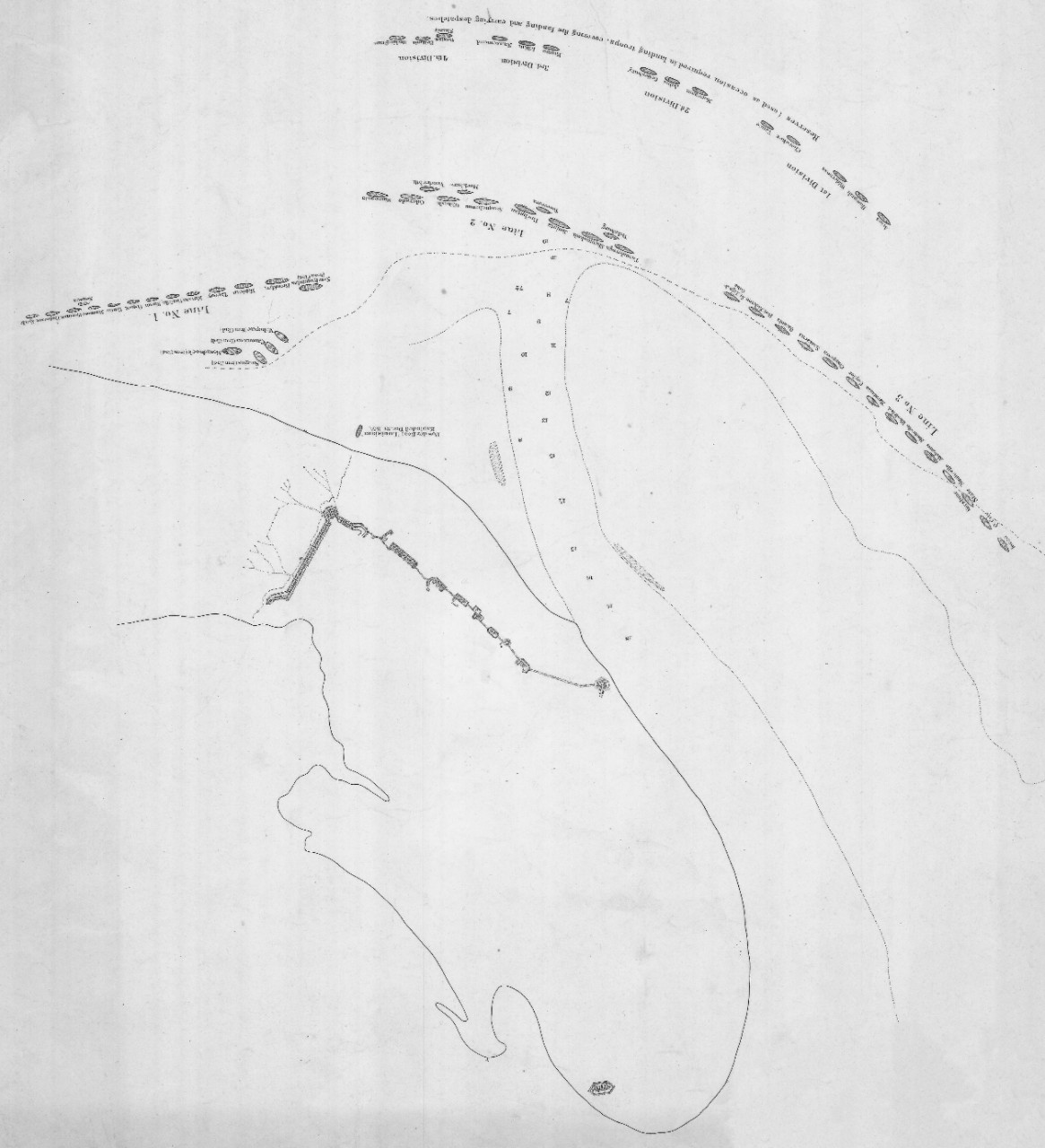

Order of attack on Fort Fisher and adjoining Confederate works. (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], Office of Coast Survey Historical Map & Chart Collection, 594-00)

At 0514 on 24 December, the 63 ships of Porter’s fleet prepared to bombard the fort. Thirty-seven ships formed in three lines of battle, end-to-end facing the enemy. The Navy’s new ironclad steamer, New Ironsides, led the monitors—Canonicus, Mahopac, Monadnock, and Saugus—and seven of the light-draft ships— Huron, Kansas, Nereus, Nyack, Pontoosuc, Pequot, and Unadilla—to form the first line, anchoring approximately one mile northeast of the fort with their broadsides facing the largest of the enemy works. Minnesota led the second line, the larger wooden ships—Colorado, Mohican, Tuscarora, Wabash, Susquehanna, Powhatan, Juniata,

Shenandoah, Ticonderoga, Vanderbilt, Mackinaw, and Brooklyn— to confront the sea face of the fort. A third line of battle formed opposite the southern end of the seaward face near the Mound Battery. This included Chippewa, Fort Jackson, Monticello, Osceola, Rhode Island, Sassacus, Santiago de Cuba, and Tacony. Porter held the rest of his fleet in reserve to provide ammunition and coal to the ships in the bombardment lines. 16

Just after midday, Porter commenced the U.S. Navy’s first bombardment of the fort and continued firing until it became too dark to aim the guns effectively. According to an account from a Confederate prisoner of war, this bombardment was enough to drive the fort’s garrison of 425 into their bombproofs.17 Colonel Lamb reported 64 casualties, three killed and 61 wounded.18 While the Confederate troops hid beneath the mounds of the fort, Lamb noted that this bombardment did little damage, with the exception of the wooden quarters of the garrison, which were set ablaze.19

Butler’s force returned too late on that first night to attempt a landing. Seaman William Hawkins, aboard Pontoosuc, watched the monitors firing through the night after the other ships had anchored out of range.20 The next morning, 25 December, the fleet resumed their barrage. Captain Oliver S. Glisson, captain of Santiago de Cuba, led the naval contingent to secure a landing area for the Federal infantry north of the fort. Captain James Alden, the captain of Brooklyn, brought the frigate as close in as possible to support Glisson’s actions. To the south, Porter wanted to cross the bar and send his shallow-draft boats into the Cape Fear River. Lieutenant Commander William B. Cushing, the captain of Malvern, led a group of sailors to take soundings at New Inlet to the south. Porter withdrew the sounding party after it became clear that the army was making no progress north of the fort.21

The timely arrival of Confederate reinforcements from Wilmington and the failure of the explosive-laden vessel caused both Weitzel and Butler to question the strength of their position. Although Weitzel was able to advance within 100 yards of the fort, he agreed with his commanding officer that they could not take the fort without a siege, for which they were unprepared.22 Butler immediately began to re-embark his soldiers.23 On 27 December, he called off the expedition and directed the transports to return to Hampton Roads. The U.S. Navy had suffered 83 casualties and the U.S. Army 12.24 Thus, the first attempt by the Federal forces to close the port of Wilmington ended.

Rather than preparing for the next blow, Confederate general Bragg celebrated the withdrawal of Federal infantry. He determined that this victory proved “the superiority of land batteries over ships of war.”25 Within two weeks of the attack on Fort Fisher, Bragg ordered the reinforcements sent to the peninsula moved back to Wilmington. This action later proved to be an error. While Butler returned to Hampton Roads, Porter remained off the coast of North Carolina preparing another attempt to capture Fort Fisher.26

Second Battle (January 1865)

***

UNION LEADERSHIP

Rear Admiral David D. Porter, U.S. Navy (USN)

Major General Benjamin J. Butler, U.S. Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

General William H. C. Whiting, Confederate States Army (CSA)

Colonel William Lamb, CSA

***

Following the fall of Savannah on 21 December 1864, Major General William T. Sherman prepared to march through the Carolinas. After the failure of U.S forces to capture Fort Fisher on 25 December, Porter quickly wrote to Sherman, clearly expressing his frustration with Butler’s decision to abandon the joint operation.27 On 29 December, Secretary of the Navy Welles wrote to Grant that the President hoped that another joint operation might be forthcoming.28 Grant promised a return of “an increased force . . . without the former commander [Butler].”29 Grant subsequently removed Butler from his command.

Unlike Butler, Porter had a good working relationship with Grant and a solid record of success in joint operations. Due to this, Welles could argue with Lincoln for Porter’s retention as commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. In early January, Porter coordinated directly with Sherman and Grant about plans for a renewal of operations against Fort Fisher. As Sherman marched north, the port of Wilmington was now more important to the U.S. Army than it had been during the first battle for Fort Fisher.

In selecting Butler’s replacement, Grant chose General Alfred Terry, one of Butler’s staff officers. Grant assigned him the same troops that had participated in the first attempt augmented with an additional brigade for a total of 8,000 soldiers.30 Both Terry and Porter had orders to cooperate fully with each other.

On 4–5 January, the second expedition to capture Fort Fisher embarked from Bermuda Landing in Virginia. Three days later, the Navy and the army transports rendezvoused off Beaufort, North Carolina. On 10 January, Porter ordered Cherokee, Gettysburg, Lilian, Monticello, and Tristram Sandy ahead of the fleet to enforce the blockade of the Cape Fear River at New Inlet.31

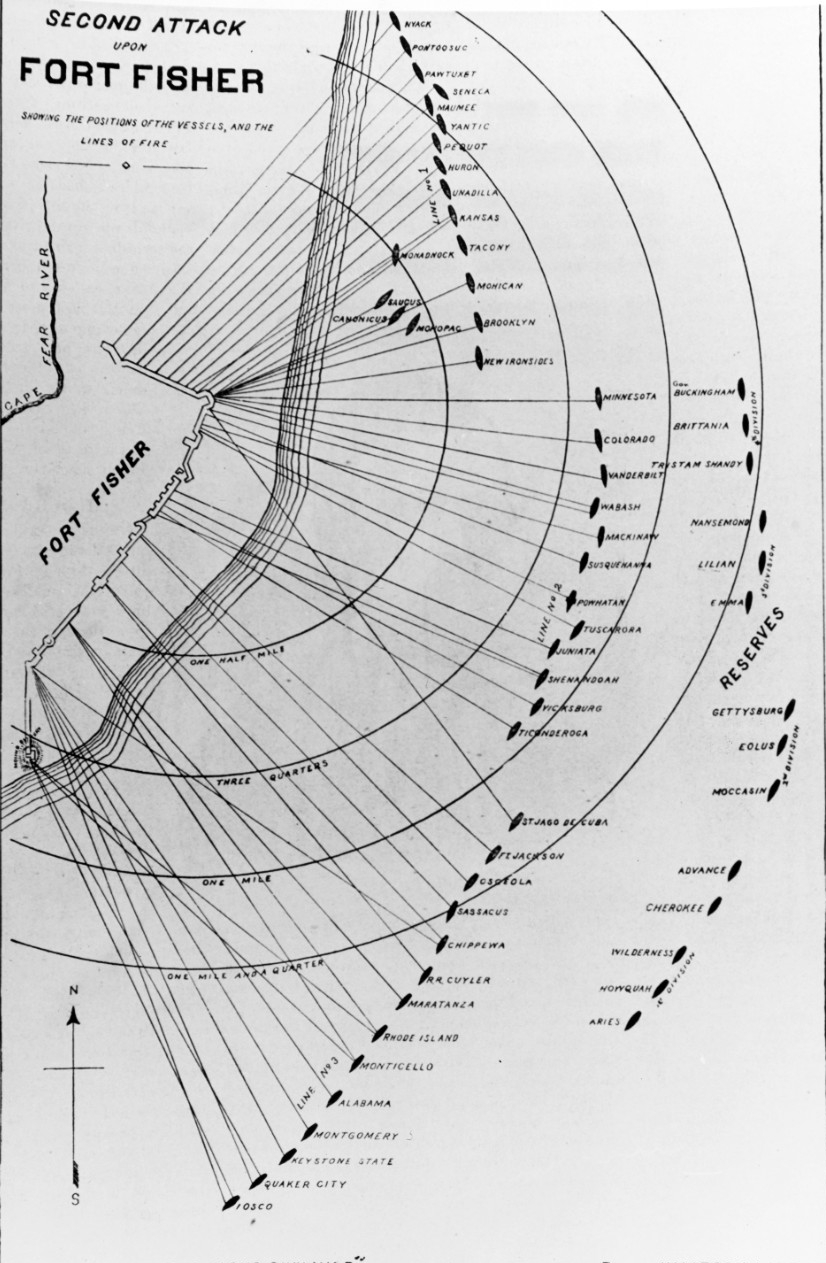

On 12 January, they headed for Fort Fisher.32 Arriving that night, Porter and Terry prepared to commence their attack the next day. On the morning of 13 January, New Ironsides led, with the other ironclads anchored in succession: Canonicus, Dictator, Mahopac, Monadnock , and Saugus. The first line of battle led with Brooklyn, followed by Huron, Kansas, Maumee, Mohican, Nereus, Nyack, Pawtuxet, Pontoosuc, Seneca, Tacony, Unadilla, and Yantic. The wooden frigate Minnesota led the second line into position: Colorado, Juniata, Powhatan, Shenandoah, Susquehanna, Ticonderoga, and Wabash. Finally, Santiago de Cuba guided the third line into position: Chippewa, Fort Jackson, Iosco, Maratanza, Montgomery, Monticello, Osceola, Quaker City, Rhode Island, and Sassacus. The 40 ships taking aim at Fort Fisher mounted more than 600 guns, not including the vessels held in reserve behind the lines of battle. The 50 cannon aboard the frigate Colorado alone were more than the number of guns guarding the walls of Fort Fisher.33

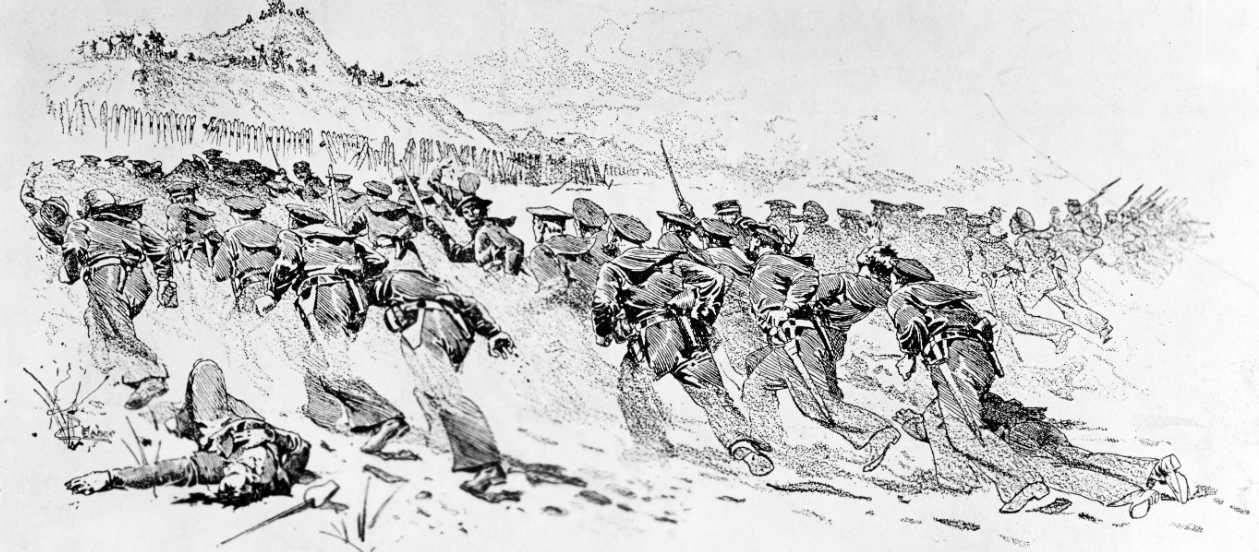

As the ships formed their lines of battle, General Terry prepared to land his infantry north of Fort Fisher immediately. At dawn on 13 January, 8,000 Federal soldiers landed above the fort as the Navy began its bombardment. Porter was determined to learn from past experience, giving orders to aim at the parapets or traverses protecting the fort’s defenders and the gun emplacements rather than the flagstaffs.34 After two days of heavy fire from the Navy, the combined Federal forces prepared for a tiered attack against the land face of the fort. Porter committed sailors, lightly armed with cutlasses and revolvers, to land and “board the fort on the run in a seaman-like way.”35 They were accompanied by marines armed with rifles and bayonets. Porter intended the marines to serve as sharpshooters while the sailors advanced on the left flank of the Federal line toward the northeast bastion (at the intersection of the two faces of the fort).

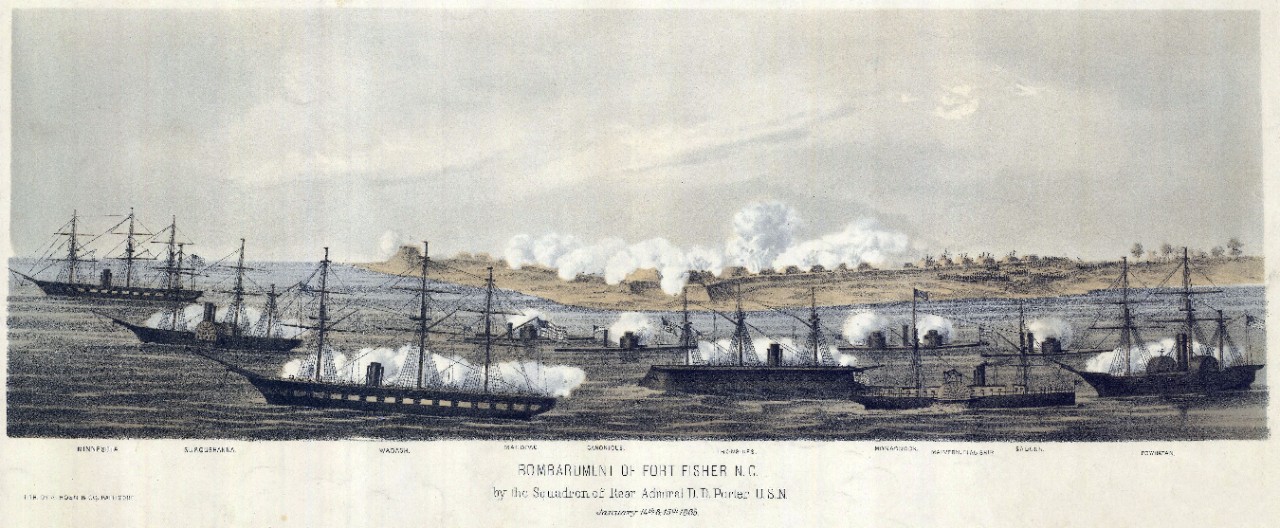

Bombardment of Fort Fisher N.C. by Squadron of Read Admiral D.D. Porter U.S.N. January 14th & 15th 1865, c. 1934, lithograph, A. Hoen and Co., Baltimore, MD. Ships pictured from left to right include: Minnesota, Susquehanna, Wabash, Mahopac, Canonicus, Ironsides, Monadnock, Malvern (Flagship), Saugus, and Powhatan. (NOAA, 3014-00-1865)

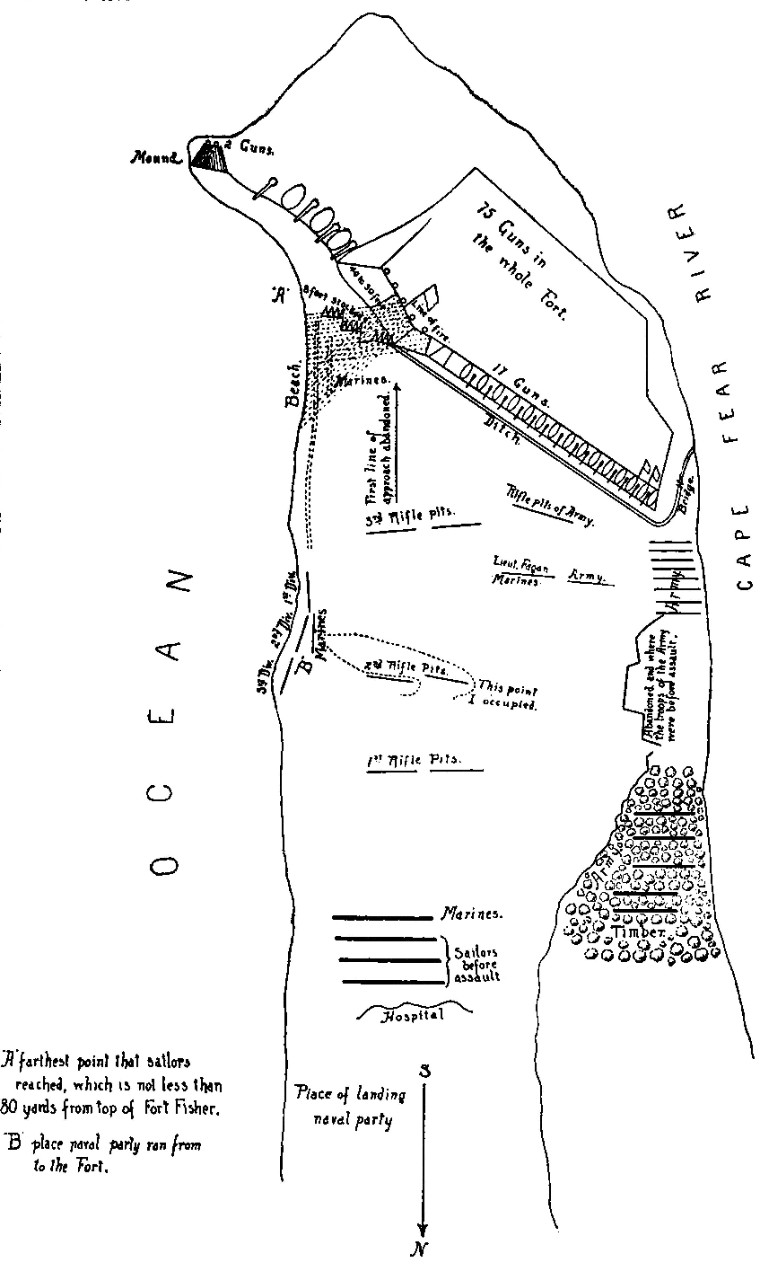

At 0900 on 15 January, Admiral Porter put ashore 2,261 sailors and marines from 20 different ships to attack the sea (southeast) face of the fort while the army prepared to attack the land face.36 Lieutenant Samuel W. Preston led an advanced detachment equipped with shovels to throw up breastworks within 600 yards of the fort (less than a half mile) before moving closer to prepare for the full assault.37 Porter’s fleet captain, Lieutenant Commander K. Randolph Breese, led the naval brigade. At 1500, the ships shifted the direction of their fire to the upper batteries away from the naval column and their whistles signaled the beginning of the assault.38

Hand-drawn map from U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 11 (Washington: GPO, 1900), 579.

Repulsed with heavy casualties, the naval brigade failed to reach the fort, but their movement successfully distracted the fort’s garrison from the army’s attack on the land face.39 Of the U.S. Navy sailors put ashore, 393 were killed, wounded, or missing after the assault.40 The sacrifice of these sailors allowed the army to breach the walls of the fort. By 1800, Federal soldiers had breached the walls of the fort. Before 2200, the fort was in possession of the Federal forces.

Inside the fort, General Whiting sent a final plea to General Bragg in Wilmington for reinforcements.41 Bragg’s only response was to send General Alfred Colquitt to replace Whiting. This officer failed to reach the fort arriving in time to witness the Confederate retreat toward Battery Buchanan.42The Confederate naval contingent at the battery had already retreated across the river to Battery Lamb.43 When Federal infantry caught up with them, General Terry accepted the formal surrender of the fort from the wounded General Whiting.

Aftermath

The first battle of Fort Fisher was the most concentrated naval bombardment of the war. The fleet fired 20,271 projectiles into the fort during the first battle. Another 19,682 were fired during the second battle. In total, the U.S. Navy expended 39,953 projectiles at the fort. After Fort Fisher’s capture, Porter proceeded to put vessels over the bar and into the Cape Fear River. He declared the port of Wilmington to be “hermetically sealed against blockade runners.”44

The second joint operation to capture Fort Fisher was a success. The commanders had successfully accomplished their goals and both seemed pleased with the way in which the operation had played out. Admiral Porter praised General Terry and the U.S. Army for their cooperation.45 Terry was grateful for the assistance of the U.S. Navy and the Marine Corps in both the bombardment preceding the assault and their participation in the assault itself.46

Five weeks after the fall of Fort Fisher, the Federal army occupied the city of Wilmington. This occupation ended the trickle of supplies coming along the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad to the Army of Northern Virginia. The fall of Wilmington contributed directly to this army’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

“The Battle Between the Battles of Fort Fisher,” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, 7 January 2015.

“Remembering the Sailors and Marines Sacrificed at Fort Fisher,” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, 31 January 2015.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

First Assault on Fort Fisher: Ben Butler and the Powder Boat Scheme, Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia.

“The Fort,” North Carolina Historic Sites.

Fort Fisher Battle Facts and Summary, American Battlefield Trust.

Wilmington: The Last Open Port on the Confederate Coast, Emerging Civil War.

David W. Kummer, U.S. Marines in Battle: Fort Fisher, December 1864–January 1865. Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps History Division, 2012 [PDF].

FURTHER READING

Fonvielle, Chris E. The Wilmington Campaign: Last Rays of Departing Hope. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Co., 1997.

Gragg, Rod. Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort Fisher. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1991.

Hardy, Michael C. North Carolina in the Civil War. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011.

Moore, Mark A. Moore’s Historical Guide to the Wilmington Campaign and the Battles for Fort Fisher. Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing, 1999.

Symonds, Craig. “The Navy's Evolutionary War.” Naval History Magazine, Vol. 25, no. 2 (April 2011).

***

NOTES

[1] United States War Department, The War Of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1880), 477.

[2] ORA, 1, 1:477.

[3] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 5 (Washington: GPO, 1897), 753.

[4] ORN, ser. 1,6 (1897), 508

[5] L. M. Goldsborough to G. V. Fox, 21 May 1862, in Robert M. Thompson and Richard Wainwright, ed., Correspondence of Gustavus Vasa Fox; Assistant Secretary of the Navy, 1861–1865, vol. 1 (New York: Naval History Society, 1920), 271–74. Goldsborough was replaced as commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron in September 1862.

[6] ORA, 1,32 (1891), 326; ORA, 1,32:356.

[7] ORN, 1, 10 (1900), 751.

[8] ORA, 1, 42, pt. 2, 1235.

[9] Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles; Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, vol. 2 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 127.

[10] ORN, 1, 21 (1906), 690.

[11] Diary of Gideon Welles, 2:146–47; ORN, 1, 21:657.

[12] ORA, 1, 34 (1891), pt. 1, 40.

[13] ORA, 1, 42, pt. 1, 970; ORN, 1, 10:751.

[14] ORN, 1, 11:268; ORA, 1, 42, pt. 3, 750.

[15] Read more about the this scheme (North Carolina Historic Sites).

[16] ORN, 1, 11:288–89, 303–304; Also see Mark L. Evans, Minnesota I (Frigate), Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed 22 November 2022.

[17] A bombproof is a structure designed to protect its occupants against artillery fire. In the case of Fort Fisher, these were dugouts below mounds of earth and sand.

[18] Lamb, Colonel Lamb’s Story, 20; ORA, 1, 42, pt. 1 (1893), 1004.

[19] Lamb, Colonel Lamb’s Story, 16–17.

[20] For a brief firsthand account from William Hawkins aboard Pontoosuc, read the transcription of the second volume of his diary available for download from the Navy Department Library here.

[21] ORN, 1, 11:258.

[22] ORA, 1, 42, pt. 3, 1075–76.

[23] ORA, 1, 42, pt. 3, 1076.

[24] Mark A. Moore, Moore’s Historical Guide to the Wilmington Campaign and the Battles for Fort Fisher (Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing, 1999), 33; ORN, 1, 11:371.

[25] ORA, 1, 42, pt. 1, 999.

[26] Grant removed Butler from command on 8 January 1865.

[27] ORN, 1, 11:388–89.

[28] ORN, 1, 11:391–92.

[29] ORN, 1, 11:394.

[30] ORN, 1, 11:405.

[31] ORN, 1, 11:421.

[32] ORA, 1, 46:393.

[33] Mark A. Moore, The Wilmington Campaign and the Battles of Fort Fisher, 163.

[34] ORN, 1, 11:426–27. A parapet is a work constructed of earth, sand, or masonry that forms a protective wall, similar to a rampart. A traverse is a smaller rampart built perpendicularly to the main fortification to protect against enfilade (flanking) fire.

[35] ORN, 1, 11:427.

[36] “Remembering the Sailors and Marines Sacrificed at Fort Fisher,” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, 31 January 2015.

[37] ORN, 1, 11:446.

[38] ORN, 1, 11:439.

[39] ORN, 1, 11:586.

[40] ORN, 1, 11:444; “Remembering the Sailors and Marines Sacrificed at Fort Fisher,” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, 31 January 2015.

[41] ORA, 1, 46, pt. 1, sec. 1, 434.

[42] ORA, 1, 46, pt. 1, sec. 1, 434.

[43] R. Thomas Campbell, ed., Voices of the Confederate Navy: Articles, Letters, Reports, and Reminiscences (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), 56.

[44] ORN, 1, 11:441.

[45] ORN, 1, 11:444.

[46] ORA, 1, 46, pt. 1, sec. 1, 400.