Pueblo III (AGER-2)

1967–1968

The third U.S. Navy ship named for a city in Colorado and the first for a county in that state. Colorado (Armored Cruiser No. 7) 1905–1930 was renamed Pueblo on 9 November 1916, and frigate Pueblo (PF-13) served from 1944–1946.

III

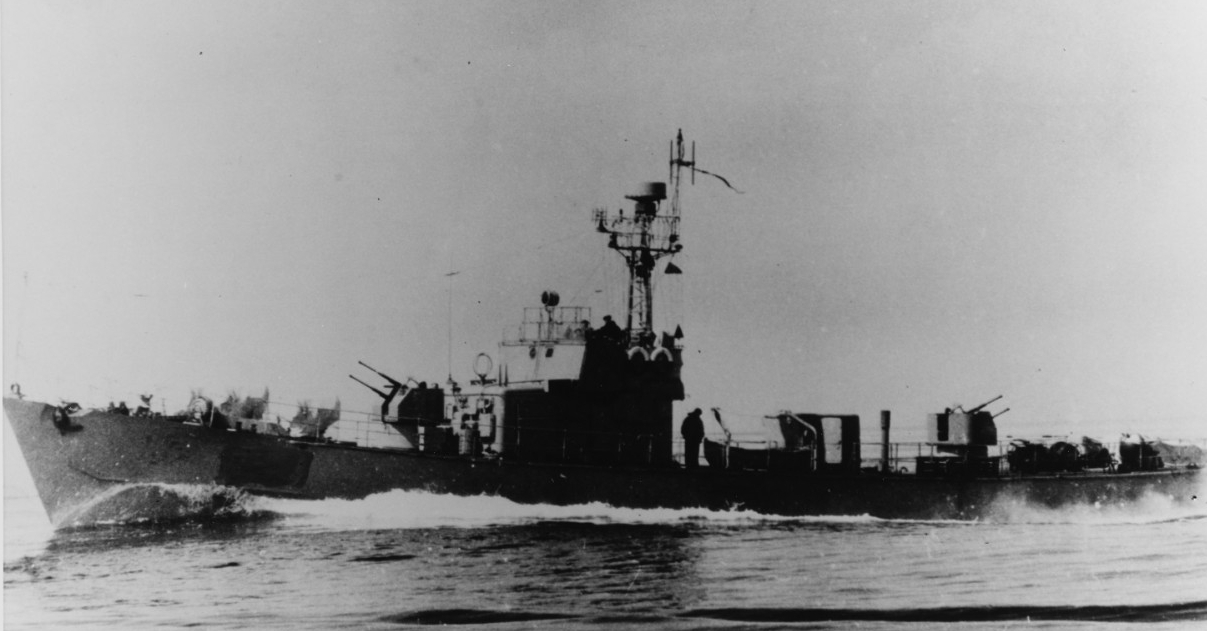

(AGER-2: displacement 895; length 176'6"; beam 32'; draft 9'3"; complement 83; speed 12 knots; class Banner)

The third Pueblo (AGER-2) was built as Hull 66 by the Kewaunee Shipbuilding & Engineering Corp., Kewaunee, Wisc.; renamed Army Transportation Corps freight and passenger vessel FP-344; launched on 16 April 1944; and sponsored by Mrs. Dorothy K. Duvall, wife of Mayor Clarence L. Duvall of Kewaunee and mother of 22-year-old 2nd Lt. Clarence G. Duvall, USAAF, who was killed when the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress he was flying crashed in a snowstorm near Maxwell, Iowa, at about 0600 on 6 March 1944.

FP-344 was delivered to the Army on 5 July 1944; and commissioned on 7 April 1945, at New Orleans, La., Lt. Joseph H. Choate III, USCGR, in command. Lt. (j.g.) Marvin B. Barker, USCG, relieved Choate on 12 September 1945. A Coast Guard crew manned the ship and used her to train civilians who supported the Army. Later reclassified to freight and supply vessel FS-344, she served in the Philippines as an Army harbor craft until 1954, when the ship was taken out of service and laid up, first at Clatskanie, Ore., and then at Rio Vista, Calif.

Increased Soviet spy trawler deployments during the Cold War led the U.S. Navy to develop a modest program of specialized vessels to supplement aircraft, ships, and submarines that collected intelligence. The National Security Agency (NSA) envisioned that some of these vessels would operate as environmental research ships (AGERs) and be manned by Navy crews, augmented at times by civilian specialists that coordinated their missions with the NSA. The ships would be specifically configured to collect signals intelligence, comprised of electronic intelligence and communications intelligence, as well as collateral intelligence and hydrographic information.

A special House of Representatives subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services (Ninety-First Congress, First Session) was established on 18 February 1969 to investigate the attack on Pueblo (see below). The subcommittee evaluated the program and noted that planners envisioned developing it in three phases. During Phase I, a single ship would deploy under the operational control of the Seventh Fleet, except while carrying out surveillance operations along the western reaches of the North Pacific Rim. The vessel would primarily test how a single AGER could carry out surveillance and intelligence collecting activities. Phase II expanded Phase I’s objectives in order to determine the future of the program and included “maximum collection of all types of intelligence in support of national and naval intelligence collection requirements.” Phase III depended upon the success of the first two phases but the people involved in the project hoped to “expand the effort” and that additional ships could be added to the program to provide continuous coverage of areas in which collection deficiencies exist.”

The NSA’s budget staff considered deploying up to 25 such ships in total, and after much deliberation by the agency and the Navy, requested 12–15 AGERs for Phase III in its Combined Cryptologic Program submission for fiscal years 1966–72. The Department of Defense budget reduced this number so that only three light cargo ships were initially earmarked for conversion to a similar design — Banner (AKL-25), Palm Beach (AKL-45), and Pueblo (AKL-44). Banner served with the Pacific Fleet and was converted first at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Wash. (July–September 1965). Banner was reclassified to an environmental research ship (AGER-1) on 2 May 1967, and through the end of the year completed 16 Clickbeetle (intelligence gathering) patrols while operating out of Yokosuka, Japan. The Soviets and Chinese harassed her at times but the incidents did not escalate.

Banner’s experience, meanwhile, influenced Secretary of the Navy Paul H. Nitze and on 7 October 1965, the secretary expressed his concern to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara about acquiring actionable intelligence on the latest naval deployments of the Soviets and their East Bloc proxies, as well as their operations, tactical doctrine, procedures, and training. In order to accomplish that objective, Secretary Nitze recommended that the U.S. should immediately add at least the two additional environmental research ships. On 2 December 1965, Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus R. Vance endorsed a recommendation by the office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Systems for the Navy to acquire FS-344.

No longer needed by the Army, FS-344 was accordingly transferred to the Navy on 12 April 1966. Less than a week later, on 18 April 1966, she was named Pueblo and classified as a light cargo ship (AKL-44). She reached Puget Sound on 22 April, where, on 5 July 1966, she began conversion while assigned to Service Force, Pacific Fleet. Workers sandblasted the hull, removed cargo winches, tested engines and machinery, and examined cables. Following most of the work on the hull, Ling-Temco-Vought of Greenville, Texas, the contractor that had provided the signals intelligence collection equipment for Banner, installed similar gear on board Pueblo. Reclassified to AGER-2 on 2 May 1967; Pueblo was commissioned in company with Palm Beach (AGER-3) on 13 May 1967, Cmdr. Lloyd M. Bucher in command.

Some aspects of Pueblo’s conversion differed from those the Navy normally encountered in ship conversions. Pueblo belonged to a unique class and many details, such as allowance lists of equipment and spare parts, and supply lists of stores for the special equipment, did not exist and the commissioning crew generated them with the assistance of the appropriate technical offices. Security considerations limited the information about the ship that circulated throughout the fleet and as a matter of routine she continually received supplies for a small cargo ship, many of which did not match her requirements. The planners originally intended for the vessel to serve unarmed, but for physical security of the crewmen her allowance included ten M1 Thompson submachine guns, seven M1911A1 .45 caliber pistols, one M14 rifle, and hand grenades.

On 28 August 1967, Adm. Thomas H. Moorer, Chief of Naval Operations, advised Vice Adm. Ignatius J. Galantin, Chief of Naval Material, of a decision to install defensive armament of at least 20 millimeter guns on board all commissioned naval vessels not so equipped. Rear Adm. Frank L. Johnson, Commander, Naval Forces Japan, later testified before the subcommittee that he did not receive the directive, and at any rate, Pueblo’s size, construction, and weight distribution convinced planners not to install heavier armament. Pueblo was never intended to fight a pitched battle at sea, but the service authorized machine guns as an “interim armament” so that the ship might be able to defend herself against small boats. “Piracy on the high seas was considered to be unlikely,” Moorer stated before the subcommittee on 4 March 1969, “Pueblo was not nor could she be considered a combatant ship.”

In the interim, the Navy expanded the integrated naval surveillance and intelligence ship program into Phase II, which included converting and deploying two of the Banner class ships to the North Pacific Rim so that after allowing for maintenance and upkeep at least one of the ships could observe East Bloc naval and air operations at any given time. Lt. Edward A. Brookes, the fleet support officer for the Intelligence Division at Naval Forces Japan, served as the project officer and prepared the initial plans in March 1967. Upon ascertaining that Pueblo was to be available early in the New Year, Brookes and planners at that command originated a six-month plan of operations that would deploy the vessel at times into the following summer (January–June 1968). The environmental research ship thus wrapped-up her yard work and sailed from Puget Sound and, after stopping briefly at San Francisco, Calif., reached San Diego, Calif. (11–22 September 1967).

Pueblo berthed at the Fleet Antisubmarine Warfare Command’s docks at Point Loma and at times before she deployed, officers attended officer of the deck training and the communications school, and most of her Naval Security Group Detachment, which was activated on 29 September 1967, attended firefighting and damage control training. Pueblo also carried out her shakedown cruise in southern Californian waters (25 September–20 October). The evaluators ran her departments and teams through a variety of exercises including working out the watch sections, ship control, seamanship, operations, communications, and engineering. Pueblo completed all of the problems satisfactorily and received an overall grade of “Good”, the mid-mark between Outstanding and Satisfactory. She accomplished some routine post-conversion repairs and reported ready for duty to the Pacific Fleet in November.

Pueblo sailed on her maiden voyage from San Diego on 6 November 1967, en route to her home port of Yokosuka. The ship turned her prow to sea with the additional manning that raised the complement to 83, including Lt. Stephen R. Harris, USNR, the officer in charge of her Naval Security Group Detachment, and 29 enlisted men of the detachment. The cryptologic technicians (CTs) spent most of the voyage to Hawaiian waters copying weather broadcasts and familiarizing themselves with their specialized equipment, but the ship’s steering mechanism malfunctioned repeatedly.

Pueblo refueled and provisioned at Pearl Harbor, Hi. (14–18 November 1967), and workers repaired her steering apparatus. Cmdr. Bucher consulted Lt. Cmdr. Ervin R. Easton of the Pacific Fleet’s staff, who informed Bucher that the ship was to deploy to the Sea of Japan. Pueblo then made for Japanese waters but the temperature dropped and the weather turned foul. Conning the ship from the flying bridge chilled the men on watch, and heavy seas pitched the vessel about and taxed the crew below, who found it all but impossible to operate equipment with any degree of efficiency during such weather. The men tied down chairs using nylon straps through rings in the deck plates and secured other equipment but strong rolls still threw them from their seats, worked equipment loose in the racks, and spilled paper stored in the overhead.

At one point an RM1 of the ship’s company suffered injuries and required evacuation for medical care. The ship sent a radio message requesting his transfer and destroyer tender Samuel Gompers (AD-37), which also steered toward Yokosuka on a roughly parallel heading but some distance behind, charted a course toward Pueblo. After nearly 20 hours of steaming on an intercept course Samuel Gompers’ lookouts sighted Pueblo ahead, in a position about 1,886 miles from Yokosuka, near 28°25ˈN, 166°55ˈE, at 0752 on 25 November.

The tender approached to port of the environmental research vessel and lowered her starboard motor whaleboat, which pulled alongside Pueblo so that Lt. John Anderson, MC, Samuel Gompers’ medical officer, could board and examine the injured man. Crewmen placed the patient into Pueblo’s motor whaleboat and lowered it into the water, and the boat then crossed to the tender and sailors hooked it to the boat falls and raised it to the main deck, where they transferred the man to sick bay for treatment. After they loaded provisions into Pueblo’s boat, they lowered it away and it returned to the ship, while the first boat also crossed back over and returned to Samuel Gompers. The tender reached Yokosuka on the last day of the month, and transferred the patient ashore to the naval hospital.

Pueblo reached Yokosuka on 1 December 1967, but the steering system failed and a tug shepherded the ship into the harbor, where, five days later she was administratively assigned to Service Group 3. The ship accomplished voyage repairs and upkeep over Christmas while at Yokosuka, which included rebuilding the steering mechanism, and installing a tinted, plexiglass windscreen on the flying bridge to protect watchstanders from the wind and salt spray. In addition, workers installed three machine gun mounts, two located forward on the forecastle deck, one port and the other starboard, and the third located aft on the centerline of the boat deck. Pueblo received the two .50 caliber machine guns authorized but not a third, and the weapons were installed without shields. The ship carried 10,000 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition, about 9,600 in ready-service boxes near the guns and the balance stored below decks in the paint locker. Approximately 25 crewmen practiced firing the guns during an orientation detail at the nearby USMC target range, and some men subsequently practiced at times when the ship sailed on her patrol. Among the projects carried out, workers overhauled the ship’s steering apparatus, and checked and calibrated all of the navigation gear, including her Loran-C radio navigation system, bearing circles, alidades, radar, and fathometer.

Pueblo reached the region at a tense time. During the mid-1960s the North Koreans behaved aggressively toward U.S. ships and aircraft that operated off their coasts and accused them of spying, as well as against South Korean patrol craft and fishing boats, and dramatically increased their raids across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North Korea and South Korea. Some of these incidents escalated dangerously and on 28 April 1965, a pair of their Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 Frescos attacked and damaged a USAF Boeing RB-47H Stratojet flying in international air space more than 35 nautical miles from their coast. They then somewhat reduced the instances of vectoring their jets to intercept American patrol aircraft, but dramatically increased attacking and harassing South Korean vessels (1966–1968), and their Korean People’s Army Air Force assumed an increasingly active role in these maritime clashes.

U.S. intelligence analysts assessed the risk that these attacks posed to vessels such as the Banner class ships as they carried out their patrols, and provided their analyses to naval commanders. While Pueblo lay at Yokosuka on 16 December 1967, Rear Adm. Johnson utilized such intelligence when he proposed the ship’s first mission in a message to Vice Adm. John J. Hyland Jr., Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, with information copies to multiple recipients including Vice Adm. William F. Bringle, Commander, Seventh Fleet, Lt. Gen. Seth J. McKee, USAF, who led the Fifth Air Force, and Pueblo. “Estimate of Risk: Minimal,” the message summarized, “since PUEBLO will be operating in International waters for entire deployment.”

The NSA sent a message to addressees including the Joint Reconnaissance Center on the 29th that also stated that “Risk to Pueblo is estimated to be minimal since operations will be conducted in international waters.” The agency briefly alluded to previous incidents and highlighted the North Koreans’ sensitivity to American aircraft and ships making surveillance patrols off their coasts, and significantly said that they did not generally honor “internationally recognized boundaries as they relate to airborne activities” off their east coast, but that there was no “evidence of provocative harassing activities” by their vessels beyond 12 nautical miles from their shore. The NSA provided the information to “aid in evaluating ship protective measures,” however, the message failed to emphasize how aggressively the North Koreans’ might react to what they could potentially consider a provocative move toward their coastal waters.

Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analysts from the agency’s Special Reconnaissance Branch in the Directorate for Intelligence Production and from the Directorate for Collection also assessed the mission’s risk as low. They reviewed some of the incidents during the previous two years in which North Korean jets had intercepted U.S. aircraft flying in international airspace, but because the North Koreans had not hitherto intercepted U.S. naval vessels, the agency assessed that their naval craft would only intercept South Korean ships. The DIA’s risk assessment also noted that the Soviets and Chinese had not reacted excessively toward similar voyages, and that the North Koreans would likely follow their lead.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Pueblo’s mission without changes early in the New Year on 2 January 1968. On the 4th Capt. Thomas L. Dwyer, the assistant chief of staff for intelligence at Naval Forces Japan, Cmdr. Bucher, Lt. Brookes, Lt. Cmdr. Charles R. Clark, Banner’s commanding officer, and other staffers attended an intelligence briefing at the Naval Forces Japan headquarters. The attendees discussed several issues including North Korean claims to a 12 mile territorial sea, and recommended that Pueblo should stay outside that limit and not steam closer to that country’s coast than a 13 nautical mile safety zone. On the 5th, Rear Adm. Johnson issued OpOrder 301-68, the ship’s operations order, which fittingly fell within a plan designated Ichthyic I (fishlike). Pueblo’s order again emphasized that she was to operate in international waters and not to approach the Korean coast or offshore islands closer than 13 nautical miles, and to operate to seaward to 60 nautical miles.

The ship was to deploy to three operation areas (from north–south), Pluto (42°–41°N), Venus (41°–40°), and Mars (40°–39°), “concentrating efforts in most lucrative areas.” Pueblo was to come about on 27 January 1968 and patrol in the vicinity of the Tsushima Strait, the eastern channel of the Korea Strait, and return to Sasebo on 4 February. The vessel was to operate whenever possible in ‘emission control’, which meant that at times crewmen would shut down electronic systems such as radar to minimize their signals, to prevent the Soviets from readily intercepting the signals and thus identifying the ship’s movements. Whenever Pueblo operated in proximity of Soviet vessels, she was only to close briefly to 200 yards so that analysts could photograph their Cold War opponents, and then open the range to at least 500 yards. Furthermore, the .50 caliber machine guns were to be “stowed or covered in such a manner as to not elicit unusual interest” from communist forces, and her crewmen were to employ the weapons “only in cases where threat to survival is obvious.”

Pueblo stood out of Yokosuka on 5 January 1968 and for three days rounded the Japanese home islands to Sasebo, Kyūshū. The Fleet Weather Facility at Yokosuka forecasted “fair weather conditions” through March but at one point during the voyage the ship plowed through heavy seas. Pueblo was originally scheduled to deploy on 8 January, but the foul weather delayed the vessel while her crew and civilian workers made final repairs to the electronic equipment. Pueblo set out during the morning watch on the 11th, and to avoid detection by a Soviet destroyer and tanker plying the Tsushima Strait chartered northerly courses close to the shores of Kyūshū and Honshū. A winter storm lashed Pueblo as she passed through the Tsushima Strait and made for her initial operating areas in the Sea of Japan. The ship rolled mercilessly and many of the crewmen struggled with seasickness, and the heavy swells compelled her to alter course some 70 miles out to sea to continue the voyage. As the ship escaped the storm and worked her way northward, the weather nonetheless continued to be overcast with six mile visibility and westerly winds at 14–20 knots. The temperature turned penetratingly cold and a thick sheen of ice formed on the deck overnight, so Bucher ordered all hands to chip away at the ice to avoid making the ship top heavy.

On 8 January 1968 meanwhile, the Foreign Broadcast Information Service reported that Radio Pyŏngyang accused the Americans of committing provocative acts along the east coast of Korea and threatened retaliation. The service reported another such broadcast three days later. Journalists later seized on these reports to allege that the North Koreans thus tipped their hand that they intended to seize the ship, and that U.S. commanders in the region disregarded the warnings. Officers at the Pacific Fleet and at Naval Forces Japan afterward claimed that they did not see the reports, however, and when shown the broadcasts noted their similarity to previous North Korean threats.

Pueblo in the meantime continued her voyage and entered operational area Pluto, the northernmost of her operating areas, and spent two days off Chongjin in a position about 15–16 miles east and slightly southeast of that North Korean port. Bucher ensured that the ship operated outside North Korean territorial waters, and ordered watchstanders to cut navigational fixes to verify their position every half-hour during the day and every 20 minutes at night. Pluto proved aptly named and men laboriously chipped away at the ice that continued to accumulate, and the heating system in the crew’s quarters failed to function properly and added to their discomfort. “We had trouble with the water all the time…” CT3 Ralph McClintock recalled about an additional flooding problem, “the bilge pump was backing up or something and I’d wake up in the morning sometimes and find everything floating around the deck.” In spite of the hardships the crew otherwise considered the initial part of the patrol routine, and lookouts sighted several North Korean fishing boats and commercial vessels, but they did not demonstrate interest in Pueblo.

She then steamed overnight to operating area Venus off the Sŏngjin [Kimchaek] area, arriving on the morning of 18 January 1968. The ship noted very little activity in that area and her icing difficulties decreased. Pueblo moved on to Mars, the southernmost of her operating areas, in the vicinity of the island of Mayang Do on 20 January, an overcast day with good visibility and light southwesterly winds. At twilight at 1730 a North Korean SO-1 class submarine chaser passed at a range of 500–1,000 yards but continued on her way. Pueblo shaped a course for the waters off the port of Wŏnsan overnight on 21 January and reached that area by morning.

Thirty-one North Korean commandoes of the 124th Guerilla Detachment attempted to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee at the Blue House, that country’s executive office and residence in Seoul, on the night of 21 January 1968. The South Koreans defeated the assassins, but friction ran high and diplomats scrambled to prevent the crisis from escalating. American forces were heavily embroiled in the Vietnam War and deployed globally to contain the East Bloc during the Cold War, and the crisis exacerbated U.S. defense planners’ concerns about multiple commitments. News of the attack failed to reach Pueblo and the ship continued her patrol unaware of the burgeoning crisis.

A slight breeze touched the air as 22 January 1968 dawned, bright but brisk. Just after noon at 1225, lookouts on board Pueblo spotted a pair of North Korean ships bearing 170º at 10,000 yards, and moving at a speed of eight knots, about 17 nautical miles off the North Korean coast. The prowlers suspiciously changed course and approached the ship, which stopped engines. The grey, heavily laden North Korean ships resembled Soviet Lentra class trawlers and did not break flags, but each displayed stern black-red-black stack markings with a red star in a white circle in the center of a red band, and the Americans translated their names as Rice Paddy (P/N 1-065), and Rice Paddy One (P/N 1-062). The trawlers stowed apparent fishing nets forward but lacked discernable radar, electronic antennae, or guns and apparently operated as submarine chasers. The North Korean ships proceeded close aboard to starboard, closed and steamed menacingly aft down Pueblo’s port side, cut across the American vessel’s stern, and passed up her starboard side. The submarine chasers queried Pueblo, to which she replied that she operated in international waters, and the North Koreans came about. Pueblo moved out to sea overnight and reported 18 contacts, and at one point her lookouts sighted an orange flare, and by morning reached a point slightly to the northwest of her previous position.

The following day, 23 January 1968, opened briskly but calm without heavy swells. The morning passed uneventfully until about 0930, when CT1 David L. Ritter intercepted two North Korean submarine chaser radar signals on the AN/WLR-1 countermeasures receiving set that he operated and reported them to the bridge. Pueblo continued her routine and QM1 Charles B. Law Jr., relieved CWO3 Gene H. Lacy as the officer of the deck at 1145 and assumed the afternoon watch. Five minutes later the ship lay dead in the water with her auxiliary diesel running, in a serene sea, and the temperature rose only to a biting 36ºF, when Law sighted North Korean submarine chaser P/N 35 in the distance. Law summoned Bucher to the bridge and the commanding officer ordered all hands to remain below decks in order not to indicate the size of the crew. The North Korean ship rapidly closed Pueblo and signaled “What nationality,” to which Bucher ordered the national ensign and “Hydrographer” hoisted. The intruder circled Pueblo twice and the ship transmitted “company outside,” lit-off her engines to prepare to maneuver, and steamed at one-third speed to the northeast.

At about 1220 North Korean P-4 class torpedo boats P/N 601, P/N 604, and P/N 606 joined P/N 35 “Heave to or I will open fire on you,” P/N 35 hoisted seven minutes later. Bucher verified the ship’s position as 15.8 nautical miles from the nearest land and responded “I am in international waters.” By 1300 the North Korean vessels took up threatening positions around Pueblo — P/N 35 and P/N 604 off Pueblo’s starboard bow, P/N 606 just forward of her starboard beam, and P/N 601 off the starboard quarter. Bucher passed the word through the 1MC main circuit public address system for all hands to prepare to destroy classified material. Two MiG-21 Fishbeds roared in and circled the scene.

“Follow in my wake, I have pilot on board,” P/N 35 signaled, but an armed boarding party transferred from the submarine chaser to P/N 604, which rigged fenders and began backing down on Pueblo’s starboard bow. “Thank you for your consideration, I am departing the area,” Bucher responded, and ordered one third speed and right rudder. He considered manning the machine guns but rejected the tactic because he “…saw no point in senselessly sending people to their death.” Pueblo swung round to course 080° but the North Korean vessels repeatedly crossed her bow, and P/N 35 signaled again, “Heave to or I will fire.” The beleaguered U.S. ship kept way on for about five minutes, increased her speed to standard, and then rang up full speed of just over 12 knots, but could not outrun the faster North Korean craft. P/N 601 uncovered a torpedo tube and trained it on Pueblo.

Suddenly at 1327, P/N 35 opened fire with her 57 millimeter gun from a range estimated at 1,500 to 2,000 yards. The North Koreans’ apparently fired warning shots but fragments hit the radar mast and wounded Bucher in the ankle and rectum, another man in the neck, and a third in the leg. P/N 35 shot an estimated 15 bursts of 6–14 57 millimeter rounds in about seven minutes, and North Korean machine guns also raked Pueblo in light bursts and fired nearly 2,000 rounds. The men on the flying bridge sought what limited cover they could find topside by shifting to the pilot house, but the rounds destroyed glass and plexiglass in the pilot house and glass shards wounded Ens. Timothy L. Harris, the ship’s supply officer.

“Commence emergency destruction,” Bucher ordered through the 1MC. Shortly thereafter, he sounded general quarters. While he modified the order to prevent men from exposing themselves topside to the North Koreans’ fire, the order kept anyone from manning a sound-powered telephone on the bridge, which hindered communications. Manning battle stations included securing the ventilation to prevent the spread of fires, contamination, or flooding, but smoke from the men’s attempts to burn documents thus hindered their efforts. Crewmen might have weighed the choice of violating the ship’s sealed ventilation in order to open some of the ports or to apprise Bucher of their dilemma but decided against that option. The ship’s incinerator could only burn about 25 pounds of material per hour, and the two hand-fed paper shredders could shred just two reams an hour, a wholly disastrous situation given the time constraints. In addition, the men failed to douse classified material with diesel fuel to facilitate burning sensitive papers. The ship carried enough weighted bags to enable the crew to dump such material overboard, but they failed to do so completely. Some of the men used fire axes, sledges, and chipping hammers to destroy equipment. The NSA intercepted North Korean radio traffic that revealed that the North Koreans saw Pueblo crewmen throwing objects overboard and also burning materials. The men could have thrown more material and equipment overboard through ports, however, without unduly exposing themselves to enemy gunfire.

Vice Adm. Harold G. Bowen Jr., directed a court of inquiry into the attack, which convened at Naval Amphibious Base, Coronado, Calif. (20 January–13 March 1969), and elaborated that many crewmen believed that they should not expose themselves “for any reason regardless of the urgency. This substantially restricted the burning or jettisoning of classified material and equipment. Nevertheless, it was the Court’s opinion that destruction of all classified documents could have been completed in the time available if properly organized personnel below decks had filled and jettisoned all weighted bags while accepting the minimum risk of exposure” topside. The court also contended that “facilities, organization and procedures did not exist to effect the rapid destruction of classified material” on board Pueblo, and that the crew had not been properly trained in destruction procedures.

Bucher ordered the ship to stop at 1334 and the North Koreans ceased firing. The commanding officer checked on the crew’s progress in destroying classified material and equipment, and then rang up one third speed in a wide turn to follow P/N 35. Within a half hour Bucher again stopped the ship to inspect the progress of the emergency destruction, but the enemy opened fire at close range and the rounds slammed into the ship’s laundry and the starboard side just aft of the electronics office, near frame 54 just above the main deck. Twenty-one-year-old FN Duane D. Hodges, USNR, of the ship’s company, who hailed from Creswell, Ore., “rendered invaluable assistance in the face of the intense hostile fire while participating in the unfamiliar task of destroying classified materials,” but the gunfire sliced off most of his right leg and he died by about 1500. Hodges was subsequently awarded the Silver Star posthumously, and Rear Adm. Thomas E. Bass III, Commandant, Thirteenth Naval District, presented the medal to Jesse D. and Stella L. Hodges, the young fireman’s grieving parents. The burst also seriously wounded Sgt. Robert J. Chicca, USMC, RM3 Charles H. Crandell, and FA Steven P. Woelk. HM1 Herman P. Baldridge, the ship’s hospital corpsman, did everything he could for the wounded men and administered first aid, including morphine, epinephine, and oxygen, to casualties in an improvised station in the passageway outside the wardroom.

Lt. (j.g.) Carl F. Schumacher, USNR, the ship’s operations officer, “repeatedly exposed himself to the intense fire while organizing and providing the necessary supervision to ensure the destruction of all classified materials under his purview,” actions for which he afterward received the Silver Star. “Through his inspiring leadership, courage, and dedication in the face of hostile fire, he reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.” Altogether gunfire, fragments, and glass shards wounded Bucher, Harris, Lt. Edward R. Murphy Jr., the executive officer, CT1 Michael T. Barrett, CT2 Peter M. Langenberg, Chicca, SM2 Wendell G. Leach, Crandell, CTSN Steven J. Robin, and Woelk.

Pueblo repeatedly pleaded for help and during one such exchange with Naval Security Group, Kamiseya [Kami Seya], Japan, the group informed the ship that they were attempting to coordinate action for immediate relief. “Sure hope someone does something,” the ship replied forlornly, “We are helpless...” The Americans kept their machine guns covered and did not return fire, and the North Koreans ordered Pueblo to ring “all stop” and attempted to board, and the U.S. ship repeatedly broadcast an SOS distress signal.

Pueblo temporarily avoided the boarders but at about 1420, P/N 604 backed toward her bow with her fenders rigged, and at 1432 the ship sent her final and ominous transmission: “…being boarded at this time…going off the air now and destroying this gear.” Two North Korean junior officers armed with automatic pistols led eight to ten riflemen with fixed bayonets on board on the vessel, and a short while later a colonel led a second boarding party and one of their pilots took the helm.

The North Koreans claimed that they seized Pueblo because she supposedly violated their territorial waters, but the ship’s closest point of approach to land measured just over 15 nautical miles from Ung-Do, an island that marked the nearest land. At 1730 on the 24th, Lt. Gen. Marshall S. Carter, USA, heading the NSA, called Richard M. Helms, Director of Central Intelligence, and informed him that all of the North Korean radar signals that the NSA intercepted indicated that the ship operated “well outside” the 12 nautical mile territorial water limit. “By any reasonable criteria [referring to Pueblo’s position when seized] this placed ship in international waters,” Adm. Ulysses S. G. Sharp Jr., Commander in Chief, Pacific Command, later testified.

The crew’s failure to maneuver Pueblo to sea to escape the attackers -- or barring that alternative in the event that the faster North Korean vessels had continued to attack and blocked their escape -- to scuttle the ship or to properly destroy cryptologic equipment, radar and electronic systems, document holdings, and manuals, likely enabled the boarders to seize a treasure trove of such materials. Vice Adm. Hyland observed dismally in his endorsement of the court of inquiry’s findings that the “compromise of sensitive information can very well be turned against the United States and ultimately cause the loss of untold lives in other confrontations. This is the tragedy of PUEBLO.” The ship did not strike her colors but the boarders took Pueblo into Wŏnsan, and moored her to a dock ten miles northwest of the city at about 2030. The North Koreans hauled down the colors, bound and blindfolded the Americans, and led them through a crowd of people who spit and kicked at them, and treated the prisoners with derision. Buses and a train took the crew to their initial place of detention, a prison compound in Pyŏngyang that the prisoners dubbed “The Barn.”

The nearest U.S. ships operated too far away to effectively intervene in time to prevent the North Koreans from taking Pueblo into port. Aircraft carriers and their task groups deployed to the Vietnam War in cycles and, on 3 January 1968, attack aircraft carrier Enterprise (CVAN-65), Capt. Kent L. Lee in command, set out from Naval Air Station (NAS) Alameda, Calif., to take part in the fighting in Southeast Asia. Rear Adm. Horace H. Epes Jr., Commander, Carrier Division 1, broke his flag in the ship, and she embarked Attack Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 9. A tropical depression slammed into Enterprise and her escorts, guided missile frigates Truxtun (DLGN-35), Capt. David D. Work, and Halsey (DLG-23), Capt. Vincent L. Murtha, as they approached Japanese waters. Towering waves battered the ships and Lee slowed the carrier to steerageway in what he recalled as the worst weather he had experienced at sea since World War II. Enterprise and Truxtun accomplished repairs and upkeep at Sasebo and returned to sea on the 23rd.

The carrier and her consort formed Task Group (TG) 77.5 and steamed southwesterly courses at 27 knots in the East China Sea near 31º17'N, 129º8'E, about 550 nautical miles south of Wŏnsan, when, at 1430 on 23 January 1968, she received a message concerning the crisis. The cumbersome communication process delayed the alert message and word only reached Enterprise more than an hour after the North Koreans opened fire on Pueblo. The attack surprised Capt. Lee because he had not been briefed on the environmental research vessel’s mission.

At 1506 Vice Adm. Bringle ordered Enterprise and Truxtun to come about and make “best speed” for the scene. Forty-four minutes later the ships turned to northerly courses and proceeded toward a position at 32º30'N, 127º30'E. Two McDonnell Douglas F-4B Phantom IIs on board Enterprise already stood ready to launch within five minutes to fly a combat air patrol to protect the ships, followed by a second pair. The Phantom IIs carried only AIM-9 Sidewinder short range air-to-air missiles and AIM-7 Sparrow medium range missiles, however, and although the jets might have escorted other aircraft or flown widely ineffective missile runs on North Korean vessels, they would have been of little use on a strike against ships or an airfield without being rearmed with bombs. “The Enterprise’s planes on a trip like that,” Sharp elaborated, “would be on deck…but not loaded…”

Enterprise received orders en route to make ready a photographic reconnaissance flight of the Wŏnsan area and to organize a raid. The carrier did not have mission folders for North Korean targets because she was en route to Vietnamese waters, but Lee estimated that upon receiving a tasking order he might have been able to send 20 strike jets into the air within an hour and a half, and that within an hour and a half after the aircraft launched they would have reached their targets in the Wŏnsan area. Enterprise might also have sent up a limited strike by about 1610, and by 1710 those jets would flown over the North Korean port. Launching a raid during the afternoon or first dog watches that day left little room for error because the sun set at Wŏnsan at 1737 and by 1806 total darkness blanketed the area.

Hyland recalled the 23rd as a “gray, misty winter day.” Clouds covered the Wŏnsan area at 6,000 feet with occasional overcast and scattered clouds down to 3,000. The strike jets would have flown a long range mission and arrived after the North Koreans seized Pueblo, and nearly a half hour after they brought her into the harbor. They had to break through the wintry weather to differentiate Pueblo from other ships in the harbor, all the while evading MiGs and enduring fire from the ground. Aircrew who bailed out faced captivity or survival in the cold water measured in minutes. The survivors might have come about following the raid and landed on airfields in South Korea before they consumed their fuel, but launching under such circumstances presented a grim prospect. Briefings turned serious without the banter that punctuated peacetime training.

“I have a track chart, supplied me from the Enterprise,” Rear Adm. Epes later responded to Congressional queries. “We were transients in the area, as you know…our mission was to proceed south to the Philippines area…to engage in several days of refresher air operations to prepare for action in the Gulf of Tonkin as we had not flown since before Christmas. Many of our aircraft were in repair. We had encountered a severe storm in crossing the Pacific which had caused corrosion and water damage on a number of them; and as you see from the figures General Wheeler [Gen. Earle G. Wheeler, USA, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] gave, the number of aircraft was considerably below what you would normally expect to have available.”

Wheeler revealed that Enterprise counted up to 59 strike aircraft on board, numbering 24 F-4Bs of Fighter Squadrons (VFs) 92 and 96, 23 Douglas A-4E and A-4F Skyhawks of Attack Squadrons (VAs) 56 and 113, and 12 Grumman A-6A Intruders of VA-35. Because of storm damage and maintenance issues, however, the operational strike force numbered only 35 jets, consisting of ten Phantom IIs, 19 Skyhawks, and six Intruders. Intelligence analysts believed that the North Koreans deployed an estimated 74 Frescos and MiG-15 Fagots of the 26th and 58th Regiments from an airfield near Wŏnsan, and another 37 of the 58th Regiment at So’ndo’k [Sondok] about 40 miles to the north. Furthermore, they deployed the more advanced MiG-21 Fishbeds at other fields, as well as Ilyushin Il-28 Beagles, obsolete light bombers that were nonetheless capable of attacking ships. They often dispersed their aircraft into caves, revetments, and hardened concrete bunkers. Fourteen antiaircraft sites, each with six guns, and two SA-2 Guideline (SA-75N Desna) surface-to-air- missile sites also girded the Wŏnsan area. “We knew, of course,” Sharp noted, “they [the North Koreans] had a couple of MiG’s up, and — well, we all just assumed that at least the aircraft in Wŏnsan were going to be at maximum alert. They almost assuredly were...” The NSA intercepted message traffic that indicated that the North Koreans ordered a “combat emergency call” and alerted their aircraft and antiaircraft batteries in the Wŏnsan area, as well as at their naval station at Namp’o, southwest of Pyŏngyang on the west coast, and successively extended their patrols about 30 miles to sea from Wŏnsan. Analysts believed that they operated defensively and did not identify signs of preparations to attack American troops in the region or the South Koreans, but the carrier air wing’s planners reported that the enemy could attain “vast numerical superiority” and intended to compensate through surprise, speed, and fighter support for the strike group.

Jets could have attacked North Korean vessels or aircraft but in all likelihood would not have been able to affect the seizure. “I’m quite sure that after they [the North Koreans] boarded her [Pueblo]…” Vice Adm. Hyland surmised, “a couple of airplanes flying around overhead weren’t going to make them decide to disembark…” Assistant Chief Counsel Frank M. Slatinshek pressed Epes during Congressional hearings: “Well, it had been boarded by the North Koreans…Could your aircraft have attacked without getting authority from someone superior to you?” The admiral responded tellingly: “I think that would be a matter of judgment at the time. I certainly wouldn’t intend that a pilot attack a ship that had 82 U.S. sailors aboard, and was already proceeding into an enemy harbor escorted by enemy armed vessels.” The Americans opted against attempting to launch a strike that day, and just after midnight Epes informed Bringle that Enterprise could launch aircraft at dawn.

United States planners initially considered transferring Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) from Vietnamese waters to reinforce Enterprise, but in the interim the only viable option for strikes comprised additional land-based aircraft. Marine Aircraft Group 15 theoretically counted 17 F-4Bs of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 542 and 22 A-4Cs of Marine Attack Squadron 223 at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni in Japan. Only four Phantom IIs and four Skyhawks, however, had carried out refresher training in air-to-ground delivery. The marines did not receive word of the incident until the mid watch at 0115, and then began to reposition some Skyhawks from NAS Cubi Point in the Philippines. The Fifth Air Force counted up to 18 Republic F-105s of the 18th Tactical Fighter Wing at Kadena AB in Okinawa. The Thunderchiefs did not possess all-weather weapon capabilities, however, and probably also would not have reached the Wŏnsan area until dusk. Lt. Gen. McKee ordered a dozen Thunderchiefs to Osan AB in South Korea, which were to launch incrementally as their maintainers readied them, the first increment consisting of the initial six available jets. The first two of only four pairs of the fighter-bombers did not begin to arrive at Osan until 1735, however, and then received directions to be in position by “first light.” The Air Force had another seven attack aircraft in South Korea and 16 more in Japan, the latter consisting of 11 Phantom IIs at Misawa Air Force Base (AFB) and five Thunderchiefs at Yokota AFB. McKee placed fighters and photo aircraft in maximum alert, but the estimated times to targets in the Wŏnsan area reached up to four hours ten minutes from Okinawa by staging through Osan, and four hours 55 minutes from Japan.

The North Koreans accused Pueblo and her men of committing “criminal aggressive acts,” assembled Bucher and his officers shortly after they reached the first detention site, and questioned them concerning the ship’s operations. The commanding officer provided only his name, rank, and duties on board Pueblo, and the other officers followed his example. The Americans did so knowing that the boarders searched the ship and discovered the crew’s service jackets, but for this response, the general commanding the interrogators told each man who so answered that he would be shot at sundown. Bucher’s defiance infuriated the interrogators and they alternatively threatened and beat him, but the commanding officer refused to sign a typewritten confession of espionage activity. The North Koreans then took Bucher to view an alleged South Korean spy that they had severely tortured and mutilated, but he still refused to cooperate. Their senior colonel then threatened to shoot Pueblo’s entire crew one-by-one, starting with the youngest man, and early on the morning of 25 January Bucher signed the confession. Some of the other prisoners also underwent severe beatings and torture and signed confessions about Pueblo’s alleged intrusion into North Korean territorial waters.

The Americans’ captors possessed their personnel records and many records of the ship, which made it virtually impossible for the men to strictly adhere to the Code of Conduct. “It would be unreasonable to expect the members of the crew,” the court determined, “to have withstood prolonged mistreatment to protect information which was obviously known by the North Koreans.” The torturers robbed the prisoners of their watches and other valuables, and at times punched and kicked them in their faces or groins, and forced some to squat with an inch square board behind their knees with a chair held above their heads. If any of the crewmen waivered or fell the torturers beat or kicked them, and some of the prisoners lost consciousness during the heinous treatment.

Sgt. Robert J. Hammond, USMC, subsequently received the Navy Cross for his “extraordinary heroism” Hammond’s resistance during his imprisonment infuriated the North Koreans and they singled him out for “more frequent and far more severe brutalities than were administered to the other prisoners.” At one point the interrogators intensified their efforts to break the prisoners’ will and spirit, and when the marine realized that the torture might maim or kill some of the prisoners, he “willingly attempted to sacrifice his own life in order that his shipmates might be spared further torture.” Schumacher, Ens. Timothy Harris, Langenberg, BM2 Ronald L. Berens, SM2 Wendell G. Leach, and Chicca each received the Bronze Star for “steadfastly” defying their captors despite being “subjected to extreme forms of physical and mental cruelties.”

The North Koreans grew frustrated by the men’s uncooperative behavior and “increased the tempo and severity of their ruthless treatment,” but the six prisoners’ “courageous stand[s] served to inspire” their fellows and strengthen their will to resist. Lt. Murphy stoically defied his captors. Interrogators beat QM1 Law bloody with a board, but the quartermaster refused to talk and deflected his torturer’s anger from his shipmates onto himself. Crewmen acclaimed Law’s leadership and noted that he proved instrumental in upholding the chain of command. The North Koreans recurrently ordered the men to write letters to American politicians and the media condemning Pueblo and her operations, but when CT3 Earl M. Kisler refused to write to the press the guards beat Kisler so badly that his fellow crewmen could not recognize him for days afterward. In addition, the Navy awarded its Distinguished Civilian Service Medal to Dunnie R. Tuck Jr., the ship’s senior oceanographer, and the Superior Civilian Service Medal to Harry Iredale III, the junior oceanographer, for their “meritorious service…[and] unwavering devotion.”

The North Koreans initially separated Bucher from his crew and crammed the enlisted men together three or four to a room. On 4 March 1968 their captors transferred the prisoners to a second compound on the outskirts of Pyŏngyang that the men scathingly named “The Farm.” The officers then usually had their own rooms and enlisted men slept eight to a compartment. Their daily regimen included an hour of self-examination to afford the men the opportunity to correct their “wrong-living and wrong-thinking.” The North Koreans prevented representatives of the Red Cross and other international organizations from visiting the prisoners. The captors fed the captives poor food that lacked vitamin and nutritional content, normally rice, bits of fish, turnip soup, and bread and butter that comprised barely a 500 calorie diet.

The North Koreans served the food in unsanitary buckets, and the Americans suffered from multiple illnesses including diarrhea, pneumonia, scurvy, hepatitis, and other afflictions associated with or exascerbated by their malnutrition. Bucher lost nearly 100 pounds. They forbade Baldridge from treating the victims, and provided only minimal medical care during the first months of captivity. The guards placed the seriously wounded men in a single room, where they languished in pain for four days until the North Koreans performed an unsanitary surgery on Woelk, whose wounds then became infected and he suffered for nine more days before he was treated. Chicca did not receive surgery for nearly a month. The court afterward singled out SN Dale E. Rigby for his “youthful compassion and devoted attention in his care of three wounded roommates,” Chicca, Crandell, and Woelk, and added that Rigby most likely saved Woelk’s life.

Meanwhile ships rushed to the crisis and at 1921 on 23 January 1968, Sharp ordered Bringle to dispatch Higbee (DD-806) to the scene. A second destroyer was to rendezvous with Higbee off Wŏnsan “as soon as Enterprise escort assets permit,” and overnight (23–24 January) Enterprise and Truxtun chartered easterly courses into the western passage of the Strait of Tsushima at an average speed of 15 knots. At 0138 on the 24th, Sharp directed all of the ships in the area to operate south of 36ºN. By midday the command changed the orders and directed all forces to operate outside of an area within 80 nautical miles of the North Korean coast south of a line extending east from the DMZ. Bringle diverted Enterprise and Truxtun to make for a position in the Korea Strait near 34ºN, 128º42’E. “Can’t the Enterprise take care of the situation for a few days?” President Lyndon B. Johnson asked members of his cabinet during a meeting on the 25th. “We do need more air power in the area,” Secretary of Defense McNamara recommended, “if we are attacked.” Despite the secretary’s justifiable misgivings concerning tactical aircraft, Lockheed P-2 Neptunes and P-3 Orions flew 50 barrier patrols over the Sea of Japan through the end of January and another 238 in February.

Halsey and four destroyers were to close Enterprise: Collett (DD-730) was to sail from her position at sea about 120 miles south of Yokosuka; Higbee from Sasebo; O’Bannon (DD-450) from upkeep at Yokosuka; and Ozbourn (DD-846) after she refueled at Buckner Bay in Okinawa. The Navy diverted TG 70.0, formed around antisubmarine warfare support aircraft carrier Yorktown (CVS-10), with Antisubmarine Carrier Air Group (CVSG) 55 embarked, and six destroyers, and TG 77.7, built upon Ranger (CVA-61) with CVW-2 and three destroyers, toward the region, and extended the deployment of Oriskany (CVA-34) and CVW-16 in Vietnamese waters. Enterprise and Ranger rendezvoused off the eastern coast of the Korean peninsula on the last day of the month. A number of submarines also deployed to the crisis, including Ronquil (SS-396), which had participated in filming the motion picture Ice Station Zebra in August.

Bitter winter weather plagued the ships and their men throughout the confrontation. Slightly modified continental polar air dominated the weather over the Sea of Japan into February. Rain and snow showers repeatedly pounded the region during the mornings, followed by partly cloudy skies into the afternoons and clouds overnight. Snow fell onto Enterprise’s flight deck and slush sometimes gathered to a thickness of a half inch, and the wind chill repeatedly fell below freezing.

At times during the crisis, U.S. commanders reviewed contingency plans that ranged from a show of force off Wŏnsan, to recapturing Pueblo, or to seizing a North Korean vessel as a counter. The Navy’s principal plan, Operation Formation Star, comprised three options: Two carriers were to launch raids against a single target area, most likely Wŏnsan; aircraft were to fly from South Korean and Okinawan fields to attack two or more target areas; or carrier and land-based aircraft would launch a combined raid. Additional planning included mining North Korean harbors, and Intruders of VA-35 from Enterprise were to fly 17 sorties on a single night to lay 83 mines in Wŏnsan, with an option to ‘reseed’ if necessary. Planners later expanded the strategy to joint air and naval minelaying to close the nine significant ports. The Americans also considered imposing sanctions or blockading the North Koreans, but debated the effectiveness of such measures because the latter carried out most of their trade overland.

In addition to the North Koreans, Soviet aircraft, ships, and submarines monitored the Americans, and their operations sometimes escalated into tense encounters. A Riga-class frigate illuminated Banner with a searchlight from barely 450 yards on the evening of the 29th, but after several tense minutes backed-off and trailed the U.S. ship from 5,000 yards. The following day 10,000 ton Soviet merchantman Kapitan Vislobokov disregarded the right of way of Rowan (DD-782), crossed illegally and collided with the destroyer about 100 miles south of the South Korean port of Pohang. The impact tore a three foot hole in Rowan’s port bow above the waterline and dented the merchantman’s stern but no casualties ensued. At one point Soviet spy trawler Gidrolog closed to barely 900 yards of Yorktown and become a burdened ship before coming about. Bringle observed that Soviet vessels harassed U.S. ships at least 14 times during the initial phase of the crisis (23 January–21 February).

Early in February 1968, Bringle broke his flag in command of TG 70.1 in guided missile light cruiser Providence (CLG-6), and divided the available ships into four forces: TG 70.6, a strike group formed around Enterprise; TG 77.7, a second strike group based upon Ranger; TG 70.0, an antisubmarine group centered on Yorktown; and a surface action group comprising guided missile cruiser Chicago (CG-11) and Dewey (DLG-14). Kearsarge (CVS-33), with CVSG-53 embarked, relieved Yorktown on 1 March, and Yorktown made for Vietnamese waters. Four days later Coral Sea (CVA-43) relieved Ranger. The Americans gradually reduced their high paced tempo of operations as diplomats de-fused the crisis, though deployments to the region continued. They ended the standing carrier presence at midnight on the 21st and released Coral Sea and Kearsarge, though Hancock (CVA-19) sailed in the Sea of Japan in early December.

Into early February the Americans also surged more than 300 aircraft into the theater to offset growing North Korean air power. In addition, the Navy mobilized reservists including 568 officers and men involuntarily recalled to active duty to man six Navy Air Reserve squadrons: VF-661, originally from Naval Air Facility Washington, D.C., which flew Vought F-8C and F-8H Crusaders out of NAS Cecil Field, Fla.; VF-703, NAS Dallas, Texas, F-8Js, NAS Miramar, Calif.; VF-931 from Willow Grove, Pa., F-8Cs and F-8Hs, Cecil Field; VA-776, NAS Los Alamitos, Calif., A-4Bs and A-4Fs, NAS Lemoore, Calif.; VA-831, New York, A-4Bs and A-4Cs, Cecil Field; and VA-873, NAS Alameda; A-4Bs, and remained at Alameda. Additional reservists on their annual training duty helped fleet tactical support squadrons (VRs) to fly Douglas C-118B Liftmasters that shuttled cargo via NAS Barbers Point, Hi., to support these deployments across the western Pacific.

The crisis generated heated debate about the potential vulnerabilities of intelligence ships. “The Soviets recognize the value of the surface ship in this role,” Moorer stated before the subcommittee on 4 March 1969, “and, in fact, employ about 40 unarmed intelligence collection ships, which we call AGIs, that operate freely, far from home waters and well beyond the protective reach of other Soviet forces.” The members concurred and reported that the “effort which the Soviets put into this peripheral intelligence collection points out its usefulness to them. It is of no less importance to the United States.”

The 82 survivors, meanwhile, endured 11 months of cruel captivity. Their jailers repeatedly stymied U.S. negotiators, threatened to place the prisoners on trial, and demanded what the Americans referred to as the “Three As”: for the U.S. to admit that Pueblo had entered their territorial waters; to apologize; and to assure that it would not happen in the future. “The fundamental issue at Panmunjom,” Acting Secretary of State Nicholas deB. Katzenbach wrote in an action memorandum to President Johnson that autumn, “has been that the North Koreans have insisted on our signing an admission of espionage and intrusion into their territorial waters, apologies for both, and a promise of no further intrusion.” The Americans said that they would not tolerate a trial of the prisoners, and the crew finally returned to freedom just in time for the holidays when Maj. Gen. Gilbert H. Woodward, USA, who represented the Americans, signed the “Three As” agreement on 22 December 1968. The North Koreans thus zealously broadcast that Pueblo had entered their territorial waters, but the Americans rejected the accusation. The men walked across a bridge at Panmunjom in 15 second intervals on the 23rd, an agonizing walk for some who feared that the North Koreans would attempt a last minute betrayal and keep them in captivity. “We crossed that bridge at Panmunjom,” Murphy recalled, “battered, weary, a bit emaciated — but alive.”

The North Koreans denied that they had mistreated the prisoners, but the gaunt features of the men upon their release clearly revealed their suffering to the world. In addition to their other awards and citations, all 83 men eventually received the Purple Heart. Hodges received his posthumously, the wounded men for the wounds they incurred during the battle, and all 82 prisoners for the torture and beatings they underwent during their imprisonment. The Navy initially refused to authorize the survivors their Prisoner of War Medals, and only awarded them the medals during ceremonies at San Diego on 5 May 1990. All of the men received the National Defense Service Medal. In addition, a number of them received the Navy Commendation Medal and/or the Navy Achievement Medal, their citation for the former noting that they withstood “the continual harassments of beatings, threats, personal indignities, and malicious propaganda,” and successfully resisting “all attempts” by the North Koreans to use them “in causes detrimental to the United States.”

The North Koreans restricted the prisoners from receiving global news broadcasts and fed them party line propaganda and deceptive information, so that many of the returnees expressed surprise to learn about the year’s events. McClintock asked a young yeoman about the news and the sailor responded about the Apollo 11 mission. “What? Men on the moon?” McClintock asked, incredulous. The Army’s doctors and nurses of the 121st Evacuation Hospital examined the men, and on the 24th the survivors held a memorial service for Fireman Hodges at the hospital’s chapel.

Two USAF Lockheed C-141s then flew them to reunions with their families in the United States. The Starlifters refueled at NAS Midway Island, where Vice Adm. Hyland greeted the men and the naval air station staff treated them to a welcome meal of burgers and French fries, and they continued on to NAS Miramar, Calif. Governor and Mrs. Ronald W. and Nancy D. Reagan, Senator Margaret Chase Smith, Navy representatives, many of the crewmen’s loved ones, and a number of journalists greeted the men as they returned home. “City Proudly Hosts Pueblo Crew” The San Diego Union proclaimed on Christmas Eve, and observed that “We are proud to represent the entire nation as the host for these gallant men. There could be no better Christmas present.”

Navy doctors performed psychiatric evaluations on the returned prisoners 48 to 72 hours after their release. “Slightly more than half of the crew,” Capt. Raymond C. Spaulding, MC, of the Environmental Stress Branch, Center for Prisoner of War Studies Division, Naval Health Research Center at San Diego, reported, “admitted to experiencing significant anxiety or depression during captivity. A group of men defined as coping with the stress well was compared to a group who tolerated it poorly. Those who did well tended to use a variety of ego-defense mechanisms, particularly faith, reality testing, denial, rationalization, and humor. Men in the group defined as handling the stress poorly were more limited in the number of ego-defense mechanisms utilized.”

The ego-defense mechanisms the men developed ran a wide range of creative alternatives. The court noted that Bucher “upheld morale in a superior manner” and maintained the command structure. He adamantly demanded that the North Koreans keep the crew together, provide them medical attention and exercise, and halt the beatings and treat them in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Bucher used puns, improvised hand signals, and feigned ignorance of orders to harass and deceive the enemy. The prisoners did not learn the names of their guards and consequently assigned humorous and derisive names to them. They often misused English and Korean and carried on a continuous word harassment campaign against their captors. Some of the Americans participated in a “Movie Hour” at night, whereby one man would endeavor to relate a film he had seen, and others would piece in details. Over time, they grew increasingly proficient at reconstructing motion pictures from their memories. Crewmen developed word challenges, math problems, music compositions, crossword puzzles, construction plans, calendars, and language and math textbooks as creative alternatives to their imprisonment.

The horrific experience deepened the faith of some of the Christians and Jews, and in particular, the 23rd Psalm became a source of solace for many. A number of the crewmen who had hitherto disregarded religion also turned to God to pull them through their travails. The North Koreans forbade worship services and singled out men of faith for abuse and ridicule. They witnessed a sailor saying grace over his meal and called him out of the mess hall, instructing him that “This is a mess hall, not a church. You can’t pray here.” Another man constructed a wooden cross, but the guards kicked it about and finally removed the cross. Their captors’ threats sometimes sounded farcical, and they told them that “The Russians shot God down with a rocket.”

The court of inquiry recommended that Bucher be brought to trial by a general court-martial for five alleged offenses: permitting the ship “to be searched while he had the power to resist”; failing to take “immediate and aggressive protective measures” when the North Koreans attacked Pueblo; complying with the North Koreans’ orders to follow them into port; negligently failing to complete destroying classified material, which the boarders seized; and negligently failing to ensure, before the ship set out for her patrol, that the crew was “properly organized, stationed, and trained” to destroy such material.

The members of the court recommended that Lt. Murphy “be given nonjudicial punishment in the form of a letter of admonition for alleged dereliction in the performance of his duties” as the executive officer, in particular, that he also failed to lead the crew in destroying classified material when the North Koreans seized Pueblo. The court furthermore proposed that Rear Adm. Johnson “receive nonjudicial punishment in the form of a letter of reprimand”, because he failed to plan properly for effective emergency support forces for contingencies “such as occurred.” In addition, the court recommended that Capt. Everett B. Gladding, Director, Naval Security Group Pacific, also receive a letter of reprimand because he failed “to develop procedures to ensure the readiness” of Pueblo’s research detachment, and “to coordinate other services and agencies to provide intelligence support” to the ship.

The court’s “completely objective approach,” Secretary of the Navy John H. Chaffee announced on 6 May 1969, “was clearly reflected in its full presentation of factors which would have mitigating effect with respect to the offenses alleged. Note was taken of such matters as the recent change in policy which resulted in the last-minute installation of armament aboard [sic] PUEBLO; the limitations and deficiencies of that armament installation and of PUEBLO’s other defensive capabilities; the emphasis placed by superior commanders upon the importance of restraint and nonprovocation under harassment; the limitations and deficiencies of PUEBLO’s facilities for emergency destruction of classified materials, and of the Navy’s planning therefor; the absence of centralized control of the amount of classified materials required to be carried by intelligence-collection ships; the failure of other responsible authorities to provide proper support; and the 160 years of precedent which was shattered when PUEBLO was seized by an act of piracy on the high seas in clear violation of international law.”

Vice Adm. Hyland, as the convening authority, declined to accept the court’s recommendations that Bucher and Lt. Stephen Harris be brought to trial by a general court-martial. The admiral proposed instead to institute formal procedures with a view to issuing a nonjudicial letter of reprimand to both of the officers. Hyland concurred with the court concerning Murphy’s letter of admonition, and the reprimand to Johnson — though only for the admiral’s alleged dereliction of failing to verify Pueblo’s capability to rapidly destroy classified material. Hyland disagreed with issuing a letter of reprimand to Gladding. Moorer concurred with Hyland’s recommendations.

“I have decided,” Secretary Chaffee announced on the 6th of May, “that no disciplinary action will be taken against any of the personnel involved...” Chaffee noted that he did not make a “judgment regarding the guilt or innocence of any of the officers of the offenses alleged against them”, but decided against any “further legal proceedings” to Bucher, Murphy, and Harris. “In reviewing the Court’s recommendations…” Chaffee added, “it is my opinion that -- even assuming that further proceedings were had, and even going so far as to assume that a judgment of guilt were to be reached -- they have suffered enough [author’s italics] and further punishment would not be justified. These officers were illegally imprisoned by the North Koreans for eleven months. During that time, their food and living conditions were marginal. They suffered extensively from physical abuse and torturous treatment. Their captors refused to accord them even the minimal humane treatment required under international law. When they were released from their captive status, each showed great loss of weight and other marks of cruel treatment.” The secretary also determined not to punish Johnson or Gladding and their “failure to anticipate the emergency that subsequently developed. This basic, general accusation, however, could be leveled in various degrees at responsible superior authorities in the chain of command and control and in the collateral support structure.”

Chaffee summarized his view concerning Pueblo’s “lonely confrontation by unanticipatedly bold and hostile forces” as stemming largely from “the sudden collapse of a premise which had been assumed at every level of responsibility and upon which every other aspect of the mission had been based -- freedom of the high seas. At that particular point in history, the common confidence in the historic inviolability of a sovereign ship on the high seas in peacetime was shown to have been misplaced. The consequences must in fairness be borne by all, rather than by one or two individuals whom circumstances had placed closer to the crucial event.”

Moorer concurred with Chaffee and during his (earlier) testimony emphasized that Pueblo “was operating in international waters. Her seizure by the North Koreans was an act of piracy in direct violation of international law. From all reports, the treatment accorded her crew while in confinement was brutal and inhumane. Measured by any yardstick, this seizure and retention of a United States ship -- which is a sovereign part of the United States -- and the brutal treatment of American citizens represents a gross violation of the accepted standards of international conduct and of human decency.”

On 14 April 1969 as the subcommittee continued to investigate the seizure of the ship, North Korean MiGs shot down Deep Sea 129, an unarmed Lockheed EC-121M (BuNo. 135749) of Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron (VQ) 1, while the Warning Star flew a routine reconnaissance patrol in international airspace over the Sea of Japan, near 41º12’N, 131º48’E, from NAS Atsugi, Japan, killing all 31 crewmen. The subcommittee thereupon expanded its investigation to include Deep Sea 129’s loss, and held both open and closed sessions in which a number of men testified including Helms, Carter, Wheeler, Moorer, Sharp, Johnson, Epes, and McKee.

The members unanimously agreed that in the wake of the two incidents there existed “serious deficiencies in the organizational and administrative military command structure of the Department of the Navy and the Department of Defense. If nothing else, the inquiry reveals the existence of a vast and complex military structure capable of acquiring almost infinite amounts of information but with a demonstrated inability, in these two instances, to relay this information in a timely and comprehensible fashion to those charged with the responsibility for making decisions.” The members concluded that the “vastness of the military structure, with its complex division into multiple layers of command, and the failure of responsible authorities at the seat of government to either delegate responsibility or in the alternative provide clear and unequivocal guidelines governing policy in emergency situations,” prevented that structure from functioning smoothly and responding rapidly and efficiently to crises. The members also insightfully summarized the U.S. response to both incidents as “absent or sluggish.”

The Navy’s court of inquiry also examined the available operational evidence from the incident, and recommended that future environmental research ship (AGER) operations be premised upon two key points: “assured readiness” and the ability to defend the ships (self-defense and/or external support). Deploying Pueblo in “international waters off the territory of North Korea,” Hyland endorsed the court’s findings, “without friendly military assistance readily available, was a mistake. An assessment of minimal risk was made and approved at every level in the chain of command, and all echelons, including CINCPAC [Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet], erred in underestimating the risk.” He added that such ships had operated off “communist dominated territories for a considerable time without seizure,” and that “a false sense of security based on the international law of freedom of the seas prevailed throughout all echelons of command.”

The court noted that each command involved in the operations normally assessed the risk for the missions by considering the “political climate in the area,” possible hostile reaction, the value of the mission, and the support forces available. The inadequacy of the available forces to protect Pueblo concerned the court, and the members examined the existing instruction, 003120.24A of 28 February 1966, which set out such ship operations. Forces that were to support Pueblo included alert destroyers steaming up to several hours away from the area of operations, aircraft from carriers available within one to four hours, or aircraft flying from ashore. Commander, Naval Forces Japan, was to inform the Seventh Fleet, Fleet Air Wing 6, and the Fifth Air Force about Pueblo’s movements, a practice that was to have facilitated the use of “on call” reaction forces. Rear Adm. Johnson’s 16 December 1967 message to Hyland proposing the ship’s patrol, and the NSA’s similar message on the 29th concerning the “minimal” threat to Pueblo, both underestimated the possible severity of the North Koreans’ reaction. In addition, Capt. Dwyer did not recommend alert air support for the ship because he did not consider the risk sufficient to warrant the reinforcement. Multiple errors compounded the delays in dispatching air support, and at the time of the incident no destroyers steamed within range to help Pueblo. The subcommittee noted the “absence of any requirement that commands proposing and originating reconnaissance mission proposals assess the need for possible emergency support.”

Complacency and communication errors existed at manifold levels along the chain of command and contributed to the ship’s loss. The court therefore recommended that the Pacific Fleet modify the instruction to contain a proposal format as to the necessity for emergency support forces. The Pacific Fleet consequently issued 003120.28 on 7 April 1969, which cancelled that instruction, and promulgated Operation Order No. 204-69, which contained a requirement that a mission proposal include “requirements for and availability of supporting forces (direct and standby)”. The court furthermore recommended that the procedures for “risk assessment be reviewed for improvement at all levels of authority.” Senior leaders concurred and issued their revisions in Joint Chiefs of Staff instruction SM-701-68, Pacific Fleet Serial No. 00546 of 23 December 1968, and in 003120.28. The guidance recognized that the risk level varied from mission to mission and could be susceptible to change, and developed four categories of criteria to evaluate the danger, at least one of which was to be assigned to each patrol based on the anticipated reaction and sensitivity.

The possibility of command and control conflicts in the event that other forces again needed to support one of the ships troubled the members of the court, and they recommended that future patrols occur under the operational control of the Seventh Fleet, with Naval Forces Japan having the operational control for logistics support and “readiness determination.” The Pacific Fleet agreed with the logistics support between missions but disagreed with the recommendation for the operational control during patrols. Operation Order No. 204-69 supported that tasking and stated that “general environmental research ships (AGERs) assigned to the Pacific Fleet will operate under the operational control of the responsible area commander except when conducting tactical surveillance in direct support of First Fleet or Seventh Fleet operations, at which time the AGER will chop to the appropriate fleet commander…The primary mission of the AGER is intelligence collection in a given area. The naval area commander’s knowledge of the area and his inherent capability to provide the intelligence support required by the unit, makes it most desirable to have the AGER under his OPCON [operational control] rather than under the Fleet Commander.” The court felt that the revised instructions and orders adequately provided for command and control of any contingency backing for the ships.

The service furthermore introduced additional training concerning the Code of Conduct, the Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape course, first aid training, and greater familiarity with emergency destruction methods of classified material and equipment. The North Korean seizure of Pueblo left Banner as the only such commissioned ship in the Pacific Fleet, and the Navy followed the court’s recommendations and modified Banner at Ship Repair Facility Yokosuka, completing the work on 28 February 1969. The facility installed two single 20 millimeter guns, as well as emergency destruction and scuttling equipment. In addition, her crew received defensive action guidance, including fighting the ship; the men also received scuttling guidance; the Navy established “rigid procedures” to reduce and control classified material; and Naval Forces Japan, the Seventh Fleet, and the Fifth Air Force developed a contingency support plan (2-69).

During Pueblo’s naval service she received the Combat Action Ribbon for her battle on 23 January 1968, and the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (10–23 January 1968).

While at the time of writing Pueblo is carried on the [U.S.] Naval Vessel Register as “Active, In Commission,” the North Koreans retain her as a museum ship at their Pyŏngyang Victorious War Museum.

Mark L. Evans

2 November 2017