Revenge III (Schooner)

1806–1811

A noun describing the act of one entity inflicting punishment upon another in response to an injury, perceived or actual in nature.

III

(Schooner: length 70; complement 43; armament 12 6-pounders)

Ranger was a schooner built in 1805 at William Price’s shipyard at Fell’s Point in Baltimore, Md. Price was one of several well-known shipbuilders in the area recognized for making letter of mark schooners. In the months following her completion she sailed out of Baltimore, but her original owner remains unknown. Her service in the United States Navy commenced in December 1806 when she was purchased by Master Cmdt. John Shaw in New Orleans, La., and renamed Revenge; Lt. Cmdt. Benjamin F. Read in command.

The third ship of the USN to be named Revenge, the schooner began her service in the era of President Thomas Jefferson’s Gunboat Navy, a time defined by a naval doctrine predicated on Jefferson’s belief in and preference for a naval force of small gun boats designed to protect America’s home waters. A gunboat being a relatively small ship approximately 50 feet long and 18 feet wide with a shallow draft; designed for close combat in coastal waters. The new strategy greatly inhibited the ability of the USN to operate effectively in the open ocean.

Jefferson’s naval policy occurred at a precarious time for the young Republic, as war raged in Europe between Napoleonic France and the Third Coalition, one of whose belligerents included the British Empire. In the face of the conflict Jefferson’s America endeavored to remain neutral, much to the ire of both France and Britain. A fact which was further aggravated by the British supremacy of the seas secured at the decisive Battle of Trafalgar, on 21 October 1805, in which, combined French and Spanish fleets were defeated by a British fleet led by Vice Adm. Horatio Lord Nelson. The Royal Navy’s nearly undisputed command of the seas gave rise to a policy of confiscating American ships and impressing American sailors.

The threat of British sea power coupled with the presumed malign intentions of Spain in Louisiana Territory, made Revenge’s initial assignment in New Orleans an integral part of the need for enhanced sea power in the area. Thus, Revenge’s assignment in New Orleans was directly related to the Aaron Burr Jr. (1756–1836) conspiracy of 1806. Although the complete details of Burr’s plans remain debated by historians it was believed that in addition to spying for Spain and possibly Britain that he along with his alleged partner Gen. James Wilkinson (1757–1825) had plans to claim portions of Texas and the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, purchased in 1803; and of which Wilkson was the governor. Burr was indicted for treason by Jefferson, but ultimately acquitted, and Wilkinson, by the merit of his own word was cleared of involvement.

Revenge remained stationed at New Orleans in the midst of this climate of intrigue and mounting military tension until June 1807 when she weighed anchor and set sail for Baltimore. On 22 June 1807, the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair took place just off the coast of Norfolk Va., in which the British fourth rate HMS Leopard engaged the American frigate Leopard under the pretense of looking for RN deserters. Three of Chesapeake’s crew members were killed, 18 wounded, and four others were seized for being British deserters. The incident incited a national uproar, Jefferson saying of it that not “since the Battle of Lexington have I seen this country in such a state of exasperation as at the present.” As part of the initial response U.S. Secretary of State James Madison had diplomatic papers prepared to demand that Britain both disavow the transgression and pay reparations.

The delivery of the diplomatic papers related to the affair was entrusted to USN Surgeon John Bullus. Revenge was called upon to transport Bullus to England and thereafter to France. After getting the orders Revenge was fitted out for her voyage across the Atlantic. On 11 July 1807, Lt. Cmdt. Read notified Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith that Revenge was ready for sea and soon thereafter weighed anchor. In a letter sent from Falmouth, England, on 5 September 1807, Read reported that Revenge had arrived in England on 27 August. A few days later on the 31st, Bullus delivered his diplomatic papers and parlayed for the return of the impressed American sailors; despite his efforts the British gave no acquiescence to his entreaty. On 10 October, he returned on board Revenge and the ship set out for Cherbourg, France, to retrieve dispatches from Paris related to ongoing events on the continent.

Shortly after picking up her dispatches in Cherbourg, Revenge shaped a course for New York. While she was still en route across the Atlantic Jefferson communicated to the U.S. Congress his plan for an embargo of all trade with nations implicated in interfering with American commerce and although it is not known if Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807, would have been passed prior to the return of Revenge it was not voted on until afterwards. The schooner at last passed through the narrows of New York harbor on 12 December 1807. Bullus disembarked and traveled posthaste to the Federal City (D.C.), where, on the 16th, he reported to the Congress.

Of primary note in Bullus’ address was the information he obtained from France which gave full notice to the American people of Napoleon Bonaparte’s conviction that there should be “no neutrals,” regarding his Berlin Decree of 21 November 1806, which forbade all nations from commerce and correspondence with Britain. The decree formed the foundations of Napoleon’s Continental System, which sought to block Britain from all trade with Europe. Unfortunately for Napoleon the policy ultimately harmed him more than Britain due largely to the RN’s command of the world’s oceans.

Jefferson’s Embargo Act was signed into law on 22 December 1807, and tied as she was to these momentous events Revenge again played her part. In the aftermath of the Act she was assigned to Commodore John Rodgers’ New York Flotilla which had been charged with blockading the U.S. coast to prevent foreign commerce. While successful in averting war with Britain, the Act did little long term damage to Britain and put heavy strain on the U.S. economy which in turn caused the measure to become quite unpopular. Revenge nonetheless, dutifully performed her role in the blockade.

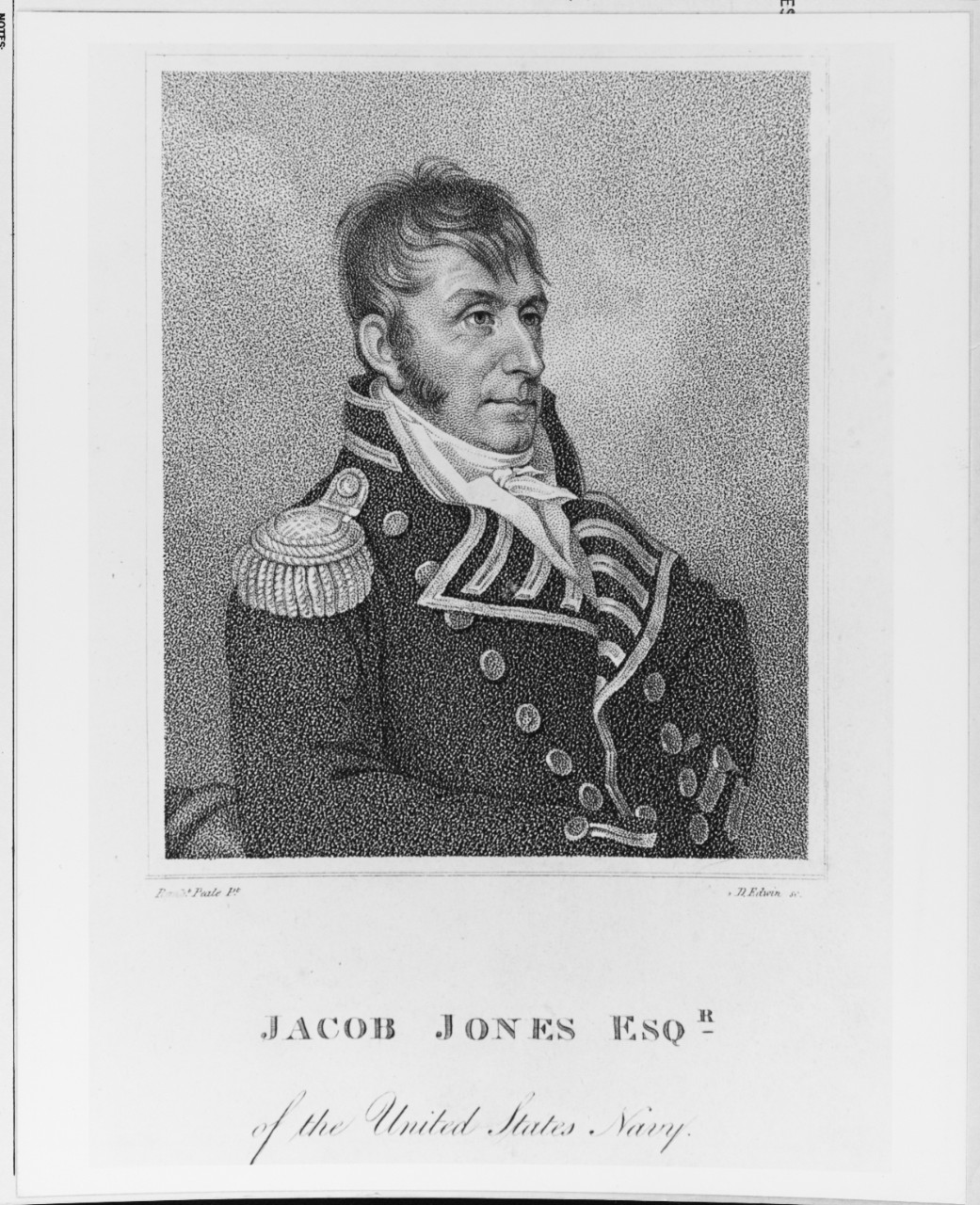

Correspondence indicates that Lt. Cmdt. Jones replaced Read as the commander of Revenge between February and March 1808. With Jones in command, Revenge continued her blockading duties with the New York flotilla into the next year. Due to mounting opposition, the Embargo Act was repealed by the Congress in March 1809, shortly after Jefferson left office, and Revenge was released from the blockade, but remained attached to Rodgers’ squadron. The newly elected president James Madison ended Jefferson’s gunboat policy which had proved to be ineffective for both the naval defense of the U.S., as well as for the defense of its merchant fleets on the high seas.

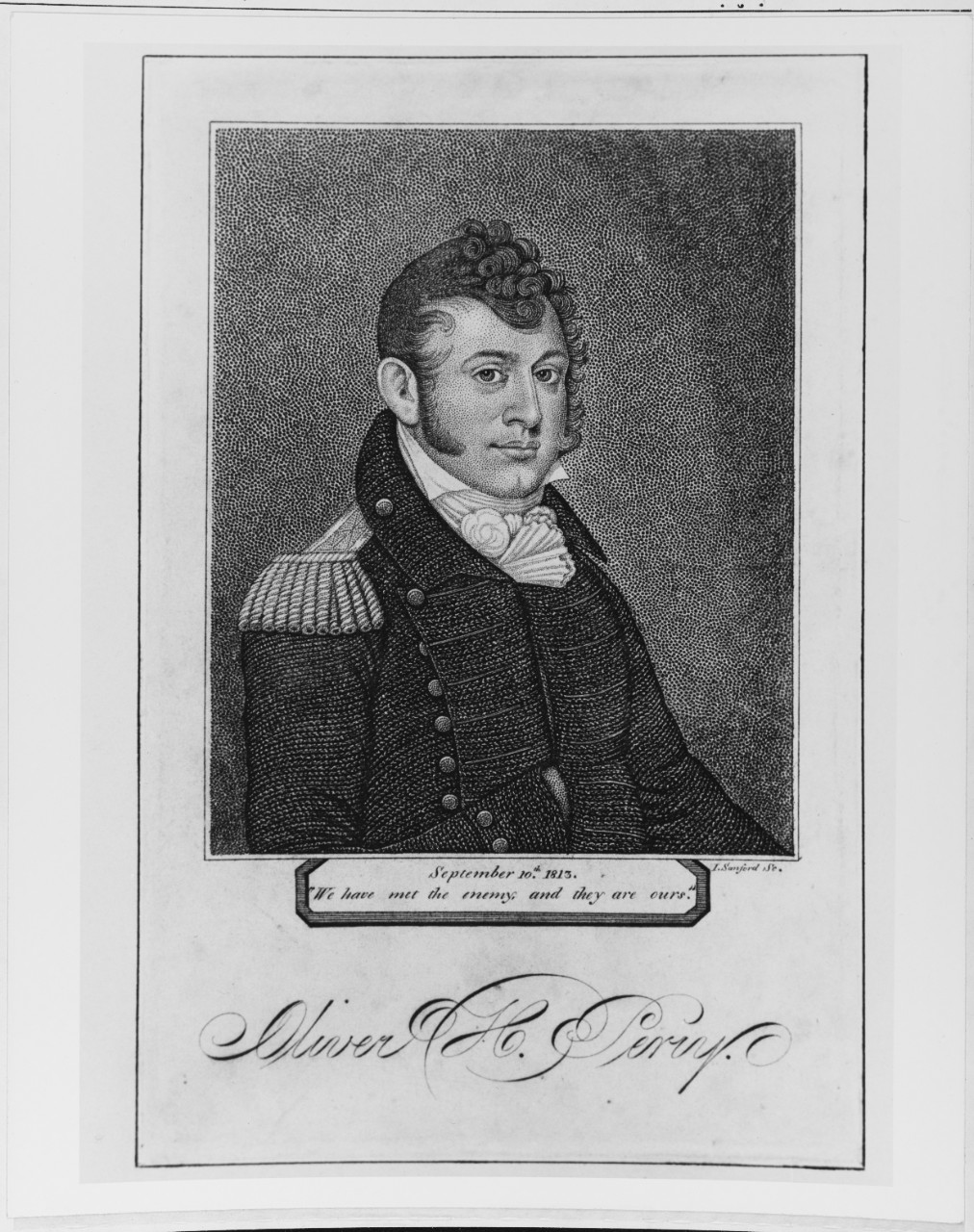

By late May 1809, Revenge lay anchored in New York and her command passed to Lt. Cmdt. Oliver Hazard Perry. As the year progressed Revenge, still serving as part of Rodgers’ squadron, engaged in routine patrols along the eastern seaboard venturing from New England to the southern tip of Spanish Florida. In April 1810, the schooner was ordered to the Washington Navy Yard, D.C., for some extensive repair work. While en route, and in accordance with the unofficial tradition then in place, she fired a customary salute as she passed Mount Vernon, the estate of former President and General of the Army George Washington.

With her repairs complete and provisions stowed Revenge weighed anchor and set sail from Washington on 20 May 1810 charting a course for Charleston, S.C. She encountered a bad storm during the voyage, which resulted in significant damage and the loss of several spars. The cruise also witnessed the near death of one of the warship’s embarked marines; Johnson Dickson, who fell overboard, but was fortunately recovered, none the worse for wear.

Following the completion of some additional repairs in Charleston, Revenge again put out to sea on 22 June 1810, to protect the nearby coast from encroachments by ships of the RN. In mid-July, while cruising nearby Cumberland Island, off the coast of Georgia, Perry received a U.S. marshal on board who delivered a U.S. District Court warrant for the seizure of a captured American vessel, located at Amelia Island, Fla., which was then still under the control of Spain.

The ship in question, Diana, was being sailed under British colors and by the false name Angel, owing to her seizure in Spanish waters the month prior. Despite the fact that permission had been given to the U.S. government by the Spanish governor of Amelia to reclaim the vessel she nonetheless stood under the battery of the British 12-gun gun-brig HMS Plumper and the 50-gun fourth rate HMS Jupiter. Undaunted, Perry manned her with a prize crew and sailed out of Spanish waters unmolested.

Revenge anchored with the restored Diana off Cumberland not long after their departure from Amelia. Under the orders of her rightful owner Diana eventually made port in Savannah, Ga., but prior to her departure from Revenge’s company the pair encountered a British warship in an event that for a moment very nearly could have been a repeat of the infamous Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. Having spotted a large sail on the horizon while she was still off the coast of Cumberland, Revenge shortly thereafter found herself in the presence of HMS Goree, Capt. Henry Dilkes Byng in command. A British officer was sent to Revenge to request that the schooner’s commanding officer accompany him on board Goree to explain the vessel’s charter.

Notwithstanding his disadvantage in armament Perry refused the demand and, in the event that it would have been necessary, prepared his men for a boarding action against Goree. Fortunately for all parties involved Byng agreed to a settlement in which, Perry sent one of his junior officers to explain the charter. The two ships parted company in peace and for a short time afterwards Revenge continued to patrol the coast of Georgia before eventually returning to Charleston.

Revenge weighed anchor and set sail from Charleston on 10 August 1810, to return to New York, to resume her duties as part of Rodgers’ squadron in New England. The fleet there engaged in a vigorous patrol of New England waters and upon her arrival, Revenge took up her station cruising between Montauk Point and the south shoal of Nantucket; with Newport as her point of rendezvous. During the cruise Perry endeavored to keep the crew in top shape engaging them continually in gunnery exercises.

In December 1810, Revenge sailed to her winter quarters in New London, Conn., however not long after her arrival, Rodgers’ ordered Revenge to survey the harbors of New London, Newport, R.I, and Gardiner’s Bay, Long Island, N.Y. It was an unfavorable season to be conducting surveys and in difficult waters at that, but with mounting tensions between the U.S. and Britain, Rodgers was eager to have the surveys completed as soon as possible. Perry in particular was selected due to both his excellent record of seamanship as well his scientific aptitudes.

Newport was given the first priority and Perry quickly set about his work. Although originally he was only given a week to complete the survey he encountered bad weather and was forced to request an extension to complete the task. While in Newport Revenge was again allayed for several more days by a contrary wind and heavy fog that prevented her from sailing. At last however, at midnight, on 9 January 1811, the schooner was able to return to her work and she departed Newport with a light northeast wind. The late hour was chosen so that the vessel could navigate the dangerous strait between Fisher’s Island and Watch Hill by daylight. Mr. Peter Daggett was that day serving as the acting sailing master and pilot. Despite the hazardous weather and season Daggett assured Perry the voyage would be uneventful.

A heavy fog set in as Revenge passed through the western extent of Block Island Sound and while Perry was below decks, the ship ran aground on a reef in the vicinity of Watch Hill Point. As the disaster struck at the precipice of high water the probability of rescuing her was minimal, nonetheless, Perry tried desperately to do so. Boats were put out, numerous heavy items, along with eight guns were thrown overboard while water pumps and sailors worked tirelessly to bale water with buckets. Minute guns were fired as a sign of distress and Perry ordered that the main and foremast be cut down. Despite these efforts all hopes of rescuing the vessel quickly diminished and Perry hastily set about instructing the safe removal of the crew.

Sick men, marines and boys were sent ashore in the first boats and thereafter the crew set about removing what items of value could be salvaged. Throughout the course of the day the sails, rigging, small arms and some cannon were removed. However, by sunset the wind began to blow fiercely and the surf was nearly breaking over the remaining wreckage of the vessel—these miserable circumstances were further compounded by a bitter cold wind. By nightfall all hands were safely mustered ashore, with Perry being the last to leave the wrecked schooner.

The morning following the tragic ruin of Revenge a portion of the wreck consisting of the deck and bulwarks was seen floating off the reef. The American frigates Constitution and President had arrived from New London during the night to aid Perry and his crew. A smack (small traditional fishing boat), which also arrived later that day assisted in towing the wreck to Fisher’s Island. During that process the remainder of the schooner’s armaments consisting of six light carronades were also recovered. Despite salvaging efforts, the weather remained exceedingly harsh and the wreck was eventually abandoned.

As the loss of a ship is certainly no small matter, a standard court of inquiry took place shortly after the incident. The presiding officers determined that Perry had exerted considerable efforts to keep the vessel afloat, ensure the safety of the crew and salvage what implements of the ship could be reasonably saved. The fault for the ship’s unfortunate grounding was laid entirely at the door of the pilot Mr. Daggett. Satisfied with the findings of the inquiry Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton wrote to Como. Rodgers that “Having attentively examined the proceedings of the court, I derive much satisfaction from perceiving that it is unnecessary to institute any further proceedings in the case… The loss of the Revenge seems to be justly chargeable to the pilot. This accident will no doubt present to Lieutenant Perry consideration that may be useful to him in future command.”

In August 2005, Connecticut divers Charles Buffum, Craig Harger, and Mike Fournier discovered Revenge’s wreckage, finding four cannons, two carronades, an anchor and numerous other concreted artifacts at the site. On 23 May 2017, the Naval History and Heritage Command’s Underwater Archaeology team mapped the location and retrieved a single cannon for diagnostic purposes, as well as performed archeological research. Excavation and documentation of the site remains, at the time of this publication, ongoing.

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Lt. Cmdt. Benjamin F. Read | December 1806–January 1808 |

| Lt. Cmdt. Jacob Jones | February or March 1808–April 1808 |

| Lt. Cmdt. Oliver Hazard Perry | May 1809–January 1811 |

Jeremiah D. Foster

31 October 2018