Tucker I (Destroyer No. 57)

1916-1936

Both the first and second ships named Tucker honored Samuel Tucker, born on 1 November 1747 in Marblehead, Mass., who began his naval career in the spring of 1760 as a cabin boy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony warship, King George. He subsequently sought his fortune in the merchant service, rising to command of a ship in July 1774. Tucker was in England at the outbreak of the American War for Independence, but returned to Massachusetts in the autumn of 1775.

Upon his return to the colonies, Tucker was selected by General George Washington to command a small flotilla of armed schooners which he had purchased and fitted out to prey on the shipping which was bringing supplies from England to America to support British troops in the colonies. Tucker also served as commanding officer of the schooner Franklin.

In that schooner and later in schooner Hancock, Tucker swept the seas around Boston and off the Massachusetts coast, taking many prizes in the year 1776. His first, taken jointly with the schooner Lee, came on 29 February, when the two Continental ships cornered the 300-ton Henry and Esther, bound for Boston laden with wood from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In April 1776, in Hancock, Tucker sighted two supply brigs making for Boston. Standing in to the harbor, very near to the protecting cannon of British warships anchored in the roadstead, he soon captured brigs Jane and William, out of Ireland. Tucker brazenly sailed up and took both from beneath the very noses of the British Navy, escaping with the two ships and their valuable cargoes of foodstuffs and other items needed by the Continental Army.

Because of his distinguished record, Tucker was given command of the new Continental Navy frigate Boston in March 1777. On 21 May, Boston and sister frigate Hancock set sail from Boston to raid the King's commerce on the high seas. Cruising in the North Atlantic, eight days out of their home port, the raiders captured a small brig laden with cordage and duck.

On 30 May, they sighted a convoy of troopships escorted by the 64-gun HMS Somerset, which soon set course to engage Manley's Hancock. Sizing up the situation in his experienced mariner's eye, Tucker bent on sail to go after the transports to wreak havoc among them. At that point, Somerset's commanding officer decided not to engage Hancock, since his primary mission was to protect the transports. Thus, Hancock escaped nearly certain devastation at the hands of the 64-gun Britisher. Tucker's timely action and good shiphandling were undoubtedly major factors in the Briton's decision.

On 7 June, Boston and Hancock engaged HMS Fox and made her a prize after a heated battle. One month later, on 7 and 8 July 1777, HMS Flora, HMS Rainbow, and HMS Victor attacked the three Continental ships and took Hancock and Fox. Only Boston escaped.

For the remainder of 1777, Tucker, in Boston, carried out commerce-raiding forays in the North Atlantic and off the northeast coasts before being selected for a special mission. On 13 February 1778, Capt. Samuel Tucker was rowed ashore to Braintree, Mass., where he soon sat down for a hasty and early meal with the family of John Adams. Soon, Adams, the newly appointed minister to France, and his son, John Quincy, were taken out to Boston and lodged on board as preparations for heading out to sea were completed.

Encountering heavy seas and wind halfway across the Atlantic, Boston was nearly dismasted in a gale. On another occasion, three British warships gave chase to the solitary Continental frigate and her distinguished passenger. The unpleasant surroundings of a dank and dismal English prison were not relished by anyone, least of all Adams, who would have been considered a traitor to the crown. After having avoiding contact with British ships as much as possible, Tucker was finally forced to fight.

Encountering a British privateer, Tucker maneuvered Boston to cross the enemy's "T." With devastating effect, Boston's guns thundered and sent shot down the length of the Britisher, and soon, the Briton struck her colors. Arriving safely at Bordeaux on 1 April, Adams would have stories to tell in future days about his eventful voyage with Samuel Tucker.

Cruising in European waters from the spring of 1778 until the fall of that year, Tucker took four more prizes before returning to Portsmouth, N.H., on 15 October. In 1779, two cruises in the North Atlantic netted nine prizes for Tucker and his mariners before orders sent Boston to Charleston, S.C., to help defend that port against the British onslaught.

On 11 May 1780, Charleston surrendered, after a siege, and the warships in harbor were captured, along with most of their officers and men. Tucker was among the prisoners but would not remain so for long, as he received parole on 20 May and was exchanged for British Capt. Wardlaw, whom Tucker had captured when Boston took HMS Thorn in September 1779.

On 11 January 1781, Tucker assumed command of Thorn, now a privateer. After taking seven prizes, he was again captured in an engagement with HMS Hind off the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. He and his crew were treated kindly and taken to Prince Edward Island. One day, having had permission to go to Halifax, Tucker escaped and made his way to Boston. In an era where chivalry in war was still very much alive, Tucker wrote a letter of apology to the British garrison commander for his escape. At his own request, Tucker was paroled.

When the war had ended and independence had been secured for the fledgling United States, Tucker received hearty thanks from Congress. During the years following the establishment of peace, the old mariner from Marblehead sailed packets from America to Bremen, Germany, until he retired to farming, in Maine, in 1792.

Yet, when the young United States once again went to war with Britain in the War of 1812, Samuel Tucker returned to active service, commanding a schooner which protected the coast of Maine from British privateers. In 1813, he captured the British privateer Crown in a short, sharp engagement, putting an end to the harassment of Maine coastal trade which had been posed by the Briton.

Changing his residence to Massachusetts, Tucker settled down once again to a life of farming. In 1823, he was awarded a small pension, retroactive to 1818.

After holding positions of public trust in his home state of Massachusetts and having lived a life of adventure on the high seas, Samuel Tucker died at the age of 86 in Bremen, Maine, on 10 March 1833.

I

(Destroyer No. 57: displacement 1,090; length 315'3", beam 29'10"; draft 9'4½"; speed 29.56 knots; complement 101; armament 4 4-inch, 8 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Tucker)

The first Tucker (Destroyer No. 57) was laid down on 9 November 1914 at Quincy, Mass., by the Fore River Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 4 May 1915; and sponsored by Mrs. Mary Hinds Garty, great-great-granddaughter of Captain Samuel Tucker.

Tucker was commissioned on 11 April 1916 at the Boston (Mass.) Navy Yard, Lt. (j.g.) Frank Slingluff, Jr., in temporary command; Lt. Cmdr. Benyaurd B. Wygant assumed command 13 days later. Following commissioning, the new destroyer commenced further trials off the east coast, working up, before reporting to Division 8, Destroyer Force, Atlantic Fleet. While World War I raged in Europe, Tucker and units of the fleet carried out exercises and maneuvers in southern and Cuban waters into the spring of 1917.

On 2 April 1917, Tucker sailed to escort the gunboat Dolphin to St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, that had recently been acquired by the United States. En route, she received word of the United States’ declaration of war on the Central Powers on 6 April. The following day, the two ships reached their destination and Rear Adm. James H. Oliver began service as the first U.S. Governor General of the islands.

While Dolphin remained at St. Thomas, Tucker steamed to join the Atlantic Fleet at its anchorage in the York River, making arrival there on 11 April. She performed various duties in the Chesapeake, serving as a dispatch boat, convoying arriving French cruisers and patrolling for U-boats. On 24 April, she convoyed the French auxiliary cruiser Lorraine to New York where the destroyer stayed to conduct patrols in surrounding waters, after which she received orders to proceed to the Boston Navy Yard to fit-out for distant service, on 29 April.

The immediate and pressing need for submarine hunters led to the deployment of U.S. destroyers to Queenstown [Cobh], Ireland, beginning with the departure of six ships on 24 April 1917 under Cmdr. Joseph K. Taussig, Jr. Later, Tucker, in company with Rowan (Destroyer No. 64), Cassin (Destroyer No. 43), Ericsson (Destroyer No. 56), Winslow (Destroyer No. 53), and Jacob Jones (Destroyer No. 61) cleared Boston on 7 May in the second contingent of U.S. destroyers designated to operate in conjunction with British surface forces patrolling off the Irish coast.

After arriving at Queenstown on 17 May 1917, the Americans had little time to rest. Ship’s force and British dockworkers prepared the vessel for her mission, removing mine laying tracks and minesweeping gear and installing depth charges and their associated equipment.

On her very first day of patrol, 21 May 1917, Tucker claimed an engagement with two enemy submarines simultaneously. She opened fire with her guns but both submerged and escaped. Less than a month later, on 12 June, she rescued 47 survivors from the Queenstown-bound British steamer Polyxena, which had been torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-95 (Kapitänleutnant Athalwin Prinz, commanding). Since submarines were nearly impossible to detect below the surface, destroyers attacked any potential indication of a submerged vessel including oil slicks or disturbances in the water.

During the morning watch on 5 July 1917, Tucker spotted a large oil slick, which Lt. Cmdr. Wygant estimated contained hundreds of gallons of oil. The destroyer followed it to its source, a spot with bubbles of fuel rising from below the surface. She dropped two depth charges, one large and the other a smaller U.S. depth charge. The latter malfunctioned and, despite its purpose, floated precariously on the water. Bluejackets hurriedly sank the wayward weapon with rifle fire. The large depth charge functioned as designed and exploded, bringing more oil to the surface. After the attack, officers did not report any indication that the oil originated from a submerged vessel.

Tucker was escorting a pair of oil tankers on 19 July 1917 when lookouts spotted the British steamer Blakemore firing her after gun. The destroyer closed on the vessel which sent a signal that she had seen a submarine. The destroyer circled the embattled merchantman, dropping a depth charge on the spot where Blakemore indicated that the submarine submerged. The crew did not witness any results and the submarine did not reappear. She stood by for approximately one hour before continuing with her convoy.

On the last day of July 1917, a sailor on watch spotted a suspicious object in the water on the port bow at 7:00 p.m. Tucker closed and opened fire with her no. 1 gun at 4,000 yards, getting off four shots. Approaching her target, the sailors at their guns eased up, recognizing their “adversary” as nothing more than floating spar. Sailors commonly misidentified debris, oceanic features, or even sea life as submarines in the Western approaches. Such mistakes proved inevitable where a ship’s safety depended on a lookout detecting the slightest disturbance at great distances in seas sometimes cluttered with floating debris.

On the following day [1 August 1917], Tucker located a lifeboat filled with 39 survivors from the British passenger steamer Karina, which had been torpedoed and sunk on 1 August by UC-75 (Oberleutnant zur See Johannes Lohs, who would ultimately be credited with sinking 77 ships and damaging 16). She steamed around the wreckage attempting to recover the remains of reported casualties before transferring them to Conyngham (Destroyer No. 58) standing into Bantry Bay, Ireland, for fresh water.

The watch spotted a floating mine at 8:00 p.m. on 20 August 1917 while escorting two merchant vessels near Queenstown. Tucker rerouted the convoy and bluejackets again shouldered rifles and took aim at the threat. Gunners on the number one gun joined in the barrage. After several hits the mine disappeared without exploding and Tucker continued on with her convoy.

On 3 September 1917, lookouts on board Tucker spotted a torpedo wake presumably fired at the destroyer. Tucker changed course and closed on the origin of the wake, dropping a depth charge after reaching the spot. She observed no results and did not see the submarine again. From 13-23 September, she underwent repairs at the Cammell-Laird yard, then early the following month, rescued 13 sailors from the British steamer Richard de Larrinaga, including two men clinging precariously to a floating piece of wreckage, after U-57 (Kapitänleutnant Carl-Siegfried Ritter von Georg) torpedoed her off Ballycottin Island, Ireland, on 8 October. She circled for an hour while searching for the remaining 35 crewmembers but could not locate them. The destroyer transferred the survivors to the British tug Francis Bates and continued her patrol.

Tucker collided with Rowan on 10 November 1917 and suffered damage. She continued with her convoy but steamed to Brest, France, when it dispersed. There her damaged bow was shored up before she returned to Queenstown on 13 November. Drydocked at Rushbrook, Ireland (16-23 November) she received further work at the Iron Works in Passage West, Ireland (24 November-1 December).

Tucker again found herself in an unenviable position on 9 December 1917 when her rudder jammed hard right, sending the vessel in circles for up to ten hours while crewmembers struggled to gain control. To add to the discomfort and danger, the ship rolled heavily. Her resourceful crew eventually settled on manually detaching the rudder and through various improvisational means navigated the ship back to port on her own power. Back at sea on 20 December, she twice spotted and dropped depth charges on a submarine without witnessing any results.

On 1 February 1918, Lt. Cmdr. Walter H. Lassing, her new commanding officer, was in the chart house at 3:17 p.m. when a lookout sighted the conning tower of a submarine three points forward on the port beam. As the commander rushed to the bridge, Lt. (j.g.) Leon S. Fiske on the bridge ordered the rudder put over hard left, ordered the guns manned and rang up full speed. The destroyer closed through heavy seas that prohibited the firing of her forward gun. Unable to fire, she prepared to ram her adversary. Tucker closed to within 500 yards before the submarine spotted her and executed a crash dive. After the U-boat submerged, gunners dropped a depth charge but did not witness any results. The destroyer took minor damage by charging headlong into the heavy sea. Two crewmen also suffered broken bones from the jostling. Less than a fortnight later, she dropped a charge on an oil slick on 13 February with no results.

Tucker was entering Cammell-Laird yards at Birkenhead, England, for refit on 25 April 1918. At 11:00 p.m., tugs were assisting the destroyer into dry dock when they lost control. The warship rammed the dock, bending the stem and causing damage to the starboard side. The accident extended the scheduled refit, and she steamed toward Queenstown on 11 May.

On 28 May 1918, Duncan (Destroyer No. 46) spotted a submarine and dropped depth charges. Tucker closed on the site of the attack and dropped fourteen charges of her own including two from her Y-gun depth charge projector. The gunners worked in waist deep sea to unload the charges from the stern track. The British admiralty was skeptical of the encounter, ruling that there was no evidence of a U-boat in the vicinity.

By the early summer of 1918, as American forces poured into the war on the Western Front and swelled in numbers on the continent of Europe, the need for escorts to convoy the ships that bore the men and materiel grew apace. Thus, American destroyers were progressively transferred to the eastern Atlantic to augment the escort forces already operating in that war zone.

In June 1918, Tucker joined the escorts working out of Brest. On 7 August, while steaming out to meet the inbound convoy H.B.7, she received word that the group’s escort, the French armored cruiser Dupetit-thouars, had been torpedoed and sunk by what proved to be U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen). At the beginning of the first dog watch on the following day, lookouts sighted several sailboats and rafts that contained the entire crew of the French warship. The destroyer took on survivors with other U.S. ships, receiving 122 men and 5 officers. Tucker’s efforts, and those of the five other American destroyers who were also present, were rewarded by a commendation from the Prefet Maritime, on behalf of the French Ministry of Marine.

While taking part in the campaign to eradicate the German submarine menace preying upon Allied shipping, Tucker obtained her share of the submarine hunting the day after assisting in the rescue of Dupetit-thouars’ crew. The French sailors now on board Tucker kept the American crew on edge, constantly claiming to sight an enemy submarine. She saw a large U-boat at 10:07 a.m., which immediately submerged. At 3:00 p.m. on 9 August 1918, the quartermaster on watch spotted a periscope only 800 yards distant on the port bow. The destroyer’s adversary immediately spotted her and submerged. Tucker closed on the spot and crossed the submarines path. She dropped a barrage of fifteen depth charges. Crew members spotted the submarine come to the surface 1,000 yards distant on the starboard beam, likely forced to do so by the intense barrage. As the French survivors cheered, gun crews opened fire and the destroyer swung to pursue the U-boat. The bridge claimed one hit on the submarine’s bow which they believed stopped the vessel. The U-boat submerged again and Tucker passed over her, noting that below the surface she was inclined 30 degrees and listing. The destroyer dropped three more charges but did not witness any results. She lowered a K-tube -- a listening instrument installed in destroyers purported to be able to hear underwater noises -- but the operator was unable to hear the submarine. The commanding officer concluded that the submarine sank below the range of the device.

American officers at Brest claimed that the alleged submarine was entirely destroyed and Tucker received authorization to paint a white star on her forward funnel to indicate successfully putting an enemy vessel out of action. Later in August, however, Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, expressed skepticism, claiming that his counterparts in the British Admiralty did not have information suggesting a submarine nearby. He also criticized Tucker for dropping only two depth charges when the submarine was sighted submerged and only circling the vicinity for one more hour. On 4 October 1918, Sims wrote to the Secretary of the Navy stripping the destroyer of the victory because there was no indication of submarines in the vicinity in Admiralty records.

On 11 November 1918, the Armistice was signed, and hostilities ceased. As American forces withdrew from Europe and headed home to the U.S., Tucker carried passengers and mail between French and British ports. Departing from Brest for the last time on 16 December 1918, she headed for Boston, Mass., and a period of repairs in the navy yard.

In July 1919, Tucker cleared Boston and cruised along the coastlines of Massachusetts and Maine, engaged in recruiting duty. In October 1919, she was placed in reserve in Philadelphia, Pa., where she remained until placed out of commission on 16 May 1921 and transferred to Charleston, S. C., for repairs. On 17 July 1920, Tucker was redesignated from Destroyer No. 57 to DD-57.

By 1924, the passage of the 18th Amendment, Prohibition, had spawned a thriving traffic in smuggling alcoholic beverages. The Coast Guard’s small fleet, charged with stopping the illegal maritime importation of liquor, was unequal to the task. Consequently, President Calvin Coolidge proposed to increase that fleet with 20 of the Navy’s inactive destroyers, and Congress authorized the necessary funds on 2 April 1924. Adapting the vessels to law enforcement service was thought to be less costly than building new ships. In the end, the rehabilitation of the vessels became a saga in itself because of the exceedingly poor condition of many of the war-weary destroyers. This initial group still needed bolstering and was augmented with a further group of five destroyers. Tucker was among this latter contingent. She was transferred to the Treasury Department for service with the Coast Guard at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 25 March 1926. She then underwent a period of overhaul in order to bring her up to seaworthiness and operational capability for her law enforcement mission. Additionally, the destroyers were by far the largest and most sophisticated vessels ever operated by the Coast Guard; trained crewmen were nearly non-existent. As a result, Congress subsequently authorized hundreds of new enlisted billets. It was these inexperienced recruits that generally made up the destroyer crews.

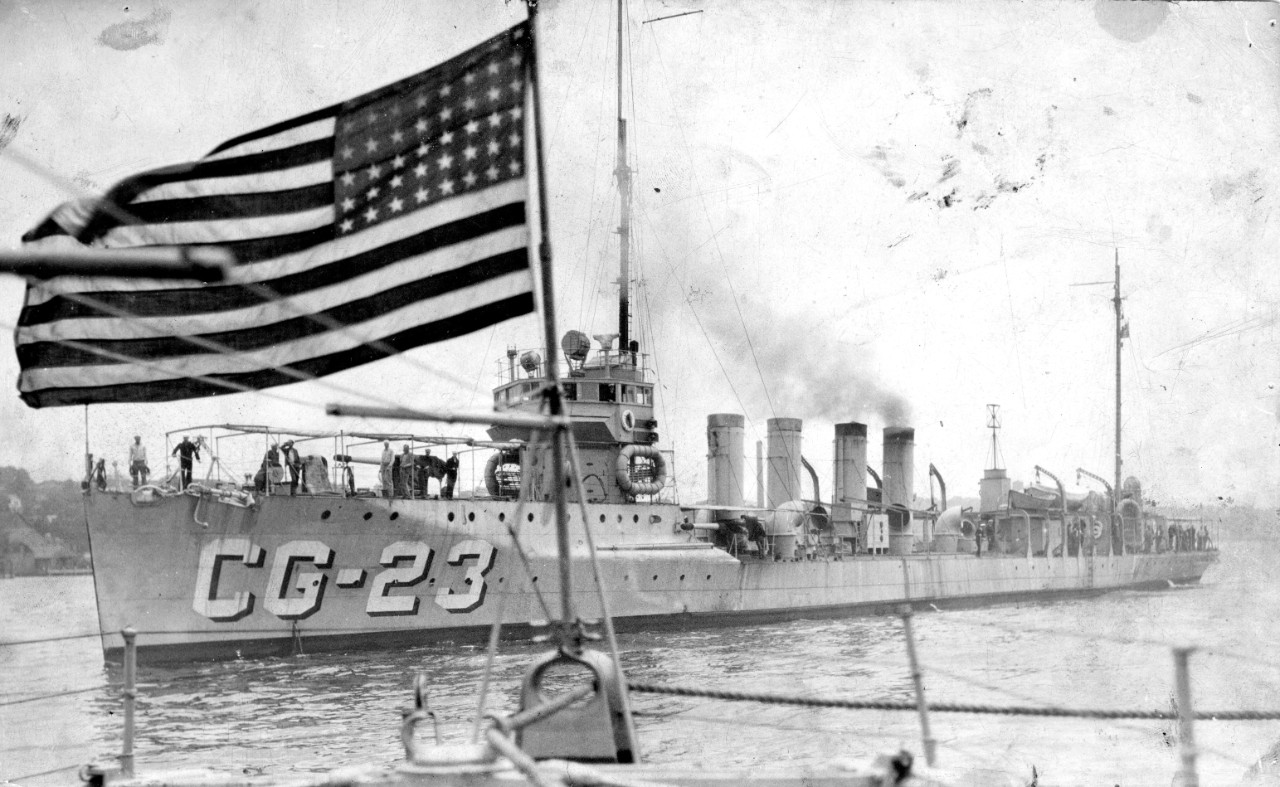

While still undergoing her yard work, she received orders on 22 May 1926 to report to New London, Conn., for duty with Division Four. She departed the yard and after conducting a shakedown en route, arrived at New London on 24 September. Retaining her name, but re-designated CG-23, Tucker was placed into commission at New London on 29 September, Lt. Cmdr. Russell R. Waesche, USCG, in command.

Shortly after being placed in commission, Tucker received orders on 2 October 1926 designating her as flagship for Division Four with Waesche to serve as division commander; those orders went into effect on 15 October. While Tucker was capable of well over 25 knots, seemingly an advantage in the interdicting of rumrunners, she and her fellow destroyers were easily outmaneuvered by smaller vessels. As a result, the destroyers had designated patrol sectors which picketed the larger supply ships (“mother ships”) on Rum Row in order to prevent them from off-loading their illicit cargo onto the smaller, speedier contact boats that ran the liquor into shore.

With the new year, Tucker was excused from participating in the battle practices for Gunnery Year 1926-1927. Instead she continued to train and qualify her crew and to patrol her designated sectors. On 24 October 1927, Tucker transferred to Division One, Destroyer Force, and was dispatched to patrol the waters off Florida the interdict the flow of illegal alcohol from the British-ruled Bahamas. On 11 January, Tucker seized the motorboat V-8721. She towed the seizure into the Fort Lauderdale CG Station and turned her over to the custody of the cutter Tampa. Tucker received orders back to New London, on 31 March 1928. She would operate from her home station through the rest of 1928.

Tucker departed New London on 4 February 1929, bound for the Gunnery Year 1928-1929 target practices at Charleston, S.C. En route she touched at Parris Island, S.C., on 6 February, and later arrived at Charleston. With 24 destroyers competing, Tucker stood 22nd overall. After conducting her training, she stood out of Charleston on 6 March bound for New London and arrived two days later. The destroyer spent the remainder of the year conducting her patrols with in port and maintenance periods interspersed.

The onset of 1930 saw Tucker again depart New London bound for target practice in Southern waters. Leaving on 6 February, she arrived on the new training ground at St. Petersburg, Fla., on 12 February. The Gunnery Year 1929-1930 exercises saw Tucker make remarkable improvement in her marksmanship. Standing atop the table with her long-range battle practice, her overall position was undone by an 18th place finish among 19 destroyers in the short-range practice, to stand 3rd overall. With the end of the exercises, Tucker returned to New London and her regular patrolling operations on 11 March. While on patrol on 1 November, Tucker seized the British motor vessel Mazel Tov out of Halifax, N.S. Having taken the rumrunner in tow, she arrived at Providence, R.I., the next day. Tucker delivered the vessel and her illegal cargo of 403 cases of liquor to the U.S. attorney and the Collector of Customs for prosecution on 3 November.

Tucker departed New London on 6 February 1931 again bound for target practice at St. Petersburg. Hopeful for a like result in Gunnery Year 1930-1931, the destroyer arrived on the 10th. Tucker’s gunners remained. Under the direction of Lt. Charles W. Lawson, the ship’s gunnery officer, she improved her overall standing to 2nd among the 13 destroyers in the annual competition. Having again demonstrated her gunnery efficiency, Tucker departed St. Petersburg for New London on 15 March and returned home on the 27th.

Tucker, unfortunately, could not sustain her previous levels of achievement in the target practices for Gunnery Year 1931-1932. Having left New London on 11 January 1932, she arrived at St. Petersburg on 15 January. Standing 12th in the short-range battle practice and 10th in the long-range, Tucker saw her overall standing drop to 10th of 13. With this disappointing showing after two previous stellar performances, she departed for New London on 17 February. Arriving back at her home port on the 21st, Tucker resumed her operational routine of interdiction patrols, maintenance availabilities, and time in port.

Tucker’s grueling anti-smuggling duties eventually wore on her and over time, she became increasingly unfit as demonstrated by her having to miss her patrol of 4-9 December 1932 for repairs. To that effect, Coast Guard Headquarters issued a memorandum on 10 February 1933, stating that the 1,000 ton destroyers were to be decommissioned during 1935.

On 4 April 1933, the greatest disaster that aeronautics had experienced up to that time occurred off the New Jersey coast, when the rigid airship Akron (ZRS-4) crashed in a storm and carried 73 men, including Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, to their deaths. Tucker received word of the crash and sped to the scene. Upon arrival, she found that the German motor ship Phoebus had pulled four men from the sea -- one of whom died shortly after being rescued. The survivors were transferred to Tucker and were disembarked at the New York Navy Yard.

Tucker’s participation in the Akron tragedy proved to be her last significant service, as the approaching ratification of the 21st Amendment that ended Prohibition, however, foreshadowed the Coast Guard no longer having to employ aging destroyers as patrol vessels. To that end, Tucker arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 26 May 1933 and was decommissioned, along with Davis (CG-21), Shaw (CG-22), McDougal (CG-6), Cassin (CG-1), and Conyngham (CG-2), on 5 June. The Coast Guard returned Tucker to the custody of the Navy Department on 30 June 1933.

Tucker’s name was cancelled on 1 November 1933 to free the name for a new generation destroyer, DD-374, and, thereafter, the old destroyer was known by her identification number DD-57. For a time, she served as a Sea Scout training ship, docked at Sandy Hook, N.J., until August 1936 when the Navy was forced to recall and dispose of the destroyer under obligations of the London Naval Treaty.

Stricken from the Navy List on 24 October 1936, DD-57 was sold on 10 December 1936 to the Northern Metal Co. of Philadelphia, along with ex-Eagle 46 (PE-46), and reduced to a hulk two days before Christmas of 1936.

Robert J. Cressman, S. Matthew Cheser, and Christopher B. Havern, Sr.

20 May 2017